A Breath of Art in the Heart of Tokyo

If you’re looking to explore art in Tokyo, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (MOMAT) is a must-visit. Just a short walk from Takebashi Station, this museum is located along the peaceful moat of the Imperial Palace, offering a quiet escape from the busy city.

While some people might think of art museums as formal or intimidating, MOMAT is different. The moment you step inside, you’ll feel a calm and welcoming atmosphere that naturally draws you into the world of art.

Discover 100 Years of Japanese Art with the “MOMAT Collection”

The museum’s main highlight is the permanent exhibition known as the MOMAT Collection. This exhibit takes you on a chronological journey through Japanese art, from the Meiji period to today. You’ll find works by famous artists like Kōtarō Takamura, Ryūsei Kishida, and Tsuguharu Fujita, alongside impressive pieces of contemporary and abstract art.

The displays are refreshed regularly, so even repeat visitors will find something new. With well-written captions and an easy-to-follow layout, MOMAT is also beginner-friendly—making it easy to simply enjoy and feel the art without pressure.

For art lovers, MOMAT isn’t just a place to look at paintings—it’s a place for thoughtful dialogue between the past and the present. If you’re visiting Tokyo, take your time and fully enjoy this inspiring museum.

Masterpieces That Tell the Story of Modern Japanese Art

MOMAT holds a vast collection of around 14,000 works, with about 200 pieces on display at any given time. It’s truly a treasure trove for art lovers.

One standout feature is that 18 of the artworks are designated Important Cultural Properties—a rare and valuable experience you won’t want to miss.

Below, we’ll introduce some of the must-see masterpieces from this incredible collection.

Please check the official website for the latest information on current exhibitions.

▶ MOMAT Official Website

Hogai Kano, “Nio(Buddhistguardian) Seizing an Evil Spirit” (1886)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

The Last Master of the Kano School, Rediscovered by the West

Hogai Kano stood at a turning point in Japanese art during the early Meiji period. He was a key figure of the historic Kano school, which had dominated Japanese painting from the Muromachi to Edo periods. Hogai is often described as the last great Kano artist—and at the same time, as the one who opened the door to modern Nihonga (Japanese-style painting).

However, life after the Meiji Restoration wasn’t easy for him. With the loss of his samurai status, he also lost many of his commissions. He struggled financially and even tried raising silkworms to make a living—but that too failed.

Just when things seemed hopeless, an unexpected supporter appeared: Ernest Fenollosa, an American philosopher who strongly believed in the value of Japanese-style painting in a time when Westernization was sweeping the country. Encouraged by Fenollosa, Hogai began creating bold and innovative works in the final years of his life.

A Historic Work Blending Tradition and Innovation

One of his greatest achievements, Nio(Buddhistguardian) Seizing an Evil Spirit, reflects that creative breakthrough. It shows a fierce Buddhist guardian overpowering a demon with one hand—a dramatic composition full of energy. The powerful muscles and detailed clothing decoration combine traditional Kano techniques with Western-style depth and perspective, inspired by Fenollosa’s influence.

A highlight of this painting is its vivid color. Recent research shows that Hogai used Western pigments like Prussian blue and viridian, which were originally meant for oil painting. He adapted them using traditional Japanese nikawa (animal glue) to fit the Nihonga method. The result is a matte texture with rich, vibrant colors—uniquely Japanese, yet modern in feel.

Though it’s a Nihonga painting, it also has a Western flavor. This blend of old and new is what makes Hogai’s work so special—and why Nio(Buddhistguardian) Seizing an Evil Spirit is more than just a religious painting.

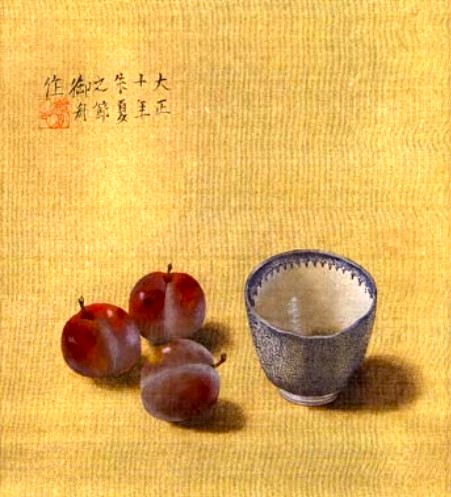

Gyoshu Hayami, “Houses in Kyoto”, “Houses in Nara” (1927)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Modern Nihonga Artist with a Bold, Experimental Spirit

Gyoshū Hayami was an important figure in early 20th-century Japanese art, active during the Taishō and early Shōwa periods. Known for his realistic Nihonga paintings, he was influenced by Western painter Ryūsei Kishida, as well as the avant-garde movements of Cézanne and Cubism.

His work Houses in Kyoto and Nara was created during a period when he was exploring new artistic expressions beyond traditional Nihonga boundaries. It’s a prime example of his free, experimental approach.

Known for its realistic depiction from this period.

A Cubist-Inspired View of Japanese Streetscapes

At first glance, the painting looks like a peaceful scene of traditional Japanese houses. But look closer, and you’ll notice the sharply defined forms and geometric lines. These show a Cubist influence—an approach that analyzes objects based on structure and form.

Despite this modern interpretation, the work still functions beautifully as a landscape. In the Nara section, the white steep-roofed Yamato-style houses contrast with the warm tones of earthen walls. A handcart subtly adds a charming narrative detail.

In the Kyoto section, the focus shifts to a red, curved roof—its rounded shape a signature of traditional Kyoto architecture. Placed against the straight-lined roofs in the foreground, the contrast in forms is striking and visually dynamic.

Fearless in Evolving His Artistic Style

Gyoshū was never afraid to change his style. He remained grounded in Japanese tradition, yet constantly sought new forms of expression. From realism to abstraction, decorative art to the avant-garde—he explored each freely, guided by a sincere artistic curiosity.

Houses in Kyoto and Nara is a perfect example of this spirit. While capturing the essence of Japan’s historic towns, the painting also invites viewers to consider deeper layers of form and structure—offering a fresh perspective that still feels modern today.

Sanzo Wada, “South Wind” (1907)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

img:wikipedia commons / Collection of Tanyo Museum

About the Artist

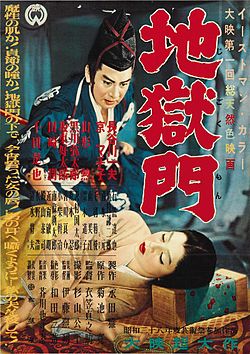

Sanzo Wada (1883–1967) was a Western-style painter who was also a pioneer in color theory in Japan. He published The Complete Guide to Color Harmony, later revised as the Color Dictionary, which is still used in modern design. Wada also worked in film and costume design—his color direction for the film Gate of Hell (1953) won the Grand Prix at Cannes and an Academy Award for Best Costume Design.

The first color film produced by Daiei, which later merged with Kadokawa Pictures.

The Story Behind “South Wind”

This powerful painting was inspired by a dramatic real-life event. While still a student, Wada was caught in a storm while traveling by sea and was shipwrecked on Izu Ōshima Island. Deeply moved by the experience, he returned there many times to sketch and study the landscape and people.

At the center of South Wind stands a strong, determined man facing the wind and sea. He represents not just Wada’s journey, but also a deeper connection with nature and resilience. The vivid contrast of deep ocean blues and warm orange tones shows Wada’s bold use of color and light. You can feel the unseen ocean just outside the frame, pulling the viewer into the story.

Naojiro Harada, “Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon” (1890)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

About the Artist

Naojiro Harada (1863–1899) was a key figure in the early days of modern Western-style painting in Japan. After studying under Yuichi Takahashi in Tokyo, he traveled to Munich and studied realistic techniques under Gabriel Max. While abroad, he became friends with author Ōgai Mori, who later based a character on Harada in his novel The Foam on the Waves.

A Bold and Controversial Masterpiece

Harada’s Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon shocked audiences when it was unveiled in 1890. Unlike traditional Buddhist art, which favored flat, decorative styles, Harada used Western oil painting techniques to create shadows, depth, and lifelike presence. The Kannon figure looks like a real, physical being riding a dragon, rendered with stunning detail and scale.

But not everyone was ready for such innovation. Some critics mocked the piece, saying the Kannon looked like she was “walking a tightrope.” While the work didn’t win awards at the time, it broke boundaries and challenged artistic norms in Meiji-era Japan.

A Vision Before Its Time

Harada died young at just 36, before his work could be fully appreciated. Soon after, lighter, French Impressionist styles became popular in Japan, led by artists like Kuroda Seiki. But Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon reminds us of another possible path Japanese art could have taken—one that embraced realism, drama, and deep academic roots.

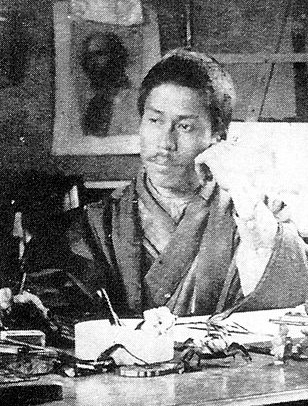

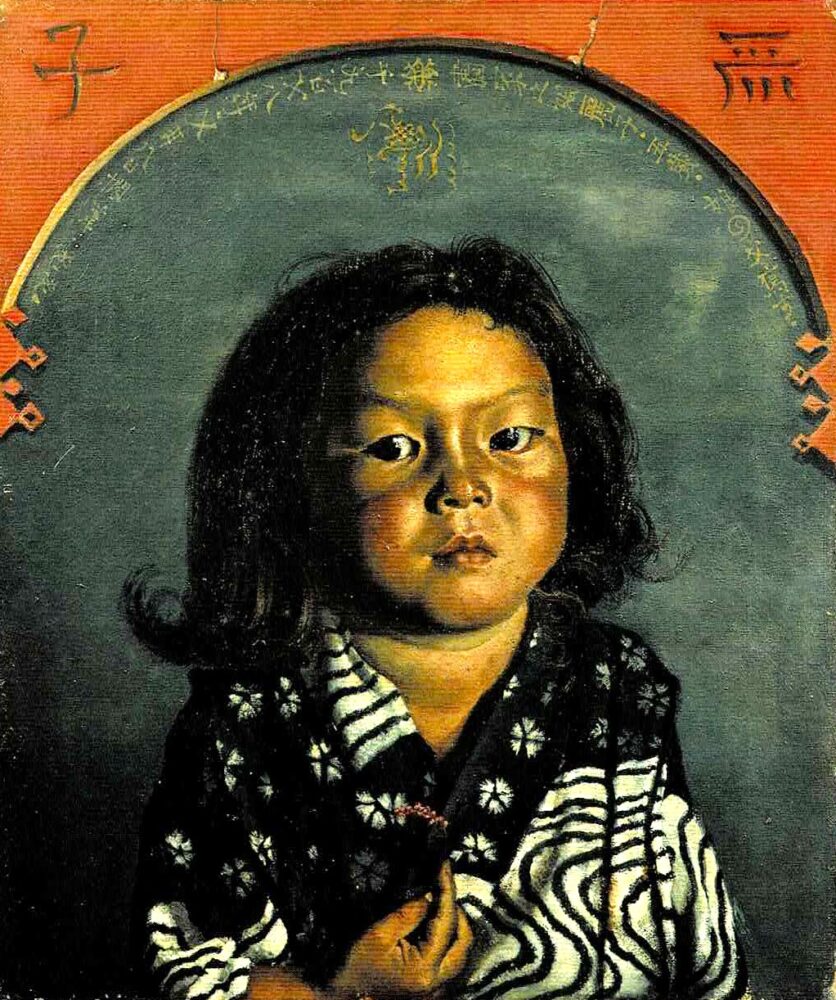

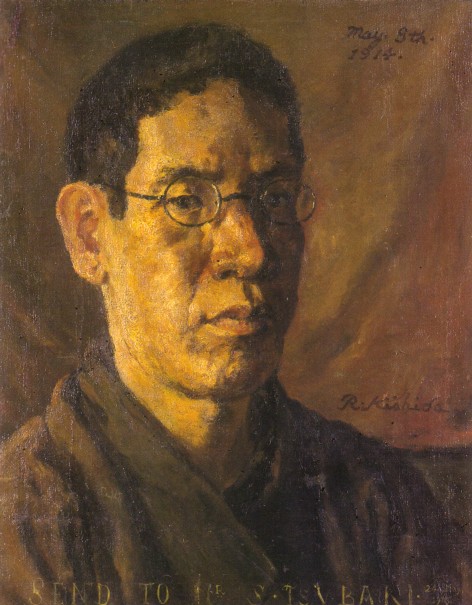

Ryusei Kishida, “Reiko, Five Years Old” (1918)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Powerful Portrait Through a Father’s Eyes

Ryusei Kishida is known for dramatically shifting his painting style throughout his career. Early on, he was influenced by Van Gogh, using vivid colors and bold brushstrokes. But in the mid-1910s, his focus turned to classical Western painting, leading him to pursue intricate realism.

This piece, Reiko, Five Years Old, was painted during that realistic phase. The subject is his beloved daughter, Reiko. It’s the very first in a series known as the “Reiko Portraits,” which Kishida continued to paint for years.

Capturing Childhood with Extraordinary Realism

Reiko was only 4 and a half years old when this portrait was made (counted as 5 in the traditional Japanese age system). Getting a small child to sit still must have been a challenge, but the level of detail Kishida achieved is stunning. From the folds of the fabric to the strands of hair, the light in her eyes, and even the trompe-l’œil-style arch in the background—every part of this painting shows his commitment to realism.

His technique recalls that of Albrecht Dürer, the German Renaissance master, whose influence is clearly visible in the precision of Kishida’s brushwork.

This portrait may not just be a father’s loving depiction of his daughter. It could also be Kishida’s personal experiment: an attempt to define what realism truly meant to him.

How Kishida’s Idea of “Real” Evolved

Later in his life, Kishida became more drawn to East Asian art, especially Chinese Song and Yuan Dynasty painting. As a result, his style shifted from strict realism to a more spiritual and stylized expression.

For example, in later works like Reiko Smiling, Reiko’s facial features are more abstracted. Rather than showing her literal likeness, Kishida began portraying her as she existed in his mind and heart.

That’s why Portrait of Reiko (Reiko at Age 5) is so powerful. It marks a turning point—a peak of realism, and a deeply personal moment captured in time. When viewed alongside other portraits in the series, it gives us a deeper understanding of what “real” meant to Kishida throughout his artistic journey.

Collection of Tokyo National Museum

Henri Rousseau, “Liberty Inviting Artists to Take Part in the 22nd Exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants”(1905–1906)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Bold Voice for Freedom in Art

Among MOMAT’s many Japanese masterpieces, this painting by French artist Henri Rousseau stands out. It’s one of the few works in the collection by an international artist—and it’s bold, quirky, and unforgettable.

Rousseau, often called the leader of the “Naïve Art” movement, was a self-taught painter. He worked as a customs officer in Paris and painted in his spare time. In 1886, he began exhibiting at the Salon des Indépendants, a non-juried art exhibition that welcomed all artists. He continued to participate throughout his life.

Though his technical skills were mocked by critics at the time, Rousseau’s bold use of color and imaginative scenes earned him praise from artists like Picasso and Toulouse-Lautrec. His work also influenced Japanese painters such as Tsuguharu Foujita and Shikanosuke Oka.

The Goddess of Liberty Guides Artists Toward Creative Freedom

As the title suggests, this painting shows the Goddess of Liberty guiding artists to the 22nd Salon des Indépendants. She floats above the exhibition hall, with a lion at her feet. A plaque on the pedestal lists the names of important contributors to the show.

The Salon des Indépendants was born as a counter-movement to the conservative art salons of the time. It welcomed every artist equally—no judging, no hierarchy. At first it was seen as radical, but its open-minded approach eventually gained recognition for encouraging freedom and diversity in the art world.

For Rousseau, this exhibition was more than just a show—it was one of the few places where he could be himself. This painting reflects his gratitude, respect, and pride for the movement that accepted him.

Summary: A Place Where Tradition Meets Innovation

This article introduced some of the most iconic works in the collection of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (MOMAT). From Nio(Buddhistguardian) Seizing an Evil Spirit by Hogai Kano to works by Ryusei Kishida, Gyoshu Hayami, and even Henri Rousseau, each piece shows how artists have boldly crossed boundaries between Japanese-style and Western-style painting.

These artists didn’t just preserve tradition. But they weren’t simply trying to break the rules, either. They were always searching for a new kind of expression—something fresh for their time. That spirit of innovation is what gives modern art its lasting energy.

MOMAT is a place where you can quietly experience the traces of those bold artistic experiments. You don’t need to know much about art to enjoy it. Just start by looking—and feeling. You might discover beauty and questions that still resonate with us today.

Visitor Information — The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (MOMAT)

Location: 3-1 Kitanomaru Park, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo

Explore Nearby — The East Gardens of the Imperial Palace

Just south of MOMAT, you’ll find the East Gardens of the Imperial Palace—an oasis of calm in the middle of Tokyo. Opened to the public in 1968, this peaceful garden is part of the old Edo Castle grounds and features lush greenery, seasonal flowers, and historic ruins.

Admission is free, and you only need to go through a simple bag check. You can enter through any of the three gates: Otemon, Hirakawamon, or Kitahanebashimon.

Highlights include the remains of the castle tower, the historic Guardhouse, and the beautiful Ninomaru Garden—perfect for a slow walk after a museum visit. It’s a great way to experience both nature and history in the heart of the city.

References and Sources

Yoshida Akira, Kano Hogai & Takahashi Yuichi, Minerva Shobo, Feb 2006

Tsujii Nobuo, Okubo Junichi et al., Painters of the Late Edo and Meiji Periods, Perikansha, Dec 1992

Haga Toru, The Realm of Painting: Comparative Cultural History of Modern Japan, Asahi Shimbun, Oct 1990

Oshima Art & Literature Archive: The Island That Welcomed the Artists (accessed Nov 10, 2024)

https://torafujii.sakura.ne.jp/gakakanosiron.pdf

Comments