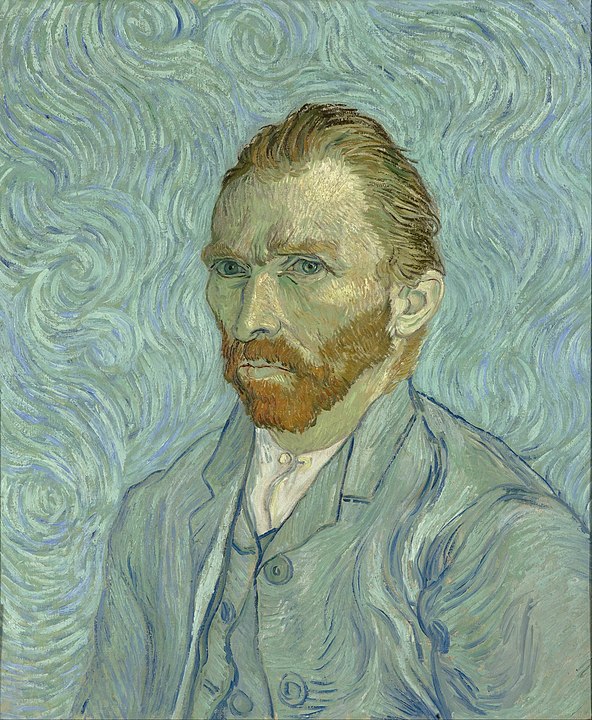

Today, Van Gogh’s bold colors and expressive brushstrokes are celebrated around the world. But during his lifetime, he sold very few paintings and lived in poverty and isolation. Because of this, many people picture him as the “tragic genius” who ended his own life.

Theo – The One Person Who Truly Believed in Van Gogh

Theodorus van Gogh (1857–1891) Theo, Vincent’s younger brother, was the one person who never stopped believing in his art.

While working as an art dealer in Paris, Theo had just started a family—his first child had recently been born. Yet, he was also sending money home to support their parents, which made his finances very tight.

When Van Gogh visited Theo in Paris, he saw firsthand how hard his brother’s life was.“I’ve become such a burden to him,” and this weighed heavily on his mind.

After returning to Auvers-sur-Oise, Van Gogh wrote letters to Theo expressing concern about his brother’s financial struggles. Many believe that this growing sense of guilt and anxiety pushed him to the edge.

The Day of the “Suicide” Incident

So, what exactly happened on that tragic day?

On July 27, 1890 , Van Gogh had lunch as usual and then went out to paint.Ravoux Inn , wounded in the stomach by a gunshot. He was pale, limping, and in great pain. His host family immediately called a doctor, but the wound was too serious to treat effectively.

What really happened that day remains one of art history’s greatest mysteries.

A Day Without Letters – Wrapped in Mystery

One reason we know so much about Van Gogh’s life is because he wrote hundreds of letters to his brother Theo and close friends.

The most important of these is an interview given in 1954 by Adeline Ravoux , the daughter of the innkeeper where Van Gogh stayed.

Adeline Ravoux’s Testimony

According to Adeline’s account:

“Vincent had gone to the wheat field where he had painted previously, it was situated behind the Auvers chateau… The chateau was more than a half – kilometer from our house. It was reached by going up a steep hill, shaded by great trees. We do not know how far he got from the chateau. In the course of the afternoon, on the road that passes under the chateau wall – so my father understood – Vincent shot himself with a revolver and fainted. The freshness of the evening revived him. On all fours he sought the revolver to finish himself off, but could not find it (and it was not found the following day). Then Vincent gave up looking and came down the hill to regain our house. ” 1

This story was based on what Adeline’s father, Gustave Ravoux , reportedly heard directly from Van Gogh himself as he lay dying.

” Portrait of Adeline Ravoux His Final Moments and Farewell

Van Gogh received emergency treatment from local doctors, but the wound was too deep for him to survive.

On the morning of July 29, 1890 , with his younger brother Theo by his side, he quietly took his last breath.

” This is how I would like to go.

He was 37 years old .

” Sketch of van Gogh on His Deathbed “ Was Van Gogh’s Death Really a “Suicide”?

If Adeline Ravoux’s testimony is true and Van Gogh really took his own life, there are still many mysteries and unanswered questions that make the “suicide theory” hard to accept.

1. The Missing Gun and Art Supplies

The first mystery is the missing gun .

According to the testimony, Van Gogh went out to a wheat field and shot himself in the stomach with a revolver. When he regained consciousness sometime later, the gun had completely disappeared. He searched for it but couldn’t find it, then gave up and walked back to the inn.

But think about it — how could the gun just vanish ?

Even stranger, the revolver was never found , not even after the investigation.strength or reason to do so in his critical state.

So where did the gun go?

There were local rumors that the innkeeper, Gustave Ravoux , had lent it to him, but there’s no real evidence of that.

Another mystery is the disappearance of his art supplies .

Van Gogh always carried his easel, canvas, and paints when he went out to paint, yet none of these items were ever found at the supposed scene or along the way.

This “missing equipment” is one of the reasons why the exact location of the shooting has never been identified.

2. The Strange Position of the Wound

Another detail that raises doubts is the location of the gunshot wound .

Van Gogh was shot just below the left side of his chest — about three to four centimeters under the nipple.

If he truly intended to end his life, it would have been more typical to aim at the head or mouth , not the stomach.

Moreover, the doctors who treated him reported no sign of a contact wound — the kind of burn or mark that appears when a gun is fired with the muzzle pressed directly against the skin.from a distance , which seems strange for a suicide attempt.

Even though the shot was fired at close range, the bullet did not pass through his body ; instead, it remained inside his abdomen.

In fact, the bullet’s angle suggests that the gun was aimed slightly downward , which would be quite unnatural if he were shooting himself.

3. Could It Have Been an Impulsive Act During a Seizure?

By July 1890, when Van Gogh’s death occurred, he was still living under the shadow of his past mental illness — the same condition that had first appeared in Arles in 1888.

During these episodes, Van Gogh sometimes showed dangerous behavior , like trying to swallow paint or turpentine.spontaneous suicide during a seizure .

But is that really possible?

According to Dr. Théophile Peyron , who treated him in Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh’s seizures usually lasted at least a week , during which he couldn’t speak coherently or function normally.

If he had been in the middle of such an episode, he likely wouldn’t have been able to walk back to the inn, much less have a clear conversation.

Yet after being shot, Van Gogh walked down the hill , returned to the Ravoux Inn, and spoke with both Gustave Ravoux and his brother Theo .calm and fully conscious — hardly the state of someone suffering from a severe seizure.

All of this suggests that the idea of an impulsive suicide during a mental attack doesn’t quite add up.

4. Did Van Gogh Really Plan to Take His Own Life?

If his mental illness wasn’t the direct cause…

A common theory says that he took his life because he didn’t want to burden his brother Theo any longer.

Since 1880, when Van Gogh first decided to become an artist, Theo had supported him both financially and emotionally.Theo’s finances were stretched very thin .

When Van Gogh visited Paris and saw how hard his brother’s life really was, he was deeply shocked.

At first glance, this theory seems convincing.

Van Gogh came from a deeply religious Protestant family.

In one of his letters to Theo, Van Gogh even wrote:

” Look here — about now or ever — making yourself scarce or disappearing — neither you nor I must ever do that, any more than a suicide. ” 2

And there’s another important point to consider.

The two brothers had exchanged hundreds of intimate letters over the years.

Yet, Van Gogh left no suicide note .no hint of despair or farewell.

Would someone truly planning to die be ordering new paints?

The “Accidental Shooting” Theory

In recent years, a new theory has gained attention—one that challenges the long-accepted story of Van Gogh’s suicide.“accidental shooting theory.”

This idea was introduced by American biographers Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith , authors of Van Gogh: The Life .shot by a local teenager , rather than taking his own life.

The Testimony of René Secrétan

It all started with the release of the 1956 film Lust for Life. René Secrétan claimed that the Van Gogh portrayed in the film was nothing like the real man he had once known.

He told French writer Victor Doiteau that he had actually met Van Gogh in the summer of 1890.

At the time, René was 16 years old—the son of a wealthy Parisian pharmacist and a student at the prestigious Lycée Condorcet , where famous figures like Proust and Cocteau had also studied.Auvers-sur-Oise , together with his older brother, Gaston .

That same year, Van Gogh had just moved to Auvers in the spring.Van Gogh was just a “strange old man”—someone to tease for fun.

At first, the pranks were harmless.

For example:

putting salt in Van Gogh’s coffee,

hiding a snake in his paint box,

smearing chili on his brushes (Van Gogh had a habit of licking them to shape the tips).

Each time Van Gogh got upset, the boys laughed even harder.

The Revolver and the Cowboy Play

Drawing by Van Gogh (June–July 1890, Louvre Museum)After seeing Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show at the 1889 Paris Exposition, René became fascinated with the Wild West and began to enjoy pretending to be a cowboy.

And of course, what’s a cowboy without a revolver?

René owned an old .38-caliber revolver —real, though unreliable, sometimes misfiring.

According to his own account, the gun had originally belonged to Gustave Ravoux , the innkeeper and father of Adeline Ravoux .

This leads to a chilling question:the same gun that shot Van Gogh?

The Missing Gun

One question still remains: What happened to the gun that shot Van Gogh?

Testimony of René Secrétan

In a 1956 interview, René Secrétan claimed that his revolver had been “stolen by Van Gogh.”

René added that he didn’t even notice the gun was missing until he left Normandy.

Testimony of Adeline Ravoux

Adeline Ravoux, the daughter of the innkeeper where Van Gogh stayed, had been interviewed many times since the 1950s.Van Gogh actually belonged to her father, Gustave Ravoux.

She also added that Van Gogh had borrowed the gun from Gustave to scare away crows.

Moreover, Van Gogh — who once aspired to become a pastor — disliked harming living creatures.3 “ a sign and proof of approval and blessing from Above” 4

Conflicting Testimonies

When we compare the two testimonies , they clearly contradict each other:

René said: “Van Gogh stole the gun .”Van Gogh borrowed it from my father. ”

So which one is true?both hiding something?

The mystery of Van Gogh’s death may depend on the truth about this missing weapon.

perhaps Van Gogh’s death wasn’t a suicide ,murder .

Reconsidering the Incident

Looking at all the testimonies and circumstances, the theory that René Secrétan shot Van Gogh suddenly starts to sound surprisingly convincing.

So, let’s follow the events of that day—under the assumption that René was the one who shot Van Gogh.

The Day of the Incident: Van Gogh’s Movements

July 27, 1890.

At some point, he may have run into René Secrétan—or perhaps they had already been drinking together at a tavern earlier.

That evening, something happened between Van Gogh and René.

The Gunshot

Whether it was a misfire from an old pistol or a scuffle between a drunk Van Gogh and the mischievous René, no one knows for sure.

Whatever the cause, René must have turned pale with shock after realizing he had shot someone.

As Van Gogh limped back toward the Ravoux Inn, René and his companions likely panicked and tried to hide the evidence.

Gustave’s Responsibility

Another key figure enters the story here: Gustave Ravoux , the innkeeper.

When Gustave heard that Van Gogh had been shot, he must have immediately suspected what had happened.

(We don’t know why Gustave gave René the pistol, but considering René came from a wealthy family, it’s easy to imagine that he was treated with some degree of indulgence.)

The next day, July 28 , when the police came to question Van Gogh, Gustave interrupted the conversation for some reason.

Van Gogh’s Silence and the “Invented Story”

Curiously, Van Gogh himself never revealed who shot him.

It’s likely that Gustave passed this story on to Adeline Ravoux , but she probably knew more than she let on.

Solving the Mysteries

If we assume that Van Gogh died because of an accidental or unintentional shooting by René Secrétan, several long-standing mysteries finally make sense:

The missing gun

The missing painting supplies

The absence of powder burns on the wound

The fact that the bullet didn’t pass through the body despite being fired at close range

All of these can be naturally explained under the “homicide theory.”

And yet, one final mystery remains—Why did Van Gogh never reveal René’s name , not even to the police or to his beloved brother Theo?

Why Did Van Gogh Protect René Secrétan?

When we look at the case from the perspective of the “murder theory,” many mysteries about Van Gogh’s death suddenly make sense.

Why did Van Gogh protect René Secrétan?

During police questioning, when asked, “Did you want to kill yourself?” Van Gogh answered vaguely, “I think so.”

Considering all of René’s cruel pranks, Van Gogh surely felt upset many times.

How Did Van Gogh See “Death”?

In their biography Van Gogh: The Life , Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith suggest that Van Gogh might have welcomed death rather than feared it.

Van Gogh had strong Protestant beliefs and saw suicide as a sin.

” I’ve very often told myself that I’d prefer that there be nothing more and that it was over. ” 5

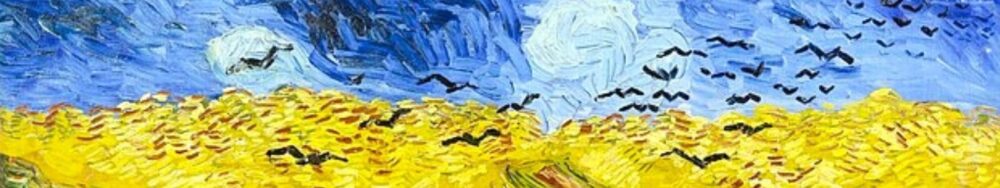

Later, while painting Wheat Field with a Reaper in Saint-Rémy, he described death in poetic terms, comparing the reaper to “the grim reaper” and the harvested wheat to “human lives.”

” But in this death nothing sad, it takes place in broad daylight with a sun that floods everything with a light of fine gold. ” 6

So while Van Gogh rejected the idea of taking his own life, he did not see death itself as something dark or tragic.a form of salvation .

” Wheatfield with Reaper at sunset ” (September 1889) A Punishment and a Gift?

If we look further back in time, during his days as a preacher, Vincent van Gogh was known for his harsh self-punishment. He would strike his own back with a stick and even sleep on the ground instead of in a bed.

Naturally, people around him were shocked. His father, Theodorus, tried to have him admitted to a mental hospital, but Van Gogh became furious and refused.

This episode shows Van Gogh’s extreme sense of dedication, but it also reveals something deeper — a strong feeling of guilt and a desperate wish for spiritual salvation.

And then came the fateful summer of 1890.

It was during this time that the shooting incident involving René Secrétan occurred.

Perhaps, for Van Gogh, it felt like an event destined to happen.

He did not fear death; on the contrary, he seemed ready to accept it.“This is salvation sent from heaven.”

And that is why, on his deathbed, he told Theo quietly:

” This is how I would like to go.

Those words were not born of regret or apology.calm acceptance of a man who had finally come to terms with the end .

Summary: The Preexisting Image of “Suicide”

So far, we’ve looked at Van Gogh’s death from the perspective of the murder theory .

The traditional “suicide theory” was based on unclear and inconsistent information. Many contradictions appear when we assume Van Gogh tried to take his own life. However, most of those contradictions make sense if we consider the murder theory. The most likely suspect is René Secrétan. Van Gogh, who secretly wished for death, chose to protect René instead of blaming him.

Personally, I find the murder theory quite convincing, as it explains almost every mystery surrounding his death.suicide theory still remains the mainstream view today.

The Distorted Image of Van Gogh’s Art

Van Gogh’s dramatic life, his passion, and his impulsive actions have long shaped the image of a “tragic genius.”

Take his famous painting, Wheatfield with Crows final work , and in the 1956 film Lust for Life , Van Gogh is shown committing suicide right after painting it.

Interestingly, even the title Wheatfield with Crows wasn’t given by Van Gogh himself.

Even if the birds in the painting really are crows, Van Gogh, as mentioned earlier, saw crows as sacred creatures.This suggests that the painting may have been unfairly burdened with the weight of “death” and “suicide” simply because of preconceived ideas .

In truth, this work might be better appreciated as a vibrant example of Van Gogh’s unique use of blue and yellow , his favorite complementary colors.

” Wheatfield with Crows ” (July 1890) Another often-misunderstood painting is Daubigny’s Garden That led to speculation that the cat symbolized Van Gogh’s approaching death or suicide.

However, recent research shows that the overpainting wasn’t done by Van Gogh at all—it was added later by a restorer.

As we can see, linking every mysterious element of his work to “suicide” can sometimes make us overlook the artist’s true intention and creativity .

Even if the murder theory turns out to be wrong,only through the lens of tragedy.

” Daubigny’s Garden ” (July 1890) About René Secrétan After a mischievous childhood, René Secrétan went on to work as a banker and even managed a gold mine in Johannesburg, South Africa. Remarkably, he eventually rose to become a director at a Swiss reinsurance company. After retiring, he spent his later years quietly in a small town in France.

In 1956, at the age of 82, he revealed in an interview that he had once met Van Gogh. But why did René decide to speak up after so many years? If he simply wanted attention, he could have done so in the 1920s or 1930s, when Van Gogh’s fame was already spreading worldwide—it would have made a much bigger impact.

What’s more, René described in surprising detail the pranks he had played on Van Gogh. Many of these stories actually made him look bad. It makes you wonder—why share such things at all? Perhaps he was burdened by a long-lasting sense of guilt that had haunted him for decades.

If we assume the “murder theory” is true, it’s possible that, even though it was a youthful mistake, René never forgave himself for playing a role in Van Gogh’s death. And since Van Gogh never mentioned his name—not even at the end—René might have felt a mix of regret, gratitude, and deep sadness that words could hardly express.

Maybe that’s why he finally chose to speak out—to confess what he had done and, in some small way, make peace with his conscience. At the same time, he may have wanted to correct the distorted image of Van Gogh that had been popularized by movies.

Still, René never admitted to the shooting itself. This could have been an act of self-protection, or perhaps he wanted to shield his family from the consequences. By at least talking about Van Gogh, he might have hoped to express some respect—or even a silent apology.

René Secrétan passed away the following year, in 1957—taking the truth with him.

Further Reading

・Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith. Van Gogh: The Life . Translated by Kazuya Matsuda, vol. 2, Kokusho Kankokai, 2016.

Sources

スポンサードリンク ( Sponsored link )

Comments