A Bold, Modern — Fukuda Art Museum in Kyoto

When you think of Kyoto’s Arashiyama district, classic sights like Togetsukyo Bridge, bamboo groves, and rickshaws probably come to mind.

It’s one of the city’s most popular tourist areas—a place that’s always lively with people eager to experience the essence of Kyoto.

But did you know there’s a relatively new art museum tucked away in this bustling area?

Opened in 2019, the Fukuda Art Museum brings something fresh to this historic neighborhood.

And make no mistake—this isn’t just another newly built museum.

It’s a bold and forward-thinking space that’s redefining what an art museum can be.

The museum’s concept is to last for 100 years.

Its collection includes timeless masterpieces, yet the way they’re presented is anything but traditional.

For example, Japanese and Western paintings are often displayed side by side—a curatorial style that breaks conventions and sparks new ways of seeing.

You Can Take Photos of Japanese Paintings?!

One of the most surprising (and exciting!) features of the Fukuda Art Museum is that photography is allowed for most of the artworks.

Yes, you read that right—you can snap photos of Japanese paintings, which are usually strictly no-camera.

Feel free to take pictures with your smartphone (just no flash), and even share them on social media.

It’s a refreshingly modern approach that makes the museum experience more personal and memorable.

Blending traditional Japanese art with innovative exhibits and presentation, the Fukuda Art Museum offers a unique experience that fits perfectly into the natural beauty of Arashiyama.

Whether you’re strolling through the area on a sightseeing trip or making art the main focus of your day, this museum is worth a visit.

Looking for a bit of inspiration or something different?

This is one spot that will definitely spark your curiosity.

🎨 Highlights from the Collection

The Fukuda Art Museum is a dream destination for anyone who loves traditional Japanese painting.

The lineup includes some of the biggest names: Jakuchu Ito, Buson Yosa, Seiho Takeuchi, and Yumeji Takehisa, just to name a few.

Here, we’ll introduce a few must-see pieces from the collection.

If something catches your eye, make sure to take your time and see it up close when you visit.

Jakuchu Ito, “Rooster and Hen with Turnips” (18th Century)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

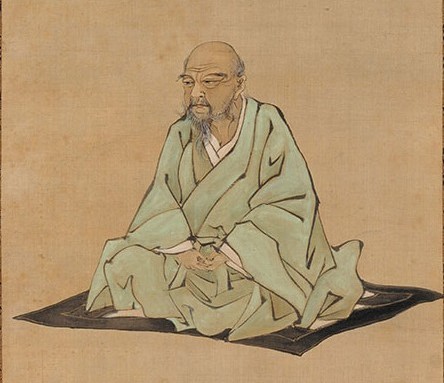

Jakuchu Ito was one of the most beloved artists of the mid-Edo period.

He is especially known for his intricate and imaginative depictions of plants and animals.

And when it comes to Jakuchu, one animal shows up again and again: the rooster.

Roosters appear so frequently in his work that it’s safe to say he was truly fascinated by them.

In this painting, Rooster and Hen with Turnips, you’ll see two striking birds front and center.

The pose of the rooster in particular stands out—with its flowing feathers, strong legs, and expressive face, it feels almost lifelike.

It’s amazing to think that Jakuchu could capture such realistic motion and anatomy in a time long before cameras existed.

Don’t miss the turnip leaves in the background either.

Look closely, and you’ll notice tiny details like insect bites and fading colors.

This mix of realism and decorative flair is a signature of Jakuchu’s unique artistic sense.

Interestingly, this work was only rediscovered in 2019.

Based on its composition and brushwork, experts believe it was painted in his early 30s—before he fully devoted himself to art in his 40s.

That makes this a rare and valuable glimpse into his early style. If you’re a Jakuchu fan, this piece is a must-see.

Every detail—from the movement to the color to the character—captures the essence of what makes Jakuchu so special.

Shohaku Soga, “Dragon in the Clouds“ (1771–1781)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

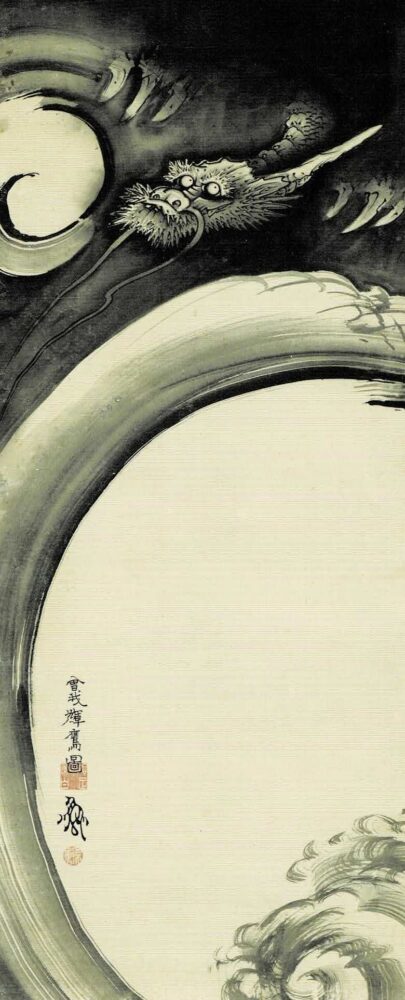

Shohaku Soga was one of the most eccentric artists of the Edo period—especially when it came to ink painting.

His bold and unconventional style sets him apart in the world of Japanese art.

Dragon in the Clouds is a perfect example of his unique flair.

At first glance, you’ll notice the dramatic sweeping curve that forms the central composition.

It’s a daring layout that may seem chaotic at first, but it actually draws your eyes in a circular motion across the entire painting.

Take a closer look at the dragon’s face at the top of the scroll.

Emerging from a dark cloud, it has an oddly charming, almost humorous expression—more human than fearsome.

The careful detail work shows Shohaku’s incredible balance of humor and technical skill.

While the piece may feel spontaneous, it’s full of thoughtful choices—like his use of ink tones and compositional rhythm.

That’s where you can really see his creativity and mastery at work.

Unorthodox, yes—but not just weird for the sake of it.

This piece is a brilliant mix of playfulness and precision. Don’t miss the chance to see it in person.

Tanyu Kano, “Dragon in the Clouds” (1666)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

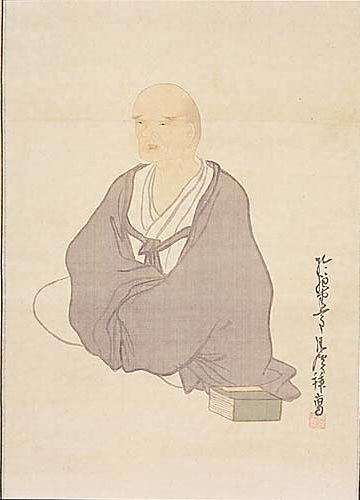

Tanyu Kano was a leading figure in the Kano school, which dominated Japanese art during the early Edo period.

While his grandfather Eitoku Kano was known for his bold and lavish style, Tanyu took a different path—valuing elegance, simplicity, and the use of empty space.

This piece, Dragon in the Clouds, was painted in Tanyu’s later years.

Although Tanyu is often associated with more tranquil, serene works, this dragon has an undeniable intensity.

Its face stares directly forward, with masterful ink shading used in the outlines to give the figure a soft, floating sense of three-dimensionality.

In contrast, the clouds are delicate and ethereal.

Using techniques like blurring and ink bleeding, Tanyu creates a vapor-like texture that heightens the tension between the calm clouds and the powerful dragon.

Of course, he also leaves plenty of empty space—a signature of his style.

The balance between what’s painted and what’s left blank gives the work a quiet intensity, as if the image is slowly emerging from silence.

This is a dragon full of quiet strength—a perfect example of how refined brushwork and restraint can still create dramatic impact.

Buson Yosa, “Fierce Tiger and Waterfall” (1767)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Buson Yosa is most famous as a haiku poet, but he was also a skilled painter.

A self-taught artist, Buson blended poetic sensitivity into his paintings, creating art that feels like “visual haiku.”

This piece, titled Fierce Tiger and Waterfall, sounds intense—but the tiger itself has a surprisingly playful charm.

That’s because in Buson’s time, tigers didn’t exist in Japan. Artists had to imagine them based on imported tiger pelts or rugs, leading to some creative interpretations.

As a result, you’ll notice some quirky details—like the tiger’s slightly off-center spine or oddly shaped eyes.

But that’s part of what makes it so endearing.

Its pose is almost cat-like, and the slightly silly expression gives the piece a warm, almost cartoonish appeal.

The composition is also worth noting: bamboo shoots dominate the foreground, while a waterfall cascades in the back, creating a sense of depth.

Rather than focusing on realism, Buson aimed to capture an atmosphere—something poetic, gentle, and emotionally resonant.

It may not be a textbook tiger, but this painting radiates personality and poetic beauty.

It’s a perfect example of Buson’s talent for expressing emotion through both words and brushstrokes.

Seiho Takeuchi, “Golden Lion” (1906)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

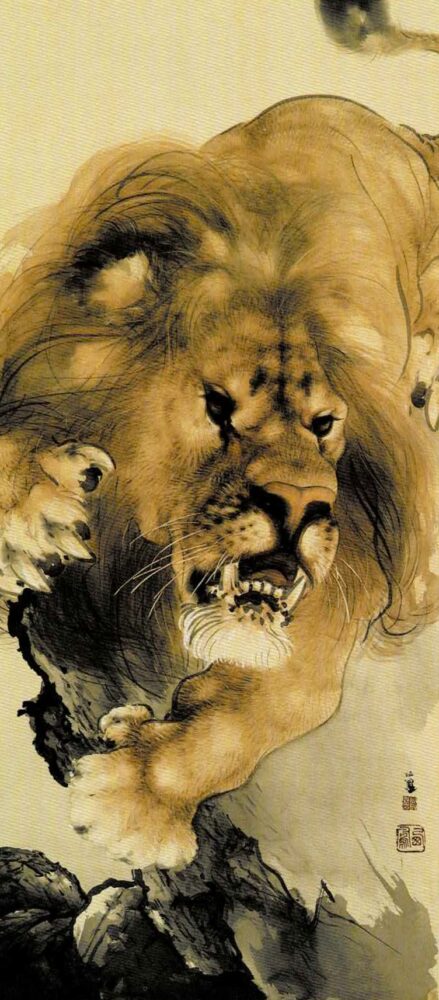

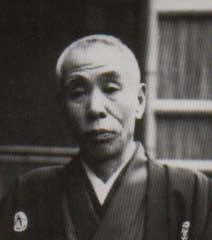

Seihō Takeuchi was a groundbreaking painter who brought new life to Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) during the Meiji to early Showa periods.

He respected traditional Japanese techniques while embracing Western realism and methods—blending both worlds in his art.

In 1900, he traveled to Europe to visit the Exposition Universelle in Paris, where he encountered a lion sketch by Jean-Léon Gérôme. Deeply inspired, Seihō extended his stay to spend time at local zoos, sketching and studying lions in detail.

After returning to Japan, Seihō began creating powerful lion paintings.

Golden Lion is one of the best examples from this period.

The golden lion dominates the canvas, as if leaping toward the viewer.

Though the brushwork may look simple, every detail—from the sharp claws to the rich mane—reflects his careful study of the animal.

The bold composition and tight framing add intensity and drama to the piece.

At the time, Japanese art often depicted imaginary lions like the mythical Kara-shishi.

So Seihō’s realistic portrayal of an actual lion made a huge impression on viewers.

This painting represents the fusion of traditional Japanese art with Western realism and real-world observation—a true testament to Seihō’s spirit of innovation.

Collection of Sannomaru Shozokan

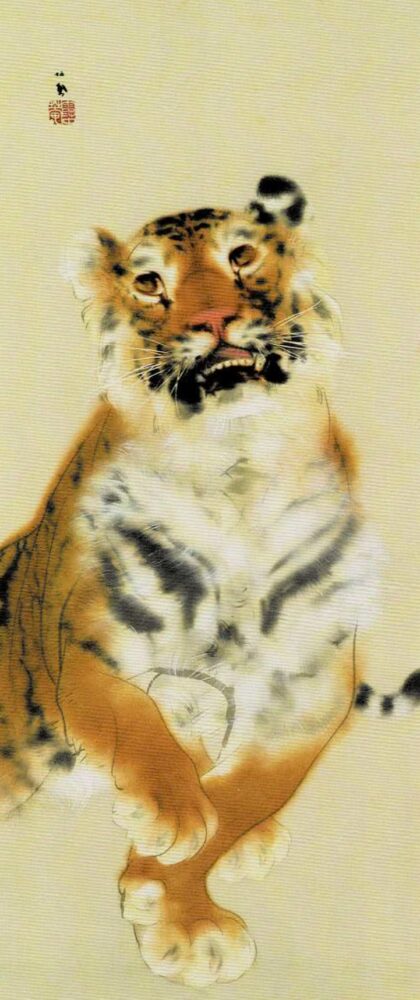

Seiho Takeuchi, “Fierce Tiger” (1930)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

While Seihō Takeuchi is well known for his lifelike animal paintings, another hallmark of his work is the “shōhitsu” technique—a minimalist style that uses only essential lines and brushstrokes to capture the essence of the subject.

In Fierce Tiger, this minimalist approach shines.

The composition is similar to Golden Lion, but the tiger is drawn with even cleaner lines and a more refined color palette.

Despite the simplicity, the tiger still feels powerful—especially in the way its fur is gently suggested with just a few strokes.

Interestingly, although the title says “Fierce,” the tiger’s expression is quite the opposite.

Its tilted head and upward gaze feel gentle, even a little curious—more cute than threatening.

Seihō didn’t aim for realism alone.

He carefully observed animal behavior and captured fleeting expressions and subtle gestures that reveal character and emotion.

By removing the unnecessary, he distilled each subject down to its most essential traits.

That’s what makes this painting so expressive—a perfect example of beauty in restraint, and one of Seihō’s quiet masterpieces.

🎨 Just a Touch of French Modern Art

Though best known for its outstanding collection of Japanese-style paintings, the Fukuda Art Museum also quietly (but confidently) houses several works by French modern masters.

It’s another example of the museum’s boundary-breaking spirit—unafraid to blend different traditions and challenge expectations.

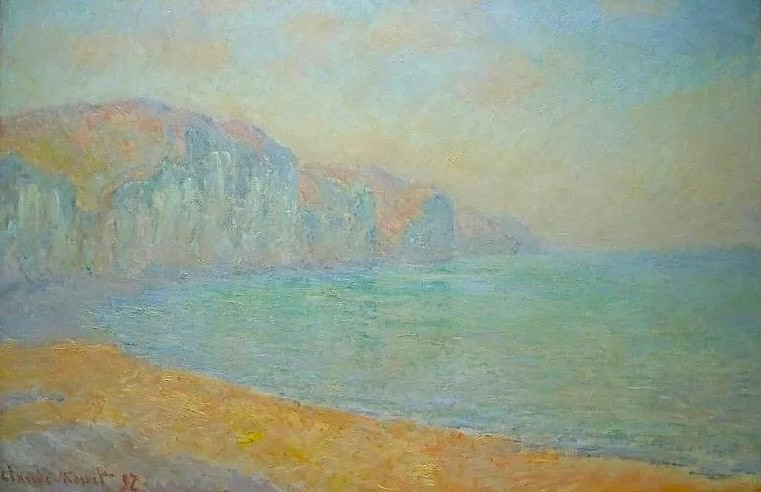

Claude Monet, “Cliffs at Pourville in the Morning“ (1897)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

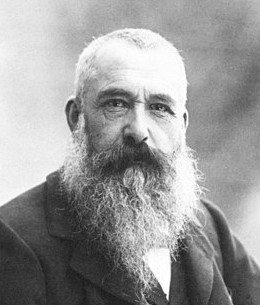

Claude Monet is widely regarded as the father of Impressionism.

This painting captures the morning light gently illuminating the sea and cliffs of Pourville, a seaside village on the coast of Normandy—one of Monet’s favorite subjects.

Monet spent part of his childhood in Le Havre, a port town in northwestern France, and remained emotionally connected to the Normandy coast throughout his life.

He returned to this area many times to paint scenes of the sea, sky, and shoreline.

In this piece, the morning light glows softly across the cliffs, while the calm sea shimmers in gentle tones.

The outlines are intentionally blurred, emphasizing light, air, and atmosphere over solid form—hallmarks of the Impressionist style.

It’s a classic Monet work that beautifully captures the fleeting beauty of a single moment in nature.

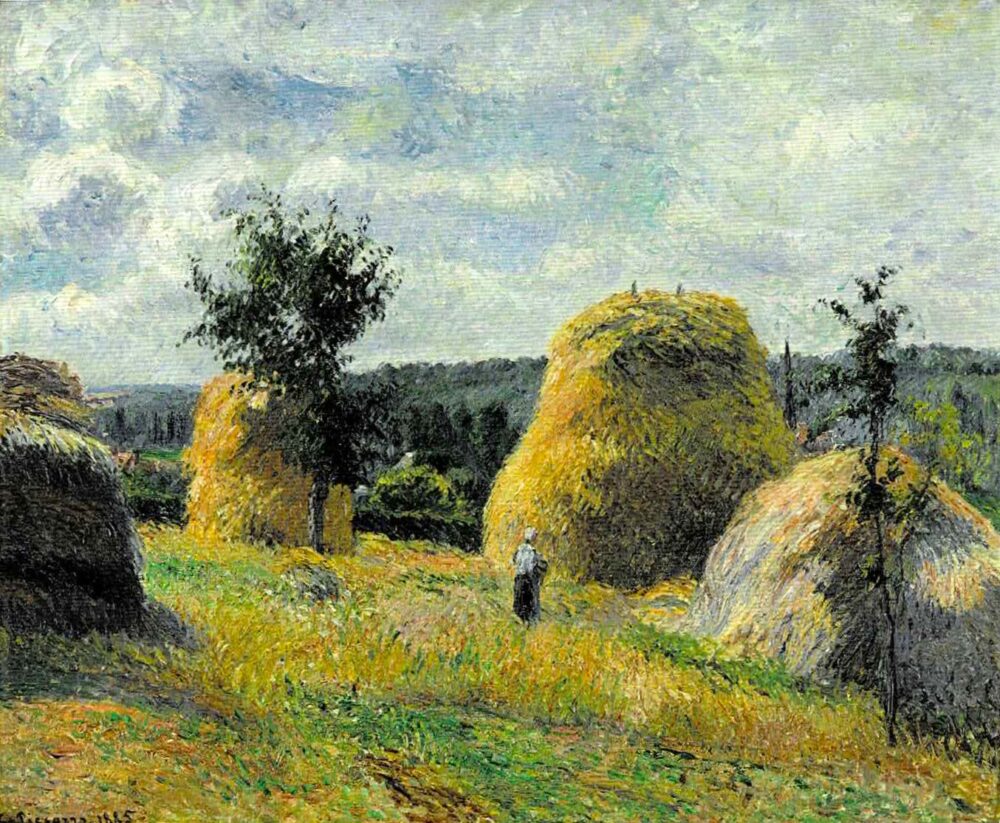

Camille Pissarro, “Haystack and Farm Woman at Éragny” (1885)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

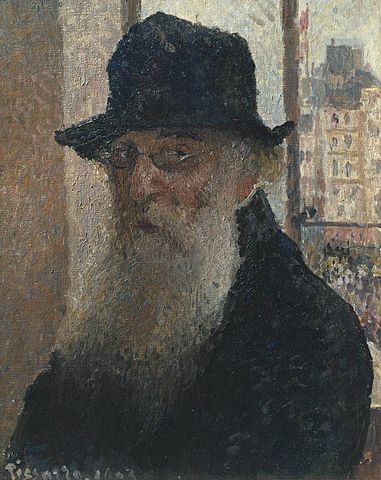

Camille Pissarro was another founding figure of Impressionism—and his work is also represented in the Fukuda Art Museum’s Western collection.

In 1884, Pissarro moved to the quiet village of Éragny, northwest of Paris, where he lived for the rest of his life.

This painting comes from his “Éragny period.”

We see a rural scene: a farmer woman at work and a haystack towering in the field.

The composition is filled with gentle natural light, giving it a peaceful, timeless atmosphere.

The brushwork is precise, the colors warm and earthy—showing the transition in Pissarro’s technique as it became more refined over time.

Soon after this period, Pissarro would be influenced by artists like Georges Seurat and explore Pointillism during his Neo-Impressionist phase.

But here, we already see the sensitivity and deep connection to nature that remained at the heart of all his work.

Fukuda Art Museum – Visitor Information

Location: 3-16 Sagatenryuji Susukinobabacho, Ukyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan

Comments