Just a 5-minute walk from Tokyo Station!

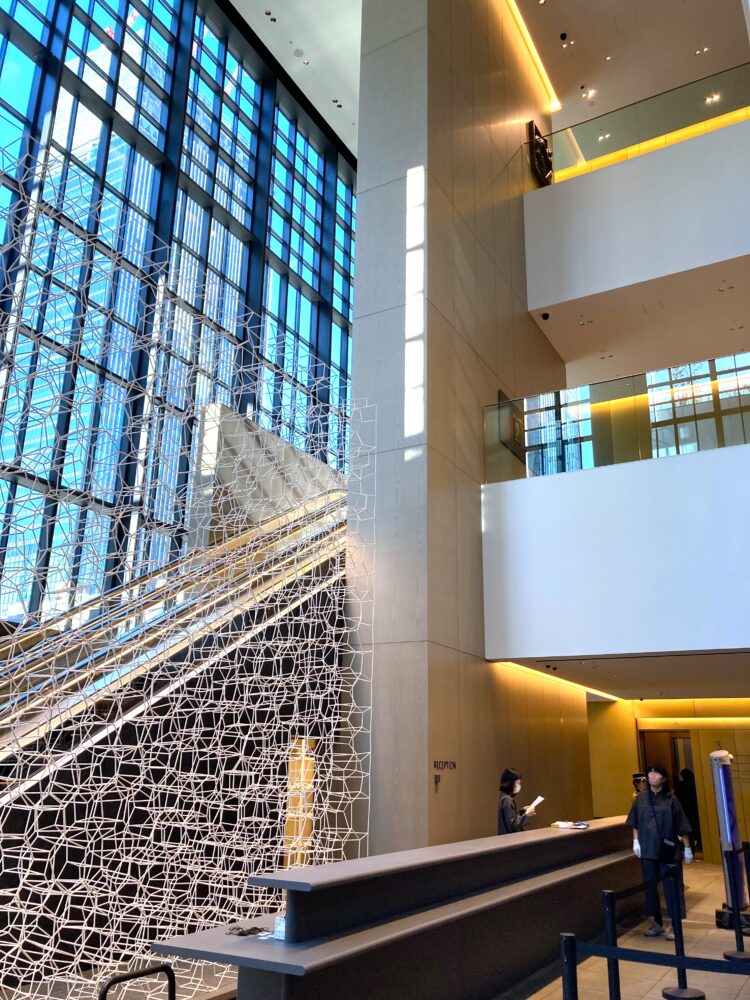

Escape the busy business district and step into the peaceful world of the Artizon Museum.

Located about 5 minutes on foot from the Yaesu Central Exit of Tokyo Station, the Artizon Museum sits quietly—but confidently—in the heart of the city’s bustling office area.

This museum is actually a new cultural spot that opened in 2020. It was formerly known as the Bridgestone Museum of Art, which closed temporarily in 2015 for the reconstruction of its building. After the renewal, it reopened with a brand-new name and a modern, state-of-the-art facility.

The name “Artizon” is a coined word that combines Art and Horizon. It reflects the museum’s mission to “expand the horizons of art” and introduce new artistic perspectives to the world.

Once inside, you’ll be surprised by how spacious it feels, especially for a museum inside an office building. The total gallery space is over 6,700 square meters. With thoughtfully designed lighting, layout, and flow, it offers a calm and comfortable environment to enjoy the art.

One more thing to note—on Fridays, the museum stays open until 8:00 p.m. It’s a great way to unwind after work and refresh your mind with beautiful art.

The Ishibashi Foundation Collection

The Artizon Museum isn’t just about its beautiful space—it’s also home to an outstanding art collection. At the heart of the museum’s exhibitions is the Ishibashi Foundation Collection, built over many years by Shojiro Ishibashi (1889–1976), the founder of Bridgestone Tire.

One of his first passions was collecting works by Shigeru Aoki, a Western-style painter from Kurume, Ishibashi’s hometown. Aoki’s famous paintings, such as Umi no Sachi (A Gift of the Sea) and Wadatsumi no Irokonomiya, are now recognized as Important Cultural Properties of Japan. Seeing them in person is a truly powerful experience.

What makes the Ishibashi Collection special is how diverse it is. It goes far beyond just Aoki or Japanese modern art. The collection includes French Impressionist paintings, abstract works, East Asian art, and even pieces from ancient Mesopotamia and Greece. It’s rare to find such a wide-ranging collection all in one museum—even in Tokyo.

Collection Highlights: Masterpieces You Can Discover at Artizon

The museum’s collection consists of about 3,000 works from the Ishibashi Foundation. Among them, the selection of modern Western paintings is one of the finest in Japan. You’ll find masterpieces by world-famous artists, making every visit a rewarding experience.

Rembrandt van Rijn, “A Biblical or Historical Nocturnal Scene” (1626–1628)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

This early painting by the Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn was created when he was still in his early twenties. Even at this young age, his remarkable ability to paint with light and shadow—the very skill that later earned him the nickname “the magician of light”—is already on full display.

The glow of the fire on the left side gently illuminates the surrounding figures. Light reflects off the central figure’s armor and outlines another figure in silhouette, creating a dramatic and tense atmosphere. Every beam of light and patch of shadow tells a part of the story.

Interestingly, the left edge of the painting has been trimmed, so the original composition is incomplete. As a result, the exact biblical or historical scene remains unclear. Still, the facial expressions, gestures, and mood of the figures bring the scene to life, even without knowing the specific context.

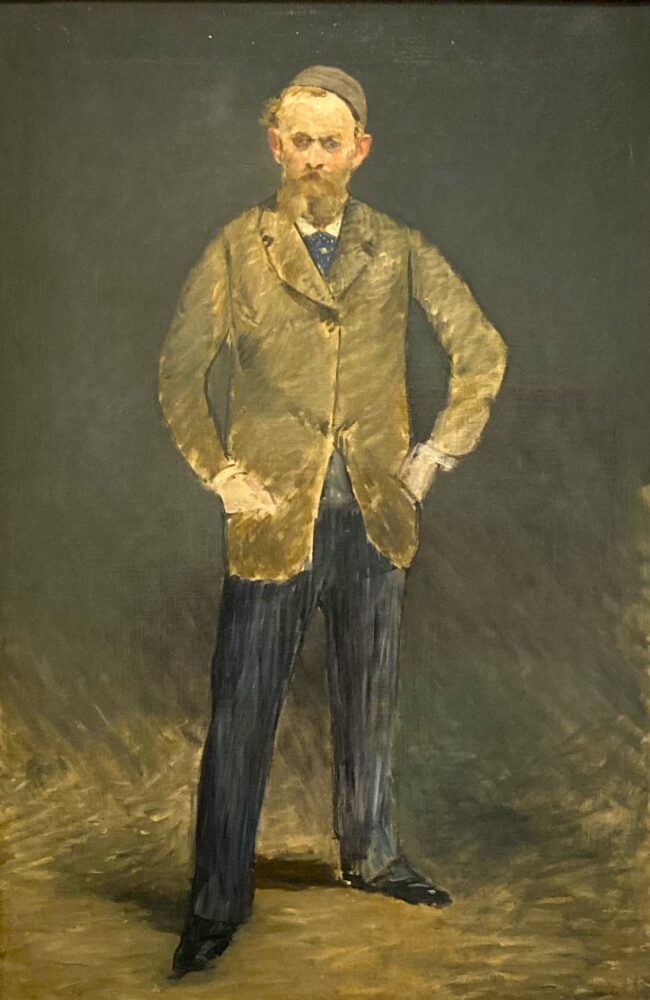

Édouard Manet, “Self-Portrait” (1878–1879)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

French painter Édouard Manet, often seen as a pioneer of Impressionism, rarely painted self-portraits. In fact, only two are known to exist—and this full-body “Self-Portrait with a Hat” is one of them.

Unlike the typical head-and-shoulders format, this rare portrait shows Manet standing and facing the viewer with a calm, introspective gaze. It doesn’t feel like an emotional deep dive, but rather a quiet, objective reflection of himself.

Manet painted this piece near the end of his life, when his health was deteriorating due to syphilis. He suffered from severe pain in his left leg, and in the painting, he appears to be placing more weight on his right side (which, in a mirrored self-portrait, appears as the left leg).

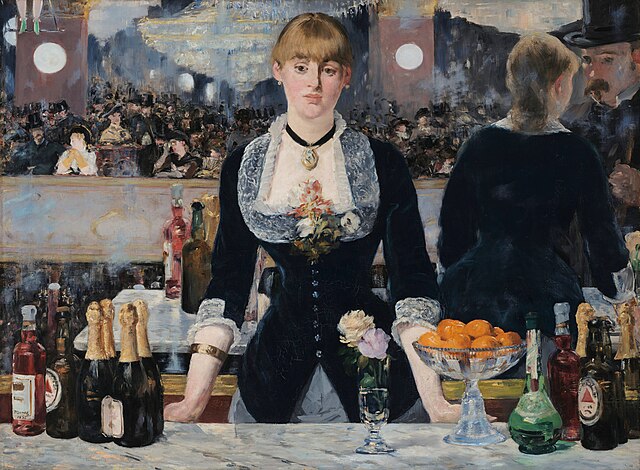

Despite his illness, Manet continued to paint with passion—he even completed his famous work A Bar at the Folies-Bergère during this time. This self-portrait, free from dramatic gestures or embellishments, expresses his unwavering commitment to art and his determination to live as a painter until the very end. Quiet yet powerful, it leaves a lasting impression.

from Collection of the Courtauld Gallery

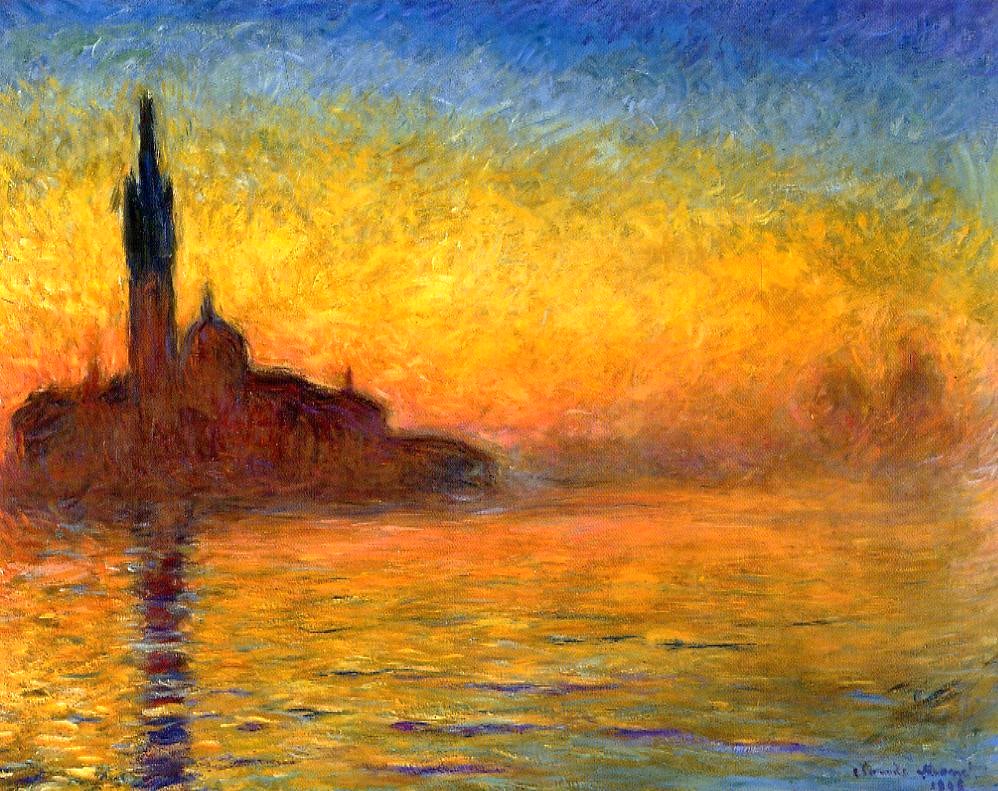

Claude Monet, “Twilight, Venice” (c. 1908)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

This dreamlike painting by Claude Monet, the master of light, was created during his trip to Venice with his wife Alice.

The scene captures the quiet beauty of twilight. As night falls, the sky darkens, and the silhouette of the Church of San Giorgio Maggiore appears above the shimmering water. It’s a magical moment, gently painted across the canvas.

The colors—orange, yellow, blue—may seem vivid at first glance, but this is not simply a show of brightness. Instead, Monet carefully portrays the changing light of nature, a hallmark of Impressionism at its finest.

At the time, Monet was suffering from cataracts, which were beginning to affect his vision. This might explain the painting’s soft focus and almost dreamlike haze. In many of his later works, we see deeper colors and blurred outlines—but rather than flaws, these features add a poetic quality to the art.

The quiet of dusk, the passing of time, and Monet’s tireless pursuit of light—even as his vision faded—are all felt in this one powerful image.

img: by Didier Descouens

Camille Corot, “Young Woman in the Woods” (1865)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Camille Corot is best known as a landscape painter of the Barbizon School.

But this portrait, “Young Woman in the Woods,” makes you stop and think—his figure paintings are just as powerful.

The background suggests a forest scene, but look closely and you’ll notice it’s abstract, almost separate from the figure. That’s because the painting wasn’t made outdoors. It was carefully composed in Corot’s studio. By working under steady lighting rather than changing natural light, he could capture the model’s expression and the textures in fine detail.

From the softness of the woman’s skin to the delicate folds of her clothing, everything is rendered with extraordinary sensitivity.

If Corot’s landscapes are known for their atmosphere, this portrait is about presence.

The model’s calm gaze, the warmth of her skin, and the quiet weight of her clothes—all of it draws you in. Before you know it, you’ve stopped walking, lost in the moment.

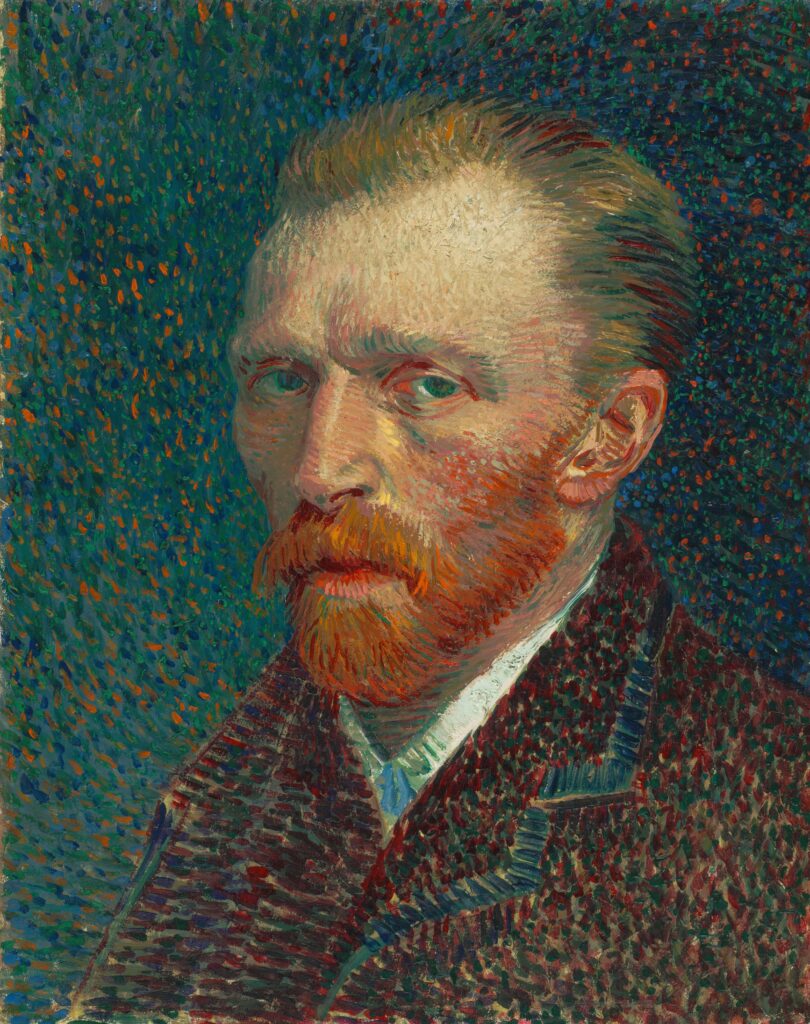

Vincent van Gogh, “Windmills on Montmartre” (1886)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

When you think of Vincent van Gogh, vivid colors and swirling brushstrokes probably come to mind.

But it took time for Van Gogh to develop that iconic style—and this painting captures a moment right in the middle of that artistic transformation.

He didn’t start painting until the age of 27, a relatively late beginning. Early in his career, Van Gogh was inspired by the Barbizon painter Jean-François Millet, creating dark-toned works focused on peasants and rural life. These early pieces had a heavy, muted style—very different from the Van Gogh most people imagine.

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

In 1886, everything began to change. Van Gogh moved to Paris to live with his brother Theo, where he encountered Impressionist painters and their vibrant, light-filled techniques.

“Windmills on Montmartre” was painted during this very turning point.

Back then, Montmartre still had open natural spaces, and the neighborhood was a hub for artists and studios.

The soft sky, quiet windmills, and glowing air—all of it reflects Van Gogh’s first steps toward painting outdoors and embracing natural light. You can feel his excitement and curiosity as he experimented with a new approach.

Interestingly, during this same time, Van Gogh became fascinated with Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints. He was especially drawn to their bold compositions and vivid colors—both of which began to influence his work more and more.

Van Gogh’s two years in Paris were brief but transformative.

This painting marks a pivot, a bridge between the darkness of his early years and the vibrant vision he would later become famous for.

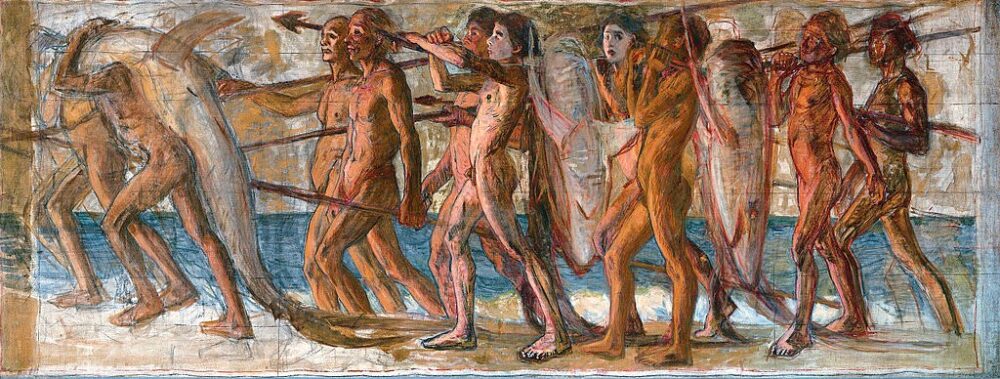

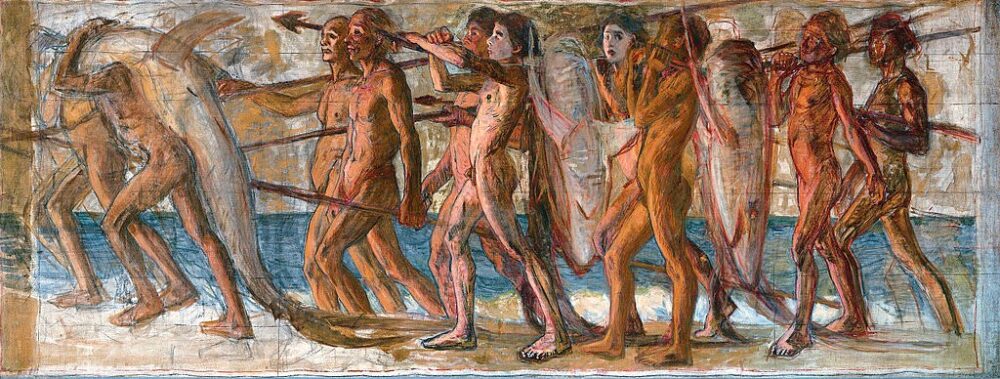

Shigeru Aoki, “A Gift of the Sea” (1904)

[Important Cultural Property]

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

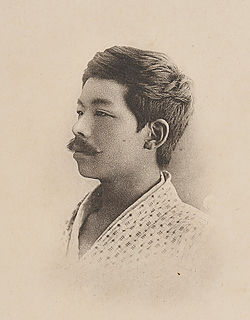

When people think of Shigeru Aoki (1882–1911), this painting—“A Gift of the Sea”—is the one that always comes to mind. It’s his most iconic masterpiece.

And yet, this powerful work almost disappeared forever.

It was only saved thanks to fellow artist and rival Hanjiro Sakamoto, who urged, “This must be preserved.” That plea reached Shojiro Ishibashi, founder of the Bridgestone Museum (now Artizon Museum), who purchased the piece—making it possible for us to admire it today.

Even better, the museum also houses other major Aoki works like “Paradise under the Sea” and “Oanamuchi no Mikoto”, making it a must-visit for fans.

Painted in 1904, “A Gift of the Sea” was born during a sketching trip to Mera Beach in Tateyama, Chiba, shortly after Aoki graduated from Tokyo Fine Arts School.

The large canvas shows a group of nude fishermen walking in line, carrying a shark on their shoulders. The brushwork is rough, energetic, and expressive—yet the overall scene has a mysterious, spiritual feel.

The way the figures all face sideways, with a kind of rhythm and unity, recalls the style of ancient Egyptian wall paintings.

This isn’t just a sketch of fishermen. It’s Aoki’s attempt to capture the essence of Mera’s coastal culture and spirituality.

On a deeper level, it may even express a universal theme: human life in harmony with nature.

A Gaze That Stops You

Among the fishermen, look closely at the figure to the right.

Unlike the others, this person faces the viewer directly—with a piercing, almost androgynous stare that fills the painting with quiet tension.

Some believe the model was Aoki’s lover, Tane Fukuda, who also posed for his other work “Oanamuchi no Mikoto.” The face does resemble the character Sagai-hime in that piece.

There’s no definitive proof, and no clear reason why Aoki would insert her into this painting of fishermen—but her mysterious presence elevates the entire composition.

Thanks to that one enigmatic figure, “A Gift of the Sea” becomes more than a scene of coastal life—it becomes something unforgettable.

Collection of the Artizon Museum

Sotaro Yasui, “Bathers” (1914)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Sotaro Yasui is a key figure in the history of modern Western-style painting in Japan. Active from the Taisho era into the Showa era, he played a major role in expanding the possibilities of yōga (Western-style painting) in Japan.

He traveled to France in his late teens and studied there for seven years. During this time, he was deeply influenced by French masters—especially Paul Cézanne and Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Bathers was painted toward the end of his stay in France. It’s a large-scale piece that shows nude women bathing in a forest spring, surrounded by soft, glowing light.

The women’s skin is beautifully smooth, almost glowing with warmth as if bathed in sunlight through the trees. If the atmosphere feels familiar, you’re not wrong—it strongly recalls Renoir’s The Great Bathers.

At the same time, the solid texture of the rocks and cloth in the background is more structured, like the style of Cézanne. The painting blends softness and strength, giving the sense that Yasui drew inspiration from both masters.

While it echoes those influences, this painting is far from a simple imitation. Yasui masterfully balances the use of outlines and color, creating a natural harmony between the forest and the figures. It feels Impressionist, yet the composition is thoughtful and clear.

What shines through is not just what he learned in France, but his deep effort to make something of his own. Through this piece, we see Yasui in the process of discovering his unique artistic voice.

Collection of Philadelphia Museum of Art

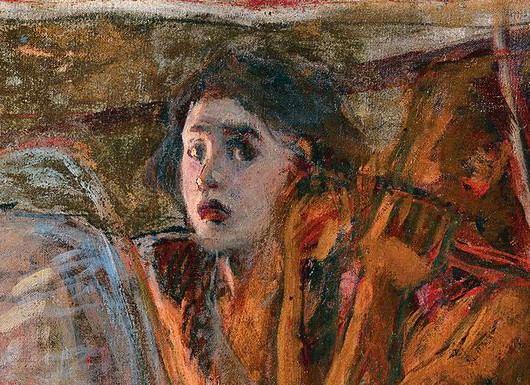

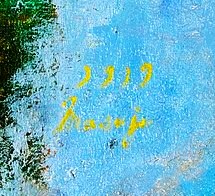

Shoji Sekine, “Boy” (1919)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Shoji Sekine is often called a “legendary” artist in modern Japanese painting—because he passed away at only 20 years old. Though his career lasted just a few short years, his intense and emotional works continue to fascinate audiences today.

Boy, painted in the year of his death, is one of his most striking pieces. The vivid colors—sky blue background with a bold red-orange kimono—grab your attention immediately.

While most of the brushwork is rough and expressive, the boy’s face is painted with a delicate, careful touch. His eyes draw you in, as if he’s quietly looking beyond the canvas. There’s something deep and thoughtful behind his innocent expression.

Another unique feature of this work is Sekine’s signature. Normally, he signed his paintings as “S. Sekine” in English. But when he painted children—especially boys or girls—he sometimes signed them “Masaji,” a reference to his given name, Masaji Sekine.

You can spot the name Masaji in yellow script on the left side of the painting. It seems that painting children may have stirred something deeply personal in him—perhaps a connection to his own childhood.

Some even see this painting as a kind of self-portrait, reflecting how he saw himself or his past.

To this day, the exact reason he used different signatures remains a mystery. But that ambiguity adds to the emotional depth of the painting, inviting each viewer to bring their own interpretation—and that’s part of what makes Shoji Sekine’s work so unforgettable.

(written in cursive script)

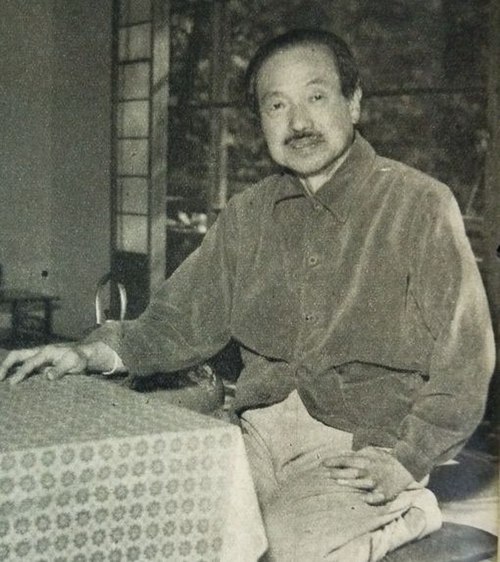

Kunishiro Mitsutani, “Seated Woman“ (1913)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Kunishirō Mitsutani was a key figure in the development of Western-style painting in Japan during the late Meiji and early Showa periods.

In his early career, he was known for detailed, academic-style realism. But everything changed when he traveled to Europe in 1911, supported by Magosaburō Ōhara, founder of the Ohara Museum of Art. In France, Mitsutani studied under Jean-Paul Laurens and embraced a more impressionistic, loose, and flat style, moving away from his previous precision.

Seated Woman was painted right during this artistic transition. The subject—a woman sitting on a chair—might seem like a simple, classic scene. But the mood in the painting is what makes it special.

Instead of focusing on realistic facial details or intricate textures, Mitsutani captures the soft light entering the room and the quiet passage of time. His brushwork is rough and minimal, but that simplicity highlights the calm atmosphere and empty space around the subject.

It’s a peaceful, everyday moment—but there’s a poetic quality to it. It’s not flashy, but it quietly pulls you in. A beautiful example of how less can be more.

Final Thoughts: A Quiet Place to Enjoy Art

Although the Artizon Museum is home to many masterpieces and world-famous artists, it still feels calm and peaceful.

It’s not a noisy tourist spot—it’s more like a hidden gem where adults can enjoy art in a relaxed setting.

The galleries are spacious, with thoughtful lighting and layout that allow visitors to take their time and fully appreciate each artwork.

Beyond the works mentioned in this article, the museum holds many other treasures. Every new exhibition rotation brings fresh discoveries.

If you ever think, “I’d like to visit a museum, but where should I go?”, this is the kind of place you’ll want to remember.

A short escape from your busy day—time to enjoy something beautiful with your eyes and heart.

The Artizon Museum is the perfect place for that kind of experience.

Visitor Information – Artizon Museum

Location: 1-7-2 Kyobashi, Chuo-ku, Tokyo

Comments