Looking for the best art museums to visit in Japan? The Ohara Museum of Art in Kurashiki, Okayama is a must-visit destination for art lovers and cultural travelers. Known as Japan’s first private museum of Western art, it features masterpieces by world-renowned artists such as El Greco, Claude Monet, Henri Matisse, Paul Gauguin, and Auguste Rodin.

—one of the most iconic Western religious paintings, surprisingly housed in Japan.

🖼️ What Makes the Ohara Museum Special?

The museum opened in 1929, founded by Magosaburō Ōhara, a visionary industrialist from Kurashiki. He collaborated closely with Torajiro Kojima, a Western-style painter who traveled across Europe to carefully select authentic artworks to bring back to Japan. Their mission:

“To let the Japanese public experience real Western masterpieces firsthand.”

Thanks to this passion, the Ohara Museum became a pioneer in bringing European art to Japan—decades ahead of its time.

🏛️ More Than Western Art

While its Western art collection is impressive, the museum also showcases:

- Modern Japanese paintings

- Contemporary art

- Ancient Egyptian and Chinese artifacts

This wide range never feels scattered—each piece is thoughtfully curated to highlight its unique beauty.

🆕 New in 2025: The Kojima Torajiro Memorial Hall

In April 2025, the museum expanded to include the Kojima Torajiro Memorial Hall, a dedicated space for exploring the life and works of the Okayama-born artist. It adds a personal and historical dimension to the Ohara Museum experience.

🧭 How to Enjoy Your Visit

Whether you’re strolling through Kurashiki’s Bikan Historical Quarter or planning a deeper cultural tour, the Ohara Museum of Art offers an unforgettable art experience that blends East and West, tradition and modernity.

Torajiro Kojima and Belgium: The Story Behind “Belgian Girl Dressing Kimono”

The Ohara Museum of Art is home not only to Western masterpieces but also to works by Torajiro Kojima, a key figure in the museum’s founding. Among his most iconic paintings is Belgian Girl Dressing Kimono (1911)—a vibrant portrait painted during his time in Belgium. This artwork, now part of the museum’s permanent collection, also marked Torajiro’s first successful entry into the Paris Salon.

Torajirō Kojima, 1911

Oil on canvas, 116 × 89 cm

Collection of the Ohara Museum of Art

The painting features a Belgian girl wearing a traditional Japanese kimono, surrounded by vividly rendered furnishings. The use of bright, luminous colors reflects the influence of Impressionism, which was popular in Europe at the time.

Before his studies abroad, Torajiro had painted in a more realistic and subdued style, as seen in works like Village Watermill (1906). So how did his artistic vision change so dramatically?

Collection of the Ohara Museum of Art

🇧🇪 Discovering Luminism in Belgium

Like many Japanese artists in the early 20th century, Torajiro initially stayed in Paris to study Western painting. However, he soon felt out of place in the city’s fast-paced atmosphere and relocated to Belgium. (Some sources suggest that he didn’t get along with his first mentor, Raphaël Collin, whom he met through Seiki Kuroda.)

image:by JoJan

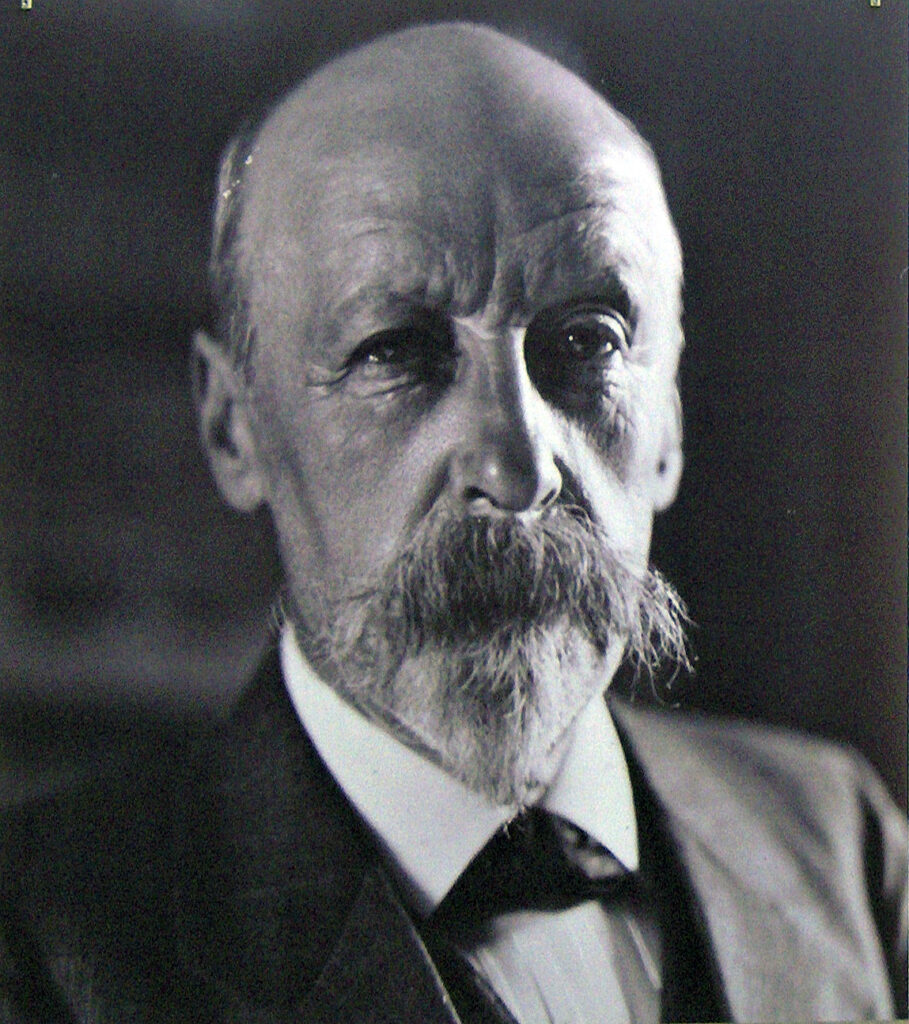

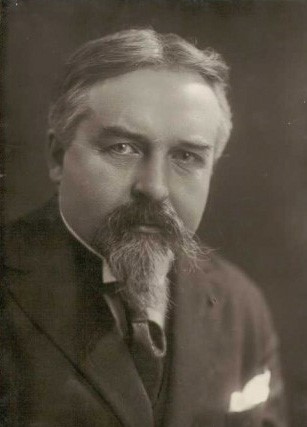

In Belgium, Torajiro encountered Emile Claus (1849–1924), a prominent painter and leader of the Belgian Impressionist movement known as “Luminism.” Claus’s works were known for their radiant light and vivid color palette.

Although Claus had started with a more traditional, realist style rooted in Flemish painting, he later embraced the use of light and color influenced by French Impressionism. However, he didn’t simply copy it—he blended it with strong composition and precise drawing, creating a style that was both modern and grounded in tradition.

Oscar De Vos Gallery Collection

🗣️ “Be Your Own Tuning Fork”

Torajiro became Claus’s student and often visited his home for advice. During one of their conversations, Claus offered this guidance:

“Every painter must express their own individuality.

Source: Torajiro Kojima, edited by Tomoko Matsuoka and Hideto Tokito. Published by Sanyo Shimbun Publishing, May 28, 1999, p. 51. (in Japanese)

I have Flemish blood and must paint as a Flemish artist.

You, as a Japanese, must paint representative works of your people.

Don’t waste time imitating European styles.

A true painting must reflect the artist’s spirit.

Imitation is not truth.”

This advice had a lasting impact on Torajiro. Inspired by Claus’s words, he began to blend Western techniques with his Japanese identity, searching for a personal artistic voice.

That journey led to Belgian Girl Dressing Kimono. When Torajiro showed the completed painting to Claus, his mentor responded:

“Keep this painting nearby and compare it with your future works.

For you, this piece will be like a tuning fork—

something to return to when refining your style.”

Torajiro gained great confidence from this praise. He submitted the painting to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where it was officially accepted—marking a major breakthrough in his career.

🇯🇵 A Crossroads of East and West

After returning to Japan, Torajiro continued painting subjects in traditional clothing, such as kimono or Korean hanbok. His later works became more refined in composition and color, yet they retained the same soft, gentle mood seen in Belgian Girl Dressing Kimono. It’s clear that he carried Claus’s “tuning fork” metaphor with him throughout his artistic journey.

During Torajiro’s time in Belgium, the local art scene was shifting. While Realism remained deeply rooted in Flemish traditions, French Impressionism was starting to gain influence. This cultural blend provided Torajiro with the perfect setting to rethink his own style and artistic roots.

🎨 Torajiro’s Legacy and the Role of Belgian Art

When discussing Western art, people often think of Italy or France. But Torajiro Kojima’s legacy—and the founding of the Ohara Museum of Art—cannot be understood without considering the role of Belgium.

So when you visit the museum, don’t just look at the paintings through a Western lens. Try to see them from a “Japan and Belgium” perspective—you might discover a whole new layer of meaning and beauty.

Other Highlights from the Ohara Collection

El Greco, The Annunciation (1590)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

One of the most iconic works in the Ohara Museum of Art is The Annunciation by El Greco.

This subject comes from a scene in the New Testament, where the Archangel Gabriel appears to the Virgin Mary to announce that she will give birth to Christ. It was a popular theme in European religious art from the Middle Ages through the Renaissance. A famous example is The Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus by Simone Martini, housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

Collection of the Uffizi Gallery, Florence

In contrast to Martini’s version, El Greco’s Annunciation is far more dramatic. The figures are elongated and dynamic, and the space has an almost otherworldly feel. These stylistic traits are typical of Mannerism, an art movement that followed the High Renaissance.

Though El Greco was active in Italy and Spain in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, his style fell out of favor for centuries. It wasn’t until the 20th century, with the rise of Expressionism and a renewed interest in Mannerism, that El Greco’s genius was rediscovered. Torajiro Kojima acquired The Annunciation during this period of renewed attention.

How The Annunciation Came to Japan

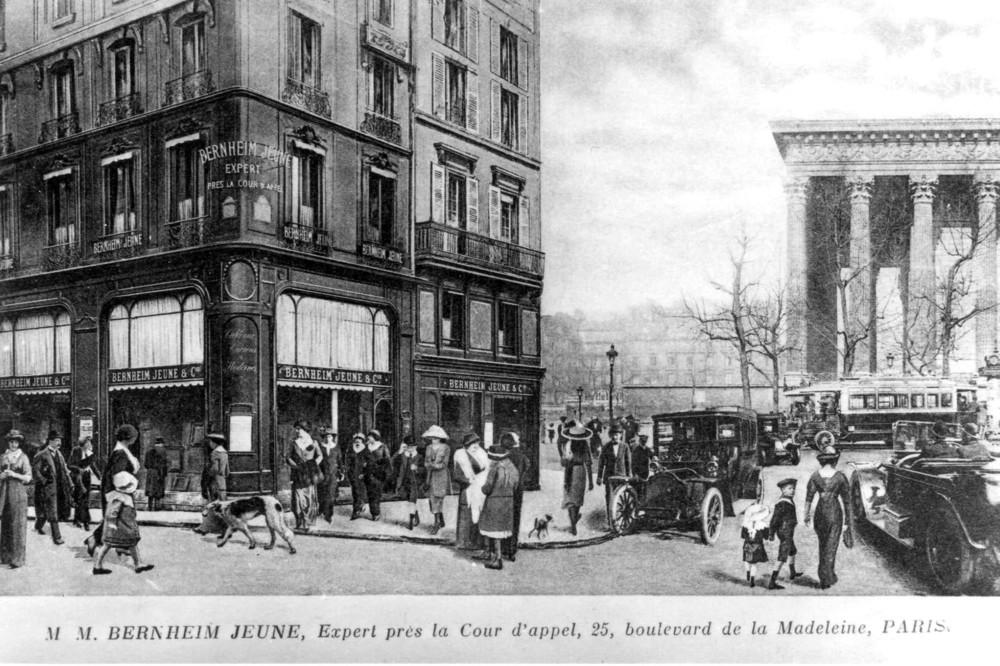

In 1922, during his third trip to Europe, Torajiro discovered The Annunciation for sale at a gallery in France. He was traveling with the full support of Ohara Magosaburō, with the goal of building a new museum collection. Torajiro immediately sent a letter along with a photograph of the painting, asking Ohara to fund the purchase.

The price at the time was an astonishing 150,000 francs (roughly 200 to 300 million yen in today’s currency). Despite the financial instability following World War I, Ohara agreed without hesitation. This decision reflects both Torajiro’s discerning eye and Ohara’s trust in him—as well as their shared vision of bringing great Western art to Japan.

Today, there are only two El Greco paintings in Japan: The Annunciation at the Ohara Museum and Christ on the Cross at the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo.

This is the gallery where Torajiro Kojima purchased El Greco’s The Annunciation. It closed in 2019.

The Purchase and Its Deeper Meaning

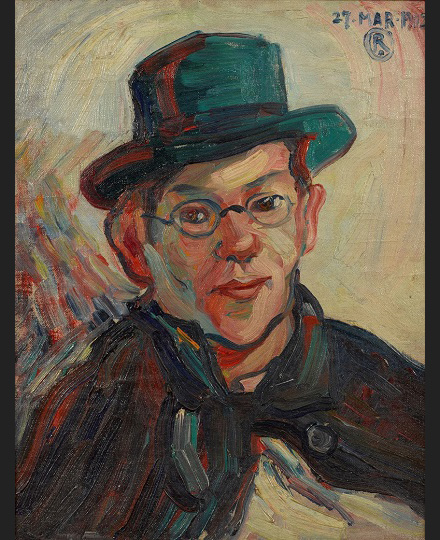

In Japan during the early 20th century, most Western art being introduced was Impressionist or Post-Impressionist. Many young artists simply imitated what was trendy in Europe. Torajiro once criticized this, saying, “When Van Gogh is in fashion, everyone talks about Van Gogh. When Tagore is in fashion, everyone talks about Tagore.” He worried that Japanese artists lacked their own voices and principles.

By adding a 16th-century religious painting like The Annunciation to a collection otherwise centered on modern art, Torajiro may have been trying to show that Western art is more than just surface styles—it has deep historical and spiritual roots. He wanted young artists in Japan to develop their own artistic perspectives rather than chasing fleeting trends.

Collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

Even Ryūsei Kishida, a major figure in modern Japanese art, once experimented with a Van Gogh-inspired style—something Torajiro viewed with concern.

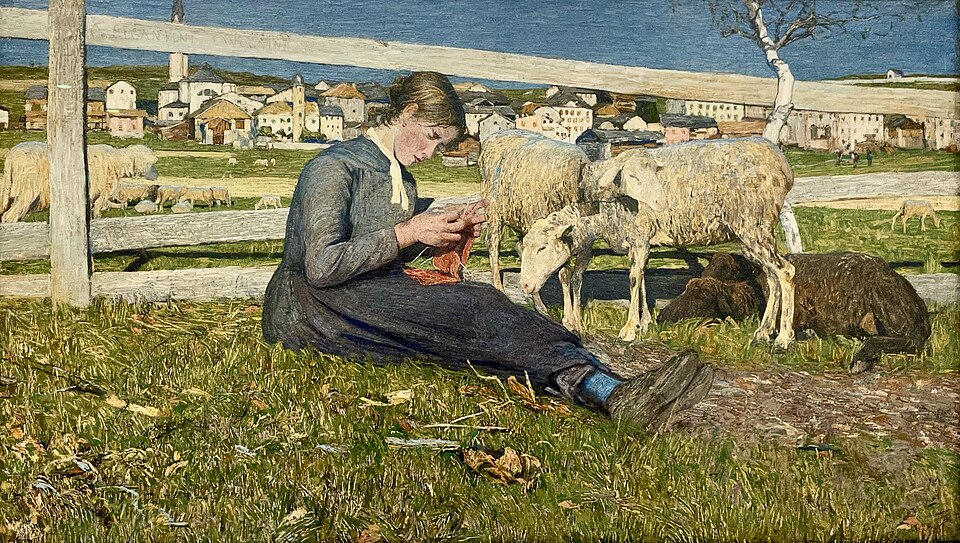

Giovanni Segantini, Midday in the Alps (1892)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

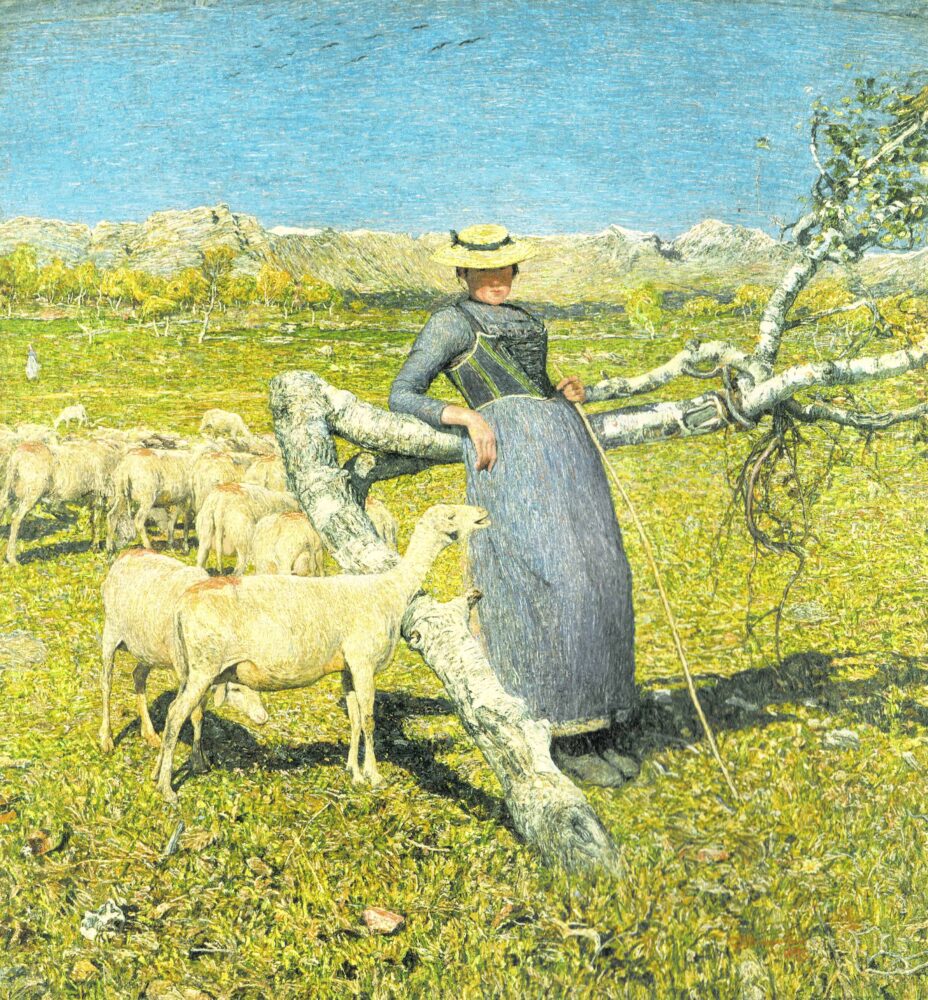

Giovanni Segantini was an Italian painter best known for his radiant Alpine landscapes. Midday in the Alps is one of his most iconic works—and like El Greco’s Annunciation, it was acquired by Torajiro Kojima during his third trip to Europe. Upon purchasing the painting, Torajiro noted, “Segantini’s painting was worth the struggle. It was a good acquisition.”

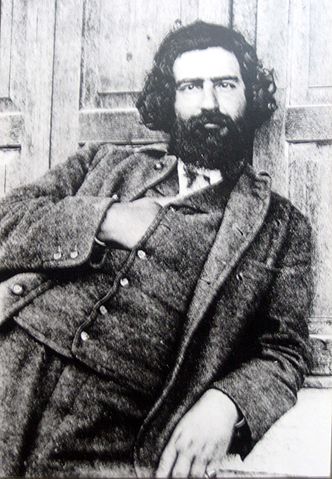

Who Was Segantini?

Giovanni Segantini (1858–1899) was born in the Trentino region of Italy, which was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time. He lost his citizenship as a child and lived his entire life as a stateless person. Despite this, he gained recognition as a young artist, winning a gold medal at the Amsterdam World’s Fair and exhibiting alongside Cezanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh at the 1890 Brussels exhibition.

Behind these achievements, however, his personal life was often unstable. In 1886, due to financial difficulties, he moved with his family to the mountainous region of Graubünden in Switzerland. He lived there until 1894, and Midday in the Alps was painted during this period.

Girl Knitting in Savognin(1888, Collection of Kunsthaus Zürich)

Style and Technique

Segantini used a technique similar to the Impressionists called Divisionism, where small strokes of color are placed side by side to create vibrant light effects. But unlike French pointillism (as seen in the work of Georges Seurat), Segantini applied fine linear brushstrokes, layering color in a way that preserved both brightness and clarity.

His landscapes have crisp contours and clear distant views, likely inspired by the transparent light and thin air of the Alpine climate. The style gives his works a sense of purity and stillness rarely found in more atmospheric Impressionist paintings.

This method, along with Segantini’s expressive precision, places him among Italy’s leading Divisionist painters, a movement that evolved independently from French Impressionism.

What Makes This Painting Special?

Divisionism is not widely known in Japan, but it offers a compelling alternative to the Impressionist view of nature and light. Segantini’s Midday in the Alps stands out for its intricate detail and serene atmosphere. The painting captures the crisp air and radiant light of the mountains with incredible realism.

When visiting the Ohara Museum, be sure to pause in front of this masterpiece. Take a moment to appreciate its quiet elegance and the artist’s unique vision of the Alpine world.

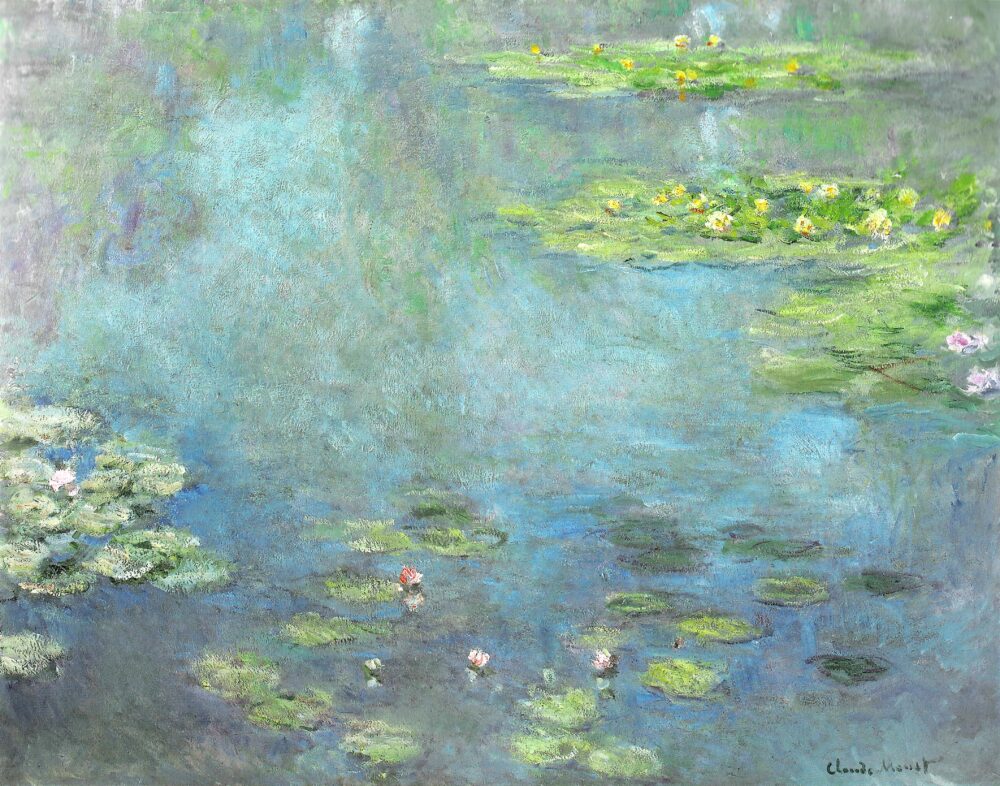

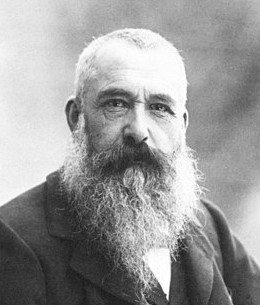

Claude Monet ,Water Lilies (1906)

About This Work (Click or Tap to Open)

Claude Monet, a founding figure of the Impressionist movement, spent the last decades of his life in the village of Giverny, northwest of Paris. There, he created a beautiful garden beside his home, famously known as the “Water Garden.” It became the main subject of his most iconic late works—the Water Lilies series.

This particular painting, created in 1906, belongs to the second phase of the Water Lilies series. Unlike the earlier works that often featured structural elements like the Japanese bridge, this version focuses entirely on the pond’s surface. Floating water lilies and gently rippling reflections fill the canvas with serene beauty.

Although the title refers to water lilies, Monet was especially fascinated by the reflections—how the sky, trees, and light constantly shifted depending on the time of day and weather. In this painting, you can see blue sky mirrored in the upper part of the canvas and even catch a glimpse of the water’s depth below. It feels as though your gaze is floating gently across the water’s surface.

Interestingly, Monet rarely sold his paintings outside of his contracted galleries. But this one became an exception. Torajiro Kojima, the artist and collector behind the Ohara Museum’s founding, reportedly gifted Monet a peony plant from Japan and personally persuaded him—resulting in the acquisition of this masterpiece.

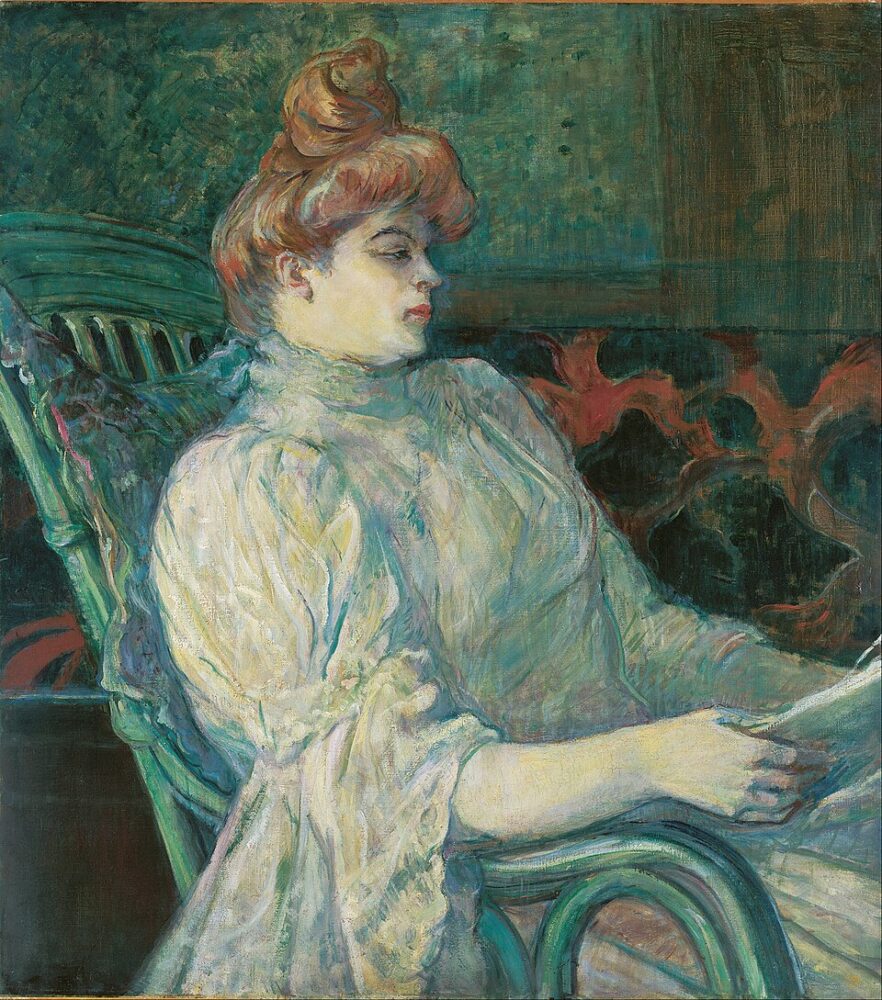

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec ,Madame Marthe X – Bordeaux (1900)

About This Work (Click or Tap to Open)

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was a French painter and printmaker best known for capturing the nightlife of Paris during the Belle Époque—a vibrant period of culture and entertainment at the end of the 19th century.

While his colorful posters are widely recognized in Japan and abroad, Lautrec also created many exceptional oil paintings, including this one, Madame Marthe X – Bordeaux. It was painted during his final days in the Bordeaux region of France.

Unlike his lively poster scenes with bold outlines and exaggerated movement, this work presents a quiet, intimate moment. The woman sits calmly with a book in hand, her gaze drifting into space. Lautrec’s expert drawing skills reveal her personality and inner world with subtlety and care.

The painting also showcases delicate lighting and nuanced color harmonies that are unique to oil painting—details not often seen in his graphic works. This piece is considered one of Lautrec’s late masterpieces, reflecting his quieter, more introspective side as an artist.

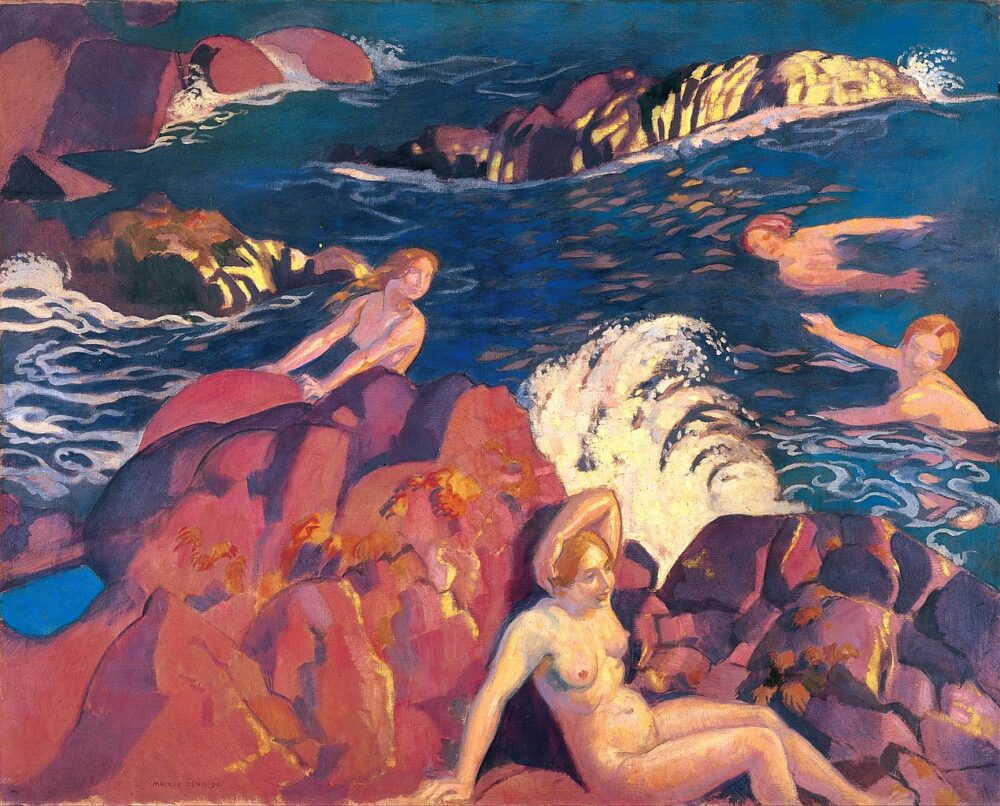

Maurice Denis, The Wave (1916)

About This Work (Click or Tap to Open)

Maurice Denis was a leading French artist of the Nabi movement—a group of painters who followed the Impressionists but took a very different approach. While the Impressionists focused on capturing natural light and fleeting moments, the Nabis emphasized decorative color, flat shapes, and strong composition.

The Wave was painted on the coast of Perros-Guirec in Brittany and shows women enjoying a day at the beach. Like the Impressionists, Denis chose an outdoor setting, but his focus wasn’t on natural lighting. Instead, he used bold color contrasts—pink rocks against blue sea—and stylized figures that give the scene a mythic or spiritual feel.

At the time, many artists were moving toward abstraction, influenced by Fauvism and Expressionism. Denis, however, looked back to classical ideas of structure and meaning. His work blended modern styles with timeless themes, offering a unique bridge between past and present.

This painting was purchased in 1920 during Torajiro Kojima’s second study trip to Europe. He met Denis in person and bought the work directly from the artist. Torajiro later noted in his journal that Denis’s studio had “almost no paintings,” suggesting this piece may have held special significance for Denis himself.

Henri Le Sidaner, Small Table at Dusk (1921)

About This Work (Click or Tap to Open)

Henri Le Sidaner was a French painter known for his quiet, atmospheric scenes, often associated with a style called “Intimism.” He gained recognition for his mysterious twilight landscapes that evoke peace and solitude.

Small Table at Dusk is a perfect example of his work. It shows a quiet alley along the Loing Canal in Nemours, France. The scene captures the moment just after sunset—a challenging time of day for artists—but Le Sidaner handles it beautifully with soft, cool tones. A single warm light glowing from a house adds a sense of life and contrast, drawing the viewer in.

Le Sidaner’s dreamy style was influenced by the Neo-Impressionists. He used a pointillist technique to create gentle shifts in color and light. But what makes his art truly poetic is what he leaves out: people. Instead of showing figures, he hints at human presence through empty chairs, half-set tables, or glowing windows. These subtle details invite viewers to imagine a story—one that might just be beginning.

img:by Calips

Torajiro Kojima, Watermill in the Village(1906)

About This Work (Click or Tap to Open)

“Watermill in the Village” is one of Torajiro’s early masterpieces, painted while he was still a student at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. It was exhibited at the National Industrial Exhibition, an important art and industry fair of the time.

To create this painting, Torajiro returned to his hometown of Nariwa in Okayama Prefecture. The setting is a small village watermill, where a mother, her child, and a young girl take a quiet break. Compared to his later Western-influenced works—like A Belgian Girl in Kimono—this piece shows a very different style.

Before studying abroad, Torajiro focused on capturing the quiet beauty of everyday Japanese life. One example is Going to School (1906), also housed in the Nariwa Museum of Art. These early works often highlight warm natural light and a gentle view of rural life.

When this painting was created, Japan was in a deep recession after the Russo-Japanese War. The mother in the painting wears simple clothing and nurses her baby between chores. This moment of modest strength and dignity may reflect Torajiro’s deep respect for the resilience of ordinary people.

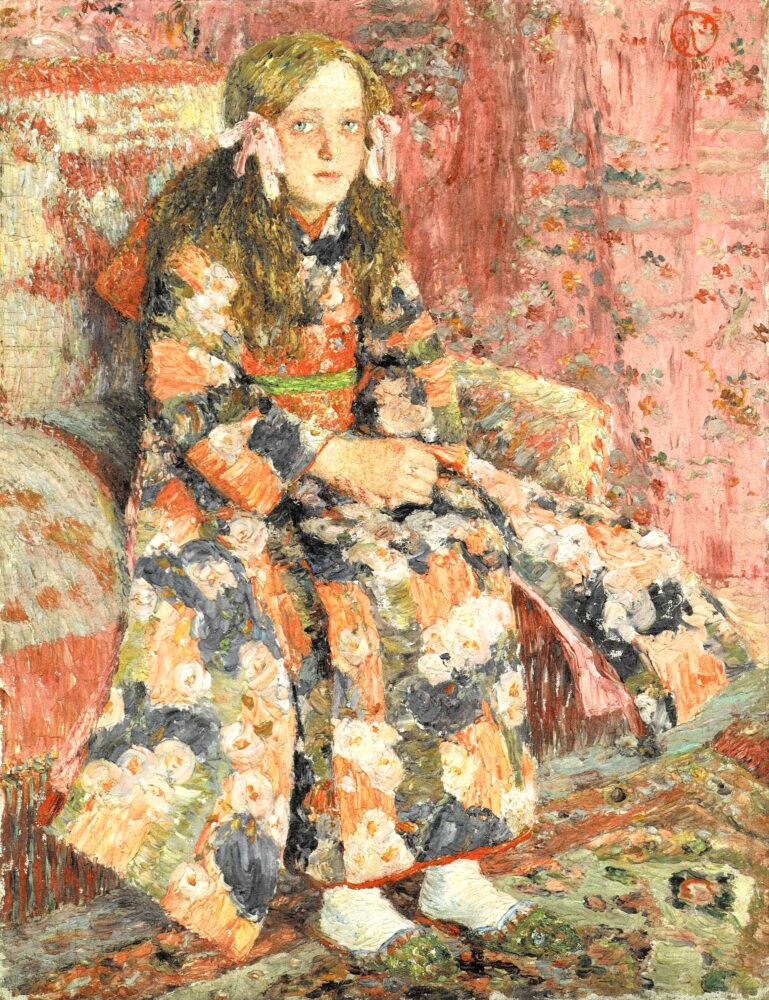

Torajiro Kojima, Belgian Girl Dressing Kimono (Little Neighbor), 1912

About This Work (Click or Tap to Open)

This painting, Belgian Girl Dressing Kimono (Little Neighbor), is a continuation of Torajiro’s earlier work, Belgian Girl Dressing Kimono, created the previous year. Based on her appearance and expression, the model is believed to be the same young girl as in the earlier piece.

Soft pink tones gently cover the entire canvas, highlighting the innocence of the girl seated on the sofa. The floral patterns on her kimono and the subtle hues of the background harmonize beautifully, creating a warm and intimate atmosphere. Compared to the 1911 version, this work feels more refined and poetic.

Like the earlier painting, this piece was also exhibited at the 1912 Salon National in Paris, where it was successfully accepted.

Visitor Information – Ohara Museum of Art

Location:1-1-15 Chuo, Kurashiki City, Okayama Prefecture, Japan

Kojima Torajiro Memorial Hall — A New Annex of the Ohara Museum

Opened in April 2025, the Kojima Torajiro Memorial Hall is a new annex of the Ohara Museum of Art.

It showcases works by Torajiro Kojima, the museum’s founding artist, along with ancient artworks from Egypt and West Asia that he collected during his travels.

While some of Torajiro’s paintings are displayed in the main building, this memorial hall allows visitors to explore more of his art and legacy in greater depth.

The building itself is a beautifully preserved piece of history. Originally constructed in 1922, it served as the Kurashiki Honmachi Branch of Chugoku Bank until 2016. The elegant retro-style exterior and carefully renovated interior offer a unique blend of art and architecture.

Located just a 2-minute walk from the main museum, the memorial hall is free to enter with your Ohara Museum ticket. If you’re visiting the Kurashiki Bikan Historical Quarter, don’t miss this chance to learn more about one of Japan’s key figures in modern art.

Access Map

References

・Tomoko Matsuoka, A Study of Kojima Torajiro, Chuokoron Bijutsu Publishing, November 25, 2004.

・Edited by Tomoko Matsuoka and Hideto Tokito, Kojima Torajiro, Sanyo Shimbun Publishing, May 28, 1999.

・Giovanni Segantini, Art Library Bis series, supervised by Beat Stutzer and Roland Wäspe, translated by Yuji Sueyoshi, Nishimura Shoten, March 20, 2011.

Comments