A Private Museum with Masterpieces by Van Gogh and Monet? Menard Art Museum Is More Impressive Than You Think

Have you heard of the Menard Art Museum in Komaki, Aichi Prefecture?

It might surprise you to learn that this quiet museum was founded in 1987 by the husband-and-wife team behind the Japanese cosmetics company Nippon Menard Cosmetic Co., Ltd. — Mr. Daisuke Nonogawa and his wife Misuko. The museum was built to showcase their impressive private art collection.

Today, the museum holds over 1,600 works. The collection spans Western art from the Impressionist period onward, as well as Japanese Western-style paintings and Nihonga (Japanese-style paintings) from the Meiji era to the present. It’s a surprisingly diverse lineup for a museum of this size.

What’s more, you’ll find works by major names like Van Gogh, Rousseau, Monet, and Utrillo — the kind of artists you’d expect to see only in big-city museums. If you love art, you’ll be thrilled by what’s on display here.

Ensor Takes the Spotlight: See His Iconic Masterpiece Up Close

One of the highlights is Self-Portrait with Masks by James Ensor — a bold and unforgettable piece that has become the symbol of the museum. It’s a rare chance to see one of Ensor’s most important works up close.

You’ll also come across paintings by Impressionist and École de Paris artists, quietly lining the galleries. Again and again, you’ll find yourself thinking, “Wait, they have this too?”

Best of all, the museum is far from the crowds of major cities. It offers a peaceful, relaxed setting where you can truly enjoy each masterpiece at your own pace.

In this article, we’ll introduce a few must-see works from the Menard Art Museum collection. So take your time, and enjoy discovering this hidden art spot in Aichi!

Highlights from the Collection

Note: The works introduced here are just a small selection from the museum’s full collection. Some pieces may not be on display during your visit. Please check the Menard Art Museum website for the latest information.

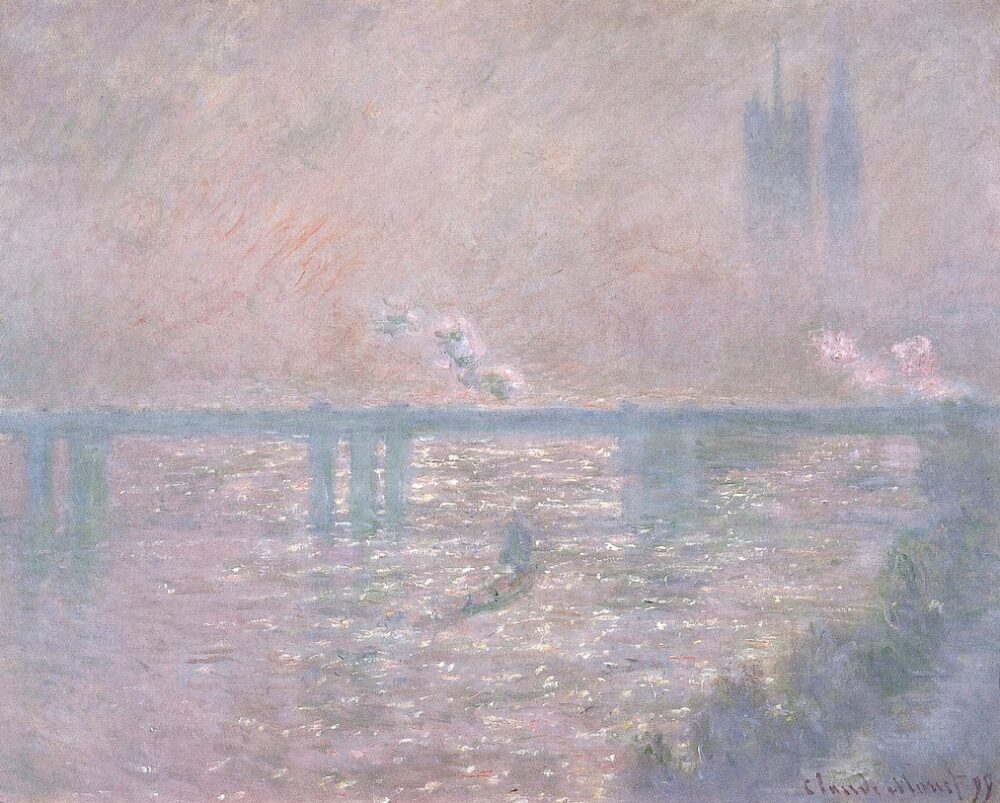

Claude Monet, “Charing Cross Bridge“ (1899)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Claude Monet is one of the most iconic Impressionist painters, known for his famous series like Haystacks and Water Lilies. But this painting, Charing Cross Bridge, isn’t a scene from France—it captures the foggy charm of London.

Monet first visited London in 1870, fleeing the Franco-Prussian War. That brief stay left a strong impression on him, and he returned in 1899. While staying at the Savoy Hotel, he became captivated by the view of the Thames River and Charing Cross Bridge from his window. That’s when he began a new series based on this very motif—eventually painting about 40 versions by 1905.

Monet famously loved London’s fog. He once said:

“I so love London! But I love it only in winter. It’s nice in summer with its parks, but nothing like it is in winter with the fog, for without the fog London wouldn’t be a beautiful city. It’s the fog that gives it its magnificent breadth.”

— quoted in Monet’s Shapes, Denver Art Museum

This soft, hazy painting captures that love perfectly. The way the cityscape melts into the river isn’t just “Impressionist style”—it reflects Monet’s deep emotional response to London’s misty light.

img: by ChrisO

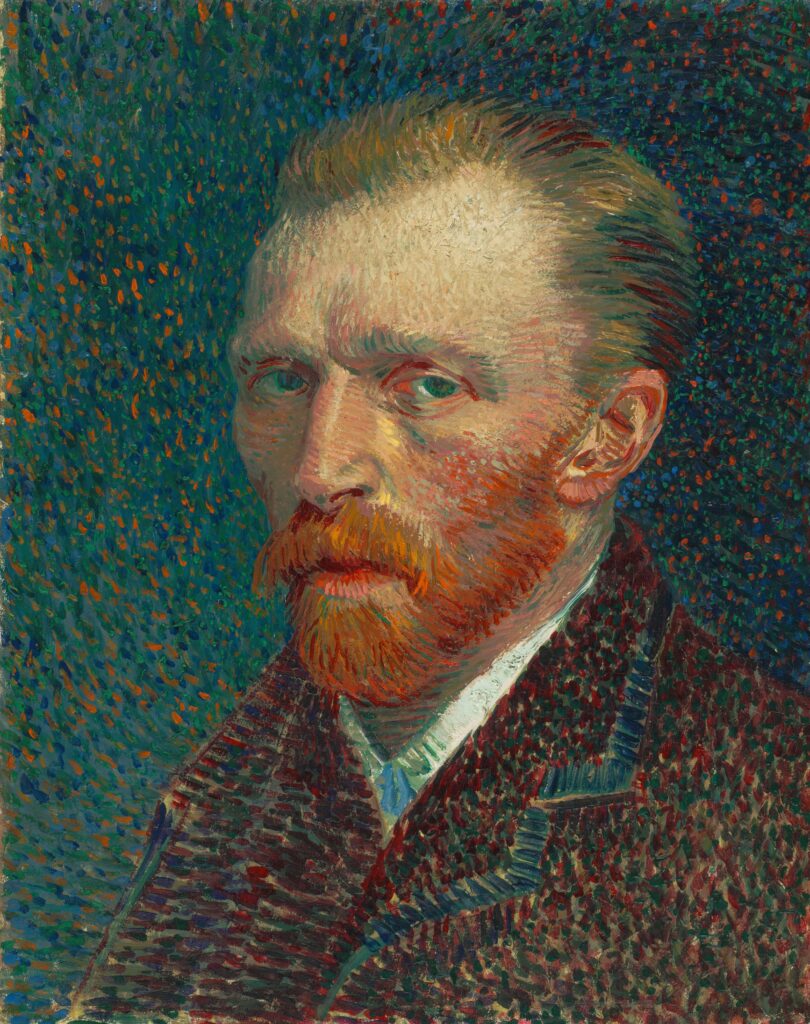

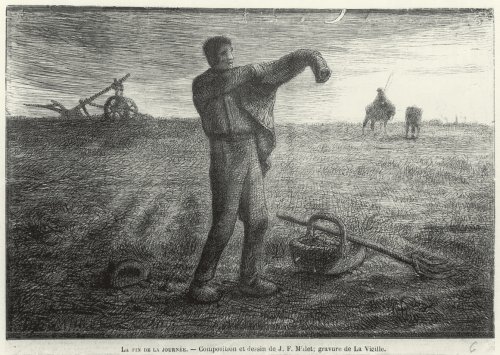

Vincent van Gogh, “Evening – The End of the Day (after Millet)“ (1889)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Vincent van Gogh painted this piece in 1889 while staying at a mental hospital in Saint-Rémy. Though his health was fragile, he never stopped painting.

This work is based on a black-and-white print by Jean-François Millet, a French artist van Gogh deeply admired—especially for his honest depictions of working farmers.

In the painting, a farmer puts on his coat after a long day of labor. It’s a peaceful, humble moment that conveys quiet satisfaction. The dramatic sunset—painted in bold strokes of yellow and blue—is classic van Gogh, full of emotion and contrast.

Van Gogh’s Unique Approach to Reproduction

This painting wasn’t just a simple copy. In a letter to his brother Theo, van Gogh explained:

I find that there’s justification for trying to reproduce things by Millet that he didn’t have the time to paint in oils. […] it’s not copying pure and simple that one would be doing. It is rather translating into another language, the one of colours, the impressions of chiaroscuro and white and black.

— Vincent van Gogh, as quoted in Letter 839, Vincent van Gogh The Letters, Van Gogh Museum and Huygens ING

In other words, he was breathing new life into a black-and-white image through vivid color. Although van Gogh often said he wasn’t good at painting from imagination, this work proves otherwise. He adds his own sense of light, detail, and emotional tone.

By combining Millet’s respect for labor with his own expressive style, van Gogh transformed The End of the Day into something entirely new.

Wood engraving by Jean-François Millet

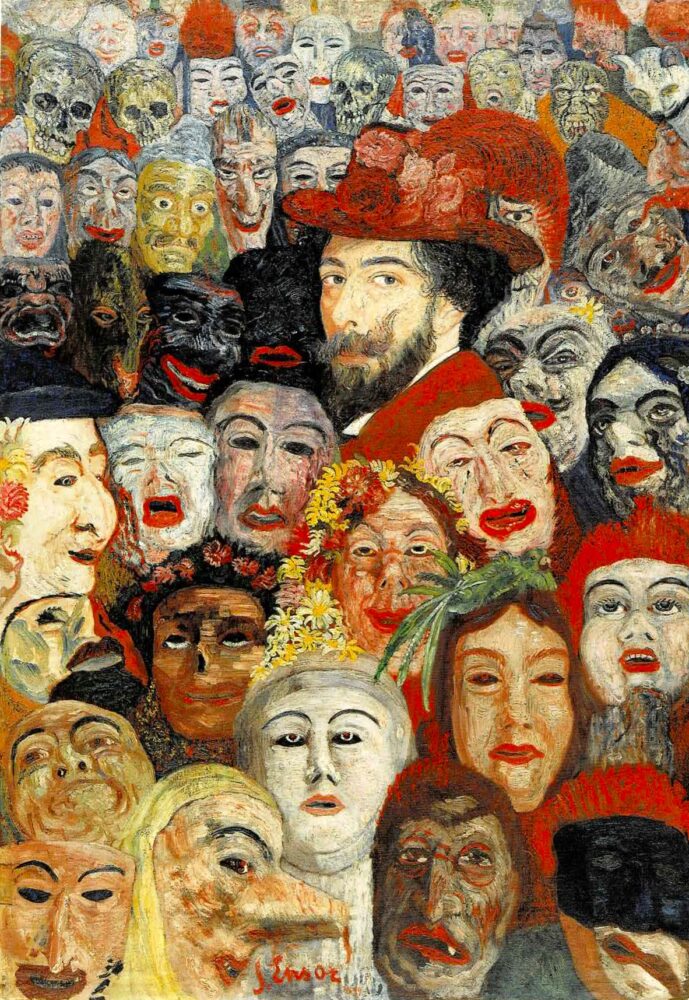

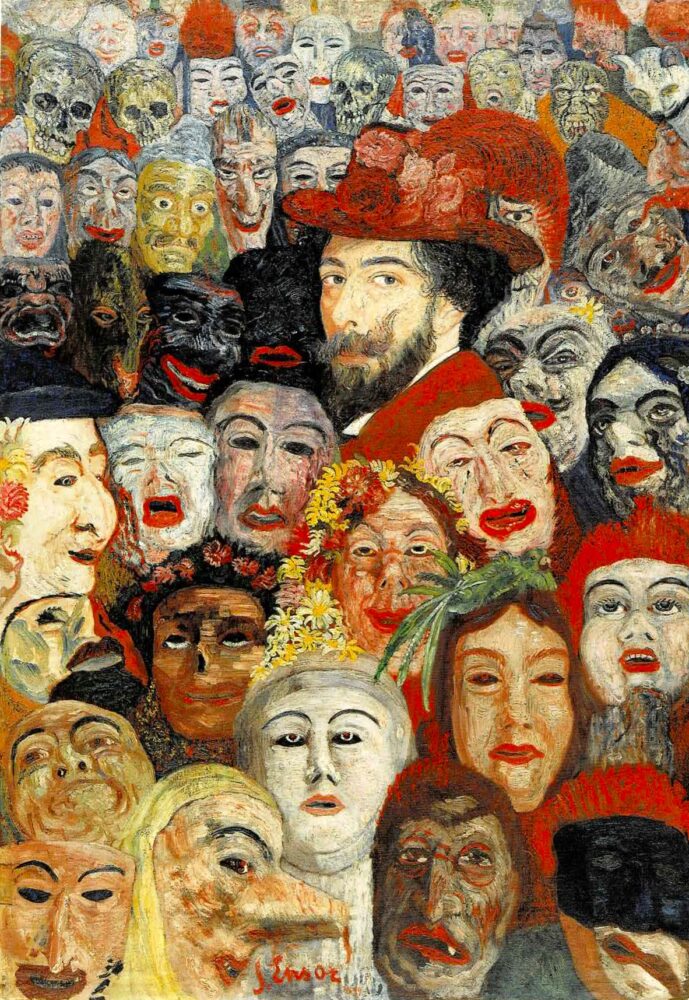

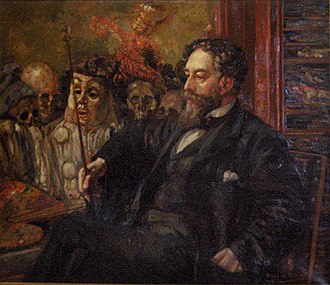

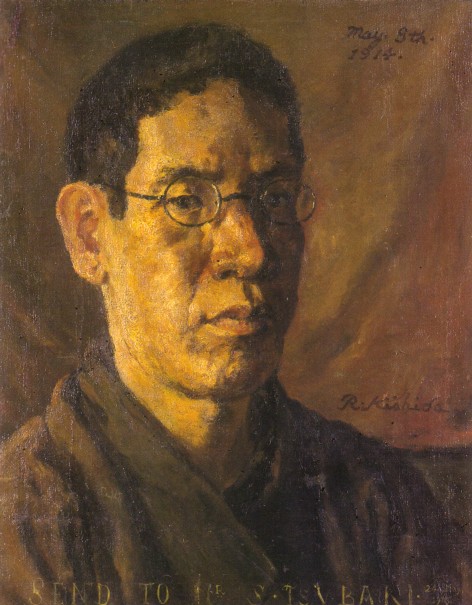

James Ensor, “Self-Portrait with Masks“ (1899)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

The Artist of Masks

James Ensor was a Belgian painter active from the late 19th to early 20th century. He’s best known for his eerie yet unforgettable works filled with masks and skeletons—strange, colorful, and unlike anything else.

His quirky compositions and bold colors were ahead of their time and influenced later movements like Expressionism and Surrealism.

In Self-Portrait with Masks, Ensor stares out from behind a chaotic crowd of masks and skulls. It’s classic Ensor—bizarre, mysterious, and impossible to forget.

What Do the Masks Mean?

This painting was created at the end of the 19th century, a time of rapid industrial and social change. Ensor was part of an avant-garde group of artists in Belgium called Les XX (The Twenty), but even among them, he stood out as an eccentric.

For Ensor, masks may have represented the distance between people, the feeling of being misunderstood, or a satirical look at the vanity and indifference of society. This painting, filled with empty stares and artificial smiles, suggests a world where nothing is quite as it seems.

But there’s another side to Ensor’s masks.

He actually grew up in a souvenir shop that sold carnival masks. So for him, masks weren’t just symbols of criticism or alienation—they were also part of his childhood, full of fun and celebration.

That’s why his paintings, while unsettling at times, also feel strangely festive and warm.

In other words, masks for Ensor were both a way to critique the world and a memory of joy. This tension—between satire and affection—is what makes his art so unique.

What kind of “face” do you see behind the masks?

Henri Rousseau, “Landscape with a Factory“ (ca. 1896–1906)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Strange but Free: The World of Rousseau

“Something feels off—but I kind of love it.”

That’s a common reaction to Henri Rousseau’s art. His paintings often ignore perspective, and the proportions can seem odd. But that very awkwardness gives his work a unique, captivating charm.

Rousseau was a self-taught artist who worked as a customs officer in Paris. He never attended art school and developed his own distinctive style outside of the academic world.

A Lion—or a Dog?

Take a closer look at Landscape with a Factory. The road seems to recede into the distance, yet the people in the foreground and background are nearly the same size. And the animal in the middle? It’s probably a dog—but it’s almost the size of a lion!

But that’s the beauty of Rousseau. He wasn’t concerned with realism or strict rules. He painted what he wanted, how he wanted. That freedom is what makes his art so refreshing.

The Heart of His Art: Freedom

In the painting, smoke rises from factory chimneys, surrounded by a quiet neighborhood. People and animals stroll down the street, creating a peaceful, almost dreamlike atmosphere.

Even though the scale is inconsistent and the perspective is off, the painting draws you in. It reflects how Rousseau saw the world—not as it was, but as he wished it could be.

His work feels nostalgic, a little surreal, and oddly comforting—like a small utopia on canvas.

Rousseau’s lack of formal training didn’t limit him—it freed him.

His paintings remind us that art doesn’t have to follow the rules to be powerful, moving, or beautiful.

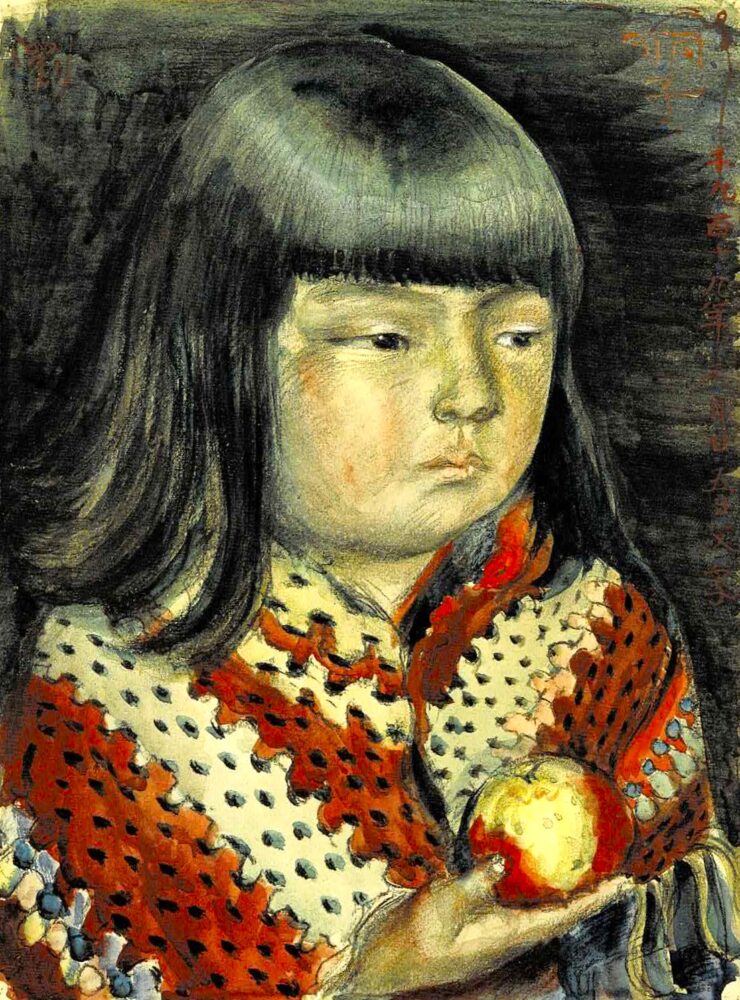

Ryusei Kishida, “Reiko Holding an Apple“ (March 1919)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Small Child, A Powerful Presence

When people think of Ryusei Kishida, one name comes to mind: Reiko—his beloved daughter, and the subject of many of his most striking portraits.

Reiko Holding an Apple is a watercolor from 1919, painted just a year after his well-known work Reiko, Five Years Old (housed in the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo).

In this piece, Reiko holds a shiny red apple and gazes off to the side. Draped over her shoulders is a soft, woolen shawl. Despite being painted in watercolor, the detail is incredibly fine—showing Ryusei’s obsession with realism.

More Than Technique—A Father’s Devotion

Around this time, Ryusei was heavily influenced by Northern Renaissance artists like Albrecht Dürer. Every brushstroke in this piece is deliberate—from the smooth texture of the apple to the woven threads of the shawl and the softness of Reiko’s cheeks.

The most striking detail is Reiko’s face. Ryusei uses delicate cross-hatching to give her features a gentle roundness, capturing both the innocence of a child and the deep affection of a father.

Reiko was not quite five years old when this was painted. Holding a pose must have been difficult—but you can sense her quiet determination to sit still for her father. There’s something very touching about that.

Instead of simply making his daughter look “cute,” Ryusei aimed to show her as she truly was—combining both parental love and artistic seriousness in a single frame.

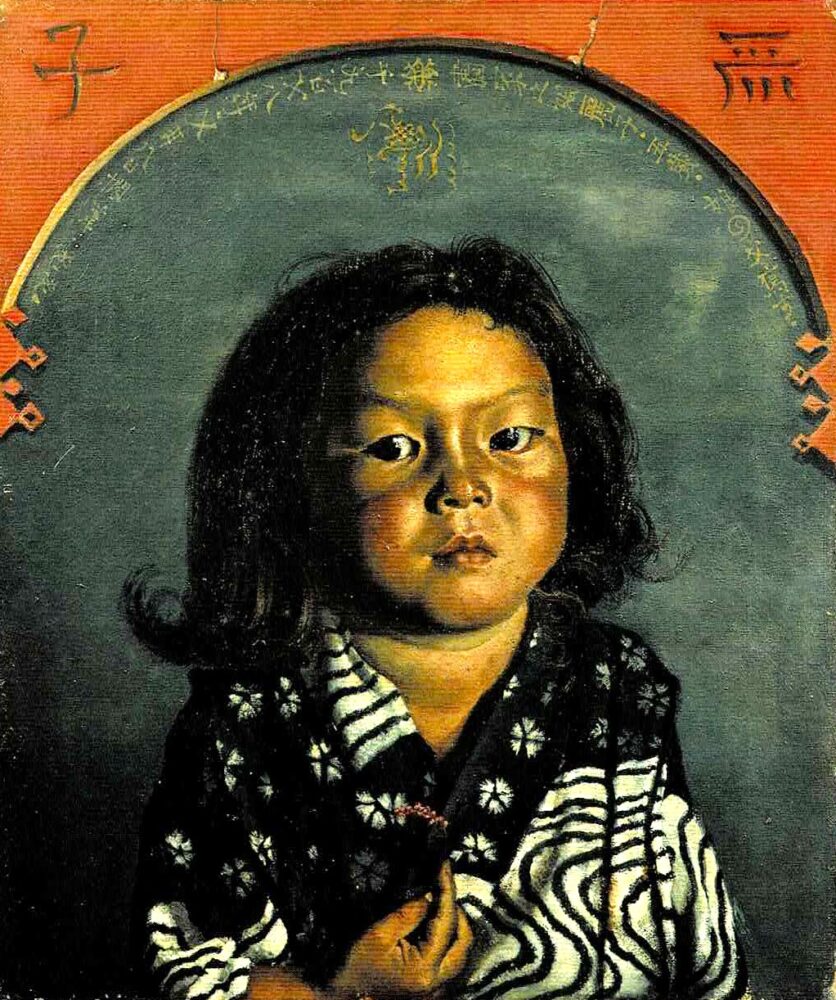

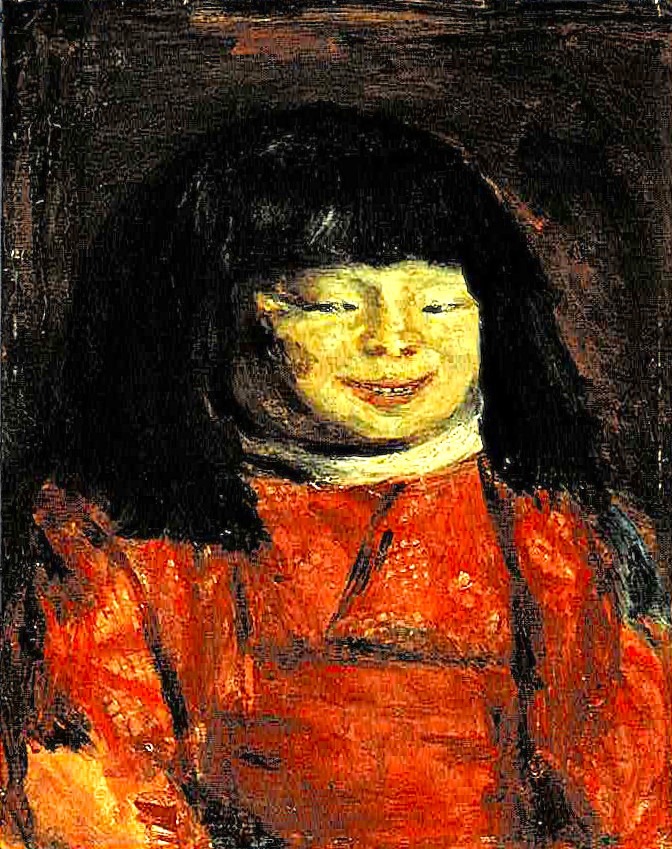

Ryusei Kishida, “Smiling Reiko“ (1922)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Creepy or Captivating?

Reiko and the Mystery of the East

Compared to Reiko Holding an Apple, or even the famous Reiko Smiling (1921, Tokyo National Museum), this painting feels completely different.

In Smiling Reiko, the child’s expression is eerie. She’s smiling—but the smile is unsettling. Still, you can’t look away. The painting has a strange, magnetic pull.

At the time, Ryusei had started to feel the limitations of Western realism. No matter how realistically he painted, something was missing. So he turned his attention to Eastern art, especially its sense of mystery, otherworldliness, and what he described as “derori”—a word he used to express a raw, almost grotesque sense of presence.

The “Derori” Smile

In this painting, Reiko’s face looks slightly distorted, with an unnatural smile. It doesn’t feel innocent—it feels uncanny, like she might not be entirely human.

But that’s what makes the painting so compelling. It walks the line between beauty and discomfort. Instead of copying the surface of reality, Ryusei was searching for a deeper kind of truth.

He called this style “hikinmi” (earthy familiarity) or “derori.”

By intentionally distorting form, he brought out a new kind of realism—raw and emotional, not idealized.

Smiling Reiko (1922) is often thought to be a study for his later painting Rustic Maiden. That makes this piece an important part of Ryusei’s artistic evolution, capturing his experiments with Eastern realism.

This isn’t just another pretty portrait. It shows how deeply Ryusei was struggling to redefine art in his own terms—between tradition, innovation, and personal emotion.

deposited at The Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama

A Museum Where You Can Truly “Talk” to Modern Art

The Menard Art Museum offers an impressive range and depth of modern paintings—so much so that it’s hard to sum up in just a few words.

From Monet’s gentle light, to Ensor’s surreal satire, van Gogh’s quiet intensity, Rousseau’s dreamlike worlds, and Kishida’s pursuit of realism and expression—each piece here presents a different way of seeing and a unique question to ponder.

Despite being a private museum, Menard holds a surprisingly rich and diverse collection of masterpieces. And the atmosphere is calm and quiet—giving you time and space to connect with the art at your own pace.

If you’re visiting the Nagoya area, it’s well worth the short trip to Komaki.

You may find the experience more memorable—and more meaningful—than you expected.

Menard Art Museum – Visitor Information

Location: 5-250 Komaki, Komaki City, Aichi Prefecture

Comments