img: by 663highland

Located in the eastern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, the city of Fukuyama offers some truly unique and interesting spots. Movie lovers may recognize the nearby port town of Tomonoura, the setting for Studio Ghibli’s Ponyo, or enjoy a visit to Miroku no Sato, a retro theme park often used for period dramas.

As soon as you step off the train at JR Fukuyama Station, you’ll see Fukuyama Castle right in front of you—a rare sight from a Shinkansen platform! The castle was originally built by Katsunari Mizuno, a cousin of Tokugawa Ieyasu. In 2022, the north wall of the castle keep was restored with its iconic iron plating, making the castle’s appearance change depending on your viewing angle.

Although the inner and outer moats of Fukuyama Castle have mostly been filled in, the west side of the castle grounds has been transformed into a Cultural Zone. This area is home to several attractions, including the Hiroshima Prefectural Museum of History, which displays artifacts from the medieval town site of Kusado Sengen. But today, we’ll focus on one must-see destination: the Fukuyama Museum of Art.

Japanese and Western Masterpieces at the Fukuyama Museum of Art

Opened in 1990, the Fukuyama Museum of Art features a diverse collection ranging from works by local artists connected to the Seto Inland Sea region to Japanese modern Western-style paintings and European art.

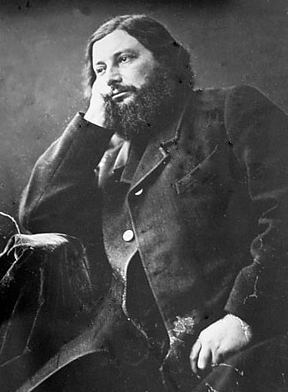

Highlights from the Japanese modern art collection include works by artists such as Ryusei Kishida and Sotaro Yasui. The Western collection includes pieces by renowned names like Marc Chagall, Gustave Courbet, and Giovanni Segantini. The museum rotates its exhibits regularly, combining its permanent collection with seasonal and special exhibitions—so every visit offers something new.

Another standout feature of the museum is its sword collection, donated by the late Yasuhiro Komatsu, an honorary citizen of Fukuyama. These beautifully crafted swords are presented as works of art, making the exhibition a must for both art lovers and history buffs.

Since exhibitions change throughout the year, we recommend checking the official website before your visit. Don’t miss your chance to see a favorite piece in person!

→ Fukuyama Museum of Art Official Website

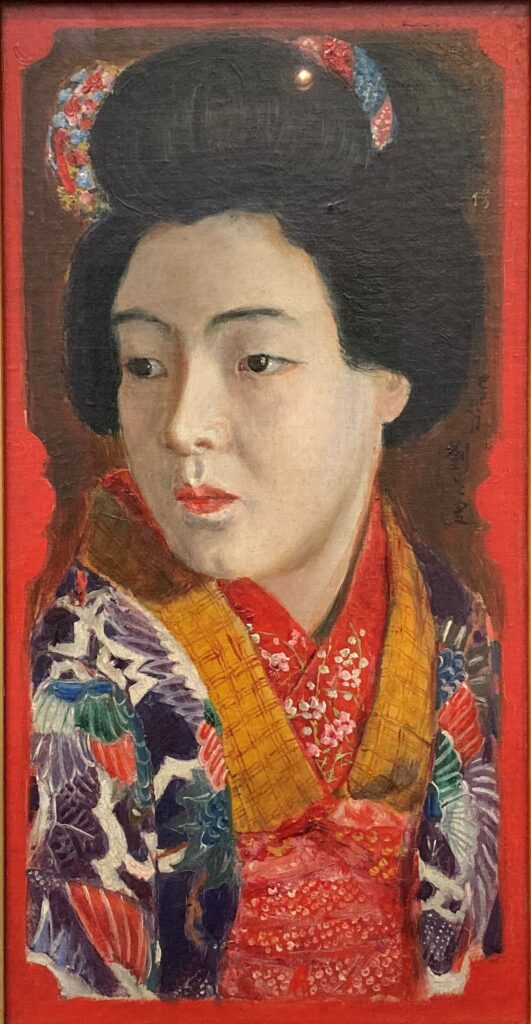

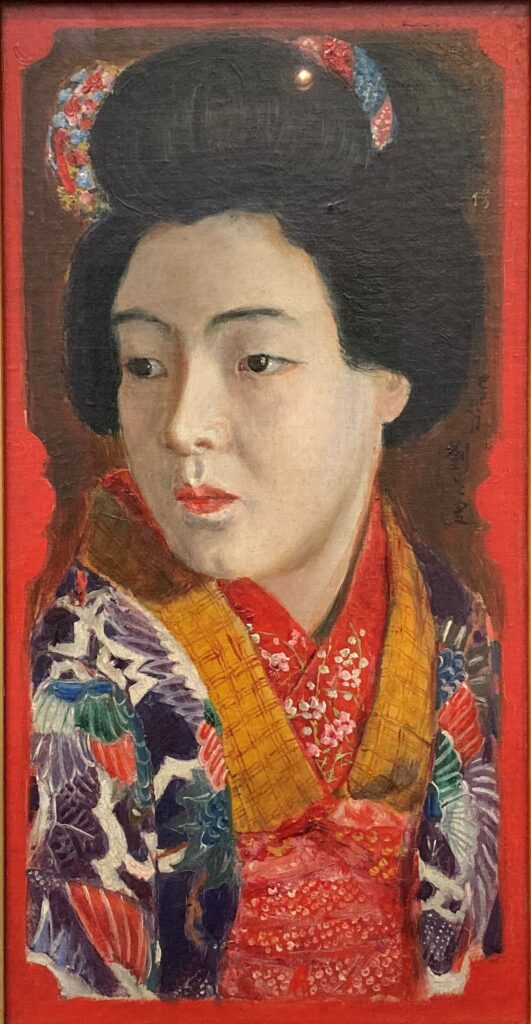

Reiko at Sixteen – The Final Portrait by Ryusei Kishida, Held at the Fukuyama Museum of Art

Title: Reiko at Sixteen (1929)

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 47.2 × 24.8 cm

Collection: Fukuyama Museum of Art

Among the many portraits that Ryusei Kishida painted of his daughter Reiko, Reiko at Sixteen—now housed at the Fukuyama Museum of Art—is especially important. This was the last Reiko portrait he painted before his death, and it reflects both his personal and artistic journey.

What Is a “Reiko Portrait”?

From the Collection of Tokyo National Museum Collection

Kishida is best known for a series of portraits of his daughter, commonly called the “Reiko Portraits.” The most famous one, Reiko Smiling (Tokyo National Museum), even appears in Japanese art textbooks. Over 70 works make up this series, including oil paintings, watercolors, and drawings.

The Fukuyama version of Reiko at Sixteen was painted in the same year Kishida passed away. Compared to his earlier works, this portrait shows a significant change in style and feeling. Behind that change lies Kishida’s evolving views on art—and life.

Realism, Eastern Aesthetics, and Kishida’s Artistic Philosophy

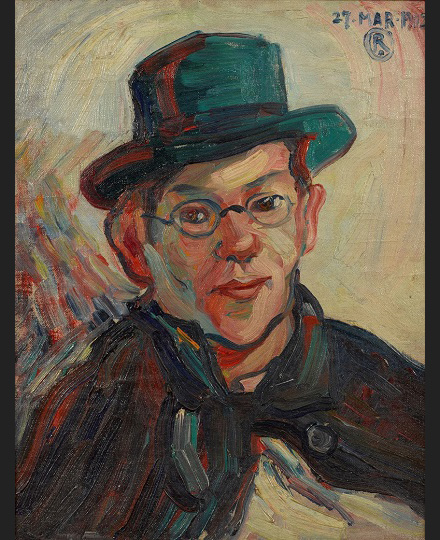

From the Collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

Kishida began painting in oils at the age of 17 under the mentorship of Kuroda Seiki. His early works show strong influences from Western artists like Vincent van Gogh and the Impressionists.

Over time, he became deeply interested in realism, especially in capturing the world “as it is.” One of his early Reiko portraits, Reiko at Age Five (1918), carries the dramatic shadows and tension found in Northern Renaissance artists like Albrecht Dürer, blending realism with an almost mystical quality.

From the Collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

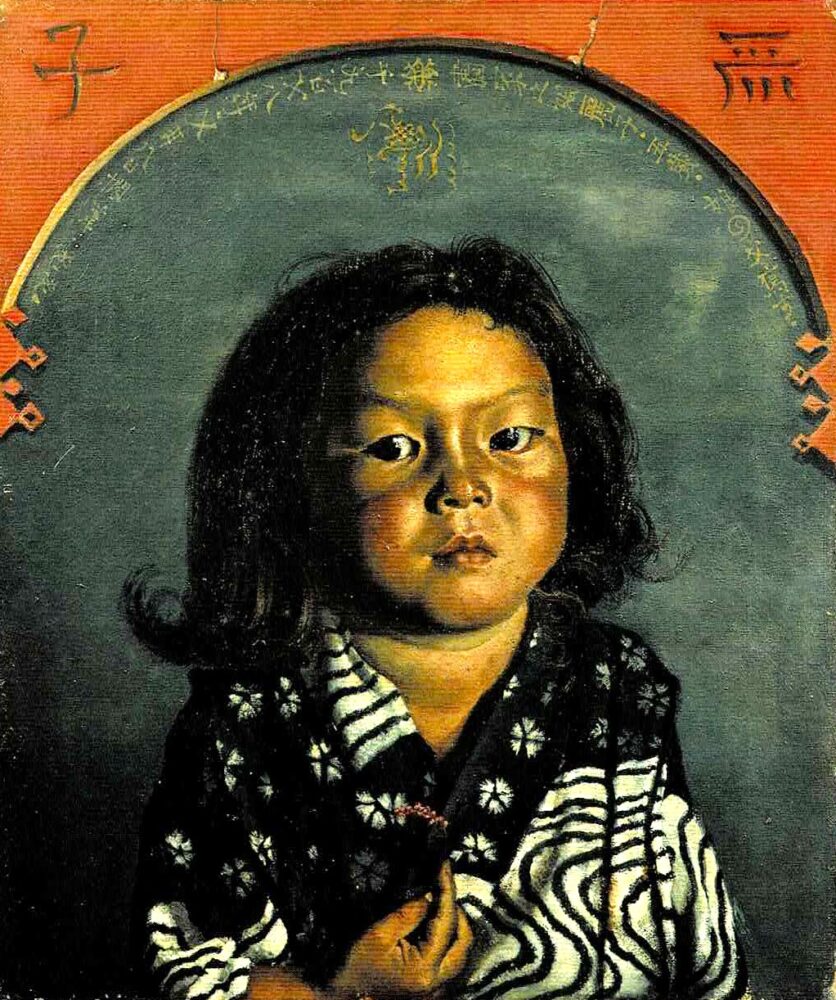

In the 1920s, Kishida turned his attention to East Asian art, studying Song and Yuan dynasty paintings and collecting ukiyo-e woodblock prints. This shift in focus influenced later works like Reiko Smiling, where he moved away from realism. Instead, he aimed for a spiritual or symbolic quality—expressed through simplified hands and feet, and a Buddha-like calm on Reiko’s face.

This change also reflects Kishida’s belief in the beauty of the ordinary—a concept he called “humble beauty.” He saw deep value in everyday life and sought to portray it without embellishment. Rather than technical perfection, Kishida appreciated a kind of raw, honest beauty—a theme closely aligned with Eastern aesthetics.

In his diaries, he wrote about becoming tired of detailed realism and expressed frustration with being bound by Western painting techniques. By contrast, he admired ukiyo-e and other Japanese works for their “profound realism” and “noble awkwardness.” He saw them as a path to discovering new forms of beauty.

Leading Up to Reiko at Sixteen

Kishida’s later works, like Wild Girl and Reiko in a Cold Mountain Wind, continued to show influences from traditional East Asian painting. However, around 1923, he painted fewer portraits of Reiko. One reason is that Reiko, then a teenager, grew tired of being his model—especially when seeing herself in the more eerie or exaggerated styles he sometimes used.

Several years later, Kishida painted Reiko at Sixteen. In fact, there are two versions of this painting: one held by the Kasama Nichido Museum of Art (painted in May 1929), and the other by the Fukuyama Museum of Art (painted in June 1929).

The Kasama version resembles earlier Reiko portraits, but the Fukuyama version is more flat in composition, resembling Japanese-style painting. Her round face and pale skin give off a warmth and softness that feel more personal. While it’s still an idealized portrait, it seems to express a father’s love more than an artist’s ambition.

Reiko herself reportedly loved this version. She once said the underpainting done in blue was so beautiful that she wished no colors were added. Her father smiled and replied, “It’ll become even more beautiful.”

From the Collection of the Kasama Nichido Museum of Art

A Father’s Final Portrait of His Daughter

Reiko at Sixteen, now held by the Fukuyama Museum of Art, seems to set aside the artist’s usual focus on realism and humble beauty. Instead, it feels like a straightforward, heartfelt tribute—a father capturing the grace and maturity of his daughter.

It’s natural to wonder: What would Kishida’s Reiko portraits have become if he had lived longer? That question adds another layer of depth when viewing this final, emotional masterpiece.

From the Collection of the Fukuyama Museum of Art

Featured Paintings at the Fukuyama Museum of Art

Gustave Courbet, The Wave (1869)

About This Work(Tap or Click to View)

Courbet was a leading figure of 19th-century French art and a pioneer of Realism. Rather than painting idealized beauty, he aimed to portray the visible reality of the world—a bold move at a time when history and religious paintings dominated the art scene.

This painting, The Wave, was created around 1869, when Courbet was in his fifties. In his later years, he often visited the Normandy coast in northwestern France, where he painted a number of seascapes. This particular work is more than a simple landscape—it’s a direct confrontation with the sea itself.

The sky and horizon are minimal. The composition is almost entirely filled with crashing, swirling waves. The heavy brushstrokes, layered paint, deep greens, and flashes of white light bring the texture and power of the sea to life.

For Courbet, nature wasn’t just a background—it symbolized raw, uncontrollable reality. The sea in this painting is both beautiful and terrifying, almost as if it’s about to swallow the viewer. It captures the truth of nature’s overwhelming force, beyond human control.

Torajiro Kojima, Outskirts of Ghent, Belgium (ca. 1909–1912)

About This Work(Tap or Click to View)

Torajiro Kojima is best known as the man who helped build the Ohara Museum of Art in Kurashiki by collecting masterpieces from abroad. But he was also a talented artist in his own right.

This painting was created during his time studying in Belgium, a period that greatly expanded his artistic style. Outskirts of Ghent, Belgium captures a quiet landscape with loosely painted trees, shimmering water, and a hazy sky. The rough brushwork may seem simple, but the painting has a calm, refreshing energy that brings a sense of peace to the viewer.

Especially notable is the use of soft whites and gentle color layers in the sky and reflections. Kojima’s brush gives the impression of light gently moving, almost as if you can feel the breeze and hear the stream.

The setting is Ghent, a city in Belgium. The small factory chimney in the distance shows a time when nature and modern industry coexisted—a common scene in early 20th-century Europe.

While Kojima is often remembered as a collector, this painting reminds us of his sensitive and poetic vision as an artist. It’s a wonderful example of how deeply he connected with the landscapes he encountered.

Masterpieces of Japanese Sword Art

Explore National Treasures at Fukuyama Museum of Art

Thanks to a generous donation from Mr. Yasuhiro Komatsu, an honorary citizen of Fukuyama, the Fukuyama Museum of Art now holds one of the most impressive sword collections in western Japan. Among these are seven swords designated as National Treasures, making it the second-largest National Treasure sword collection in Japan—tied with the Tokugawa Art Museum and just behind the Tokyo National Museum, which owns 19.

This exceptional collection showcases the deep beauty and cultural importance of Japanese sword craftsmanship, offering visitors a unique opportunity to appreciate these masterpieces beyond their historical role as weapons.

Tachi Sword by Kunimune (Kamakura Period)

—National Treasure

About This Work(Tap or Click to View)

This rare tachi sword, made by the famed swordsmith Kunimune from Bizen Province (modern-day Okayama), is one of only four Kunimune swords designated as National Treasures in all of Japan. Seeing it in person is a must—not only for sword enthusiasts, but for anyone interested in traditional Japanese craftsmanship.

But what exactly is a tachi?

—from the collection of the Tokyo National Museum

img: by Kakidai

Unlike the earlier straight swords (called chokutō), tachi appeared in the mid-Heian period with a curved blade, designed for mounted warriors. Unlike the later katana (uchigatana), the tachi was longer and had a deeper curve, intended to be used by slashing downward while riding on horseback.

As warfare evolved toward close combat on foot, the more compact katana became popular. Tachi gradually faded from use—but their elegance and power continue to fascinate viewers to this day.

At Fukuyama Museum of Art, you can admire the spirit and mastery of Kunimune in this extraordinary sword—truly a national treasure in every sense.

Katana Attributed to Rai Kunimitsu (Kamakura Period)

—Important Cultural Property

About This Work(Tap or Click to View)

Another highlight of the museum’s collection is this elegant katana, officially designated an Important Cultural Property. Though unsigned, it is attributed to the legendary swordsmith Rai Kunimitsu based on expert analysis of its style and craftsmanship.

Why is it unsigned?

Originally, this blade was likely a tachi, a longer sword designed for mounted combat, and it would have borne the maker’s signature (called a mei) on the tang (nakago). However, during the Warring States period, many such swords were shortened in a process known as suriage. This modification was made to adapt older tachi for use as katana—shorter, more practical swords suited for hand-to-hand combat on foot. In the process, the original signature was often lost.

At the time, swords were practical weapons, not decorative objects. Function came first, even if it meant cutting down a beautifully signed blade. Today, we might gasp at the thought—but back then, a sword’s value was in how well it performed.

Another fun detail: tachi and katana are worn differently.

Tachi were suspended from the waist with the blade facing down.

Katana were worn with the blade facing up, tucked into the belt.

This difference is reflected in how they’re displayed at museums, including Fukuyama.

Despite losing its original signature, this katana—once a tachi—radiates the strength and artistry of Rai Kunimitsu. It stands as a silent but powerful reminder of Japan’s samurai legacy.

Visitor Information: Fukuyama Museum of Art

Address: 2-4-3 Nishimachi, Fukuyama City, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan

Comments