Located in the city of Abashiri, surrounded by the vast natural beauty of Hokkaido, the Abashiri Prison Museum is an open-air history museum that preserves and displays real prison buildings from Japan’s Meiji era.

More than just a tourist attraction, the museum tells the powerful story of how prisoners were forced into harsh labor to help develop Hokkaido’s wilderness. This deep historical background also makes the site an important piece of Japan’s cultural heritage.

A Prison Museum? What Kind of Place Is It?

In recent years, “Abashiri Prison” has gained attention as the setting for movies and manga.

However, the Abashiri Prison Museum is different from the modern Abashiri Prison, which is still in operation today. Since the 1980s, valuable historical buildings from the old prison have been relocated here and carefully preserved for the public.

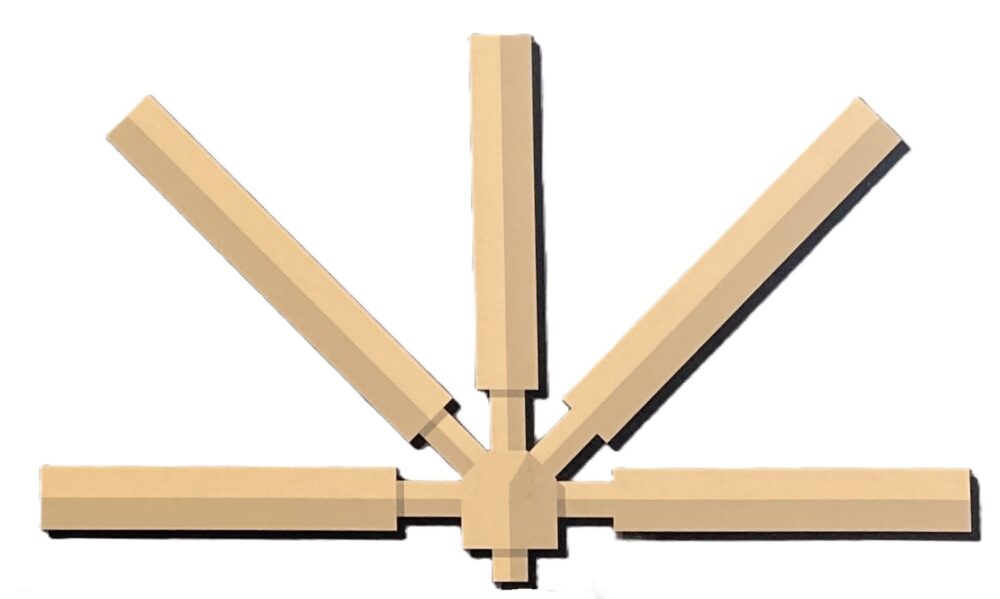

The main attraction is the Five-Wing Radial Cellhouse, a nationally designated Important Cultural Property. This unique wooden building was actually used for more than 70 years, starting in 1912.

At the center is a guard station, with five long corridors extending outward like the fingers of a hand. This smart design allowed guards to monitor all areas with a small number of staff. As soon as you step inside, you can feel the strict and tense atmosphere of the past.

Five long corridors branch out from the central watch station.

The “Prison Road” Built at the Cost of Lives

The former Abashiri Prison was not just a detention facility. It also played a key role in a national project to develop Hokkaido.

Some of the major roads used in Hokkaido today were carved through deep forests by prisoners from Abashiri Prison. Chained together, they worked under extreme conditions that are hard to imagine from the simple phrase “building a road.” Many lives were lost during this brutal labor.

Along the old Prison Road, memorials like this stand in honor of those who died.

img: by pino

Inside the museum, the tragic history of the Prison Road is explained in detail. By learning about the heavy past behind today’s beautiful scenery, visitors can gain a deeper appreciation for freedom and a renewed sense of gratitude toward those who came before.

The History of Abashiri Prison

Let’s take a quick look at the history behind Abashiri Prison.

1. The Dawn of Hokkaido’s Development and the Birth of the Prison

img: by 663highland

After the Meiji Restoration, one of the government’s most urgent goals was the development of Hokkaido. At the time, Russia was expanding southward, and Japan also faced pressure from other foreign powers. To protect the region and secure its rich natural resources, the former land of Ezo was renamed Hokkaido, and large-scale development began.

However, most of Hokkaido was still covered in untouched wilderness. Building roads required enormous costs and manpower. The solution the government chose was to use prisoners from jails across the country.

Due to internal conflicts such as the Satsuma Rebellion, the number of inmates—including political prisoners—had rapidly increased, and prisons were overcrowded. Sending them to work in Hokkaido would solve two problems at once: creating space in prisons and securing a source of low-cost labor.

As a result, in 1890, Abashiri was chosen as the site for a new prison.

2. The Construction of the “Central Road,” Known as the Road of Death

About 1,200 prisoners at Abashiri were assigned an extremely harsh task: building the Central Road, a planned route stretching roughly 160 kilometers (about 100 miles) from Abashiri to the Kitami Pass.

There were no modern machines. Deep in the forests, the prisoners cut down massive trees and leveled the ground by hand. Food supplies were limited, and the combination of brutal labor and poor nutrition led to the spread of beriberi, a serious illness caused by vitamin deficiency.

Some prisoners, driven by desperation, tried to escape. If caught, they could be killed by guards. Even those who managed to flee had little chance of survival in the vast, untouched wilderness.

Amazingly, this forced construction was completed in just eight months. But the cost was high: more than 200 prisoners lost their lives. Because of this tragic history, the road later became known as the “Prisoners’ Road of Death.”

Today, visitors can enjoy driving along Hokkaido’s beautiful main highways.

Few realize that much of their foundation was built by prisoners from Abashiri, who carved these paths through the land at the cost of their lives.

Image source: Caption board inside the museum

3. Abashiri and the “Prison”: A History of Conflict and Benefit

The harsh development of Hokkaido relied heavily on prisoners serving long sentences for serious crimes. In the early 20th century, dangerous outdoor labor—such as the deadly road construction—was abolished. However, Abashiri continued to receive high-security inmates. This was likely because of its remote location and the strong security features of facilities like the Five-Wing Radial Cellhouse.

Because of this, many local residents strongly disliked the negative image of Abashiri as “a town of violent criminals and prisons.” Calls grew to change the name of Abashiri Prison. In 1938, the town of Abashiri formally submitted a petition to rename the prison. It passed in the House of Representatives but was ultimately rejected by the House of Peers.

At the same time, some longtime residents held a very different view. They said, “Without the prison, Abashiri would never have grown this much.” In fact, the opening of the Central Road became a key step in modernization and later supported the development of modern Hokkaido.

When the prison was first established, guards and their families moved to the area, causing a sharp increase in population. Many local industries also developed around the prison and its needs. In this sense, the “prison” brought significant economic and social benefits to the region.

img: by 663highland

4. “Prison” and Culture

Japan’s Most Famous Farm Prison

Abashiri Prison is widely known across Japan as a farm prison.

At the time, it adopted advanced modern farming systems from the United States and hired technical experts who had graduated from the Sapporo Agricultural College (now the Faculty of Agriculture at Hokkaido University). This greatly advanced cold-climate agriculture in the region.

It became the only prison in Japan to operate rice paddies, and in 1922 it was officially designated by the Ministry of Justice as a “Specially Equipped Farm Prison.” This made Abashiri a pioneer in the modernization of Japanese agriculture.

Even today, inmates continue to work in crop farming and livestock raising. In particular, “Abashiri Prison Wagyu” is known for its high quality, with some beef reaching the top A5 grade.

Film and Subculture

Abashiri Prison has long influenced Japanese culture as a symbol of Hokkaido’s harsh development history. Themes such as prison escapes, life in extreme cold, and human survival under pressure have been repeatedly portrayed in movies and manga, shaping a strong national image.

A famous example is the Abashiri Bangaichi film series, which began in 1965 and starred Ken Takakura. Produced by Toei, the series includes 18 films and became a classic of the yakuza movie boom. It tells action-packed stories of escaped prisoners and dramatic pursuits set around Abashiri Prison.

In modern times, the hit manga Golden Kamuy by Satoru Noda has brought Abashiri back into the spotlight. Abashiri Prison appears as a key setting in the battle over hidden gold.

One of the main characters, the “escape king” Yoshitake Shiraishi, is famously modeled after the real-life “Showa-era escape artist” Yoshie Shiratori, who was once imprisoned at Abashiri Prison.

The Five-Wing Radial Cellhouse, which also appears in the manga, is the main highlight of the Abashiri Prison Museum. Today, it has become a popular stop on fan “pilgrimage” routes, drawing visitors from Japan and around the world.

Explore the Exhibits: A Collection of Important Cultural Properties

Finally, let’s take a look at the main exhibition facilities at the Abashiri Prison Museum.

Important Cultural Property

“Five-Wing Radial Cellhouse”

The length of each wing varies. Some corridors stretch over 70 meters (230 feet).

The biggest highlight of the Abashiri Prison Museum is the Five-Wing Radial Cellhouse.

Built in 1912, this unique structure was modeled after Leuven Prison in Belgium. From a central watch station, five long wings spread outward in a radial pattern.

As you can see in the floor plan below, the shape looks like an open hand. This smart and efficient design allowed a small number of guards to monitor the entire facility from the center—an example of practical prison architecture.

This wooden prison building is considered one of the oldest of its kind in the world and is an extremely important historical site for both the development of Hokkaido and modern Japanese history.

In the early 1980s, as part of a major reconstruction project at Abashiri Prison, plans were made to relocate and preserve the building. In 1985, it was carefully moved and restored at its current location within the museum grounds.

It was first designated as a Registered Tangible Cultural Property in 2005. On February 9, 2016, it was officially upgraded to a National Important Cultural Property. Even today, it faithfully conveys what prison life was like in the past.

The Escape King of Abashiri Prison

img: by HSGryffindor

Famous as the real-life model for Yoshitake Shiraishi in the manga Golden Kamuy, Yoshie Shiratori is a legendary “escape king” who successfully broke out of prison four times in his lifetime.

One of the most shocking episodes took place in 1944, when he escaped from the heavily guarded Five-Wing Radial Cellhouse at Abashiri Prison.

In Abashiri, he was held in a special high-security cell for dangerous criminals. He was restrained with custom-made handcuffs and leg irons weighing nearly 20 kilograms (44 pounds), showing how closely he was watched by the guards. His treatment was extremely harsh: he was forced to wear only light clothing in the freezing winter and heavy clothing in the summer.

Unable to endure these conditions, Shiratori decided to escape. Twice a day, morning and night, he sprayed miso soup from his meals onto the bolts (or nails) that held the metal frame of the inspection window. Over several months to a year, the salt caused the metal to corrode and loosen. Eventually, he was able to remove them.

The inspection window was extremely small—only about 20 by 40 centimeters (8 by 16 inches). However, Shiratori had the unusual ability to dislocate his shoulders and joints, allowing him to squeeze his entire body through once his head fit.

After reaching the corridor, he climbed the wall and smashed through a skylight with his head, successfully making his escape.

Shiratori also escaped from prisons in Aomori, Akita, and Sapporo. Yet he was known for his surprisingly human side. In some cases, he turned himself in after visiting a former chief guard who had once helped him, or after being deeply moved by the kindness of a police officer who offered him a cigarette.

Important Cultural Property

“Administration Building”

This is the first building you see as you pass through the museum’s main gate. In contrast to the red-brick gate, the Western-style exterior is painted in bright gray and light blue, giving it a modern look that was rare for its time.

The building was constructed in 1912, after a major fire in 1909. It was designed by the Ministry of Justice and built by prisoners. Inside, it was equipped with a boiler and a steam-powered generator.

Thanks to this system, electric lights were turned on here for the first time in the town of Abashiri. The cellhouses and the administration building were lit 24 hours a day. Because the lights never went out, the site was said to be known as the “Northern City That Never Sleeps.”

Today, the building serves as a museum gallery. Visitors can read detailed caption boards about the history of Abashiri Prison and browse related books. In winter, it is also one of the few heated spaces in the museum, making it a perfect place to warm up and take a short break.

There is also a small café corner. The coffee is excellent.

Important Cultural Property

“Futamigaoka Prison Branch”

The Futamigaoka Prison Branch began in 1896 as the Kussharo Outdoor Work Office, which led agricultural work for Abashiri Prison.

The existing buildings—such as the administration office, cellhouse, and kitchen (built in 1896), and the chapel and dining hall (added in 1926)—are among the oldest surviving wooden prison buildings in Japan.

In 1999, these structures were relocated and restored at the Abashiri Prison Museum. On February 9, 2016, the site was officially designated as a National Important Cultural Property.

Originally located in the western hills of Abashiri Prison, this branch housed prisoners who worked in farming. Its defining feature was its open-style system with no surrounding walls. Selected inmates who had earned trust were allowed to work independently as they prepared for life after release.

Escape attempts at such open facilities are extremely rare. However, in 2018, an escape did occur at the wall-less Oi Shipyard work site of Matsuyama Prison. At Futamigaoka, a similar incident reportedly took place around 1981, but no major cases have been recorded since.

While prisons exist to separate offenders from society, they also serve as places of rehabilitation and reintegration. Facilities like this are built on a foundation of trust between inmates and guards.

Important Cultural Property

“Kyokaido (Spiritual Guidance Hall)”

This building is known as the Kyokaido, a hall where religious leaders and prison chaplains provided mental, moral, and spiritual guidance to inmates.

While the design came from the Ministry of Justice, the building itself was constructed by the prisoners. This Kyokaido was said to be built with special care, as it was considered a “home for gods and Buddhas,” and inmates put more heart and effort into it than any other structure.

The exterior features a calm traditional wooden hip-and-gable roof style. Inside, however, the space is bright and open, with plaster-like walls and very few columns, creating a wide, airy hall.

After World War II, the building was also used for light sports and recreation, becoming a place where inmates could relax and take a break from daily life.

Prison Cafeteria

At the Prison Cafeteria inside the Abashiri Prison Museum, visitors can try the same meals served to inmates at the modern Abashiri Prison.

A typical “prison meal” includes barley rice (about 70% white rice and 30% barley), grilled fish (usually Pacific saury or Atka mackerel), a small side dish, and miso soup. Simple but surprisingly satisfying, it is very popular with tourists.

When I visited, the cafeteria was unfortunately closed. In general, it operates on museum open days and can be used without purchasing a museum ticket.

Please note that it is open for lunch only, from 11:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. (last order at 2:30 p.m.). It is often closed during the winter season, so checking in advance is highly recommended.

Final Thoughts: Abashiri Prison and the History of Hokkaido

This time, we introduced a truly unique open-air museum—the Abashiri Prison Museum, a rare attraction in Japan that focuses on the history of a real prison. What did you think?

The word “prison” may bring to mind a dark and intimidating image. However, it is no exaggeration to say that without the harsh labor of prisoners, the development and growth of Hokkaido would not have been possible.

From the construction of the Central Road to the clearing of vast farmland and the building of early infrastructure, Abashiri Prison and its outdoor labor system played a crucial role in laying the foundations of modern Hokkaido.

Over time, serious criminals continued to be sent here from across Japan, and the image of Abashiri as a remote, freezing northern frontier became deeply linked with the idea of a “prison town.” Some local residents even opposed this negative image and once submitted a petition to change the prison’s name.

Still, the fact that an entire town grew and developed around a prison is extremely rare in modern Japanese history. This unique relationship between Abashiri and its prison remains a valuable cultural legacy.

If you visit Hokkaido, be sure to stop by the Abashiri Prison Museum. As you walk through the wooden buildings of the Meiji and Taisho eras, you will gain a deeper understanding of both the bright and dark sides of Hokkaido’s history—making this an unforgettable travel experience.

Visitor Information – Abashiri Prison Museum

Location: 1-1 Yobito, Abashiri City, Hokkaido, Japan

Comments