A Must-Visit Art Museum in Ibaraki for Fans of Western-Style Painting

Located in the scenic city of Kasama, Ibaraki Prefecture, the Kasama Nichido Museum of Art was founded by Jin Hasegawa, the founder of the prestigious Nicho Gallery in Tokyo. Known for its strong focus on Western art, the museum features an impressive lineup of European masters such as Monet, Renoir, Cézanne, Degas, and Van Gogh.

But that’s not all—this museum also showcases iconic works by leading Japanese artists like Tsuguharu Foujita, Yuichi Takahashi, and Ryusei Kishida. From Impressionism to the École de Paris, you can experience the flow of art history all in one place.

Rei Kamoi Room: Step Inside the Artist’s World

Don’t miss the permanent exhibit known as the “Rei Kamoi Room.” Here, works by Japanese painter Rei Kamoi are displayed alongside the very furniture he used, giving visitors the feeling of stepping into the artist’s own studio. It’s an immersive space that brings you closer to the creative process.

The Unique Palette Collection: Where Tools Become Art

Another highlight of the museum is its fascinating Palette Collection, housed in the first floor of the Japan Pavilion. This rare display features actual palettes used by renowned artists like Picasso, Dalí, Sotaro Yasui, and Rei Kamoi.

These aren’t just art tools—some of the palettes are painted with self-portraits or landscapes, transforming them into complete artworks. It’s a one-of-a-kind collection you won’t see anywhere else.

Explore Art Through Architecture and Nature

One of the most unique features of the Kasama Nichido Museum is its layout. The museum is spread out across three separate buildings:

- the Exhibition Pavilion for special exhibits,

- the Japan Pavilion, and

- the France Pavilion, both of which house permanent collections.

To move between these spaces, you won’t walk down sterile hallways—you’ll stroll through beautiful sculpture gardens and a bamboo grove. These outdoor paths are not just a backdrop; they’re an essential part of the museum experience.

Depending on the season and time of day, the gardens show different moods and colors, making each visit feel fresh and inspiring.

Featured Works in the Collection

Note: Some works may not be on display due to loans to other museums.

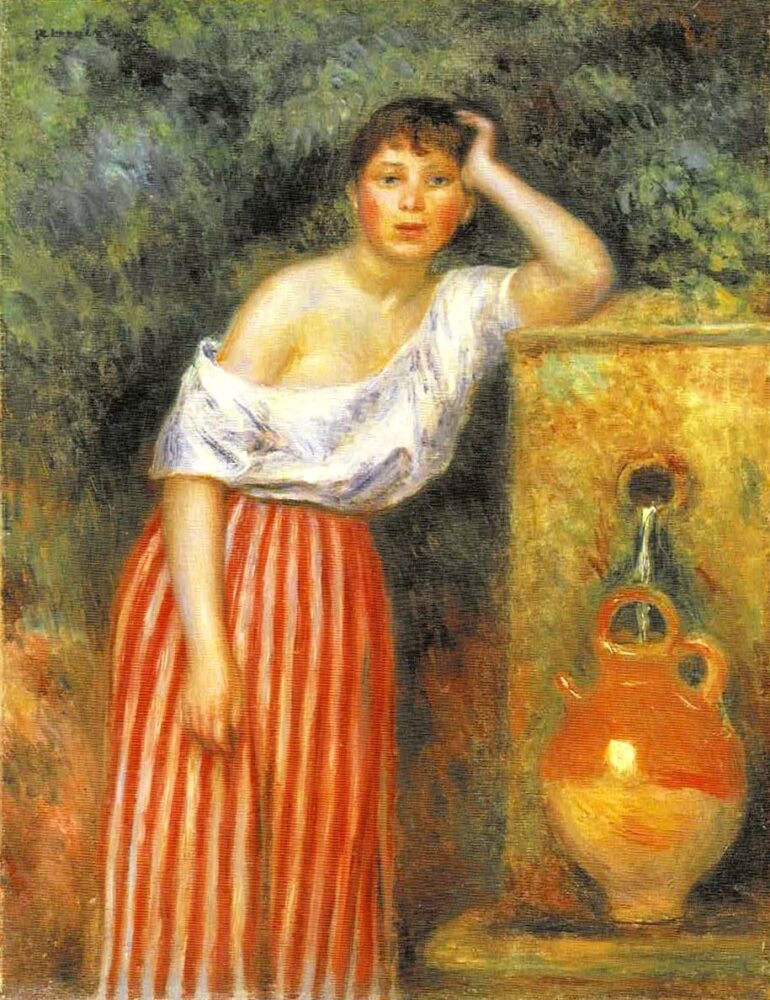

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, “Girl beside a Fountain” (1887)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Style Refined Through Experimentation

Renoir is loved for his warm, light-filled portraits that seem to glow with color. His 1887 painting, “Girl beside a Fountain,” is a perfect example of this charm. The girl’s glowing skin stands out beautifully against the green background, and the whole scene feels crisp and fresh—almost like you can breathe the air in the painting.

Around this time, Renoir was going through a bit of an experimental phase. In his famous work “The Large Bathers” (1884–1887), now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, he tried a more classical style with strong outlines—moving away from the softer touch of Impressionism. His fellow artist Pissarro, however, criticized this change, saying it lost the unity of color.

After this challenge, Renoir painted “Girl beside a Fountain.” The outlines are gentler again, and the figure blends more naturally into the background—a return to the “Renoir” style fans love. Yet the painting still shows a new depth: the textures of the skin, fabric, and pottery are richer and more defined, reflecting Renoir’s growth as an artist.

This work strikes a perfect balance between Impressionism and classicism, showing how Renoir kept exploring and refining his art throughout his life.

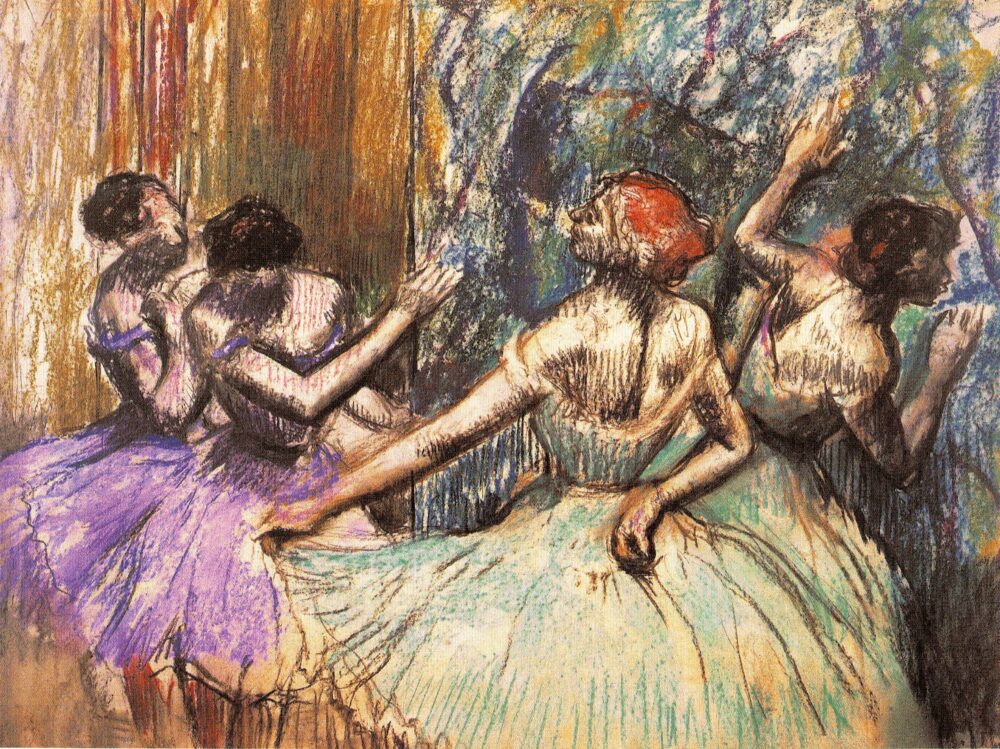

Edgar Degas, “Dancer in the Wings” (c. 1900–1905)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Quiet Moment Behind the Stage

Edgar Degas is famous for his many works featuring ballerinas. But instead of showing grand performances, he often captured small, natural moments—like practice scenes or quiet breaks backstage.

“Dancer in the Wings” is a great example of this intimate point of view. It was drawn when Degas was in his mid-60s and already struggling with poor eyesight. Even so, he continued to create, showing deep dedication to his craft.

At the same time, Degas became more isolated. He took an anti-Dreyfus stance during the Dreyfus Affair, which caused tension with his friends. Despite these personal and social struggles, he remained devoted to his art.

Interestingly, the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum also owns a version of “Dancer in the Wings” with the same composition. This suggests that Degas returned to this image again and again, refining it over time.

An Artist Who Never Compromised

Why would he draw the same composition multiple times? Degas once said:

“Do it again, ten times, a hundred times. Nothing in art must seem to be an accident, not even movement.”

For Degas, art wasn’t about random inspiration—it was about careful observation, repeated practice, and precise planning.

Even as his eyesight failed and friendships faded, Degas never abandoned his method or style. “Dancer in the Wings” shows the quiet passion and relentless drive that defined his life as an artist.

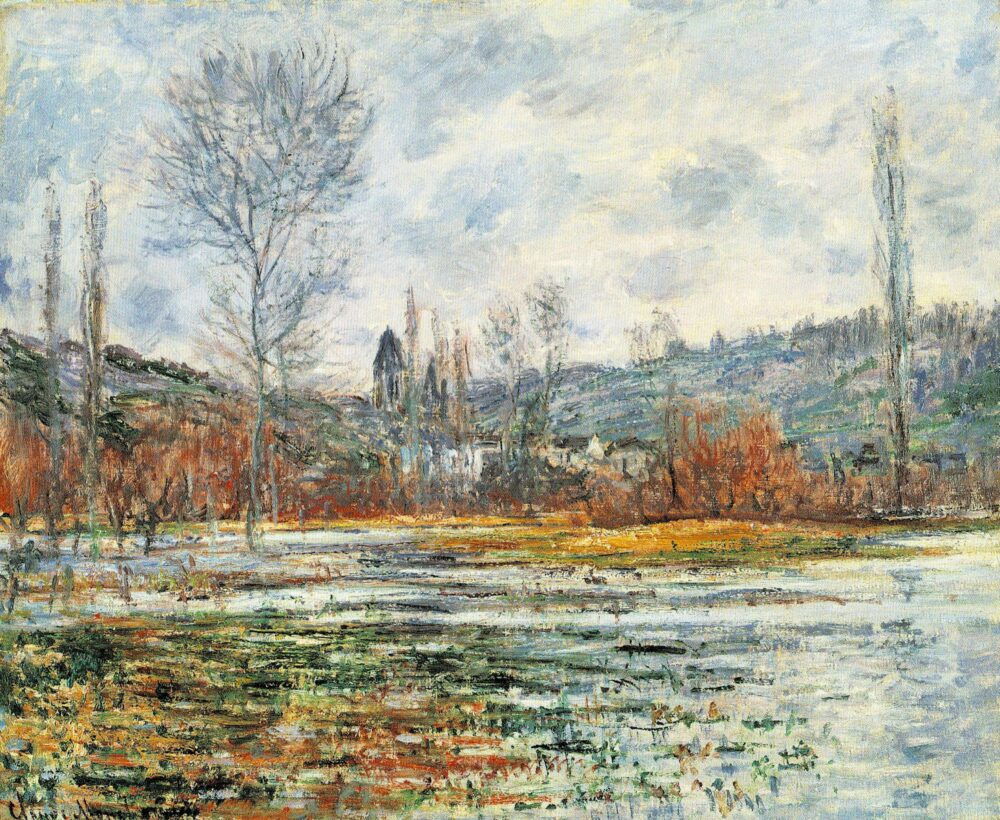

Claude Monet, “Flooded Meadow in Vétheuil” (1881)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Quiet Landscape Born from Personal Hardship

When most people think of Claude Monet, they imagine vibrant scenes filled with light and color—like his famous water lilies or haystacks. But behind those cheerful works, Monet also experienced deep personal struggles.

“Flooded Meadow in Vétheuil” was painted during one of the darkest times in his life. Around 1881, Monet was living in the small riverside town of Vétheuil. His trusted patron had gone bankrupt and even moved into Monet’s home, causing financial stress. To make things worse, his beloved wife Camille fell seriously ill and eventually passed away.

Despite emotional and financial hardship, Monet never stopped painting. This landscape is one of the works created during that painful time.

Quiet Colors Reflect Deep Emotion

Unlike Monet’s usual bright colors, this painting feels subdued. The meadow looks cold and damp, the trees are bare, and the sky is a dull gray. A small town appears in the distance, not lively but lonely. This isn’t just a view of nature—it feels like a reflection of Monet’s inner world.

The painting is quiet and meditative, as if Monet was using his art to process grief and move forward. And he did move forward: the following year, he signed a contract with Durand-Ruel Gallery, gaining financial security. In 1883, he moved to Giverny, where he would later create his iconic water lily paintings.

This painting quietly marks the turning point between the winter of his life and the spring to come.

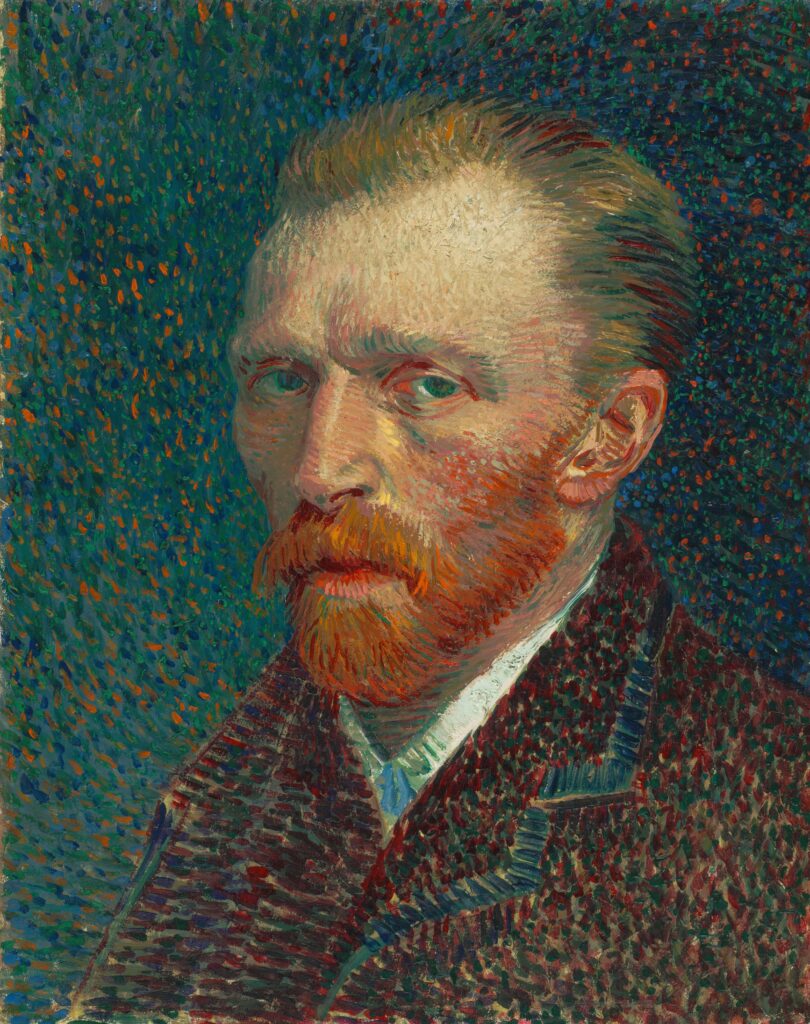

Vincent van Gogh, “Woman on a Road among Trees” (1889–1890)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Path Between Silence and Emotion

This piece, “Woman on a Road among Trees“, was painted while Van Gogh was staying at a psychiatric hospital in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. During this unstable period, he kept painting—perhaps because creating art was the only way he could hold himself together.

This was the same time he produced masterpieces like “The Starry Night” and “Cypresses”. You can see the same qualities here: strong brushstrokes that almost swirl with energy, as if the landscape itself is alive.

Also striking is the use of raw, intense color. While many of his other works from Saint-Rémy use soft, blended tones, this one bursts with pure pigment—almost as if the paint was squeezed directly from the tube. The colors feel intuitive and emotional, creating a sense of urgency and life.

There’s a mix of stillness and tension in this painting. The road doesn’t feel like an ordinary path—it feels dreamlike, even surreal. You might imagine that this is what Van Gogh’s inner world looked like, transformed into a landscape.

Yuichi Takahashi, “Salmon” (1879–1880)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

The Origins of Western-Style Painting in Japan

This realistic painting of a salmon may look simple—but “Salmon” (1879–1880) is a milestone in Japanese art history. It was created by Yuichi Takahashi, one of the first artists to truly bring oil painting to Japan.

In 1873, Yuichi founded a private art school called Tenkai-sha and held monthly exhibitions featuring his own work. Over the next two decades, he produced more than 150 paintings. This version of Salmon, now in the Kasama Nichido Museum of Art, is believed to be the last of three known works on this subject.

At the time, Japanese art was dominated by flat styles like ukiyo-e. Yuichi wanted to paint things that looked real. Using oil paints, he carefully rendered the fish’s slippery texture, glistening skin, and detailed fins. If you look closely, you can even feel the weight and moisture of the salmon.

This painting isn’t just realistic—it’s a bold experiment. Yuichi explored the possibilities of oil painting through a distinctly Japanese lens. When viewed up close, it’s far more than just a picture of a fish. It’s a powerful reminder of where Western-style painting in Japan truly began.

Yoshimatsu Goseda, “Kimono for a Doll” (1883)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Forgotten Pioneer of Japanese Oil Painting

When we talk about the pioneers of Japanese Western-style painting, the name Takahashi Yuichi often comes up first. But another important figure deserves attention: Yoshimatsu Goseda.

Born into a samurai family in the late Edo period, Goseda first studied traditional Japanese painting with his father, Goseda Horyu. He later trained under Charles Wirgman, the British artist who also taught Yuichi. Eventually, Goseda traveled to Paris, where he studied oil painting at its source.

“Kimono for a Doll” (1883) was painted during his time in France and became the first work by a Japanese artist to be accepted into the Paris Salon, a major achievement.

Blending Realism with Japanese Sensibility

Goseda returned to Japan in 1889, but the country was entering a wave of nationalism that made it difficult for Western-trained artists to thrive. Still, when you stand before Kimono for a Doll, those social currents seem to disappear.

The painting shows remarkable technical skill—the soft texture of the fabric, the gentle lighting, and the sense of space all feel incredibly lifelike. And yet, there’s something uniquely Japanese about it: a quiet elegance and calm strength that go beyond realism.

Goseda didn’t aim to simply copy Western art. He embraced oil painting while staying true to his cultural roots, bringing a deep Japanese sensitivity to a European medium.

This work proves that Yuichi wasn’t alone. The roots of Japanese oil painting grew quietly, thanks to artists like Goseda who faced challenges with pride and perseverance.

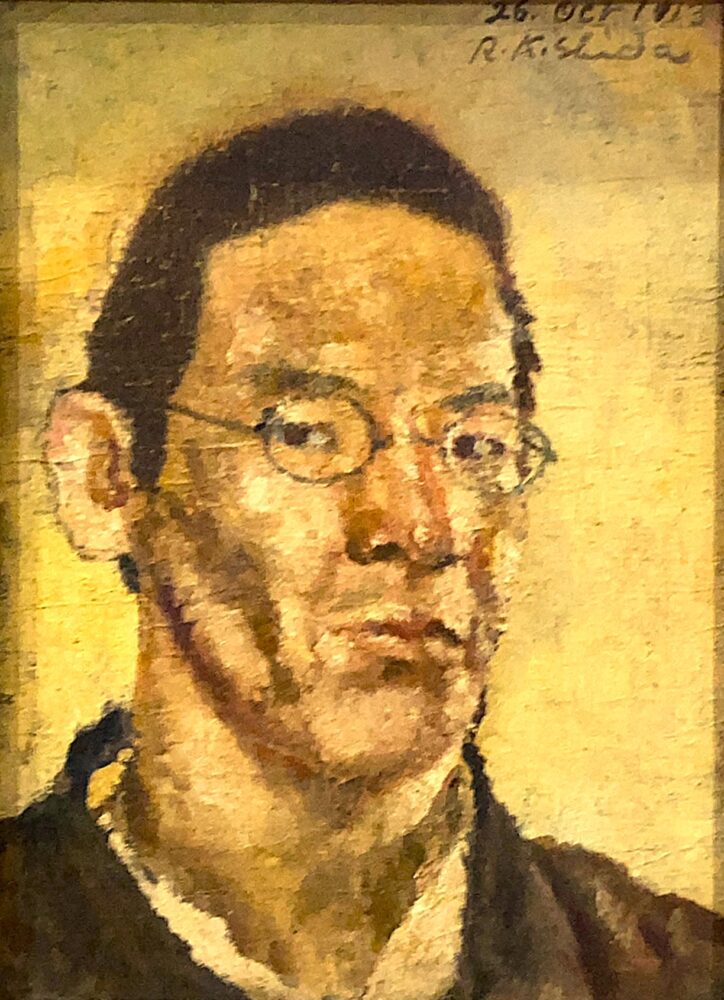

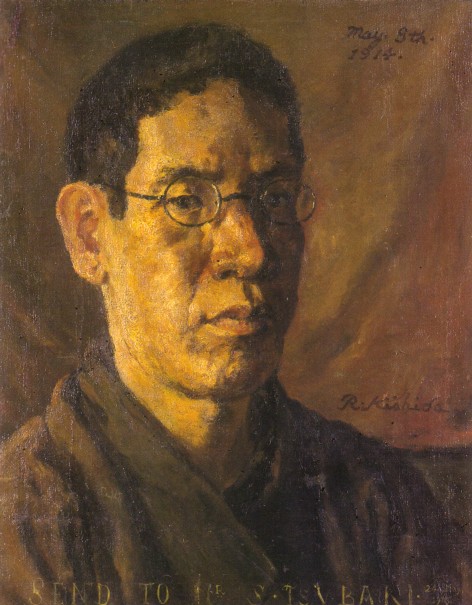

Ryusei Kishida, “Self-Portrait” (October 1913)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Painter Devoted to Portraits

When people think of Ryusei Kishida, they often picture his famous Reiko portrait series. But before his daughter Reiko was even born, he went through a period of painting many self-portraits.

In 1912, still in his early twenties, Kishida was strongly influenced by Post-Impressionist artists like Vincent van Gogh. His early works focused on vivid colors and expressive brushwork. During this time, he became passionate about portrait painting—not just of himself, but also of friends and acquaintances. Some even joked that his obsession earned him the nickname “Kishida the Head-Hunter.”

As he matured, Kishida gradually moved away from Van Gogh’s style and developed a more realistic and classical approach. This 1913 self-portrait is one example of that artistic transition.

You can still see a few bold brushstrokes, but the attention to light and shadow is more refined and natural. Soon after, his work became even more detailed and smooth, following a traditional European technique that left little visible brushwork. This painting reflects a moment of evolution—an artist searching for new ways to express truth through realism.

If you’re curious to see more of Kishida’s portraits, including several of his iconic Reiko paintings, the Kasama Nichido Museum of Art houses an impressive selection that traces his changing style over the years.

A Museum Filled with Quiet Passion

The Kasama Nichido Museum of Art isn’t just a place where famous paintings hang on walls. It’s a place where you can feel the artists’ stories behind each brushstroke.

From Monet’s quiet grief in his flooded meadows, to Degas painting in near-blindness, to early Japanese artists like Takahashi Yuichi and Goseda Yoshimatsu bravely diving into the unknown world of Western-style painting—each piece carries more than just beauty. It holds the spirit of the one who created it.

The museum’s serene layout also helps you reflect deeply. Walkways through bamboo groves and a sculpture garden provide peaceful breaks between gallery spaces, turning your visit into a mindful journey.

This is a museum not just for “seeing,” but for truly feeling art.

Visitor Information – Kasama Nichido Museum of Art

Location: 978-4 Kasama, Kasama City, Ibaraki Prefecture

Things to See Near the Kasama Nichido Museum of Art

Site of the Oishi Residence

Just a few steps from the museum’s Exhibition Pavilion, you’ll find a quiet historical site known as the Oishi Residence Ruins (Oishi-tei Ato).

This spot is connected to Oishi Kuranosuke Yoshio, the famous samurai leader from the classic Japanese tale Chūshingura (The 47 Ronin). It’s said that both his great-grandfather and grandfather once lived here.

Back in the Edo period, this area was the residence of a senior retainer of the Kasama Domain, and to the east lies the ruins of Kasama Castle. The Oishi family lived here for generations—until the local lord, Asano Naganao, was ordered by the shogunate to relocate to Ako, thus beginning the connection to the now-legendary 47 Ronin.

Although no buildings remain, there is a simple informational sign marking the site. It’s a peaceful place where you can pause and get a quiet sense of Edo-period history.

After immersing yourself in the art, why not take a short walk and reflect in this historic spot? It’s a calming way to end your visit.

Comments