The Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum, opened in April 2005, is one of the most stylish museums in Japan. It is located inside Waterfront Park in Nagasaki City, a refreshing spot where the sea breeze flows through. The building was designed by world-renowned architect Kengo Kuma. Two separate wings stand across a canal, connected by a striking glass corridor on the second floor.

Inside this corridor, you’ll find a trendy café where you can relax between gallery visits while enjoying views of the canal and the city of Nagasaki. On the rooftop, there is an open grassy space with outdoor sculptures. Since both the museum and outdoor areas are freely accessible, it’s also a great place to casually stop by and enjoy panoramic views of Nagasaki Port and Mount Inasa.

Spanish Art at the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum

One of the main highlights of this museum is its outstanding collection of Spanish art. The core of the collection comes from diplomat Yakichiro Suma, making it one of the most important Spanish art collections in Asia.

The Suma Collection

Yakichiro Suma was a prewar Japanese diplomat who served as Ambassador to Spain and held several high-ranking positions in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Cabinet Information Bureau. (Some even say he was involved in secret intelligence activities!)

Beyond his career, Suma was a passionate art lover. During his stay in Spain, he became captivated by Spanish art and collected over 1,700 works, ranging from paintings and sculptures to fine crafts.

After World War II, however, Suma was designated as a Class-A war criminal, which prevented him from bringing most of his collection back to Japan. Years later, his charges were lifted, and after long negotiations, part of the collection was finally returned. Today, 501 pieces are housed at the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum, where visitors can admire them in person.

Interestingly, more than 1,200 works remain in Spain, and research is still ongoing to trace their whereabouts.

Collection Highlights: Spanish Art Through the Ages

When it comes to Western art collections in Japan, the Matsukata Collection at the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo or the Ohara Museum of Art in Okayama are probably the most famous. However, a museum that specializes in Spanish art, like the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum, is quite rare.

Here, centered around the Suma Collection, visitors can explore Spanish art from the 15th-century religious paintings by unknown artists to masterpieces by modern giants such as Picasso and Miró. One of the museum’s biggest attractions is that you can experience the full history of Spanish art in one place.

In this article, we’ll introduce some highlights of the collection in chronological order—taking you on a journey through Spain’s history as seen in its art.

15th Century

Unknown Artist (Aragon or Catalonia School), “Saint Stephen” (late 15th century)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Saint Stephen is known in Christianity as the first martyr. According to the Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament, he was condemned to death by stoning for criticizing Judaism. Because of this story, stones often appear as symbolic elements in paintings of him. In this work, Stephen is shown holding a stone in his right hand and a palm branch—the traditional symbol of martyrdom—in his left.

This painting was created in Spain at the end of the 15th century or the beginning of the 16th century. At that time, religious paintings were often made as part of large altarpieces called retablos, which were installed in churches. These panels acted as “visual stories” to teach the faithful about the lives and martyrdom of saints. This work is thought to have been just one scene from a larger altarpiece that once included other episodes from Saint Stephen’s life.

Hispano-Flemish Style

During this period, Spain was strongly influenced by the realistic painting style of Flanders (modern-day Belgium). That influence is clear in this piece: the use of perspective in the tiled floor, the lifelike textures of the clothing, and the detailed facial expressions. This was a major shift away from the earlier, flatter medieval style toward a more realistic approach.

Because of these features, the painting is often described as Hispano-Flemish style—a blend of Spanish religious sensibilities and Flemish painting techniques. This unique combination became a defining characteristic of Spanish art in the late 15th century.

16th Century

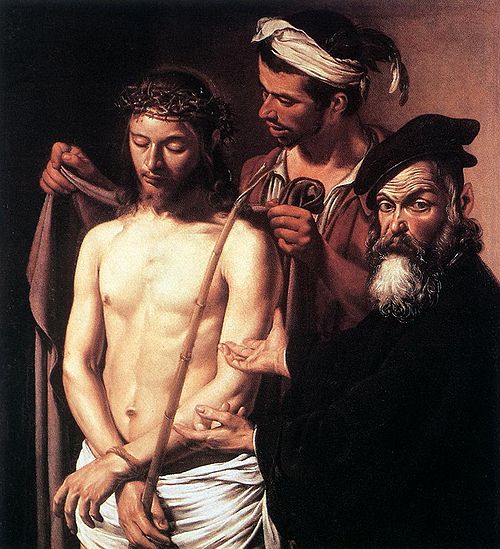

Unknown Artist (Spain), “Ecce Homo ” (late 16th century)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

“Ecce Homo” is Latin for “Behold the man.” The phrase comes from the Gospel of John (19:5), when the Roman governor Pontius Pilate presented Jesus—scourged, crowned with thorns, and humiliated—to the crowd.

This moment is more than a simple scene from scripture. It confronts the viewer with a timeless question: What is human suffering, sin, and salvation? It represents the very essence of Christ’s Passion.

Throughout history, many artists have chosen this theme. Compared to earlier works from the 15th century, this 16th-century painting shows a much more realistic and dramatic style. The depth of space, the arrangement of the figures, and the sense of perspective all add to the scene’s intensity.

Unlike earlier symbolic religious paintings, here we can sense emotions through Christ’s facial expression, gaze, and gestures—as if witnessing a human drama unfold.

The Counter-Reformation Context

This work was created in Spain during the second half of the 16th century, at the height of the Counter-Reformation. During this time, the Catholic Church encouraged art that could speak directly to people’s hearts and strengthen their faith. Themes such as the Passion of Christ, the Pietà, and the Madonna and Child became especially popular because of their emotional impact.

The Ecce Homo in Nagasaki is very much a product of this atmosphere. It has the power to speak directly to the viewer, going beyond being just a religious symbol. It almost feels like faith itself begins in the act of looking at the painting.

17th Century

Unknown Artist (Seville School), “Saint Francis of Paola” (late 17th century)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

From the late 16th to the 17th century, Spain entered its artistic Golden Age (Siglo de Oro). This was the era of great masters like El Greco and Velázquez. In particular, Baroque painting in Spain was known for its realism and its dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), which gave religious art a striking sense of power and spirituality.

One of the most important centers of this period was Seville, in southern Andalusia. Artists such as Velázquez, Zurbarán, and Murillo flourished there, creating a distinct style of religious painting now known as the Seville School.

This painting of Saint Francis of Paola is attributed to a follower of the Seville School, and it reflects the spirit of that time and place.

The Saint and His Miracles

Saint Francis of Paola was an Italian friar and the founder of the Order of Minims. Known for his extremely austere lifestyle, he was also believed to have performed many miracles.

One famous legend tells how he crossed the Strait of Messina by floating on his cloak, as if walking on water. Another story says that when his beloved pet lamb, Martinello, was eaten by a carpenter, Francis prayed over its bones in the furnace, and the lamb miraculously came back to life.

Hints of these miracles can be found in the background of the painting. Yet in the foreground, Francis is portrayed simply as a humble friar in a plain cloak, quietly praying. This contrast highlights his spiritual strength and dignity.

For the people of 17th-century Spain—many of whom could not read—such paintings were more than religious symbols. They were a visual form of storytelling, making the lives of saints and the teachings of faith accessible to everyone.

Unknown Artist (Spain), “Bodegón with Woman and Boy” (17th century)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

The word bodegón may sound unfamiliar. It comes from the Spanish word bodega, meaning “storeroom” or “pantry.” In art, a bodegón is a still life painting that often shows food, drink, or game stored indoors. The genre became popular in Spain during the early 17th century—even among the nobility.

When we think of still life, many people imagine the lavish Flemish paintings of overflowing fruit and grand feasts (see comparison below). But Spanish bodegones are quite different. They are usually simpler and more realistic. This painting, for example, shows a woman and boy preparing game, with naturalistic details of the kitchen and ingredients.

The contrast reflects Spain’s unique religious culture at the time. In Catholic Spain, austerity and modesty were considered virtues. Instead of celebrating luxury, artists depicted humble meals and daily labor. These images carried a quiet moral lesson, reminding viewers of the value of simplicity, faith, and everyday life.

(Collection of The Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum)

18th Century

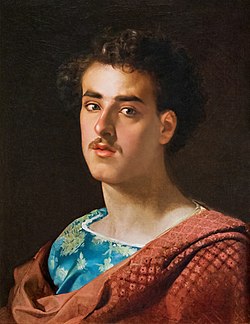

Miguel Jacinto Meléndez (?), “Philip V” (ca. 1708–1715)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

In 1700, King Charles II—the last Habsburg ruler of Spain—died without an heir. The Spanish crown then passed to the French Bourbon dynasty. The first Bourbon king of Spain was Philip V, the young monarch seen in this portrait.

Raised in France, Philip V introduced the elegance and splendor of the French court to Spain. French painters dominated the royal commissions, so it was unusual for a Spaniard to paint an official royal portrait. Miguel Jacinto Meléndez (1679–1734) was one of the few Spanish artists who became a court painter during this time.

This work likely shows Philip V in his late 20s or early 30s. The delicate details of his skin and hair, and the gleaming armor, give the portrait a refined and graceful atmosphere. Compared with the heavier style of 16th-century Spanish painting, this feels lighter and brighter—a clear reflection of French influence.

However, art historians have raised questions. A 1712 portrait of Philip V in hunting attire, housed in the Museo Cerralbo, is considered a confirmed work by Meléndez. While the facial features are similar, the composition and especially the awkward rendering of the right hand in this painting suggest that it may have been produced in Meléndez’s workshop rather than by the master himself.

Either way, this portrait captures a transitional moment in Spanish art, when traditional styles met French-inspired refinement, marking a new chapter in the history of royal portraiture.

Louis-Michel van Loo and Workshop, “King Ferdinand VI and Queen Bárbara” (18th century)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

These two portraits depict King Ferdinand VI of Spain and his wife, Queen Bárbara of Braganza. Ferdinand VI, the fourth son of Philip V, reigned from 1746 to 1759. His rule was marked by efforts to rebuild a stagnant Spain—he strengthened the navy, invested in infrastructure, and reformed the nation’s finances. He also promoted the arts, founding the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, later associated with masters like Picasso and Dalí.

In his final years, tragedy struck. After the death of his beloved wife Bárbara, Ferdinand fell into deep depression and died young at the age of 45. These portraits of the royal couple seem to carry the weight of both their achievements and their sorrows.

For a long time, the works were attributed to the celebrated Neoclassical painter Anton Raphael Mengs, based on a signature. But the timeline did not fit—Mengs only became court painter after both Ferdinand and Bárbara had died.

Today, art historians agree that the portraits were created by Louis-Michel van Loo (1707–1771) and his workshop. The composition is almost identical to Van Loo’s official portrait of Ferdinand VI in the Royal Palace of Madrid. Compared to that version, this painting shows the king with a slightly softer expression. The fine detailing suggests that Van Loo himself may have had a strong hand in its execution, rather than leaving it entirely to his assistants.

19th Century

Francisco de Goya, “The Disasters of War” (1810–1820)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Francisco de Goya is often called “the last Old Master and the first modern artist.” Active in Spain from the late 18th to early 19th century, Goya began as a royal court painter but soon moved beyond tradition to confront the deeper truths of human nature and society.

At that time, Spanish art was mostly religious paintings and portraits of kings and nobles, symbols of power and glory. But Goya used art in a very different way—as a powerful tool of expression.

His most famous example is the print series The Disasters of War, created during the Peninsular War (1808–1814). Instead of heroic victories, Goya showed the brutal reality of war: executions, starving civilians, and endless cycles of violence. These works strip away glory and reveal the human cost of conflict.

The scenes are shocking, even today. Some plates show firing squads and piles of bodies—images that force viewers to face the darker side of history.

Interestingly, Goya never published these works while he was alive. They were too dangerous, criticizing not only Napoleon’s invading French army but also Spain’s restored Bourbon monarchy. The Disasters of War was finally released in 1863, decades after his death.

More than 200 years later, the series is still powerful and relevant. It is not about heroes or lessons learned—it is a direct accusation against war itself. Goya transformed pain, anger, and despair into art, leaving us with questions that remain urgent for our world today.

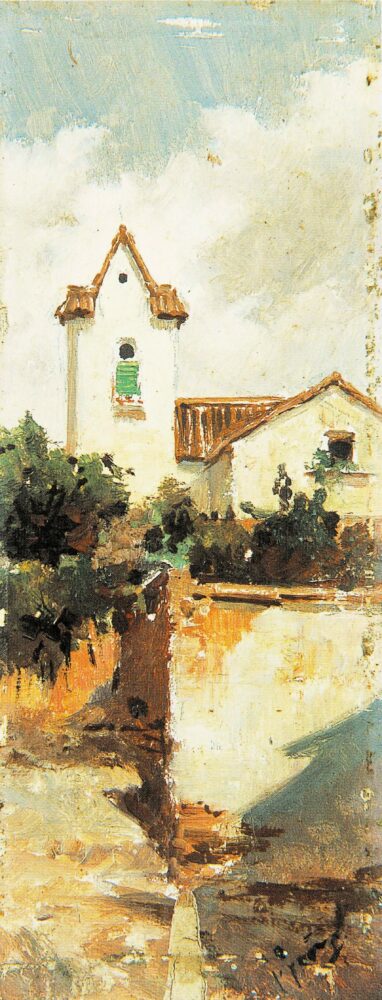

Mariano Fortuny, “Landscape” (late 19th century)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Mariano Fortuny (1838–1874) was one of the most important Spanish painters of the 19th century. His career came after the groundbreaking innovations of Francisco de Goya, who had opened the door for new, more personal forms of expression in Spanish art. Moving away from strict academic traditions, Fortuny embraced a Romantic style that combined emotion, atmosphere, and a love for nature.

Fortuny is best known for his Orientalist paintings, filled with exotic settings and vivid detail. But he was also a gifted landscape painter. This small work—barely the size of a hand—captures a quiet sunlit street corner with delicate, almost poetic brushwork.

Until the 18th century, Spanish painting focused mainly on religious art and royal history scenes, while landscapes were considered “less important.” In the 19th century, however, Romanticism changed that. Artists began to value nature and everyday life as worthy subjects, and Fortuny was among those who helped elevate landscape painting in Spain.

This Landscape was likely painted around 1870, when Fortuny stayed in Granada, southern Spain. Notice the wide expanse of sky, the lightly painted buildings, and the thin layers of color that let the canvas breathe. These touches convey not just a place, but the feeling of light and air at a particular moment in time.

The loose brushwork recalls the style of the French Impressionists, yet the vertical format and sense of space add a lyrical quality beyond a simple sketch. Whether Fortuny painted a beloved corner of the city or just a fleeting view, the work reflects his affection and sensitivity.

Though small in size, this painting shows how Fortuny found poetry in everyday scenery, turning an ordinary street into a timeless work of art.

20th Century

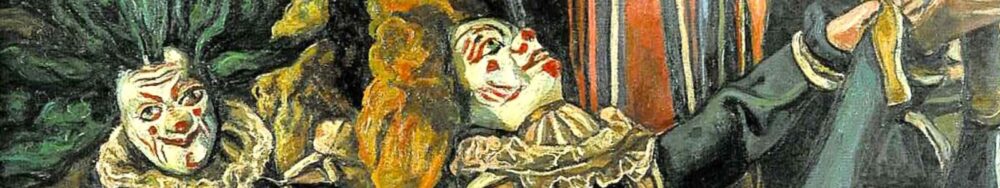

José Gutiérrez-Solana, “The Acrobats” (1930)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

José Gutiérrez-Solana (1886–1945) was one of Spain’s most distinctive painters of the early 20th century. While artists like Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí were revolutionizing modern art in Paris, Solana developed a darker, more introspective vision within Spain itself.

His painting The Acrobats seems at first to show a lively circus scene, with striped backgrounds and colorful costumes. But the figures themselves tell another story. Instead of joy and energy, we see expressionless performers—silent, almost mannequin-like—carrying out their routines with unsettling calm.

This eerie quality is typical of Solana’s style. His characters often look like wax figures or masked dolls, stripped of natural human warmth. They appear alive, yet strangely inhuman, leaving viewers with a lingering sense of unease.

Why did Solana choose this unsettling approach? While there is no clear answer, the year 1930 places the work on the eve of the Spanish Civil War. Spain was entering a period of political and social tension, and the uneasiness of the time may have unconsciously seeped into his art.

The circus is usually a place of joy and spectacle, but in Solana’s hands, it becomes a stage for silence and anxiety. This tension—between the expected brightness and the painted darkness—is what makes The Acrobats such a powerful and unforgettable work.

Conclusion

In this article, we explored highlights from the Spanish Painting Collection of the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum. By following the works in chronological order, you can get a sense of how Spanish art has transformed over the centuries.

Many early Baroque works were listed as “artist unknown,” which actually tells us something important—art was so deeply rooted in daily life that even lesser-known painters had opportunities to create. This shows how essential painting was to Spanish culture.

From religious art that once dominated the scene to the expressive, modern works of the 19th and 20th centuries, Spanish painting evolved alongside society itself. Romanticism inspired by Goya, landscape painting influenced by Impressionism, and Solana’s dark reflections on solitude all reveal the richness and depth of Spain’s artistic journey.

In Japan, visitors often encounter Italian Renaissance or French modern art. But finding such a comprehensive Spanish art collection is rare. That’s why the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum is truly a hidden gem for art lovers.

If any of the works we introduced caught your eye, we highly recommend visiting the museum in person and experiencing their atmosphere up close.

Nagasaki Seaside Park (Mizube-no-Mori Park), located west of the museum

Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum – Visitor Information

Location: 2-1 Dejima-machi, Nagasaki City, Nagasaki Prefecture

Comments