Explore the Highlights of the Permanent Collection and the Matsukata Collection

Looking for Western art in Japan? Start with The National Museum of Western Art in Ueno!

As you stroll through Ueno Park, you’ll notice a unique and modern-looking building. With no walls on the ground floor, it almost appears to float in the air. This striking structure is home to one of Japan’s best places to enjoy Western art — The National Museum of Western Art.

While the museum regularly hosts high-quality special exhibitions, its true charm lies in the permanent collection.

You’ll find works by Rubens, Rembrandt, Monet, Renoir — yes, the very masterpieces you saw in your school textbooks. First-time visitors are often surprised: “Wait, all these famous works are here?”

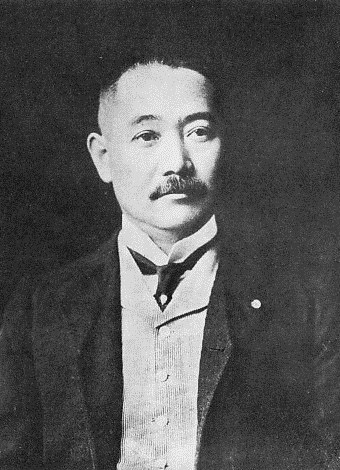

The heart of the collection is the Matsukata Collection, assembled in the early 20th century by Japanese industrialist Kojiro Matsukata. These works were returned to Japan from France after World War II and are now treasured as part of Japan’s cultural legacy. Matsukata’s dream? To build a world-class art museum in Japan — and that dream lives on in this institution.

Famous pieces like Monet’s Water Lilies and Rodin’s The Gates of Hell can be enjoyed in a calm, welcoming setting — no need to rush or feel overwhelmed. The permanent exhibit rotates slightly with the seasons, so there’s always something new to see, even for repeat visitors.

If you’re heading to Ueno, make sure to include this museum in your plans.

Whether you’re an art beginner or a seasoned museumgoer, it offers a peaceful and inspiring experience.

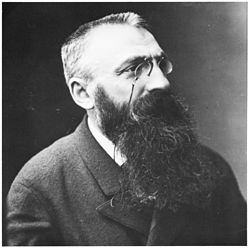

A Museum Born from One Man’s Dream: The Vision of Kojiro Matsukata

The origins of The National Museum of Western Art in Ueno trace back to the vision of one passionate businessman: Kojiro Matsukata.

The museum exists today thanks to the Matsukata Collection, a group of artworks he risked everything to assemble.

Between the 1910s and 1920s, Matsukata collected approximately 8,000 ukiyo-e prints and about 3,000 Western paintings and sculptures. The scale of his private collection was extraordinary — something rarely seen even today.

But tragedy struck.

In 1927, the global financial crisis hit.

Kawasaki Shipbuilding, where Matsukata served as president, faced severe financial trouble, and he was forced to part with many of his treasured works.

What remained — about 1,400 pieces stored in London and Paris — narrowly escaped this first setback.

But more challenges lay ahead.

In 1939, a fire broke out at the Pantechnicon warehouse in London, destroying more than 900 works.

Then, after World War II, the rest of the collection in Paris was seized by the French government.

Nearly all of the artworks Matsukata had poured his soul into collecting were lost.

It’s hard to imagine the heartbreak he must have felt.

img: by Stephen Richards

Matsukata passed away in 1950, without seeing his beloved artworks returned.

But his dream — to build an art museum in Japan that could stand alongside the world’s best — never truly died.

After his passing, his family and the Japanese government continued negotiations with France.

Finally, in 1953, an agreement was reached to return part of the collection.

To house the returned works, a new museum was built — The National Museum of Western Art, which opened in 1959.

Since then, it has been one of the few museums in Japan dedicated exclusively to Western art, beloved by generations of visitors.

Must-See Highlights from the Collection

At its peak, the Matsukata Collection featured around 3,000 Western artworks.

However, due to fire and postwar seizures, only about 370 works made it into the museum’s opening collection in 1959.

Since then, the museum’s holdings have grown significantly through donations and independent acquisitions.

Today, the collection includes over 6,000 works, making it one of Japan’s richest resources for Western art.

Here are just a few of the highlights you can look forward to.

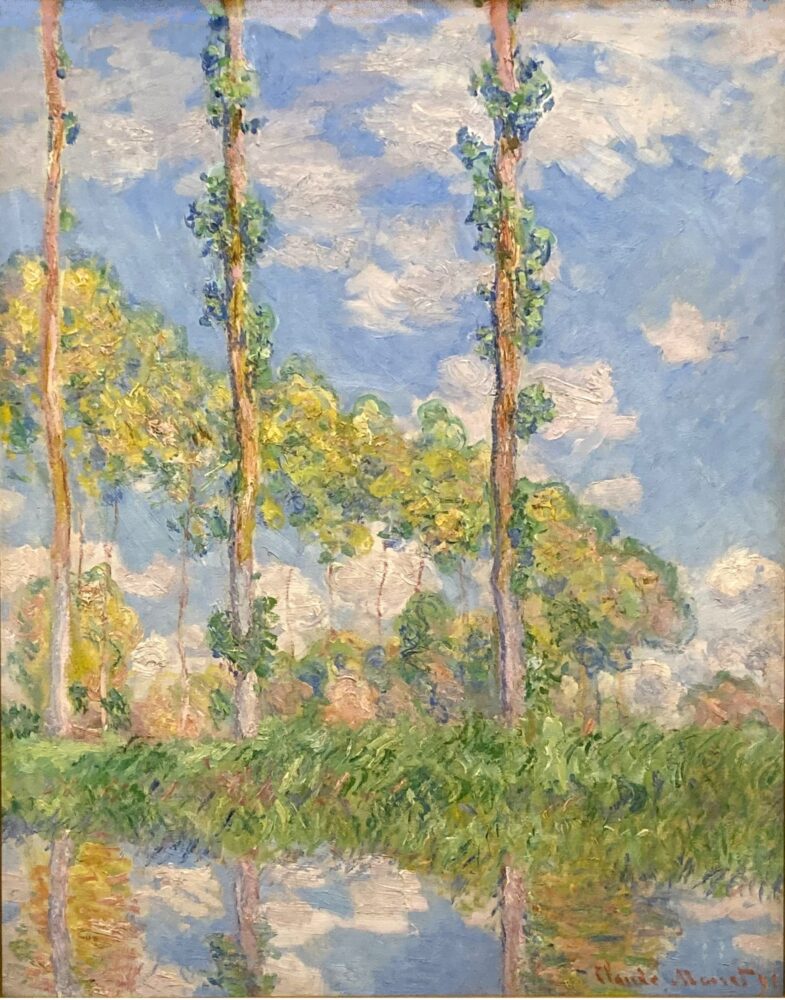

Claude Monet, Poplars in the Sunlight (1891)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Painting That Captures Monet’s Signature Atmosphere

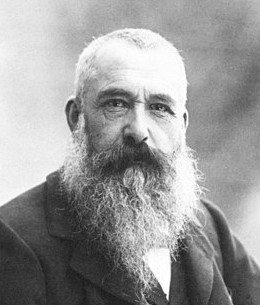

When people think of Claude Monet (1840–1926), many imagine his famous Water Lilies series.

But Monet also created many other series — including this one: Poplars in the Sunlight, which depicts rows of tall poplar trees along the Epte River near his home in Giverny.

In this painting, a deep blue sky stretches across the canvas, while shimmering light reflects off the river’s surface.

The towering poplars in the foreground rise beyond the frame, and a tree-lined path continues into the distance.

But there’s something unusual: the perspective is soft, even ambiguous.

Edges are blurred, and shapes seem to melt into light — a classic Monet technique.

By toning down the details, he brings out the mood and “air” of the scene, letting light take center stage.

You can almost feel the cool shimmer of the water and the gentle rustle of the poplar leaves.

It’s a true “impression,” a moment captured so vividly you might hear the quiet breeze by the riverbank.

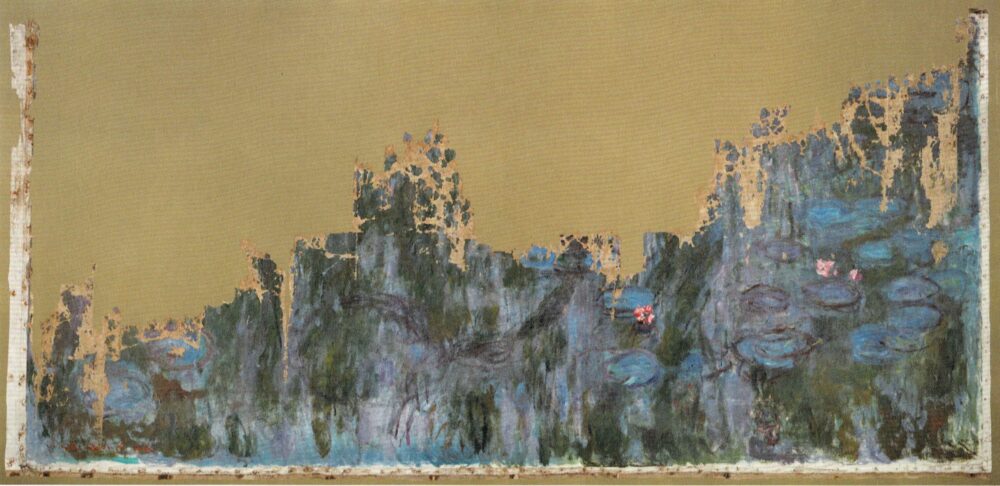

Claude Monet, Water Lilies: Reflection of Willows (1916)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

The Only One of Its Kind — A Legendary Water Lilies Painting Gifted by Monet

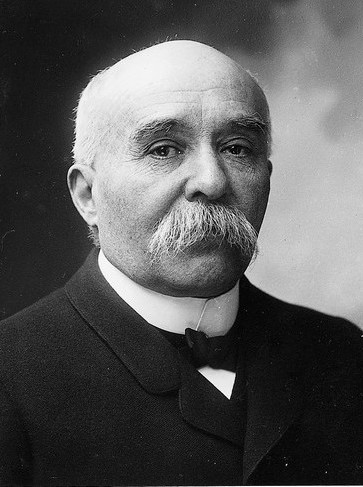

In 1921, Kojiro Matsukata visited Claude Monet in Giverny, France, thanks to an introduction from Georges Clemenceau, a former Prime Minister of France and a close friend of the artist.

During that visit, Matsukata purchased 15 of Monet’s paintings directly from the artist’s studio.

Clemenceau reportedly asked Monet to offer his friend a discount, but Matsukata politely declined.

He is said to have replied, “It would be shameful to turn friendship into money,” and instead handed Monet a check for 1 million francs.

Perhaps moved by Matsukata’s sincerity — or maybe just in one of his famously generous moods — Monet made an extraordinary gesture.

He offered Matsukata a section of his Grand Decorations, a series of large-scale Water Lilies murals meant to cover the walls of an entire exhibition room.

That piece is the one now known as Water Lilies: Reflection of Willows.

At the time, many collectors wanted to buy parts of the Grand Decorations, but Monet turned them all down.

In the end, this was the only piece he ever gave away from the series — making it truly unique in the world.

A Lost Masterpiece That Finally Came Home

Unfortunately, the painting was never shipped to Japan. Instead, it was stored at the Rodin Museum in Paris.

Then came World War II. To protect it from the fighting, the painting was evacuated to a private home in the French countryside.

However, during that time, it suffered water damage and aging-related decay — the top portion of the canvas was severely damaged.

It wasn’t until 2016 — nearly 100 years after Matsukata’s visit — that the work was finally returned to Japan and made available to the public.

Yes, it’s true that part of the painting is missing. But in a way, that damage tells a story:

A story of survival through war and disaster.

A story of Monet’s artistic spirit, Matsukata’s passion for art, and the deep history that connects France and Japan through this one extraordinary canvas.

Interestingly, art historians believe that this painting was originally the central panel of Reflections of Trees, a part of the Grand Decorations series now housed in the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris — the compositions are remarkably similar.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies (1916)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

img: by Spedona

A Pond That Reflects the Sky — and Draws You In

Giverny, a quiet town northwest of Paris, was Monet’s beloved home.

There, he created a stunning “water garden” beside his house — the setting for his famous Water Lilies series.

This Water Lilies painting is one of those works.

Your eyes are first drawn to the clear blue sky reflected on the surface of the pond.

Floating lily blossoms and the reflections of trees mix together, creating a harmony of color — like a visual symphony.

Despite this richness, the painting feels calm and gentle.

The cool tones of the water and the deep colors beneath the surface aren’t precisely detailed, yet they capture the scene’s essence with surprising accuracy.

Monet painted not just what he saw, but what he felt.

The result is a quiet sense of immersion — before you know it, you’re not just looking at the painting, you’re inside it.

img: by World3000

A Painting Worth 800,000 Francs!?

In 1922, Kojiro Matsukata bought another painting directly from Claude Monet.

According to local newspapers at the time, he handed Monet a check for 800,000 francs — about 150 million yen in today’s money (around 1 million USD) — and simply asked him to “choose one painting.” Even for a Monet, this was an extraordinary price in those days.

While there’s no exact record of which painting he purchased, experts believe it was part of Monet’s monumental Water Lilies series, known as the “Large Decorations.” This makes it very likely that the Water Lilies now in the National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo, was the one.

Monet, who was especially fond of Matsukata, may have chosen a true masterpiece for him. And when you see the painting’s stunning detail and atmosphere, it’s easy to believe that story.

Johannes Vermeer (Attributed), Saint Praxedis (1655)

On deposit from a private collector

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Vermeer… in Japan?

Johannes Vermeer — the Dutch master known for quiet, light-filled scenes like The Milkmaid and Girl with a Pearl Earring — is one of the most celebrated painters in art history.

But did you know that a painting attributed to Vermeer is right here in Japan?

That painting is Saint Praxedis.

It’s the only Vermeer work (or possible Vermeer) on display in Japan.

Still, you might wonder at first glance: “Is this really a Vermeer?”

That’s a fair question. The religious subject matter feels quite different from the everyday domestic scenes most people associate with Vermeer.

But there’s more to the story.

In Vermeer’s time, it was common for young artists to make copies of classical masterpieces as part of their training.

Also, Vermeer had recently married into a devout Catholic family, which may explain why this early work carries strong Christian themes.

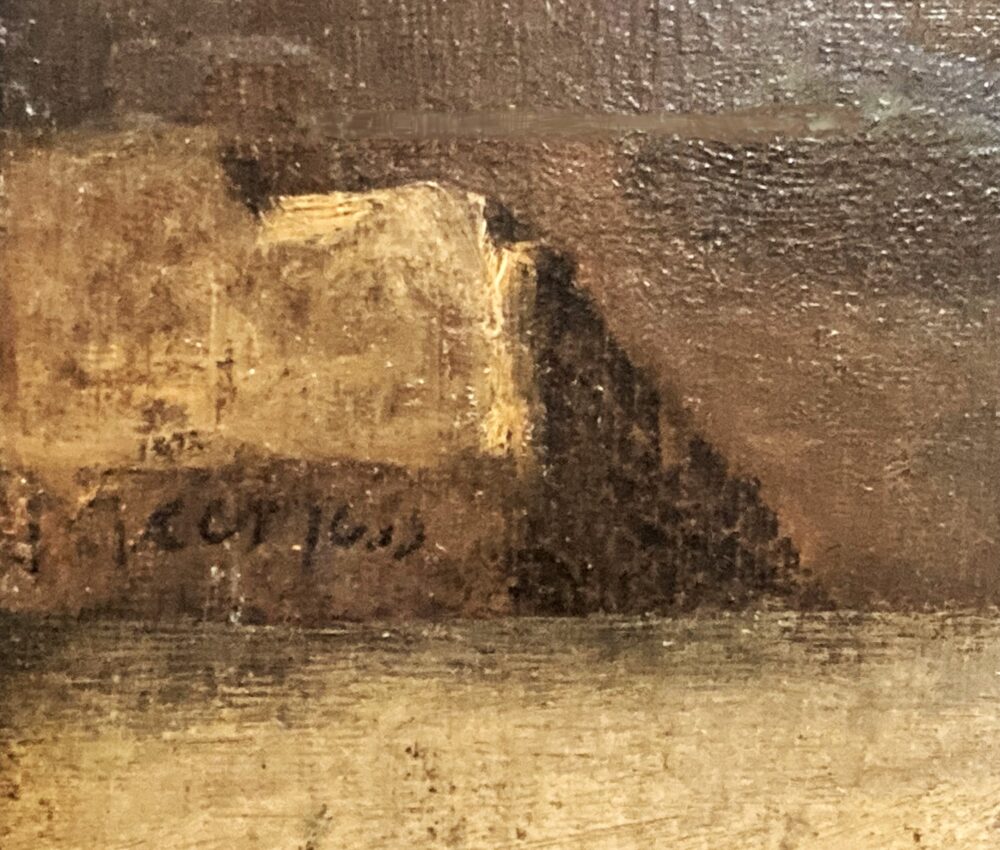

The Signature That Might Change Everything

Look closely at the bottom left corner of the painting — on the stone.

You’ll see a small but important detail:

“Meer 1655”

This is a key piece of evidence.

That signature, written in Vermeer’s characteristic style, has been scientifically dated to the same time the painting was made.

There was little reason to forge a Vermeer signature in the 1600s, since he wasn’t yet a famous or valuable name.

Even more compelling?

Analysis of the pigments shows they are authentic 17th-century Dutch materials — consistent with Vermeer’s known works.

Because of this, many experts now believe this is likely an early work by Vermeer.

In fact, during the massive Vermeer exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam in 2023, this painting was proudly shown as an authentic Vermeer.

A Masterpiece Full of Mystery

That said, there’s still no conclusive proof.

That’s why the museum carefully labels it “attributed to Vermeer.”

But maybe that’s what makes this painting so fascinating.

It lives in the space between certainty and mystery — inviting us to question and imagine.

Whether it’s a true Vermeer or not, Saint Praxedis is a must-see for any art lover visiting Japan.

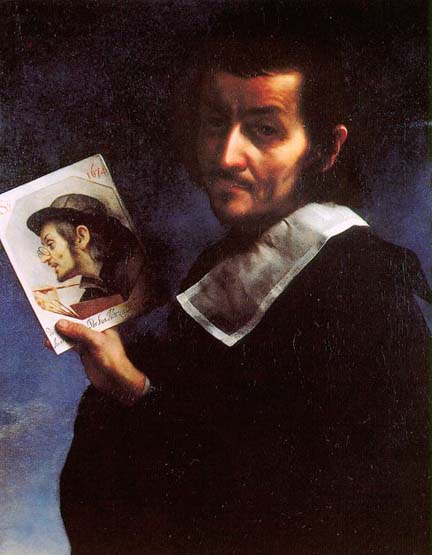

Georges de La Tour, Saint Thomas

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Silent Drama Lit by Candlelight

Georges de La Tour (1593–1652) was a Baroque master known as the “Painter of the Night.”

His signature style? Quiet, candlelit scenes that feel almost sacred in their stillness.

Only about 40 authenticated works by La Tour survive today.

This painting, Saint Thomas, is one of those rare treasures — and you can see it right here in Japan.

The Doubting Apostle, Lost in Thought

The figure shown here is Saint Thomas, one of the twelve apostles of Christ.

He’s best known for the moment when he doubted Jesus’ resurrection — refusing to believe until he touched Christ’s wounds with his own hands.

Thomas was later martyred in India, reportedly pierced by a spear.

That’s why you’ll often see him depicted with a spear — a symbolic item known as an attribute.

In this painting, Thomas quietly stares at the spear he holds.

Is he reflecting on Christ’s suffering? Or is he contemplating his own future death?

His expression is calm, but not empty.

La Tour uses soft light and deep shadow to capture a moment of inner conflict and quiet faith — a “silent drama” playing out in the dark.

Only Two in Japan

There are just two La Tour paintings in Japan.

One is Saint Thomas here at The National Museum of Western Art.

The other, The Smoking Man, is housed at the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum.

Both works are filled with La Tour’s signature tension and stillness.

Take your time with them — these paintings invite you to slow down and really look.

Vincenzo Catena, Madonna and Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Quietly Powerful Renaissance Masterpiece

Vincenzo Catena (c. 1480–1531) was a Venetian painter of the Renaissance.

He’s not a household name today, but he worked alongside greats like Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione, and Titian.

Catena’s early style shows strong influence from Bellini, and around 1510, he began to experiment with Giorgione’s poetic touch.

But what truly makes Catena stand out is his unique approach — simplified forms, soft expressions, and a fresh, almost modern sensibility.

You can see this clearly in Madonna and Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist.

The painting likely dates to around 1512, based on clues like the unfinished facade of the Santa Maria Formosa Church in the background and the historically accurate design of the well.

img: by Didier Descouens

A Painting That Grows on You

At a time when oil painting was becoming more popular, Catena chose to work in tempera — a traditional medium made with egg yolk.

This gives the piece a matte texture and soft, luminous colors, especially noticeable in the faces and fine outlines.

It’s not a flashy painting. But the more you look, the more it draws you in.

Everything feels still — as if time inside the frame has slowed down.

This kind of gentle, thoughtful work reminds us that the true spirit of the Renaissance sometimes lives not in drama, but in subtle beauty.

Carlo Dolci, The Virgin in Sorrow (c. 1655)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

The Slow, Careful Brush of a Baroque Painter

Carlo Dolci (1616–1686) was a Baroque painter active in Florence.

While Baroque art is known for bold contrasts of light and dark, Dolci brought something different to the table: precision and quiet emotion.

He was famously slow — so much so that it was said he once took an entire week just to paint a single foot.

But the results were worth it. His works are so finely detailed that you can hardly see any brushstrokes. People of his time admired him for this almost photographic realism.

The Blue Veil and a Silent Gaze

In The Virgin in Sorrow, Dolci’s skill is on full display.

Look at the softness of the blue veil, the delicate hands, the flawless finish.

But the most striking element? Her face.

You can’t fully see her eyes — they’re partly hidden in shadow. That’s unusual, especially for a religious painting.

And yet, that subtle choice speaks volumes.

By leaving her expression unreadable, Dolci invites us to imagine her grief.

The silence becomes powerful — a quiet sorrow that lingers and resonates with each viewer.

This isn’t just a devotional image.

It feels personal and introspective, like a shared moment of stillness and reflection.

A masterpiece that whispers, rather than shouts — and stays with you long after you’ve walked away.

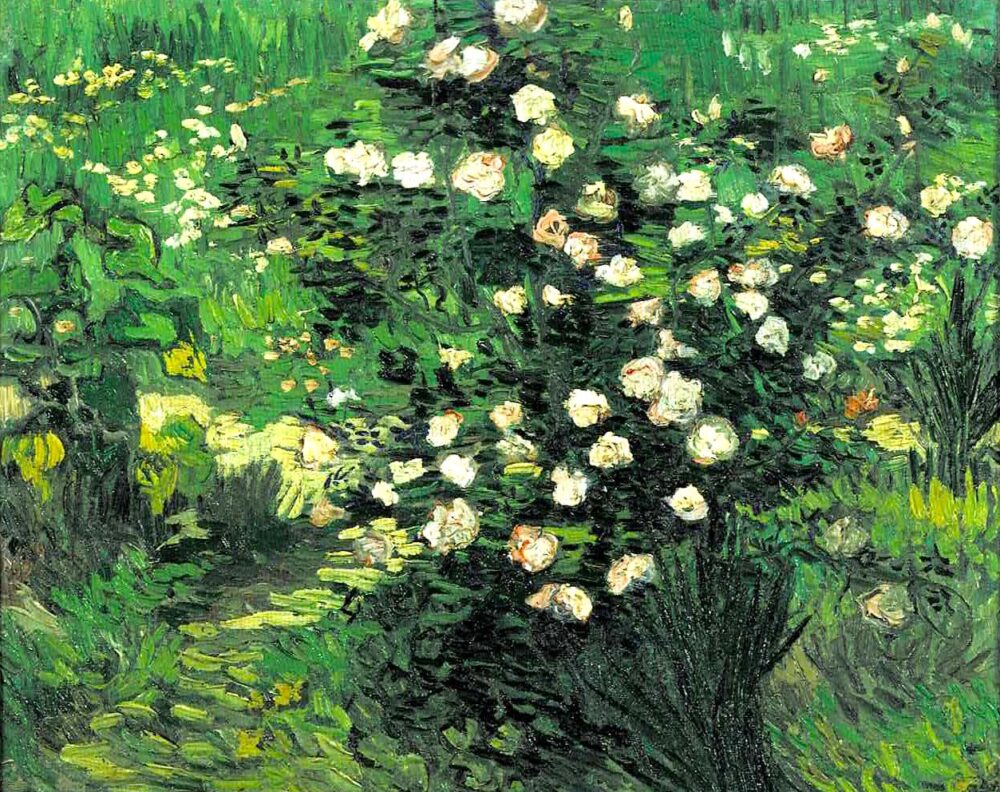

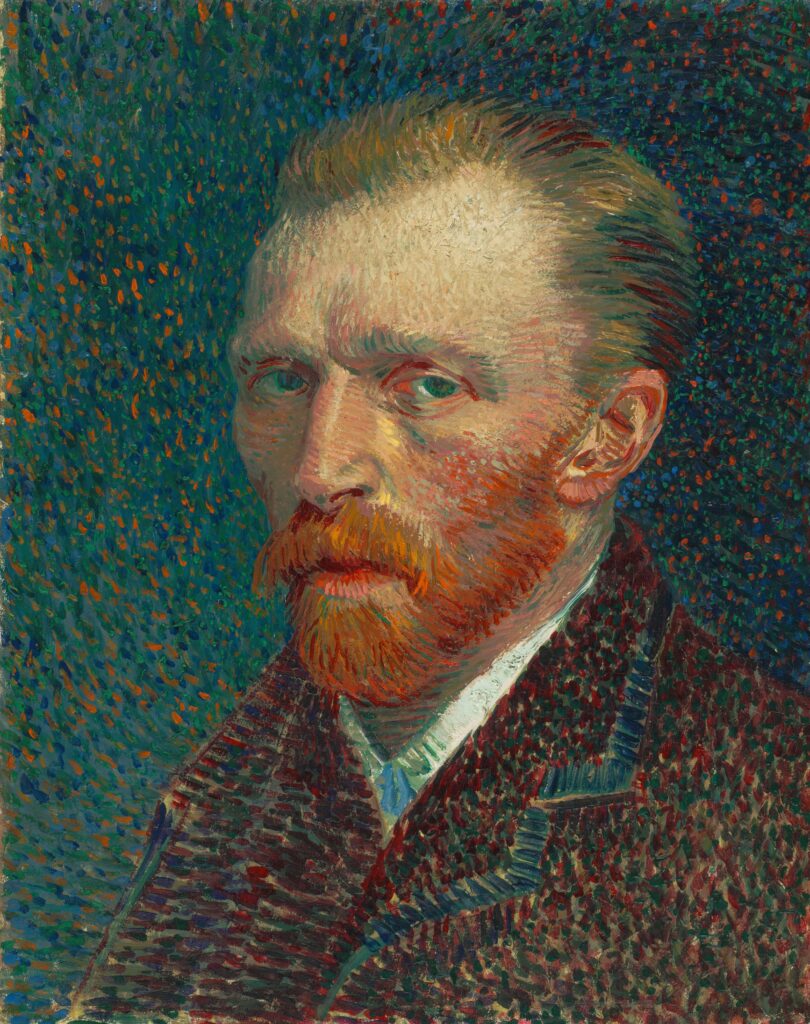

Vincent van Gogh, Roses (1889)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Moment of Peace in the Sanatorium

When people think of Vincent van Gogh, many remember the tragic “ear incident” in Arles, southern France.

After that breakdown, van Gogh admitted himself to a mental hospital in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, hoping to recover both mentally and physically.

Though his art didn’t sell and he struggled deeply, van Gogh never stopped painting.

He turned to nature—flowers, gardens, and the hospital grounds—for healing and inspiration.

This piece, “Roses,” was created during his stay at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum.

It captures one of the small, quiet beauties he discovered during his recovery.

Soft green tones fill the canvas. Pale pink and white roses bloom gently, as if floating in calm air.

Gone are the heavy outlines and bold contrasts seen in earlier works.

Here, van Gogh’s gaze is softer—simply observing, simply painting.

There’s no drama. Just a man and a flower.

This still moment of connection, brush in hand, tells its own quiet story.

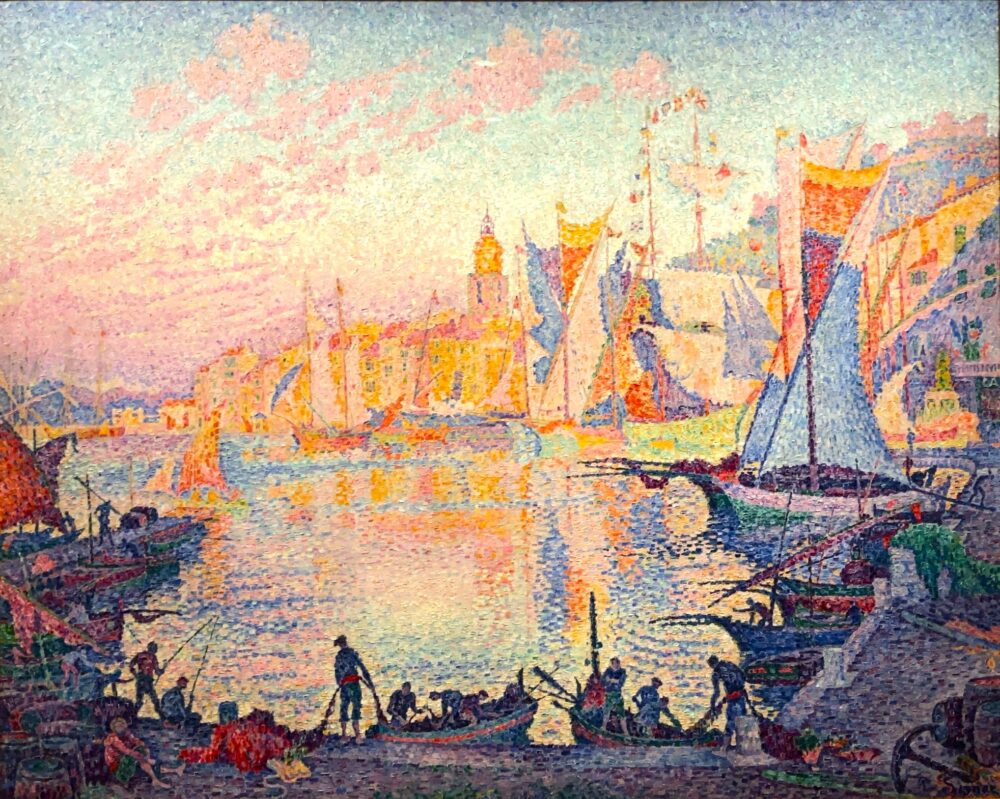

Paul Signac, The Port of Saint-Tropez (1901–1902)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Painting with Color Dots—The Magic of Pointillism

Paul Signac was a key figure in the Neo-Impressionist movement, known for perfecting the art of pointillism—a painting technique that uses tiny color dots to build entire scenes.

Unlike the Impressionists who loosely broke up brushstrokes, Signac and others took a more scientific approach.

They placed pure colors side by side, letting the viewer’s eyes do the mixing.

This large-scale masterpiece, “The Port of Saint-Tropez,” was painted when Signac lived in the colorful harbor town of Saint-Tropez in southern France.

Up close, it’s all dots—hundreds of tiny touches of pink, blue, green, and gold.

But from a short distance, a whole scene emerges: boats, buildings, calm waters, and soft Mediterranean light.

It feels like early morning… or just before sunset.

Each color changes depending on what surrounds it.

A pink next to deep blue pops. The same pink next to light blue blends in softly.

It’s as if the colors are talking to each other—a beautiful, visual conversation.

img: by Ballista at English Wikipedia

Maurice Denis, Dancing Women (1905)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Beyond Realism: Maurice Denis and the Nabis

Maurice Denis was a key member of the Nabis, a group of artists active in late 19th-century Paris.

Unlike traditional painters who focused on realism, the Nabis emphasized symbolism, mysticism, and the emotional meaning behind their art.

Denis and his fellow artists were inspired by Paul Gauguin’s philosophy, blending color, form, and feeling into their work in ways that were bold and new.

The Influence of Japanese Ukiyo-e

One of the biggest inspirations for the Nabis was Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

They were drawn to the flat compositions, strong outlines, and decorative approach—so different from the traditional Western use of perspective and shading.

You can clearly see this influence in Dancing Women.

The tall vertical canvas almost feels like a hanging scroll.

The color palette is soft—mainly pale blue, green, and white, with touches of gentle purple.

Outlines are bold, and the shadows are not blended but expressed through flat color areas.

The painting is richly decorative, yet incredibly quiet.

It captures a moment where time seems to pause as the women dance in stillness.

This use of outlined color fields was rare in Western painting at the time. It later became known as Cloisonnism, a post-impressionist style that slowly gained attention in the early 20th century.

For many Japanese viewers, Denis’s work might feel strangely familiar.

This style—so common in ukiyo-e and even modern manga—makes his paintings feel both exotic and oddly close to home.

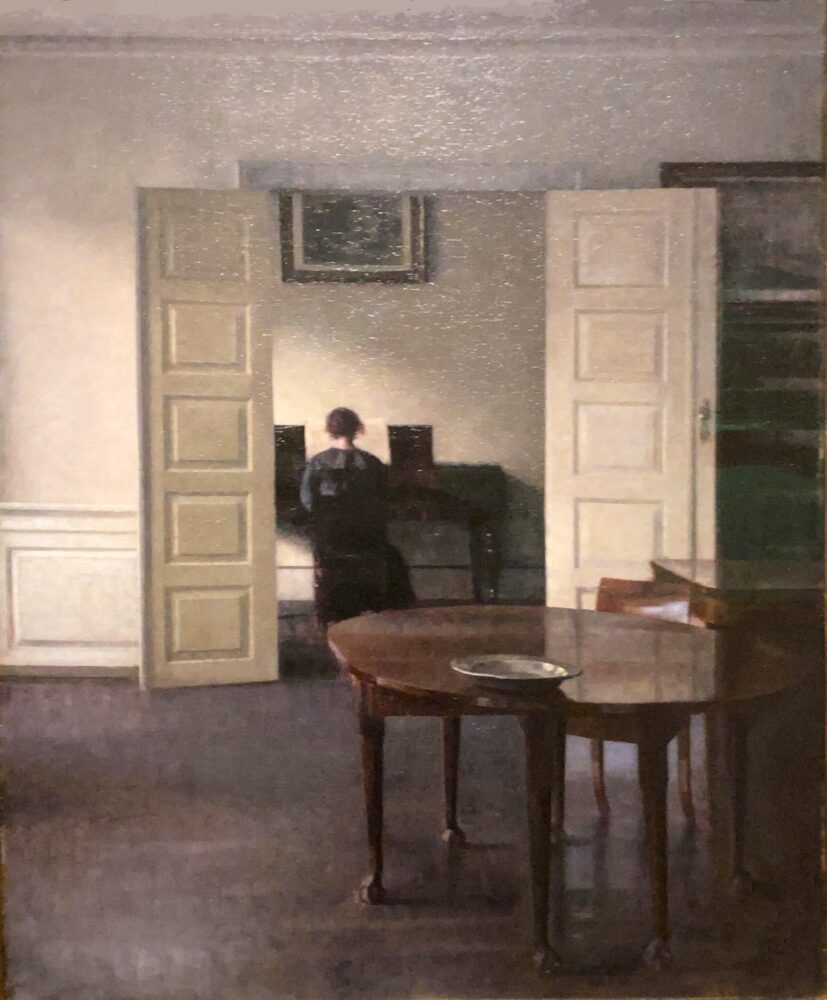

Vilhelm Hammershøi, Interior with Ida Playing the Piano (1910)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

The Art of Silence: Finding Depth in Simplicity

Vilhelm Hammershøi was a Danish painter best known for his quiet, minimalist interior scenes.

His works are the complete opposite of flashy or dramatic—they invite viewers to slow down and listen to the silence.

In Interior with Ida Playing the Piano, we see a room in his Copenhagen apartment on Strandgade Street, where he spent his final years.

At first glance, the room seems almost empty.

There’s a piano, a table, and a single silver dish in the back room—no decoration, just space and stillness.

This carefully reduced atmosphere creates a sense of peaceful emptiness.

Facing the piano is a woman seated with her back turned.

She is Ida, Hammershøi’s wife and frequent model.

True to his style, her face is not shown. Hammershøi rarely painted expressions, focusing instead on presence and mood.

A Quiet Human Presence

There’s no clear story here—no drama, no emotion on display.

Yet the image feels deeply human.

A person is simply there, sitting in a quiet room, and that simple fact holds immense emotional power.

Hammershøi’s paintings often have no words, no action—but they are full of presence.

Viewers are invited to walk through the silence, noticing the light, the space, and the faint trace of human life.

Each person may take something different from the experience.

His work seems to echo the viewer’s own sense of quiet—offering not answers, but stillness.

Auguste Rodin, The Gates of Hell

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Did You Know The Thinker Was Part of a Giant Gate?

When people think of Auguste Rodin, The Thinker is probably the first sculpture that comes to mind.

But here’s something surprising—The Thinker was originally just one part of a much larger work called The Gates of Hell.

Rodin was commissioned in 1880 to design the entrance for a new museum of decorative arts in Paris.

He based his concept on Dante’s Inferno from The Divine Comedy, imagining a dramatic “gate to hell.”

The Thinker, sitting at the top of the gate, may represent Dante himself, or even Rodin in deep contemplation.

Rodin developed his idea using clay models, watercolors, and sketches.

But when the museum project was canceled in 1888, the gate remained unfinished.

Even so, Rodin kept working on it and presented a plaster version at the 1900 Paris World’s Fair.

The bronze casting was completed only after his death.

And who ordered the first bronze cast?

Kojiro Matsukata, a Japanese art collector and industrialist.

Only 7 in the World—And You Can See One in Ueno for Free

Today, only seven bronze versions of The Gates of Hell exist in the world.

One of them stands proudly in the front garden of the National Museum of Western Art in Ueno, Tokyo.

Standing 5.4 meters tall and 3.9 meters wide, it’s an overwhelming and unforgettable sight.

Best of all? It’s on outdoor display—so anyone can see it for free, no museum ticket required.

Look closely and you’ll notice over 180 sculpted figures covering the surface.

They twist, cry, and writhe in torment, representing the lost souls of hell.

At the top, The Thinker sits quietly, lost in thought—a powerful contrast to the chaos below.

When you visit Ueno, be sure to pause in front of this massive bronze gate.

Take a moment to study the details.

Even though the work was never officially finished, its intensity and emotion are still very much alive over 100 years later.

And who knows—you might find yourself becoming a “thinker” too, reflecting on the meaning Rodin poured into this incredible creation.

Before You Go: The Joy of the Permanent Collection at the National Museum of Western Art

There’s more to the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo than just its special exhibitions.

One of its biggest highlights is the museum’s high-quality permanent collection, carefully built over time and dedicated entirely to Western art.

At the heart of this collection is the famous Matsukata Collection, started by Japanese businessman Kojiro Matsukata.

Although many works were lost during war and natural disasters, Matsukata’s dream—

to bring great Western art to Japan—lives on today through the museum.

The museum now holds over 6,000 pieces, spanning a wide range of styles and time periods.

Its collection is one of the most impressive in Japan, both in size and quality.

The permanent exhibition space is spacious and peaceful, offering a truly rich experience—on par with any temporary show.

And the best part? You can enjoy these masterpieces year-round, at your own pace and in a calm, quiet setting.

What we introduced here is just a small part of what the museum has to offer.

Many more incredible artworks are waiting for you.

If even one piece caught your attention,

why not plan a visit and see it for yourself?

There’s something powerful about standing in front of real art—something that simply can’t be felt through a screen.

Visitor Information: The National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo

Address: 7-7 Ueno Park, Taito-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Comments