Explore a stunning collection of French art—like walking through an art history textbook.

Located in Shin-Sakae, Nagoya, the Yamazaki Mazak Museum of Art is run by Yamazaki Mazak Corporation, a global manufacturer of machine tools. It may sound like an unusual pairing—high-precision machinery and fine art—but this museum offers a truly impressive experience.

By the way, “Mazak” is a name created to make “Yamazaki” easier to pronounce internationally. It eventually became the company’s brand name.

Now, back to the museum itself. The museum focuses mainly on its permanent collection, with paintings displayed on the 5th floor and glass art and antique furniture on the 4th floor. Please note that during special exhibitions, some displays may temporarily change.

The painting collection is remarkably rich. Starting with Rococo masters like François Boucher and Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, the museum takes you through Neoclassicism (Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres), Romanticism (Eugène Delacroix), Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and even early 20th-century modern art. From Gustave Courbet and Pierre Bonnard to Maurice Denis, you’ll get a sweeping view of French art from the 18th to the 20th century. It truly feels like stepping inside an art history book.

See the Masters Up Close—No Glass or Acrylic Barriers

One detail that really stands out: the paintings aren’t covered with acrylic or glass panels. Oil paintings often reflect light, making it hard to enjoy the details unless you view them from an angle. But here, there’s nothing between you and the artwork. This thoughtful design lets you appreciate each piece head-on, without distractions—a rare and deeply satisfying way to experience great art.

Featured Works in the Collection

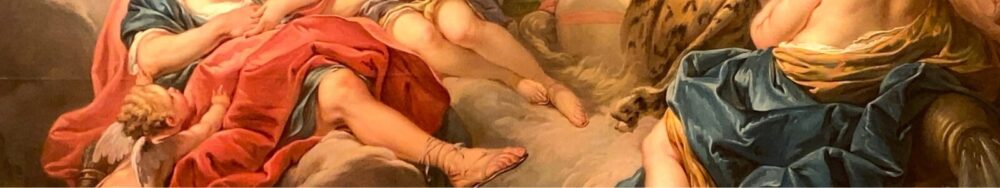

François Boucher, “Aurora and Cephalus “ (c.1745)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Shining Example of Rococo Elegance

One of the highlights of the Yamazaki Mazak Museum is this large-scale masterpiece by François Boucher. Even if you’ve never heard his name, you’ve likely seen his style—bright, sweet, and full of charm, it defines the Rococo era.

François Boucher was one of the most celebrated painters of 18th-century French Rococo. He became famous as the favorite artist of Madame de Pompadour, the official mistress of King Louis XV. Boucher was incredibly prolific, creating over 1,000 works, including portraits, mythological scenes, and decorative paintings for royal palaces.

by François Boucher (Collection of the Alte Pinakothek)

This painting, Aurora and Cephalus, is a stunning example of his mythological works. The subject comes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In the story, Aurora, goddess of dawn, tries to seduce the handsome mortal Cephalus—but he refuses her, remaining faithful to his wife, Procris.

But in Boucher’s version, there’s no sign of inner struggle. Instead, the two figures are peacefully bathed in soft morning light, exuding grace and serenity. This dreamy interpretation captures the very essence of Rococo art—favoring beauty and atmosphere over realism or moral conflict. It reflects the tastes of the French court, where elegance mattered more than drama.

And don’t miss the scale of this piece—it’s huge! At nearly 2.4 meters tall and over 2.5 meters wide, it’s a powerful presence. Luckily, the museum’s 5-meter-high ceilings give it plenty of space to breathe. You can enjoy the painting from a distance or step closer to admire the details. The exhibition space feels tailor-made for the work, enhancing the overall experience.

Eugène Delacroix, “The Sibyl with the Golden Branch“ (1838)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Quiet and Mysterious Side of Romanticism

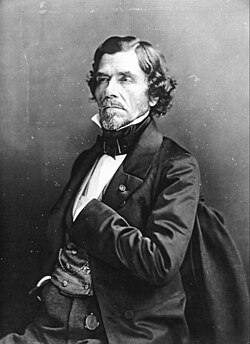

Best known for bold and dramatic works like Liberty Leading the People and The Massacre at Chios, Eugène Delacroix was a leading figure in the Romantic movement. His paintings often overflow with emotion—passion, chaos, sorrow.

But Delacroix also had a quieter, more introspective side. The Sibyl with the Golden Branch is a perfect example of that mood. Based on a scene from Book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid, the painting captures a mystical moment as the hero Aeneas prepares to enter the underworld.

With the help of the prophetess Sibyl, Aeneas must find the “Golden Bough,” an offering to the goddess Proserpina—the key to gaining entrance to the realm of the dead. It’s a moment filled with tension, silence, and a sense of the unknown.

This painting might surprise you if you’re used to Delacroix’s more intense scenes. Here, the composition is simple, but the symbolism and quiet intensity are striking. At the center stands the Sibyl, dressed in red, her gaze calm and otherworldly. Behind her lies a dark forest—an eerie threshold to the underworld. A faint path in the background hints at the journey that’s about to begin.

Mystery and Stillness at the Edge of the Underworld

The Sibyl’s composed expression and solemn presence make her feel more divine than human. The overall atmosphere is heavy with shadow and silence, as if time has slowed just before a great trial begins.

There’s no flashy action, but the colors—deep reds, dark shadows, and glints of gold—are pure Delacroix. The contrast gives the scene a timeless, sacred feel.

This painting captures a moment of pause before crossing into the unknown. The more you look, the more you feel drawn into its quiet power.

Gustave Courbet, “The Wave Rough Sea at Dusk” (1869)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

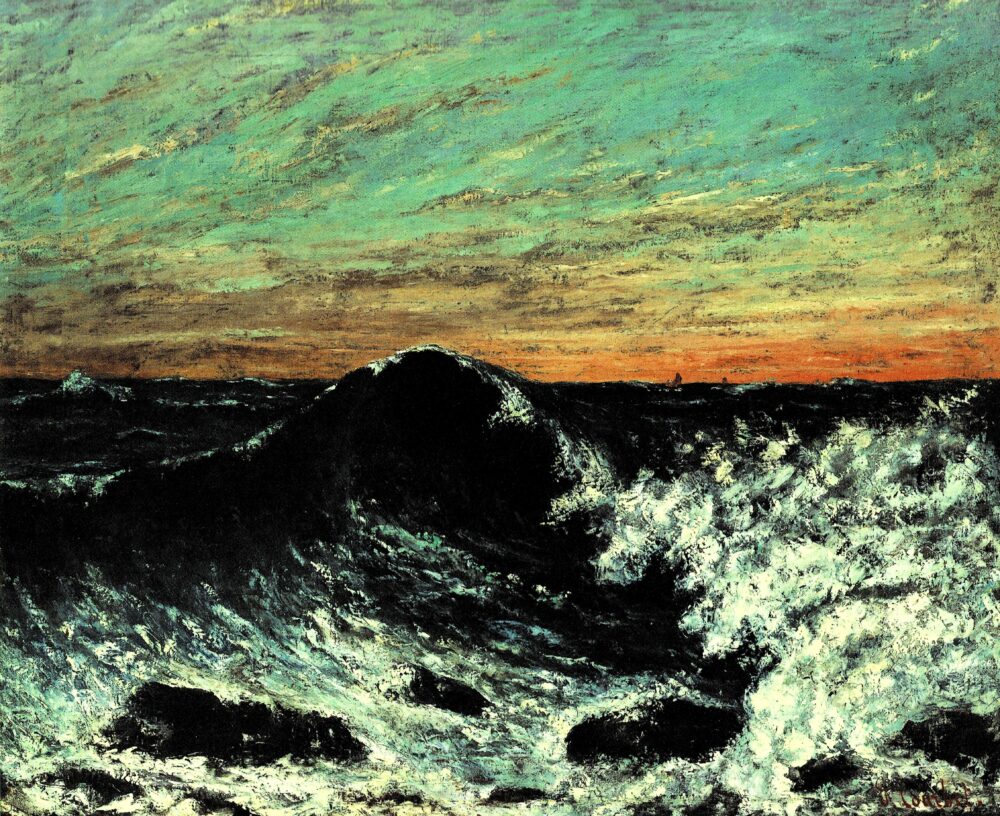

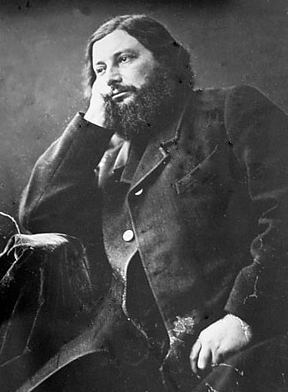

Courbet the Realist: Painting Only What He Could See

Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) was a leading figure of Realism, a movement that rejected idealized or mythological subjects in favor of real, visible life. He famously said, “I have never seen an angel. Show me an angel and I will paint one.” This summed up his belief in portraying only what could be directly observed.

Courbet gained attention for his large-scale paintings of peasants and workers, becoming a pioneer of socially conscious realism. But in his later years, he turned away from people and focused on nature—especially the sea.。

Realism in the Waves

“The Wave Rough Sea at Dusk is one of Courbet’s late seascapes. Dominating the canvas are dark, powerful waves that look as if they might collapse at any moment. White foam crashes against the rocks in the foreground, while the sky in the distance glows faintly with the last light of sunset.

Courbet’s signature heavy brushwork and deep colors give the waves a sense of real weight and movement. Look closely at the sky—he used a palette knife to scrape away paint, revealing the underlayer and creating a rough texture. This bold technique, especially in the background, is unusual but adds tension that complements the crashing waves in front.

This isn’t just a picture of the sea—it feels like the sea is coming right at you. Before the Impressionists explored movement and light, Courbet was already painting dynamic, emotionally charged oceans.

The scene depicts the Normandy coast—wild, moody, and quiet in a distant, untouchable way. You can sense Courbet’s deep fascination with nature and his lifelong commitment to asking, “What does it mean to be real?”

Claude Monet, “The Port of Amsterdam“ (1874)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

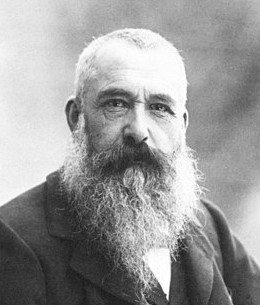

Light on Water: A Quiet Masterpiece from the Birth of Impressionism

In 1874, the first Impressionist exhibition shocked the art world. One of the standout works was Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise, which gave the movement its name. That same year, he painted The Port of Amsterdam.

This peaceful harbor scene captures boats at rest, hazy skies, and shimmering reflections in the water—all rendered with Monet’s signature soft brushwork. Light dances across the surface, giving the painting a calm but radiant energy.

Interestingly, there’s no record of Monet visiting Amsterdam in 1874. He had spent time in the Netherlands in 1871, avoiding the Franco-Prussian War draft, so it’s likely he painted this work later based on earlier sketches or memories.

Nature and Outdoor Light

Monet loved painting water. He even had a studio boat so he could observe how light moved across the surface of rivers and lakes. His lifelong pursuit was not just painting light, but understanding how nature revealed itself through light and color.

In his later years, this passion culminated in his famous Water Lilies series. But in earlier works like The Port of Amsterdam, you can still feel the simple joy of observation. It’s not yet the work of a “great master,” but of a curious artist still discovering how to capture the poetry of nature.

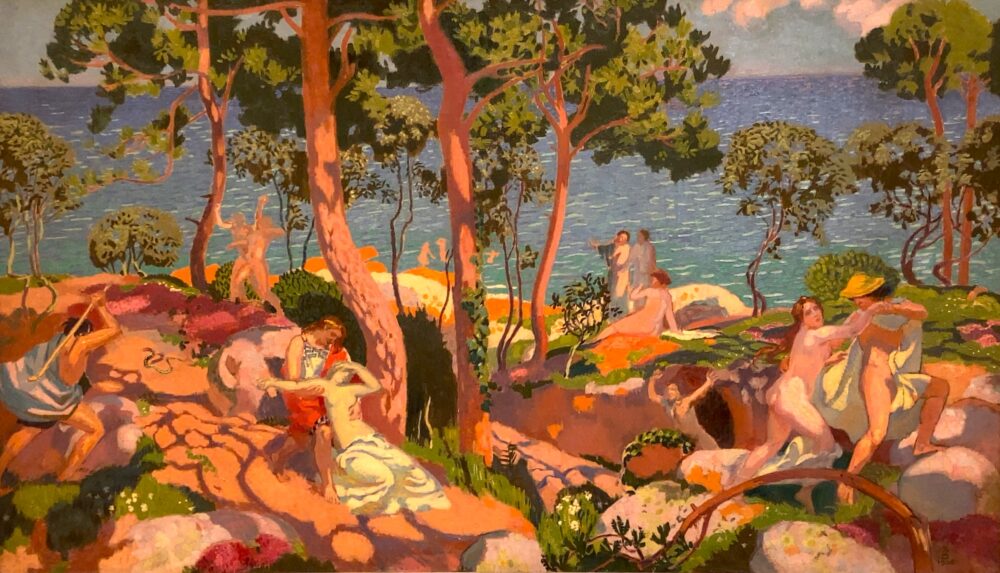

Maurice Denis, “Eurydice“ (1906)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Colorful and Decorative: A Myth Reimagined by Maurice Denis

Maurice Denis (1870–1943), a member of the Nabi group, is known for his bold statement: “A painting is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.” His works often reflect this idea through decorative, flat areas of color, combined with spiritual or mythological themes.

This painting, Eurydice, shows his unique blend of symbolism, emotion, and design. It gently retells the tragic Greek myth of Orpheus and his wife Eurydice with soft colors and a calm, almost dreamlike touch.

Two Moments, One Painting: Time Flowing Across the Canvas

In the myth, Eurydice dies from a snake bite. Her husband, the poet Orpheus, travels to the underworld to bring her back to life. The gods agree—on one condition: he must not look back at her until they return to the surface. But just before they reach the exit, Orpheus turns around. And in that instant, Eurydice is lost forever.

In Denis’s painting, you can see both key scenes from the story within the same frame. In the lower left, Orpheus holds the lifeless Eurydice. On the far right, the same Orpheus is shown turning back in regret.

This storytelling method—showing the same person twice in one scene—is called “simultaneous narrative”. It was common in Japanese picture scrolls and medieval European art, but is rarely seen in modern Western painting.

A Timeless Scene That Blends Classic and Modern

Despite its mythological subject and classical structure, this painting doesn’t feel overly dramatic. The vibrant colors, gentle lines, and serene seaside setting create a peaceful atmosphere. Without knowing the title, you might not even realize this is a tragic love story.

That subtlety may be Denis’s intention. By downplaying the emotion, he draws more attention to the decorative design and composition. While rooted in tradition, the painting also explores new artistic ideas—blending the old and the new in a uniquely beautiful way.

This is a work that reflects Denis’s ongoing question: How can beauty evolve while honoring the past?

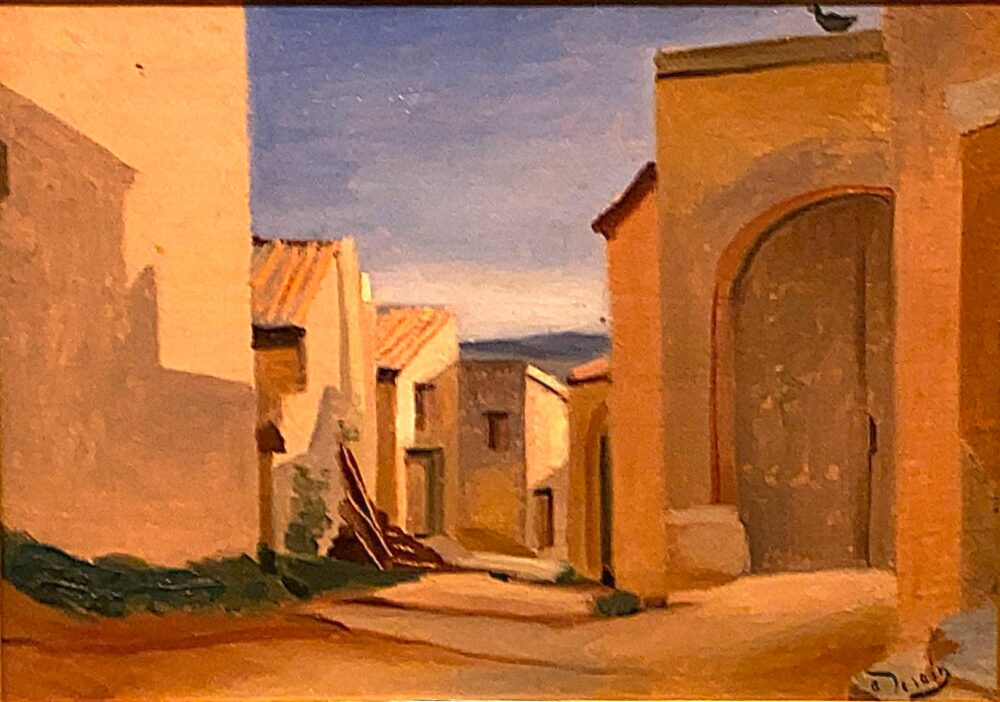

André Derain, “Village in Provence“ (1930)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

From Wild Color to Quiet Harmony: The Evolution of André Derain

André Derain was a founding figure of Fauvism, known for explosive color and bold, energetic brushstrokes. Alongside Henri Matisse, he helped redefine modern art in the early 1900s.

But in this 1930 painting, Village in Provence, that wild energy has given way to calm and balance. The bright hues and chaotic forms are gone, replaced by soft tones and a peaceful village landscape.

From Fauvist Fire to Classical Balance

After his Fauvist years, Derain’s style gradually shifted. Influenced by Neo-Impressionist pointillism, the structure of Cézanne, and even Cubism, his work began to reflect more control, order, and refinement.

In the 1910s and 1920s, Europe’s art world turned toward classicism and harmony—a movement often called “Return to Order.” Derain followed this trend, creating serene landscapes and portraits rooted in traditional forms.

Village in Provence perfectly captures this next phase of his career. The buildings, bathed in the warm light of southern France, are drawn with simple shapes and sculptural presence. The earthy color palette, gentle light, and rhythmic blocks of shadow give the painting a quiet musicality.

A Small Painting with a Strong Presence

Though modest in size, the painting invites you in. Its calm atmosphere, subtle structure, and modern-classical blend reflect Derain’s mature style. It’s a peaceful, reflective work that shows how even a former Fauvist “wild beast” could find beauty in restraint.

A Peaceful Luxury: Experiencing Fine Art at the Yamazaki Mazak Museum of Art

Tucked away in central Nagoya, the Yamazaki Mazak Museum of Art offers a quiet, immersive escape—perfect for anyone who wants to slow down and truly connect with art.

This museum focuses on 18th to 20th century French paintings, featuring world-famous artists like Boucher, Delacroix, Denis, Courbet, Monet, and Derain. It’s like stepping into an art history textbook—but in a calm, intimate setting.

One special feature here is the lack of acrylic or glass covers on the paintings. That means no glare, no reflections—just a clear, direct view of each masterpiece. This rare setup creates a truly personal and distraction-free viewing experience.

On the 4th floor, you’ll also find beautiful Art Nouveau glassworks by masters such as Émile Gallé and the Daum brothers. These delicate vases and lamps are stunning examples of late 19th-century decorative art, offering a different kind of visual pleasure—focused on light, texture, and craftsmanship.

Whether you’re a seasoned art lover or just a curious traveler looking for something inspiring, this museum is well worth a visit. It’s a perfect place to spend a quiet hour—or an afternoon—getting lost in beauty.

Yamazaki Mazak Museum of Art: Visitor Information

Location: 1-19-30 Aoi, Higashi-ku, Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture, Japan

Comments