Located in Kofu City, Yamanashi Prefecture, the Yamanashi Prefectural Art Museum is a special place often called “The Museum of Millet.”

It’s famous for having the most extensive collection of works by the French painter Jean-François Millet in Japan.

Millet is best known for masterpieces such as The Gleaners and The Sower, which beautifully capture the daily lives of farmers.

If you’re drawn to his quiet, heartfelt depictions of rural life, this museum is a must-visit. Here you can see Millet’s iconic work The Sower (1850), along with oil paintings, sketches, and prints.

Walking through the galleries feels like stepping into the pages of an art book dedicated entirely to Millet.

But Millet isn’t the only highlight here.

The museum also features works by other Barbizon School painters, including Rousseau, Troyon, Daubigny, and Corot — artists who left Paris to paint the natural beauty of the countryside.

Their poetic landscapes deeply influenced the later Impressionist movement.

While their colors may be soft and their scenes quiet, these works have a calming power that draws you in.

If you take a moment to look closely, you’ll feel a peaceful stillness — that’s the true charm of landscape painting, and this museum lets you rediscover it.

The Museum in the “Art Forest Park”

Millet and the Yamanashi Prefectural Art Museum

The Yamanashi Prefectural Art Museum opened in 1978, but one year earlier — in 1977 — the museum made a bold investment.

It purchased two of Millet’s major works, The Sower and The Return of the Flock, at a New York auction for 182 million yen (about 1.8 million USD at the time).

Some critics questioned the high price back then, but looking back, it was a brilliant decision.

In fact, by 2014, one of Millet’s pastel works sold for nearly $1.98 million, proving how valuable the museum’s early purchase was.

Since then, the museum has continued to expand its collection, now holding around 70 works by Millet.

Today, it proudly stands as one of Japan’s leading museums dedicated to Millet, drawing art lovers from across the country and beyond.

Who Was Jean-François Millet?

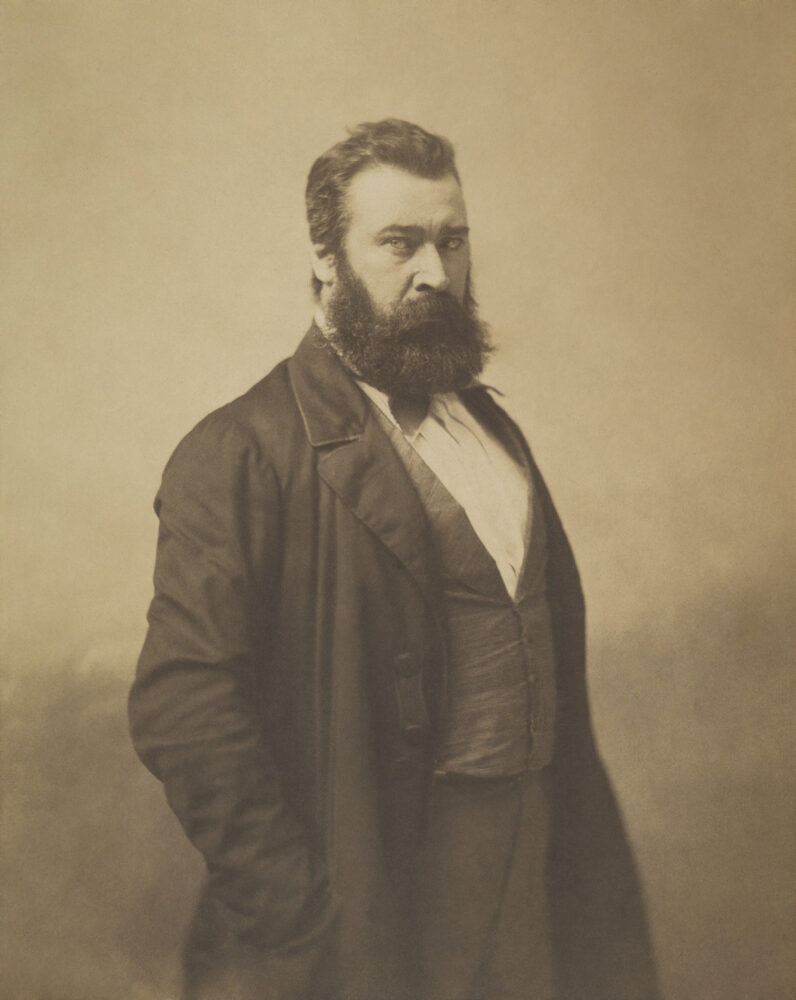

Jean-François Millet was a French painter active in the 19th century and one of the leading figures of the Barbizon School.

During Millet’s time, Europe was in the middle of the Industrial Revolution. Cities were growing rapidly, and the middle class was on the rise.

Art was changing too — instead of complex religious or historical paintings, people began to appreciate landscapes and scenes from everyday life that felt more relatable and human.

Millet’s contemporaries included Gustave Courbet, known for his bold political realism, and Camille Corot, famous for his lyrical landscapes.

But Millet stood apart. His focus was on the lives of farmers — men and women working the land, sowing seeds, and living with quiet strength and dignity.

In Millet’s paintings, peasants are not just part of the landscape; they are the heart of it.

He portrayed their hard work, faith, and perseverance with deep respect.

Though his scenes may seem simple, they carry a profound sense of humanity and timeless beauty.

The Power and Meaning of The Sower

Oil on canvas, 101 × 80.7 cm

Collection of the Yamanashi Prefectural Art Museum

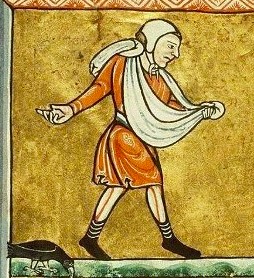

Among Millet’s masterpieces, The Sower stands out as one of his most powerful and iconic works.

Although the colors are dark and subdued, the figure of a farmer striding across the field commands attention.

With each step, he casts seeds into the soil, his movement full of life and determination — almost sacred in its quiet strength.

Today, this painting is loved around the world, but when it was first shown at the Paris Salon in 1850, opinions were sharply divided.

Many upper-class viewers and conservative critics dismissed it as “too rustic” or even “unworthy of fine art.”

At that time, grand themes like mythology and history were still seen as the ideal subjects for painting.

By portraying a simple peasant — someone from the lowest social class — as a heroic figure, Millet challenged the norms of 19th-century art.

img: from wikimedia commons

Yet, The Sower also became a symbol of hope and labor for many intellectuals and republicans of the time.

To them, Millet’s farmer represented the strength and dignity of the working class — a quiet revolution on canvas.

Still, Millet’s true goal was not political.

He wanted to show the honest beauty of people who live close to the earth.

Covered in dust and working in silence, his peasants reflect the timeless human spirit — a reminder that there is deep beauty in everyday labor.

Even today, The Sower continues to speak to us with that same enduring power.

Which One Is the Real “Salon Version”? | The Mystery of Millet’s Two Sowers

Did you know there are five different oil versions of The Sower by Jean-François Millet?

Among them, two are especially famous — the one at the Yamanashi Prefectural Art Museum in Japan (often called the “Yamanashi version”) and the one at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (the “Boston version”).

Both paintings share almost the same composition and were created around the same time, which has sparked debate among art historians for decades.

The biggest question is:

Which version was actually exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1850, where Millet first presented The Sower to the public?

Was it the Yamanashi version or the Boston version?

Surprisingly, no definitive records remain — the mystery has never been solved.

Both museums claim their painting is the true Salon version.

At Yamanashi Prefectural Art Museum, X-ray analysis revealed traces of an earlier composition underneath the surface of their painting — one that closely resembles the Boston version.

This suggests Millet may have painted the Boston version first, then created the Yamanashi version afterward.

In addition, Millet’s close friend and biographer Alfred Sensier wrote that “the version exhibited at the Salon was the second one,” further supporting Yamanashi’s theory that their painting was the one shown in 1850.

img: by Omar David Sandoval Sida

However, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston offers a different argument.

They point out that when Sensier sold the Yamanashi version to the art dealer Durand-Ruel in 1873, he never mentioned that it had been exhibited at the Salon — something he surely would have done if it increased the painting’s value.

Since Sensier was known to be quite shrewd with money, the Boston museum believes this silence indicates the Boston version was the one displayed at the Salon.

In the end, there’s no conclusive evidence on either side.

More than 150 years later, the truth remains a mystery.

But perhaps that’s part of the charm — both versions of The Sower have their own history, beauty, and enduring power that continue to fascinate art lovers around the world.

What Kind of Seeds Is the Farmer Sowing? | Could It Be… Buckwheat?

Have you ever wondered what kind of seeds the farmer in Millet’s The Sower is scattering?

Many art historians believe the painting was inspired by the “Parable of the Sower” from the Bible.

In this story, Jesus tells of a farmer who scatters seeds in different places — on the path, on rocky ground, among thorns, and on fertile soil.

Only the seeds that fall on good soil grow and bear fruit.

In the parable, the seeds symbolize the Word of God, the farmer represents the one who spreads it, and the soil stands for people’s hearts.

Because of this background, most people assume the farmer in Millet’s painting is sowing some kind of grain — probably wheat.

But look closely, and you might notice something interesting.

The farmer seems to be sowing on a slope, not on flat land.

Although Millet painted The Sower while living in Barbizon, the landscape resembles his hometown of Gréville-Hague in Normandy, a coastal area known for its steep cliffs.

And what crop grows well on such sloping, rocky land?

Buckwheat.

It thrives in poor soil and cold climates, and in Normandy it was considered an important crop for local farmers.

In fact, Millet later painted The Buckwheat Harvest: Summer (1868–1874), showing his connection to this humble plant.

That’s why some researchers suggest that the seeds in The Sower might actually be buckwheat.

Of course, Millet never confirmed this himself, so it remains just a theory.

Still, it’s fascinating to think that by choosing buckwheat—a “poor man’s crop” at the time—Millet may have subtly criticized the values of the wealthy bourgeoisie.

Collection of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Interestingly, Yamanashi Prefecture, where this painting is housed today, is also famous for its buckwheat noodles, soba.

In fact, Yamanashi is believed to be the birthplace of soba-kiri, the sliced noodle form of buckwheat we eat today.

So perhaps it’s no coincidence that Millet’s The Sower found a home in Yamanashi — a place that shares such a deep connection with buckwheat and the spirit of the land.

Other Highlights from the Collection

The Yamanashi Prefectural Museum of Art houses many fascinating works in addition to The Sower.

Let’s take a look at a few of the highlights from the museum’s collection.

Jean-François Millet

“Portrait of Pauline V. Ono” (c. 1841–1842)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

When Millet’s work was accepted into the Paris Salon for the first time in 1840, he left the capital and returned to his hometown of Cherbourg in Normandy, where he had once studied painting. There he met Pauline Virginie Ono, the daughter of a tailor. The two were soon married.

At that time, Millet had already established a solid reputation as a portrait painter in his hometown. His skill was so well recognized that even the former mayor of Cherbourg commissioned him for a portrait.

It was during this period that he painted Portrait of Pauline V. Ono. The contrast between light and shadow is striking, yet Pauline’s soft gaze and delicate expression give the work a gentle and calm atmosphere. Her slightly melancholic face and slender figure convey a quiet sense of innocence, as if revealing her inner emotions.

The following year, Millet took Pauline with him back to Paris. Sadly, she struggled to adjust to life in the bustling city. Her fragile health declined, and she passed away from tuberculosis in 1844 at a young age.

Jean-François Millet

“The Sleeping Seamstress” (c.1844–1845)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

After losing his first wife, Pauline, Millet returned to his hometown of Cherbourg filled with grief. There, he met Catherine Lemaire, who would later become his second wife.

Because Pauline had passed away only recently, many people around Millet strongly opposed the new relationship. Even so, he chose to leave for Paris with Catherine, beginning a new life together — almost like an elopement.

At that time, Millet had no steady income other than selling his paintings. To make a living, he created many works for the Paris Salon, including nudes and portraits of elegant, charming women. The Sleeping Seamstress was one of these works, and it is believed that Catherine herself posed as the model.

Though painted in dark, muted tones, the woman’s peaceful face and the hand gently slipping from her lap evoke a sense of calm and quiet everyday life. It feels like a tender moment from ordinary days — captured with warmth and empathy.

Millet and Catherine were officially married in 1853, and together they had nine children.

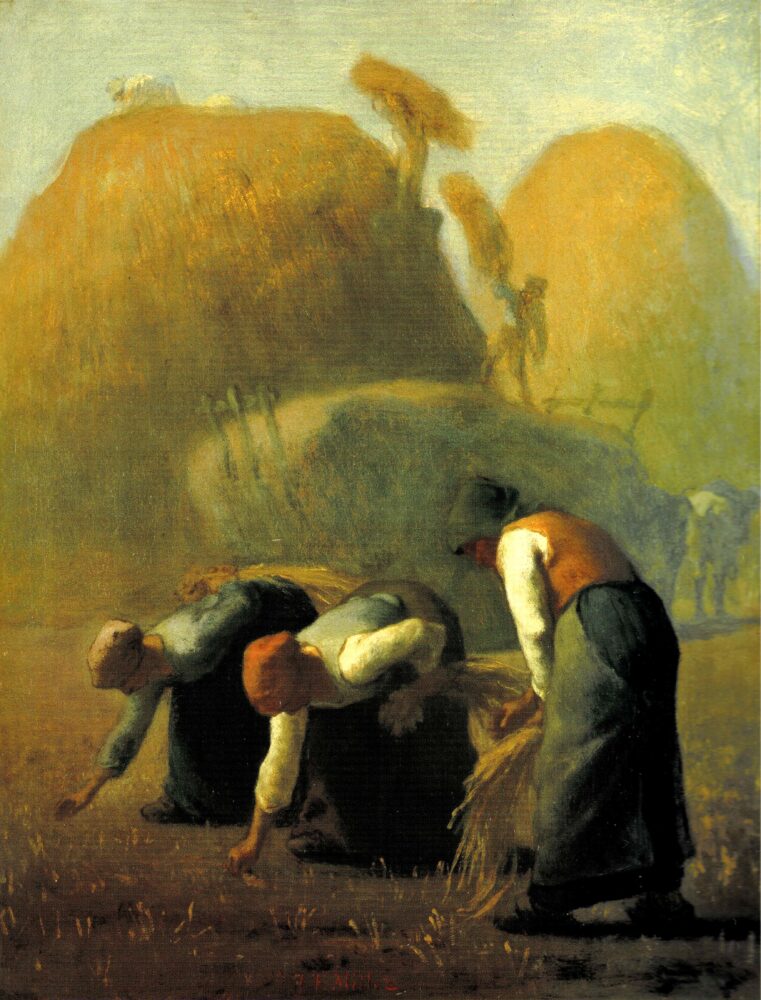

Jean-François Millet

“Summer, The Gleaners” (1853)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

When people think of Jean-François Millet, many immediately picture his famous masterpiece The Gleaners (1857, Musée d’Orsay). But before that painting, Millet had already explored the same theme in Summer, The Gleaners, considered the “prototype” of his later work.

This painting was part of a series representing the four seasons, commissioned by Paris real estate agent Alfred Feidou. Millet chose to depict not the lively harvest itself, but the quiet scene that follows — women collecting leftover wheat in the fields after the harvest.

Gleaning was a long-standing rural custom that allowed poor villagers and widows to gather what was left after the harvest. For many, it was an essential way to survive. Behind the image of a rich harvest, Millet reminds us of the social gap and the harsh reality of life for the poor.

Although Millet was born into a farming family, the practice of gleaning did not exist in his native Normandy. When he first saw this tradition, he was deeply moved — an experience that inspired him to create this poignant painting.

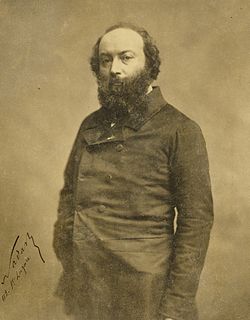

Théodore Rousseau

“Edge of the Forest, near the Gorges d’Apremont” (1866)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Théodore Rousseau was one of the leading figures of the Barbizon School, often mentioned alongside Jean-François Millet as one of the group’s “Seven Stars.” He was deeply admired for his poetic and dramatic approach to landscape painting.

While his works are realistic, they also carry a theatrical quality — as if a spotlight were cast on nature itself. His use of light creates a mysterious, almost spiritual atmosphere, turning ordinary forest scenes into deeply emotional landscapes.

In Edge of the Forest, near the Gorges d’Apremont, sunlight breaks through the clouds, illuminating parts of the forest with a sacred glow. Unlike the later Impressionists, Rousseau did not paint directly outdoors. Instead, he made sketches in nature and carefully refined them in his studio, striving to express his inner ideal through the natural world.

The Forest of Fontainebleau, located about 60 km southeast of Paris, was a beloved painting site for the Barbizon artists. When deforestation plans threatened the area in the mid-19th century, Rousseau became a central figure in the protest movement. For him, nature was not just scenery — it was something sacred, worthy of protection. The solemn and spiritual atmosphere of this work beautifully reflects his deep respect and love for the natural world.

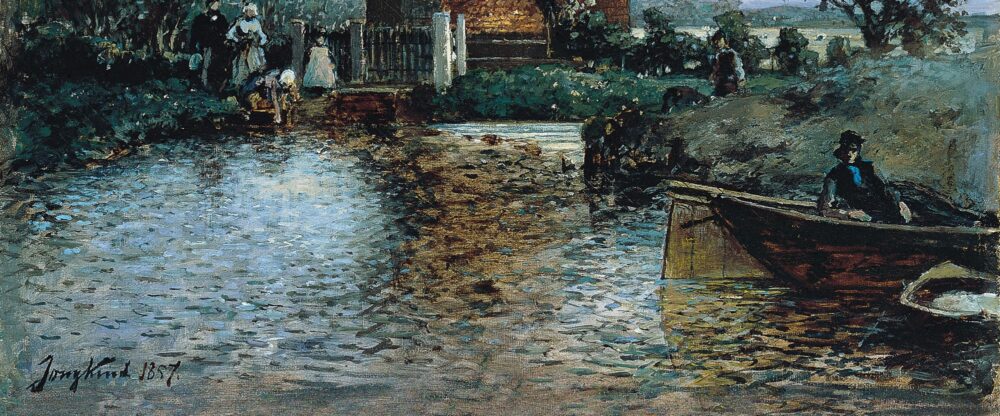

Johan Jongkind

“Moonlight at Dordrecht” (1872)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Johan Jongkind (1819–1891) was a Dutch painter celebrated for his poetic landscapes and his influence on the birth of Impressionism. Long before the Impressionists appeared, Jongkind was already experimenting with a key technique later known as divided brushstroke—placing colors side by side instead of mixing them on the palette.

You can already see this approach in his earlier work Windmills near Delft (1857), where light reflections on the water are painted with short, distinct strokes. By the time he created Moonlight at Dordrecht, this divided brushstroke technique became even clearer. The rippling surface of the water is filled with subtle color variations, capturing the flickering light of the moon with an Impressionist touch.

But Jongkind’s charm goes beyond technique. His use of light has a quiet poetry that feels almost spiritual. Especially in his evening and moonlit scenes, he conveyed the mysterious beauty of nature that transcends realism. In Moonlight at Dordrecht, the soft glow of the moon breaks through the clouds, bathing the Dutch town in a calm, dreamlike atmosphere.

Yamanashi Prefectural Museum of Art – Visitor Information

Location: 1-4-27 Kugawa, Kofu City, Yamanashi Prefecture

References

- Yojiro Ide, “The Truth About Millet, the ‘Painter of Peasants’”, NHK Publishing, 2014.

Comments