Hello again!

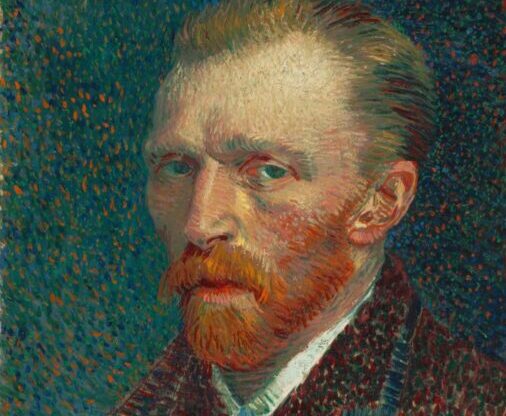

In Part 1, we looked at van Gogh’s early life — how he grew up, dreamed of becoming a pastor, and faced disappointment when that dream fell apart.

This time, let’s move on to the next chapter: his Dutch years.

What were van Gogh’s “Dutch years”?

When people hear the name Vincent van Gogh, most imagine colorful, energetic paintings.

But did you know that for more than half of his career, van Gogh actually painted in dark and earthy tones? Surprising, isn’t it?

The reason lies in his time in the Netherlands.

There, van Gogh studied realist techniques from the Hague School and was deeply inspired by a desire to paint the poor and working people as they truly were.

After losing his dream of becoming a preacher, how did van Gogh decide to become an artist?

And what kind of life did he live while painting in the Netherlands?

Let’s trace that journey together.

Van Gogh Begins His Life as an Artist

A Small Hope Found in Deep Despair

After being rejected as a preacher in the coal-mining region of Borinage, van Gogh fell into deep despair.

Yet, in that darkness, he discovered something new — the act of drawing.

Even during his years devoted to religion, van Gogh never stopped making art.

When he worked at a bookstore in Dordrecht, or when he was studying theology in Amsterdam, he often visited museums to look at paintings.

Art had always been something he needed — a quiet companion in his lonely life.

In Borinage, he began sketching the local miners and their families with pencil.

Later, his former boss from Goupil & Cie, Tersteeg, sent him watercolor supplies, encouraging him to try painting as well.

Still, van Gogh never thought he could make a living from art — not yet.

His brother Theo, who worked as an art dealer, didn’t believe Vincent could become a professional painter either.

Both brothers knew how difficult the art world could be.

In August 1879, when Theo came to visit, he warned Vincent:

“You can’t keep depending on the family forever. It’s time to stand on your own.”

But van Gogh didn’t know what kind of work he could do — and time just kept passing by.

Wandering Through Northern France

In March 1880, van Gogh set out on a wandering journey through northern France.

He had only 10 francs in his pocket — and soon spent it all.

For a week, he walked along country roads, sleeping in abandoned carts or piles of straw at night.

Eventually, he arrived at a small village called Courrières.

Van Gogh later admitted that this journey had “no clear purpose,” yet he secretly carried one wish in his heart —

to meet Jules Breton, a painter he deeply admired.

Van Gogh had met Breton once during his days at Goupil & Cie and had been deeply moved by his paintings.

Perhaps he hoped that meeting Breton might help him find his own path in life.

However—

when van Gogh reached Breton’s house, he couldn’t bring himself to knock on the door.

He later described the building as “cold and unwelcoming,” but it was likely his own shabby appearance that made him hesitate.

In the end, he left Courrières without ever seeing the artist.

It might seem like a failed journey, but something in Courrières changed him.

The scenes he saw there — the haystacks, the brown fields, the clear sky, and the moss-covered roofs —

deeply touched his heart.

Exhausted yet inspired, he made a quiet vow to begin again.

“Well, and notwithstanding, it was in this extreme poverty that I felt my energy return and that I said to myself, in any event I’ll recover from it, I’ll pick up my pencil that I put down in my great discouragement and I’ll get back to drawing, and from then on, it seems to me, everything has changed for me…”1

At this point, van Gogh was 27 years old.

A late bloomer, yes — but from here, his life slowly began to move forward.

Returning to Etten: Conflict with His Father, Theodorus

After his harsh wanderings in northern France, van Gogh returned to his parents’ home in Etten, completely worn out.

His family was shocked by his appearance — thin, pale, and almost unrecognizable.

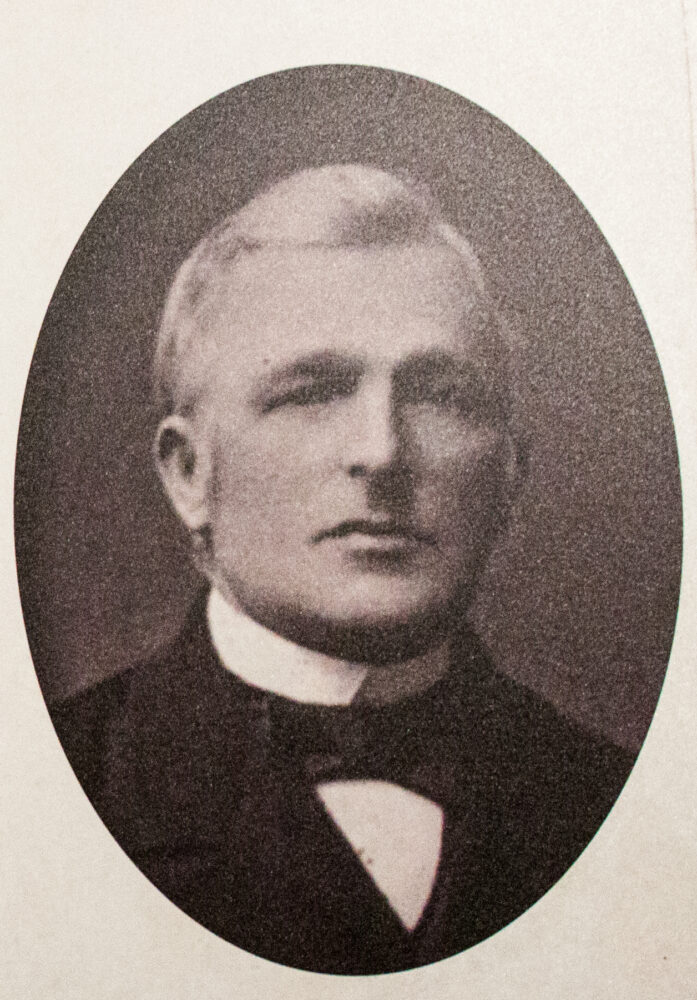

This latest episode, along with his earlier event with Arssen in Zundert and his extreme missionary work in Borinage, made his father Theodorus increasingly worried about his son’s mental health. Eventually, Theodorus decided to have Vincent admitted to a mental hospital in Geel, located south of Etten, and urged him to see a psychiatrist.

Van Gogh refused.

The disagreement turned into a fierce conflict between father and son, and Vincent once again left home for Borinage.

The rejection of his missionary work and the forced hospitalization attempt caused a deep rift in their relationship.

Van Gogh, the Artist

“my torment is none other than this, what could I be good for, couldn’t I serve and be useful in some way… it continually torments me”2

Even after giving up his dream of becoming a preacher, van Gogh never lost his desire to help others through his art.

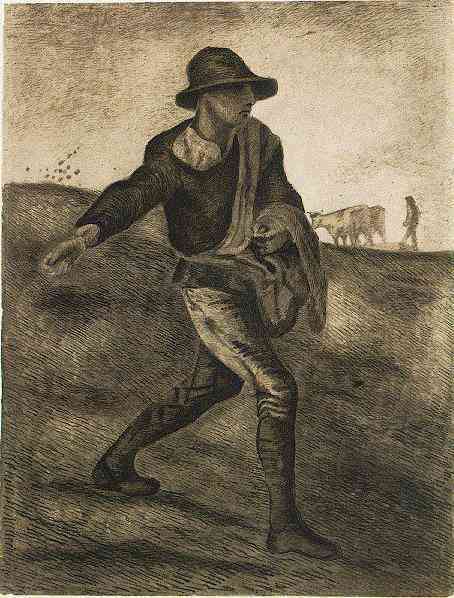

The artist he looked up to was Jean-François Millet, a master of the Barbizon School.

Like Millet, van Gogh wanted to paint the lives of people at the bottom of society — the workers and laborers who were often ignored or oppressed — and reveal their truth to the world.

Through painting, he tried to continue the mission he had once pursued as a preacher.

“everything in men and in their works that is truly good, and beautiful with an inner moral, spiritual and sublime beauty, I think that that comes from God…Try to understand the last word of what the great artists, the serious masters, say in their masterpieces; there will be God in it.”3

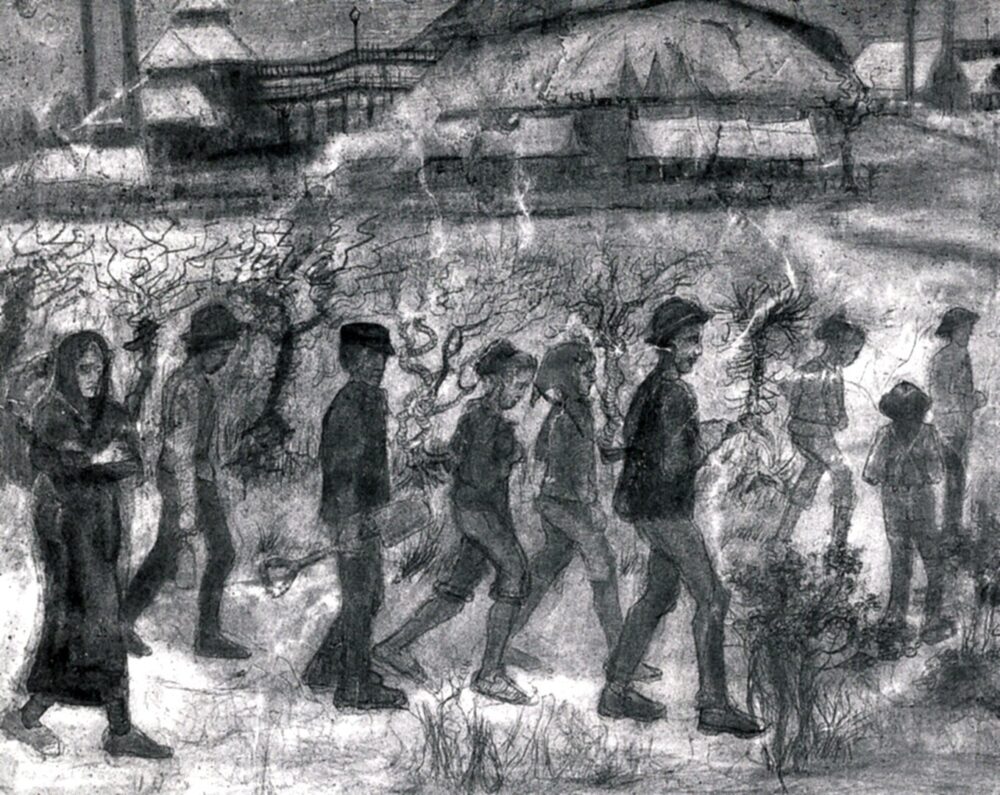

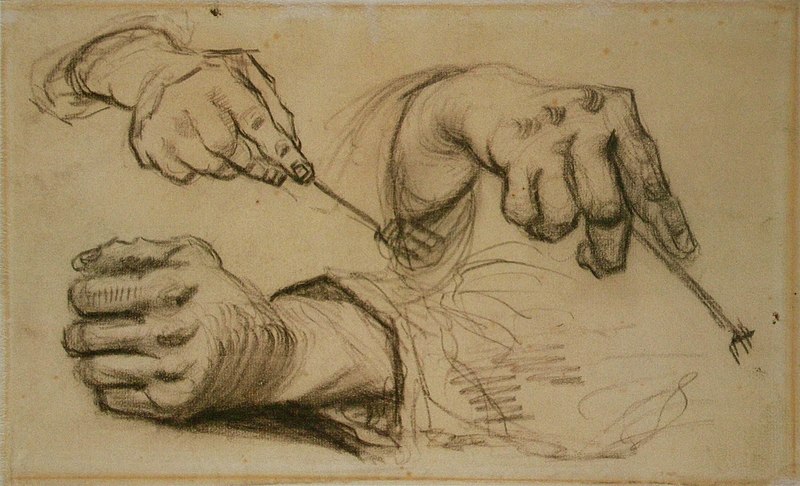

In Borinage, van Gogh spent his days sketching coal miners and their families,

and copying prints by Millet to practice composition and human anatomy.

Finding figure drawing extremely difficult, he wrote to Tersteeg, his former boss, asking to borrow Charles Bargue’s drawing course.

Tersteeg kindly sent not only that but also books on anatomy and perspective.

With his characteristic focus and determination, van Gogh threw himself into his work.

Still, earning a living from art was far from easy.

Although his family urged him to find steady employment, van Gogh refused.

As an amateur painter, he had no income — his works didn’t sell.

Eventually, he began receiving financial support from his brother Theo,

in addition to the help already given by his father.

To Brussels

The Start of Money Troubles

In October 1880, Van Gogh left his small room in the Borinage, declaring that it was “too inconvenient for drawing!” Without even telling his brother Theo, he suddenly headed for Brussels.

But Vincent had no plan. He hadn’t even arranged a place to stay and ended up lodging at a pub and inn called Aux Amis de Charleroi. The rent was 50 francs a month—quite expensive for him—and this marked the start of his “spending spree without a plan.”

Once in Brussels, van Gogh immediately got to work. He visited Mr. Schmidt, the manager of the Goupil & Cie Brussels branch, where Theo had once worked, hoping to be introduced to fellow artists. Schmidt, out of respect for Theo, treated him kindly—but must have been puzzled by the sudden visit of an amateur artist looking for connections.

Meanwhile, Theo was shocked to hear about his brother’s sudden move. “Of all places, why show up at the company like that?” he must have thought, holding his head in disbelief. He quickly advised Vincent not to visit Goupil so recklessly.

What really worried Theo wasn’t just his brother’s usual lack of planning. Deep down, he feared that Vincent’s impulsive actions might once again stir up trouble within the family.

Vincent and His Poor Sense of Money

In Brussels, Vincent van Gogh continued to spend freely. Although he received regular financial support from his family, he began buying not only basic necessities but also a nicer coat and private perspective lessons. Most of all, he spent money on hiring models.

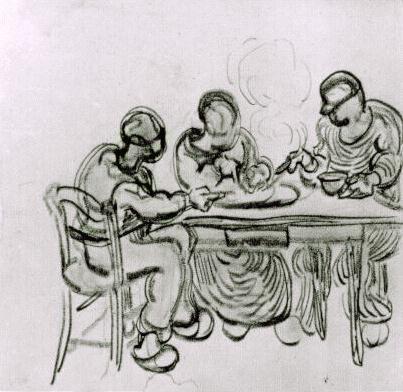

“I have a model almost every day, an old delivery man or some labourer or lad whom I have pose. Next Sunday I’ll perhaps have one or two soldiers who’ll come to pose.”4

At the time, typical art students would start with plaster casts and only move on to live models after a year or more. But Vincent skipped all that—he hired unknown workers as models and drew them right in his own room.

His ambitions went even further. He asked his parents to send extra money so he could build a “wardrobe” of costumes for his models:

“I’ll gradually need a small collection of work-clothes with which to dress the models for my drawings.

The blue smock of Brabant, for example, the grey linen suit that the miners wear and their leather hat, also a straw hat and clogs, a fisherman’s costume of brown fustian and a sou’wester…

This is the only true way to succeed”5

Vincent’s imagination kept growing—and so did his expenses. In January 1881 alone, his father, Theodorus, sent him a total of 60 guilders—about 2 months’ wages for a working-class laborer at the time!

Eventually, even the van Gogh family’s finances began to strain. Theodorus started shifting more of the financial burden onto Theo, who was already successful at Goupil & Cie.

Theo accepted this responsibility out of family duty and continued to support his brother—but this “Vincent support project” would become one of the greatest burdens of his life.

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

A New Friendship — Meeting Rappard

Around this time, van Gogh met a new friend — a young painter named Anthon van Rappard, introduced by Theo as a replacement for Schmidt.

Rappard was born into an aristocratic family and received formal training at the Amsterdam Academy of Fine Arts. Though five years younger than van Gogh, he was calm, kind, and open-minded — qualities that allowed him to get along easily with the often difficult Vincent.

For the lonely van Gogh, Rappard became his first true artist friend. The two quickly bonded and began working together in Rappard’s studio. This friendship soon became one of van Gogh’s most important sources of emotional support.

Conflict with Tersteeg

Meanwhile, van Gogh’s financial troubles continued to grow.

Aside from Theo and their father Theodorus, no other relatives — not even his wealthy uncles Cent and Cor — offered any help. Vincent’s frustration began to boil over.

Could it be that in a family like ours, in which Messrs van Gogh are very rich, and that in the art business, C.M. and our uncle at Princenhage {referring to Uncle Cent}, and in which you and I in the present generation have also chosen that line of work, albeit in different spheres, I say, notwithstanding these facts, could it be that I can’t continue to count in one way or another on those 100 francs a month for the time that must necessarily elapse before I obtain regular employment as a draughtsman? 6

But 100 francs back then was more than a working-class family’s monthly income. His request was, once again, far from realistic.

Desperate, van Gogh also wrote to his former boss, H. G. Tersteeg, asking for support.

What he received in return was a cold and sharp reply:

“You have no right to such a thing.”

Tersteeg harshly criticized Vincent for hiring models and spending money recklessly despite having no experience or reputation as an artist.

He told Vincent to “find another line of work.” At that point, no one outside his family was willing to believe in him or lend a helping hand.

Return to Etten

Friendship with Rappard

In April 1881, 28-year-old van Gogh faced another turning point.

His only friend, Anthon van Rappard, decided to return to his family home, so Van Gogh also left his lodging in Brussels and went back to his parents’ house in Etten.

A few months later, in June, Rappard paid van Gogh a visit in Etten.

The two friends walked together through the nearby fields and marshes, sketching side by side.

Having a fellow artist visit him at his family home must have been deeply moving for Van Gogh, who had spent most of his life in loneliness.

Neighbors later recalled, “That was the only time we ever saw him so cheerful.”

This heartwarming memory of friendship would later inspire his dream of an artist community in the “Yellow House” in Arles, years later in southern France.

Love for a Widow — and Expulsion from Etten

But those peaceful days didn’t last long.

In August 1881, a new storm entered Van Gogh’s heart.

One day, his cousin Kee Vos-Stricker came to visit.

She was the daughter of Reverend Stricker, the same man who had once introduced Van Gogh to the theologian Mendes when he was preparing for the seminary exam.

Kee, recently widowed, arrived at the Etten parsonage with her young son, Jan.

At first, Van Gogh quietly supported her.

But soon he fell in love—and eventually proposed.

Kee, however, firmly refused, saying:

“No, nay, never!“

Most people would have accepted that answer and stepped back.

But Van Gogh was different.

Even her rejection only fueled his passion:

“No, nay, never, what’s the opposite of that? Love on!”7

Naturally, the family was outraged.

His father, Theodorus, scolded him, saying, “You’re tearing the family apart.”

And his uncle, Reverend Stricker, warned him that Kee’s refusal was final.

Still, Van Gogh couldn’t let go.

In November, he even borrowed travel money from Theo to go to Amsterdam and visit Kee’s family home.

But as expected, he was turned away at the door.

When he persisted, Reverend Stricker lost his temper completely:

“Your persistence is sickening!”

Van Gogh’s intensity shocked everyone around him.

At one point, he even held his hand over a flame, saying, “Bring her to me before this hand burns.”

The lamp was quickly blown out—and his desperate act led nowhere.

After this incident, van Gogh’s position in his family home became untenable.

He had no choice but to leave Etten and move to The Hague, seeking help from his cousin, the painter Anton Mauve.

Christmas Farewell

In December, Van Gogh returned to Etten for the first time in a while.

But on Christmas Day, he got into a fierce argument with his father, Theodorus—over something as small as whether or not to go to church.

Years of frustration and pain suddenly erupted.

His resentment from the Borinage days, his anger toward the mission board, almost being sent to a madhouse, and his heartbreak over Kee Vos-Stricker—Van Gogh unleashed it all on his father.

But Theodorus had reached his limit, too.

“Leave my house, the sooner the better, within the half-hour rather than the hour”8

In the end, Theodorus exploded in anger and threw Van Gogh out of the family home in Etten.

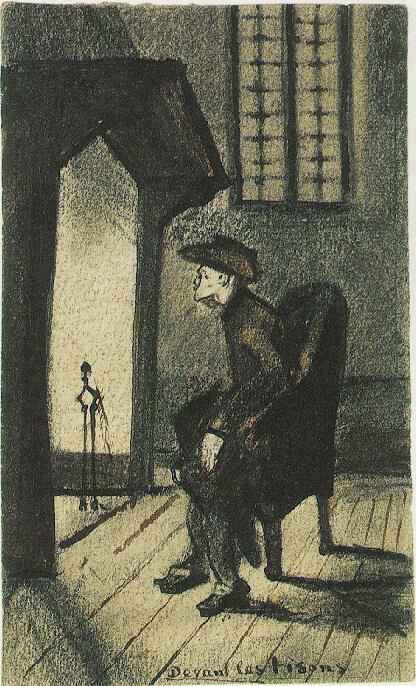

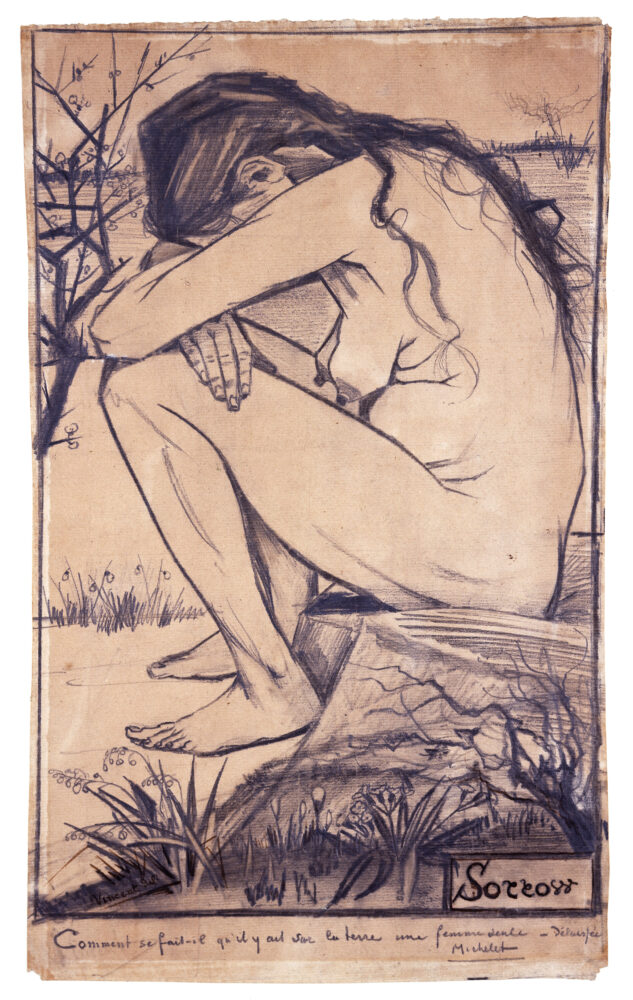

(November 1881, Kröller-Müller Museum)

To the Hague

Escape to The Hague

At the end of December 1881, Van Gogh left his parents’ home after the Christmas dispute and traveled to The Hague, seeking help from his relative, the painter Anton Mauve.

Mauve was a popular artist of the Hague School and was married to Ariëtte Carbentus, a relative on Van Gogh’s mother’s side.

To Van Gogh, Mauve was one of the few trusted mentors who had already built a successful career in art.

Theodorus worried that his son might become a burden to relatives and offered to send him money, but Van Gogh refused.

Instead, he borrowed 100 guilders from Mauve—a considerable sum—and used it to rent a small studio where he could finally work on his art in earnest. Proudly, he wrote to Theo: “I’ve done it!”

However, Theo, furious at his brother’s impulsive actions, didn’t reply for some time.

After spending the money on furniture and art supplies, Van Gogh quickly ran out of funds and wrote to Theo in distress:

“Tell me, Theo, how do I stand with you? Surely you’ve received my last letter … I truly haven’t had a penny in my pocket for a day or two. Of course I’d really counted on your having sent at least the 100 francs for the month of January.” 9

This time, even the usually calm Theo lost his temper:

“but what the devil made you so childish and so shameless as to contrive in this way to make Pa and Ma’s life miserable and nearly impossible? … I assure you that some day you’ll mightily regret having handled this matter so harshly.” 10

Yet Van Gogh refused to apologize.

He insisted he had done nothing wrong, saying he didn’t even have time for regret.

Eventually, he went so far as to threaten to borrow money from Tersteeg, another acquaintance, unless Theo sent funds right away.

“often depend on the money I do or don’t have in my pocket, whether I can set to work at full speed, half speed or sometimes not at all … send the money as soon as possible” 11

And so, Van Gogh’s reckless streak continued to spiral out of control.

Learning from Mauve

(December 1881, Van Gogh Museum)

After finally getting his own studio, Van Gogh began studying watercolor and oil painting under Anton Mauve. Even though Van Gogh had been painting for only about a year, Mauve generously spent time teaching him and encouraged him, saying that “the day will come when you can earn some money on your own.”

Van Gogh wrote with gratitude,

“As far as Mauve is concerned – yes of course I’m very fond of M., and sympathize with him, I like his work very much – and I consider myself fortunate to learn something from him” 12

But when Van Gogh became too passionate about his work, his temper sometimes got the better of him. One day, when Mauve warned him not to touch canvas too much with fingers, Van Gogh snapped back,

“So what? Even if I painted with my heel, as long as it turns out well and gives the right effect, what does it matter?” 13

Later, when Mauve suggested he practice drawing from plaster casts, Van Gogh shouted,

“don’t speak to me of plaster casts any more, because I can’t stand it.” 14

This must have shocked Mauve deeply. Because of Van Gogh’s stubborn and defiant attitude, Mauve gradually began to distance himself.

Meeting Sien — and Breaking with Mauve

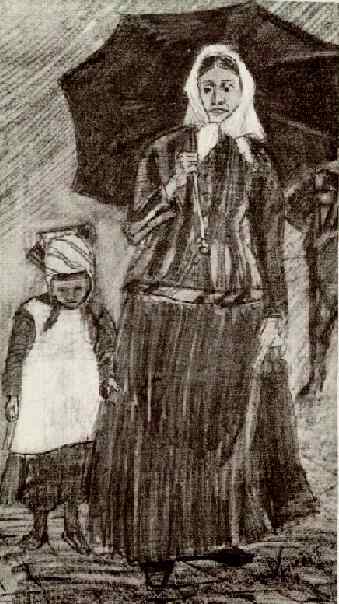

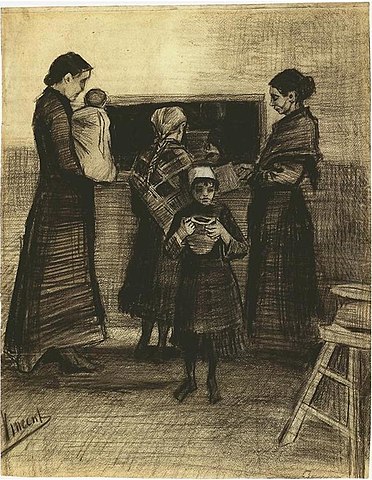

(February 1882, whereabouts unknown)

Just like during his time in Brussels, Van Gogh often invited people he met on the streets to pose as models. That’s how he met Clasina Maria Hoornik, known as Sien, a pregnant woman working as a prostitute.

Van Gogh took pity on her and began supporting her, along with her mother and young daughter.

At the time, society’s prejudice against prostitutes was very strong. And since Van Gogh’s financial help came from Theo’s allowance—not from his own income—he kept Sien’s presence a secret from others.

However, Mauve and Tersteeg, who often visited his studio, quickly realized the situation. Eventually, Mauve stopped contacting him. When they happened to meet on the street one day, Mauve coldly said:

“you have a vicious character”

“‘I certainly won’t come to see you, it’s over and done with” 15

Confession and Threats

At first, Tersteeg—the art dealer who once hesitated to help Van Gogh—still showed some concern for him in The Hague. He occasionally visited Van Gogh’s studio to check on his progress. But once he noticed Van Gogh’s reckless spending and improper behavior, he gave a stern warning:

“I will see to it that you receive no more money from Theo” 16

Realizing he could no longer hide the truth, Van Gogh confessed everything to Theo—about Sien and her family—and pleaded for understanding. What he feared most was that Theo would stop sending him money.

“This winter I met a pregnant woman, abandoned by the man whose child she was carrying … This winter I met a pregnant woman, abandoned by the man whose child she was carrying … you all have my livelihood in your hands, will you leave me penniless” 17

In the next letter, Van Gogh grew defiant:

“I’m not asking you to pay all my expenses. In fact, you can cut down on your support—or even stop it completely… Maybe there are others who would willingly help me make a living.” 18

He then demanded a specific amount—150 francs a month—and declared that he intended to marry Sien. His letter ended with a dramatic warning:

“If I know in advance that you’re definitely going to withdraw your help… I would despair and Christien 〔referring to Sien} and the child would perish… before you strike the blow and chop off my head and Christien’s and the child’s too… sleep on it again.” 19

Appealing to sympathy, anger, and threats—Van Gogh’s emotions were all over the place.

By this time, his relationships with Mauve and Tersteeg had already fallen apart. Theo was the only person left he could depend on. Van Gogh’s letters, swinging between desperation and bravado, reveal just how unstable his mental state had become.

After many heated exchanges, Theo finally gave in. He agreed to increase the allowance to 150 francs a month, allowing Van Gogh to start a new life with Sien and her family in a modest apartment.

(April 1882, Garman Ryan Collection)

Infection and a Visit from His Father

In June 1882, at the age of 29, Van Gogh wrote to Theo from the hospital.

He had contracted gonorrhea—most likely from Sien—and was receiving treatment in The Hague.

” I’m in hospital, although I’ll only be here for about a fortnight. For some 3 weeks I’d been suffering a good deal from sleeplessness and chronic fever, and felt pain on passing water. And now it turns out that I’ve got a very mild case of what’s known as ‘a dose of the clap’.” 20

While Sien and Tersteeg came to visit him, an unexpected visitor appeared—his father, Theodorus.

The two had quarreled the previous Christmas, but Theodorus now showed a wish to reconcile, suggesting that Vincent return to Etten for a short visit after leaving the hospital.

When Van Gogh first arrived in The Hague, he had firmly rejected any financial help from his father.

But now, after his relationships with Mauve and Tersteeg had grown distant, his father’s kindness touched him.

Still, because of his life with Sien, he decided not to go home.

Vincent didn’t tell his father about Sien, yet Theodorus noticed that his son kept glancing toward the door, as if expecting someone he didn’t want his father to meet.

Sensing this, Theodorus asked no questions and quietly left.

Living with Sien and Breaking with Tersteeg

In early July 1882, Van Gogh was discharged from the hospital.

Meanwhile, Sien had given birth to a baby boy at a hospital in Leiden and returned to their apartment in The Hague.

Soon after, Tersteeg came to visit.

Vincent, still filled with the joy of the baby’s birth, expected kind words from his old mentor.

But Tersteeg’s tone was cold.

“What was the meaning of this woman and that child? Where on earth did I get the idea of living with a woman, and with children as well?”

When Van Gogh hesitated to answer, Tersteeg’s anger flared.

“Was I not right in the head? It was obviously the product of a sick mind and body.” 21

It was a painful moment. Tersteeg, who had supported Vincent for years, was deeply disappointed.

As he left, he said one last thing:

“You will make that woman unhappy.”

Theo also criticized Sien, calling her “calculating.”

Even so, Sien named her newborn son Willem, the same as van Gogh’s middle name.

A New Challenge

Two years after he began painting, van Gogh had mostly avoided using oil paints because they were difficult to handle.

Instead, he focused on drawing. But after the troubles with Sien, he realized how important it was to become financially independent.

Hoping to create works that could sell, he started experimenting with watercolors and lithographs.

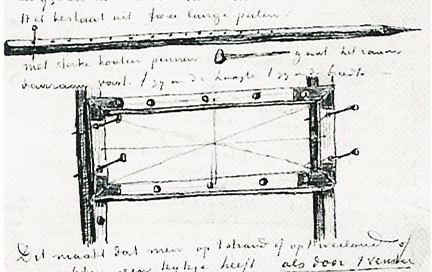

“The result is that on the beach or in a meadow or a field you have a view as if through a window.”

22

(June 1882, watercolor, Private Collection)

(July 1882, watercolor, Private Collection)

Van Gogh was particularly interested in lithography, since it allowed for mass production of images.

However, his technical skills were still limited, and the results did not meet his expectations.

Only a few of his lithographs from this time survive today.

Despite these new efforts, none of his works sold.

(1882, lithograph)

Parting with Sien

Vincent van Gogh and Sien lived together for more than a year, but by May 1883, he began expressing frustration in his letters to Theo.

“Her mood can be such that it’s almost unbearable, even for me, quick-tempered, wilfully wrong, in short, sometimes I despair.” 23

Even so, Van Gogh continued to hire models and focus on his drawings.

After visiting a soup kitchen, he was so moved by the sight that he came up with a bold plan—to turn his studio into a shelter for the poor.

The problem, of course, was money. But Vincent rarely thought in practical terms.

“Now the time must come when we can put even more energy into it. My ideal is to work with ever more models, a whole flock of poor folk for whom the studio could be a kind of harbour of refuge6 on cold days, or when they’re out of work or in need.

Where they know that there are fire, food, drink and a few quarters to be earned. At present that’s only on a very small scale, I hope it will grow.” 24

(March 1883)

At that time, Vincent was living with Sien, her baby, and even her mother—all supported entirely by Theo’s financial help.

Now he was talking about funding a soup kitchen, and Theo had reached his breaking point.

Theo had always done his best to meet Vincent’s constant demands, but his own finances were strained, and his employer, Goupil & Cie, was struggling.

In August 1883, Theo visited Vincent in The Hague and gave him an ultimatum:

if this lifestyle continued, he could no longer send money. He urged Vincent to end his relationship with Sien and rebuild his life.

Theo soon returned to Paris.

Vincent wrote letters full of excuses and emotional appeals, but Theo didn’t give in.

Finally, Vincent made the painful decision to part ways with Sien.

After the separation, Sien left her children with relatives and worked various jobs—seamstress, waitress, and prostitute.

She later married a sailor in 1901, but in 1904, she ended her life by drowning.

To Drenthe

In September 1883, at the age of 30, Vincent van Gogh moved from The Hague to Hoogeveen in the province of Drenthe, more than 150 kilometers to the northeast.

He had once considered returning to his family home in Nuenen (where his father, Theodorus, had been transferred from Etten), but his brother Theo warned him not to go back to Brabant, likely because of the incidents involving Kee and Sien.

Instead, he decided to move to Drenthe, a place that his friend Anthon van Rappard had recommended earlier.

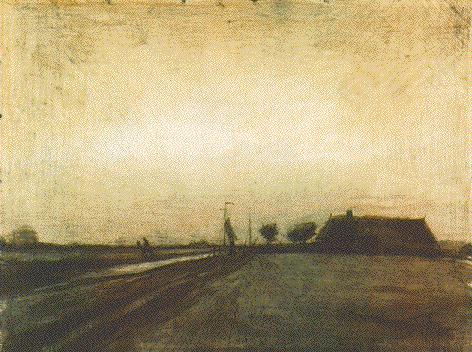

Surrounded by rich nature, Vincent picked up his brush again and began painting with renewed energy.

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

Collection of the Groninger Museum

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

During his stay in Drenthe, Van Gogh mainly painted landscapes and rarely worked on figures. The reason is clearly written in his letters:

“I had some trouble here with models on the heath, where people laughed about it and I was ridiculed and couldn’t finish figure studies that I’d started because of the unwillingness of the models, although I had paid them well, at least for these parts.” 25

Unlike The Hague, where he had contact with people like Sien, Tersteeg, and Mauve, Van Gogh found social life in Drenthe very difficult.

He had no friends there, and even finding a model to paint was a challenge.

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

Feeling increasingly isolated, Vincent began urging Theo to quit his job at Goupil and come to Drenthe so they could paint together. His letters grew more intense, even unrealistic at times:

“We’d have to have, let’s say, 150 francs a month as a minimum, preferably 200.

Credit would have to be found for that, not without a security, but that security would be our work.” 26

In reality, of course, no one was likely to lend money based on the paintings of an unknown artist. Theo never agreed to his brother’s reckless plan.

With his finances running out, van Gogh left Drenthe after just three months.

Even the quiet, natural surroundings couldn’t ease his loneliness.

To Nuenen

Homecoming

In December 1883, Vincent van Gogh left Drenthe and returned to the parsonage in Nuenen, where his parents lived.

You might expect a warm family reunion—but the atmosphere between Vincent and his father, Theodorus, was tense from the start.

Vincent brought up the painful memory of being forced out of the house years earlier and confronted his father:

“he should not have barred the house to me… There wasn’t then, nor is there now any trace, any hint of a shadow of a doubt in Pa as to whether he did the right thing then.” 27

Theodorus, in turn, defended himself:

“I can’t take back anything I did then, I’ve always done everything for your own good, and I’ve always acted on my sincere opinion… did you think I would go down on my knees to you?” 28

The two men argued endlessly, and the mood at home stayed strained for some time.

But after about two weeks, it was Theodorus who gave in.

Vincent had been complaining that, unlike his friend van Rappard, he didn’t even have a proper studio. Perhaps moved by this, his father offered him a small room in the parsonage—previously used as a laundry—to use as his studio.

It was a small but genuine gesture of reconciliation.

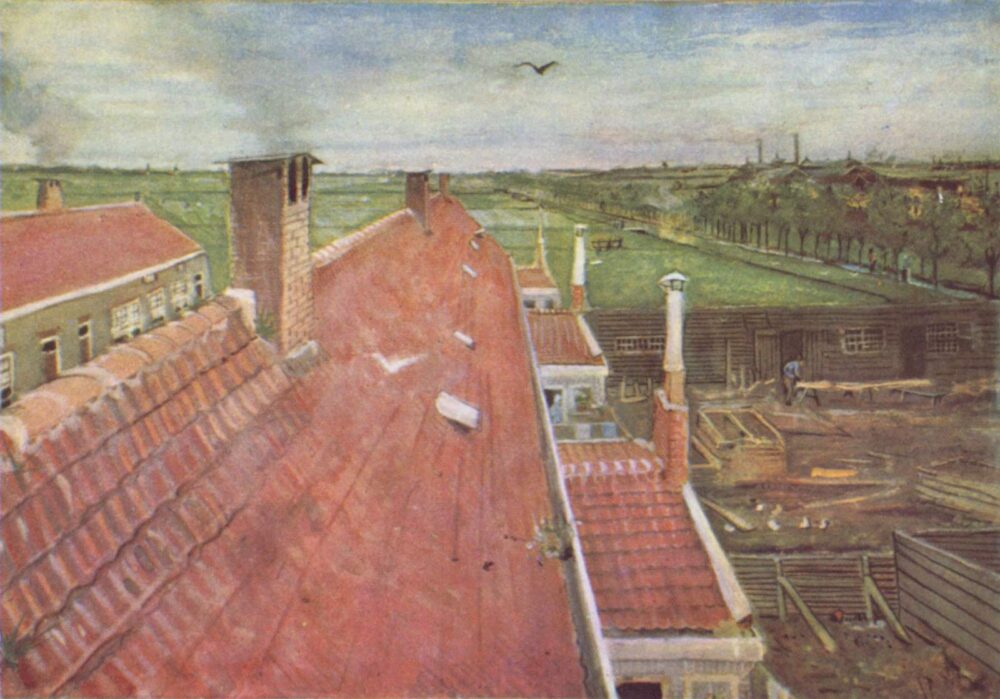

The parsonage is on the left, and Vincent’s studio is in the center.

img: by: A. J. van der Wal

In January 1884, another trial struck the family: Vincent’s mother, Anna, broke her thigh bone after falling while getting off a train in Helmond.

Vincent immediately wrote to Theo to report the accident:

“Something has happened to Ma. Ma hurt her leg getting out of the train.” 29

“I was just on the point of paying off one thing and another with that money you sent. Obviously I’ve now said that since there will be all sorts of extra expenditure for Pa — Pa must go ahead and use it, and the other things will just have to be deferred” 30

“I was glad to be at home in the circumstances, and the fact of the accident naturally having pushed some questions (on which I have a considerable difference of opinion with Pa and Ma) entirely into the background — it’s all going pretty well between us“ 31

Vincent offered Theo’s allowance to help pay expenses and took care of his mother with devotion, even making a stretcher himself in case of emergencies.

This incident seemed to help heal the family’s strained relationship.

However, the problems they were facing were not so straightforward.

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

Bavarian State Painting Collections

The Contract with Theo

When Theo learned that Vincent had quarreled with their father again, he was furious.

In a letter, he harshly called his brother “a pitiful man.”

Vincent fired back immediately, writing a long, emotional letter insisting that it was their father who was in the wrong.

But the argument soon shifted to another topic—money.

Vincent began to blame Theo for his financial troubles, saying that his failure to sell paintings was Theo’s fault:

“You have never yet sold a single thing of mine — not for a lot or a little — and IN FACT HAVEN’T TRIED TO YET. “32

“The money I receive from you is seen first as charity, and second as alms for a poor fool… People ask me at least three times a week, ‘Why don’t you sell your paintings?’ How could anyone live happily in such circumstances?” 33

Vincent then proposed a new arrangement:

“Let me send you my work and you take what you want from it, but I insist that I may consider the money I would receive from you after March as money I’ve earned.” 34

He wanted independence and freedom to create without interference.

From Theo’s point of view, however, the idea was selfish and unrealistic.

Still, refusing Vincent’s request could have made things worse—especially for their aging parents living under the same roof.

So in the end, Theo gave in once again, choosing to support his brother despite the frustration.

The dark tones and lack of color made Vincent’s paintings difficult to sell, especially to Theo, who favored the bright Impressionist style.

Isolation

In the summer of 1884, van Gogh fell in love with Margot Begemann, who had been helping care for his mother, Anna. Their relationship soon turned serious, and they even discussed marriage. However, both families strongly opposed the idea.

The van Gogh family, still traumatized by the earlier affair with Sien, feared another scandal. Meanwhile, the wealthy Begemann family, owners of a linen factory, considered Vincent an odd and troublesome painter—and suspected he was after their money.

In September, devastated by the family’s opposition, Margot attempted suicide by taking strychnine poison. Thankfully, she survived, but her family quickly sent her away to Utrecht to avoid further trouble.

img: by Daan0416

In October, van Gogh’s old friend Anthon van Rappard visited him in Nuenen, and they worked together for a while. But unlike their earlier meetings, this visit ended badly.

By this time, Rappard had gained recognition—he won a silver medal at the London Exhibition and showed his work in several national shows. Vincent, struggling and insecure, couldn’t hide his jealousy. He harshly criticized Rappard’s work, which led to a heated argument and ultimately broke their friendship.

His Parents’ Sorrow

Margot’s suicide attempt quickly became the talk of the town. As rumors spread, not only Vincent but the entire van Gogh family became socially isolated.

At home, Vincent grew increasingly unstable. One evening at dinner, he suddenly flew into a rage and threatened his father, Dorus, with a carving knife.

As van Rappard later recalled:

“In a fit of anger, Vincent grabbed a carving knife and stood up, frightening the old man.” 35

His parents lived in constant fear of his temper. In a letter to Theo, they wrote:

“Vincent is so easily upset… his behavior grows stranger each day… he is consumed by anger and finds no peace. Oh God, help us.” 36

Even Theodorus, once respected in the community, no longer knew how to handle his son’s outbursts. Vincent, in turn, showed no mercy. He even sent Theo an angry letter accusing both his father and brother of betrayal:

“he always called himself my friend nonetheless — the man thought that he was right and simply couldn’t see any differently… one day I spoke out foursquare and said, don’t call yourself my friend if you think this or that of me — people who think of me like that, they’re not friends but enemies“ 37

By early 1885, more than a year after moving to Nuenen, the conflict between van Gogh and his father still showed no sign of ending.

But this bitter struggle would come to an unexpected end—with the sudden death of his father, Dorus van Gogh.

The Death of His Father

On March 26, 1885, Vincent’s father, Theodorus van Gogh, spent the day repairing a fence in the nearby town of Geldrop. Afterward, he had dinner with a friend and even attended a piano recital.

Geldrop was about eight kilometers from Nuenen, and although spring was near, it was a freezing night with snow falling. Despite the weather, Theodorus decided to walk home.

Around 7:30 p.m., the maid at the parsonage heard a noise at the door. When she opened it, Theodorus collapsed into her arms.

He was unconscious. Although they carried him to the living room and tried to save him, it was too late.

The cause of death was thrombosis—it happened suddenly and without warning.

On March 30—Vincent’s 32nd birthday—the funeral was held.

In the past, when faced with the death of Aertsen in Zundert, Vincent had spoken with deep emotion, saying, “It was so beautiful.”

But this time, standing before his father’s sudden death, he was completely stunned and could only stand in silence.

He mentioned his father’s death only briefly in a letter to Theo:

“I felt as you did, in so far as when you write that the work didn’t yet proceed as usual the very first few days, I had the same experience. They have therefore been days that none of us will forget” 38

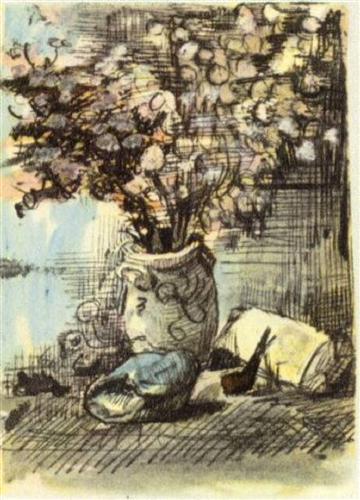

There was just one quiet gesture of remembrance.

Vincent painted a small still life featuring his father’s pipe and tobacco pouch and enclosed it in a letter to Theo.

“the objects in the foreground are a tobacco pouch and a pipe of Pa’s. If you think you’d like it, of course you’re right welcome to have it.” 39

Vincent had always been kind and sincere toward those who were weak or suffering.

He cared for injured miners in the Borinage and tenderly looked after his mother when she was hurt. His compassion in those moments was genuine.

But—

that same kindness did not reach his exhausted father.

Burdened by years of worry—his wife’s injury and his son’s erratic behavior—Theodorus had quietly worn himself down. Vincent, blinded by anger, called him an “enemy” and made no effort to mend their relationship.

By then, no words of apology could undo the pain.

Painting became the only way Vincent could express his sorrow and pay tribute to his father.

A drawing enclosed in Vincent’s letter to Theo, showing his father’s pipe and tobacco pouch.

The Potato Eaters: Van Gogh’s Masterpiece from His Dutch Period

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

The Beginning of an Idea

Let’s go back a bit—to early November 1884.

Vincent van Gogh was feeling restless. He had just learned that his close friend, Anthon van Rappard, had won a silver medal at the London International Exhibition.

Driven by frustration, Van Gogh reached out to two former acquaintances—his mentor Anton Mauve and the art dealer Tersteeg in The Hague. He hoped to repair those broken relationships, believing that reconnecting with two respected figures in the Dutch art world could help his own future.

But both men rejected him.

Still, Van Gogh didn’t give up. Deep inside, his passion for art continued to burn brighter than ever.

A Growing Ambition

A few months later—just three weeks before his father’s death—Theo encouraged him to submit a painting to the Paris Salon.

Van Gogh declined, saying the deadline was too soon. Yet, his reply to Theo revealed his strong motivation:

“Now for myself, I can’t yet show a single painting, not even a single drawing yet. But I’m making studies, and precisely because of this I can very well conceive of the possibility that a time will come when I, too, will be able to compose readily…

I’m thinking about a couple of larger, more worked-up things” 40

He didn’t send a piece to the Salon, but he was already preparing for something far more important—his first true masterpiece.

Painting Real Life

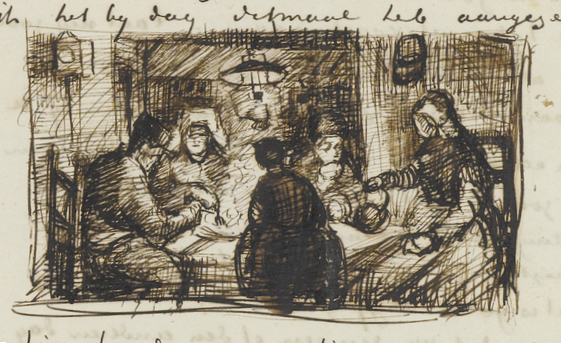

Van Gogh began visiting local cottages in Nuenen almost daily, sketching and observing the farmers at work.

The expressions on their faces, the rough texture of their hands, and the dim light of their evening lamps—all of it inspired him.

For Van Gogh, true art came from everyday life.

This devotion to capturing real people and real scenes would soon lead to his greatest Dutch-period work: The Potato Eaters.

Even If the Colors Are Dark, It’s Still “Real”

In early May 1885, Van Gogh finally completed The Potato Eaters.

Today it’s known as one of his masterpieces from the Dutch period—but at first glance, the colors look dull and heavy. The whole canvas is filled with muted browns and grays, creating a dark, earthy tone.

At the time, his brother Theo, who worked as an art dealer in Paris, often advised him to “make the colors lighter.”

But van Gogh refused to compromise.

“I already know what you say about ‘too black’, but at the same time I’m still not completely persuaded that, to mention just one thing, a grey sky always HAS to be painted in the local tone.”41

He went even further:

“If a peasant painting smells of bacon, smoke, potato steam — fine— that’s not unhealthy — if a stable smells of manure — very well, that’s what a stable’s for… But a peasant painting mustn’t become perfumed.”

“I really have wanted to make it so that people get the idea that these folk, who are eating their potatoes by the light of their little lamp, have tilled the earth themselves with these hands they are putting in the dish, and so it speaks of manual labour and — that they have thus honestly earned their food.” 42

Van Gogh wanted to paint life as it truly was.

A family sitting quietly around the table, eating the food they worked hard to grow—that was beauty, that was reality.

He also thought deeply about color.

In his letters, he quoted Charles Blanc’s Grammaire des arts du dessin, explaining how muted or “broken” colors—like grayish reds and grayish blues—could still create rich harmonies.

So, even though The Potato Eaters might not look bright or colorful, it was an important step in his artistic growth—the first time he truly began thinking about color.

Even Without Recognition

When the painting was finished, Vincent van Gogh sent it to Theo in Paris.

Theo wrote to their mother, saying that “some artists responded positively.” But in truth, he had shown it to only a few people.

Theo himself wasn’t fond of the painting and chose not to exhibit it widely.

Still, Vincent remained proud of his work.

In a letter to his younger sister Wil, written in 1887, he said:

“What I think about my own work is that the painting of the peasants eating potatoes that I did in Nuenen is after all the best thing I did.” 43

And in 1890—just three months before his death—he wrote to Theo:

“I’m thinking of redoing the painting of the peasants eating supper, lamplight effect… I could now make something better of them from memory.” 44

Though he had already mastered bright, expressive colors by this time, Van Gogh still wanted to revisit the dark tones of his early masterpiece.

Sadly, the remake never happened—only a rough sketch remains.

Throughout his ten years as a painter, van Gogh’s style changed dramatically.

Yet The Potato Eaters was the one work he always held close to his heart—his first true masterpiece, born from struggle, honesty, and conviction.

It may be dark and rough, but within that darkness lies the very essence of Van Gogh’s art and spirit.

Separation from Friends — and from His Homeland

The Break with Anthon van Rappard

When making lithographs, the image is reversed during printing, but van Gogh seemed unconcerned about this technical detail.

In May 1885, Van Gogh created a lithograph version of The Potato Eaters and sent it to his friend Anthon van Rappard.

The reply that came back, however, was nothing like what he had hoped for—it was harsh, even cruel.

Rappard wrote:

“You’ll agree with me that such work isn’t intended seriously. You can do better than this — fortunately; but why, then, observe and treat everything so superficially? Why not study the movements? Now they’re posing… why may that man on the right not have a knee or a belly or lungs?… why must the woman on the left have a sort of little pipe stem with a cube on it for a nose?

And with such a manner of working you dare to invoke the names of Millet and Breton? Come on! Art is too important, it seems to me, to be treated so cavalierly.” 45

The words were brutal. Predictably, Van Gogh was furious.

He sent the letter back and wrote a long, indignant reply.

“That I don’t care about the form of the figure, which you’ve said before — it’s beneath me to take any notice of it and — old chap — it’s beneath you to say something so unfounded… I know of no drier friendship than yours… If you want to break with me — very well.” 46

After further exchanges, Van Gogh sent what amounted to a final ultimatum:

“Either cordial or over.

So there you have my final word. I want you to come right out and take back once and for all, without reservation, what was in your last letters — beginning with the one I sent back to you…

you take back everything in those letters, we can begin the friendship anew” 47

But Rappard did not respond.

Van Gogh had issued such “ultimatums” many times before—to his brother Theo, who always forgave him and continued to support him.

Rappard, however, was not bound by blood. Unable to tolerate Vincent’s forceful demands, he chose silence.

Their friendship ended there.

Leaving the Netherlands

In July 1885, when Vincent van Gogh was 32, a decisive event occurred.

Gordina de Groot, one of the models for The Potato Eaters, was discovered to be pregnant.

Suspicion immediately fell on Van Gogh, who often visited her family’s home.

His reputation in the village had long been poor. Ever since the scandal involving Margot Begemann, people viewed him as a troublesome outsider—the “crazy painter.”

Though the rumor could not be proven, it was damaging enough.

The local Catholic Church issued an order forbidding its parishioners from modeling for Van Gogh.

With that, he lost the very means to continue painting people.

Making matters worse, his relationship with his family deteriorated after the death of his father, Theodorus.

He no longer lived with his mother and sisters. His sister Anna later recalled:

“He did whatever he pleased, upsetting everyone. Father must have suffered greatly because of it.” 48

Frustrated and worried for their mother, Anna demanded that Vincent leave home.

Finally, he decided to depart from Nuenen.

Before leaving, van Gogh visited a friend, Anton Kerssemakers, and left behind a small landscape study of autumn trees.

When Kerssemakers noticed that it lacked a signature and asked why, Vincent replied:

“Perhaps I’ll come back someday. But for now, there’s no need to sign it. Later, people will recognize it as mine—and when I’m dead, they’ll write about me. While I’m alive, I’ll just keep working toward that.” 49

With those words, Van Gogh left Nuenen in November 1885.

He still hoped that one day he might reconcile with his family and live together again.

But that day never came.

Vincent van Gogh would never set foot on Dutch soil again.

Collection of the Kröller-Müller Museum

Summary: The Dutch Years

After giving up the path of a clergyman, Van Gogh chose a new calling — to live as an artist.

When we think of Van Gogh, we often imagine his bright, colorful paintings filled with energy and emotion.

But at the beginning of his artistic journey — during these “Dutch Years” — his works were dark, somber, and earthy in tone.

They were very different from the vivid style he would later become known for.

Behind this style lay his admiration for the Barbizon school, especially for Jean-François Millet.

Van Gogh deeply respected Millet’s way of depicting the lives of peasants.

Like him, Vincent wanted to paint the dignity of humble, hardworking people — and that desire gave rise to his muted, shadowy color palette.

Still, his technique was not yet on par with masters like Millet or Jules Breton.

And his style, neither academic nor impressionist, failed to impress his brother Theo.

Theo advised him to “paint brighter, more like the Impressionists,” but Vincent refused to change his approach.

Even his major work, The Potato Eaters — the passionate culmination of five years of effort — did not move Theo as much as Vincent had hoped.

Yet, during this period, Van Gogh discovered color theory, especially the writings of Charles Blanc.

He began to see subtle harmonies even within dark tones, developing the sensitivity to color that would later define his art.

These early years were, in a sense, the roots of the Van Gogh we know today — the painter who found poetry in color and light.

And so, the story moves on to the next chapter.

In the sunlit town of Arles in southern France, how would his art transform?

Continue to Part 3: The Arles Period.

Sources

- Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 158, Cuesmes, Friday, 24 September 1880, in The Letters of Vincent van Gogh, ed. Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2009). https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let158/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 155. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let155/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 155. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let155/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 162. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let162/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theodorus van Gogh and Anna van Gogh-Carbentus, letter 163. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let163/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 164. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let164/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 180. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let180/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 199. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let199/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 198. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let198/letter.html ↩︎

- Theo van Gogh to Van Gogh, letter 197. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let197/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 200. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let200/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 199. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let199/letter.html ↩︎

- Translated by the author from Shiro Futami, trans., The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, vol. 4 (Tokyo: Misuzu Shobo, 1984), p.1250, quoting Kerssemakers, A. (1930, October 10). Herinneringen aan Vincent van Gogh [Reprint of original work published 1912]. Eindhovens Dagblad ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 219. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let219/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 224. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let224/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 221. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let221/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 224. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let224/letter.html ↩︎

- Futami, trans.,The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, vol. 2, p.473 ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 227. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let227/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 237. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let237/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 247. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let247/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 254. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let254/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 342. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let342/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 334. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let334/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 388. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let388/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 396. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let396/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 410. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let410/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 411. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let411/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 423. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let423/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 425. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let425/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 428. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let428/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 432. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let432/letter.html ↩︎

- Futami, trans.,The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, vol. 3, p.1054 ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 422. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let422/letter.html ↩︎

- Translated by the author from Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith. Van Gogh: The Life. Translated by Kazuya Matsuda, vol. 1, Kokusho Kankokai, 2016, p.428 ↩︎

- Naifeh and Smith (2016), P.428 ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 473. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let473/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 489. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let489/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 490. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let490/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 485. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let485/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 450. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let450/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 497. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let497/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Willemien, letter 574. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let574/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 863. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let863/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 503. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let503/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 514. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let514/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 517. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let517/letter.html ↩︎

- Naifeh and Smith (2016), P.457 ↩︎

- Futami, trans.,The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, vol. 4, p.1250 ↩︎

Comments