A Collection of Over 30,000 Works!

Located in Hachioji, Tokyo, the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum (TFAM) opened in 1983, founded by Daisaku Ikeda, president of Soka Gakkai International (SGI).

Guided by its motto, “Art speaks to the world,” the museum promotes international cultural exchange through a diverse range of artworks from Japan and abroad.

What makes this museum so impressive is both the quantity and quality of its collection.

TFAM’s holdings include Western paintings from the 16th century to contemporary art, as well as Japanese paintings, sculptures, and ceramics—more than 30,000 works in total.

The permanent exhibition features around 100 carefully selected pieces, rotated regularly to offer visitors a fresh experience each time.

One of the Few Museums in Japan with a Work by Georges de La Tour

Among its highlights is “Smoker” by Georges de La Tour, a masterpiece rarely seen outside Europe.

Only about 40 authentic works by La Tour exist in the world, and in Japan, they can only be found at Tokyo Fuji Art Museum and the National Museum of Western Art.

It’s so rare that visiting just to see this painting is worth the trip.

Though the museum is located a bit away from central Tokyo, it’s absolutely worth the visit.

If you love Western art, make sure to add this museum to your Tokyo itinerary!

Highlights from the Collection

The Tokyo Fuji Art Museum houses Western paintings from many different eras.

Here are some carefully selected masterpieces, introduced in chronological order.

Note: Works on display may change periodically. Not all of the pieces introduced here are always exhibited.

Before your visit, please check the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum website.

17th Century Works

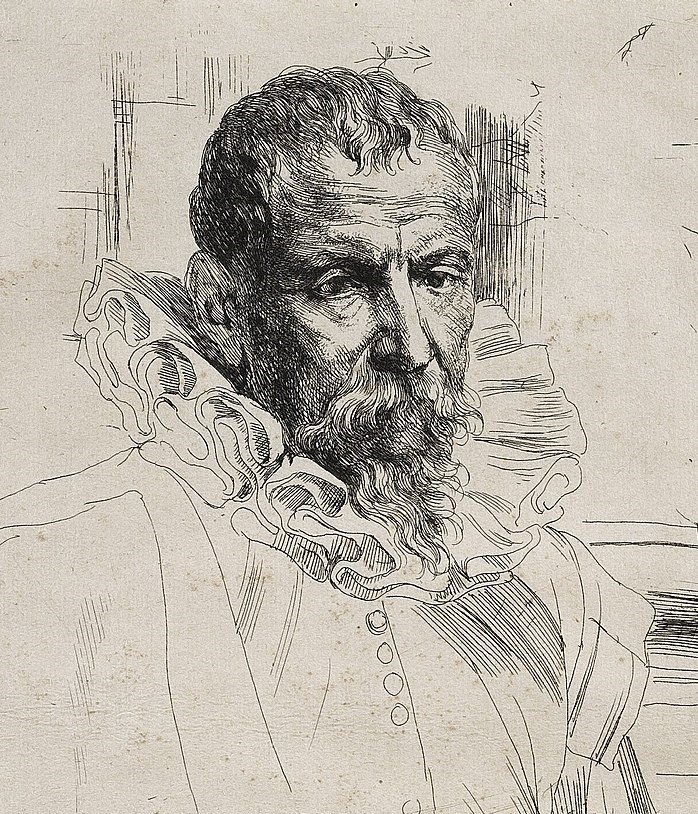

Pieter Brueghel the Younger

“Peasant Wedding Feast” (1630)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1564–1636) was a Flemish painter active in the 17th century and the eldest son of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, the famous “painter of peasants.”

While he followed his father’s style, he developed a more colorful and detailed approach to rural life.

This version of “Peasant Wedding Feast”, owned by the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, is a reinterpretation of his father’s 1567 original, now housed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

Such works were not simple copies; they often included new arrangements and brighter colors, reflecting both the strong demand for Bruegel’s themes and the workshop-based art production of the time.

The painting captures a lively village wedding scene: wooden tables lined with bowls, peasants carrying food, and guests chatting on benches.

Every detail is finely rendered, offering a vivid glimpse into peasant life in late 16th- to early 17th-century Flanders.

Though the subject is humble daily life, Brueghel’s keen eye for composition, rhythm, and color makes the work stand out as a true masterpiece.

It remains an important example of how the Brueghel family’s artistic legacy was passed down through generations.

— Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Georges de La Tour

“Smoker” (1646)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Georges de La Tour (1593–1652) was a 17th-century French painter known for his serene, candlelit scenes.

No one captured the quiet beauty of light and shadow quite like him. From religious subjects to scenes of everyday life, La Tour drew viewers into a mysterious world of stillness and glow.

Surprisingly, La Tour’s genius went unrecognized for centuries. His works were rediscovered only in the 20th century.

“Smoker”, owned by the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, was found in 1973 and later acquired by the museum at an auction in 1985.

Bearing the artist’s signature, this piece is considered one of the finest authentic versions among several similar compositions.

The painting depicts a man lighting his pipe in the darkness. Tobacco, newly introduced from the Americas in the 16th century, was then believed to have medicinal properties and quickly became popular.

In this way, the painting reflects the culture of its time while also conveying the gentle warmth of a small flame in the stillness of night.

The soft glow illuminating the man’s face captures a fleeting, intimate moment — calm yet deeply human.

La Tour’s ability to find drama in silence is what makes his art timeless. Don’t miss the chance to see this masterpiece up close at the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum.

18th Century Works

François Boucher

“Pastoral Music” (1743)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Wrapped in soft pastel colors, this enchanting painting by François Boucher feels like stepping into a dream.

Set in a peaceful forest with sheep grazing nearby, a young shepherd plays the flute while a woman gazes at him with affection.

The gentle, romantic mood fills the entire scene. Yet, this is not a real countryside — it is the idealized rural world imagined by the 18th-century French aristocracy.

Boucher was a leading painter of the Rococo period, celebrated for his delicate brushwork and silk-like tones.

He skillfully transformed themes of love and beauty into elegant, decorative art.

“Pastoral Music” perfectly reflects this style, almost like a scene from a graceful ballet.

In Boucher’s world, there is no trace of labor or hardship — only whispers of love and harmony with nature.

His idyllic vision invites viewers to momentarily escape everyday life and lose themselves in gentle fantasy.

It’s a perfect example of Rococo art — a painting to enjoy when you want to dream a little within reality.

Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal)

“Piazza San Marco, Venice” (c.1732-1733)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Looking at this painting feels like time-traveling to 18th-century Venice.

Created by Canaletto, this view of Piazza San Marco captures one of the most iconic landmarks of the city — just as vibrant then as it is today.

In the composition, the Basilica di San Marco appears on the left, the 100-meter-high bell tower rises in the center, and the Procuratie Nuove stretches across the front.

Amazingly, you can still enjoy almost the same view when visiting Venice today — try comparing it with this masterpiece when you stand in the square!

One of the highlights of this work is Canaletto’s masterful use of light.

The bright Venetian sky is painted with soft gradation, while sunlight streaming from the west casts crisp, dramatic shadows across the plaza.

This balance of light and shade gives the entire scene a cinematic, three-dimensional feel.

Look closely, and you’ll notice the astonishing precision in every detail — from the carvings on the basilica to each individual window.

Canaletto’s skill in perspective and realism made his cityscapes extremely popular among travelers, especially British aristocrats visiting Venice during the Grand Tour.

This painting is believed to have been created as one of those treasured “souvenirs” of the journey.

Standing before this work, you may find yourself longing to travel again — to wander through Venice’s sunlit plazas and quiet canals, just as people did centuries ago.

19th Century Works

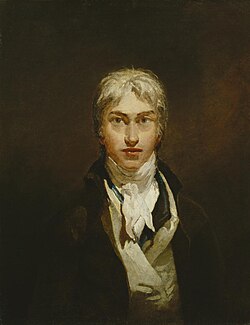

William Turner

“Helvoetsluys; the City of Utrecht, 64, Going to Sea” (1832)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A beam of sunlight breaks through the clouds, illuminating the sea and sky.

A majestic ship glides across the waves — a scene painted almost entirely with light and air.

This is “Helvoetsluys; the City of Utrecht, 64, Going to Sea” (1832), by the British master William Turner.

While it doesn’t yet show the dissolving, atmospheric style of his later years, you can already feel Turner’s genius in the way he captures reflected light and the density of the sea with bold, textured brushstrokes.

The painting conveys both the power and mystery of nature — themes that would define his entire career.

This work also comes with a fascinating story.

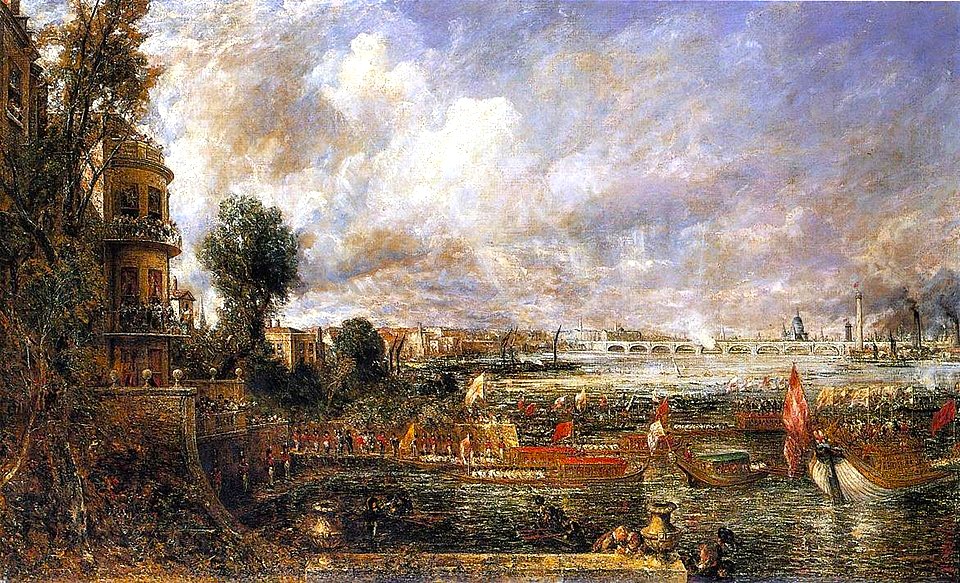

When it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1832, it hung right next to The Opening of Waterloo Bridge by Turner’s rival, John Constable.

Constable’s piece was large and vividly colored — stealing much of the attention in the gallery.

So, what did Turner do?

He quietly walked up to his own canvas and added a single red buoy to the calm sea.

That small stroke instantly transformed the composition — creating a strong focal point amid the light and mist.

Constable, half-amused and half-stunned, reportedly said:

“He has been here and fired a gun!”

That legendary moment has since become one of the most famous rivalries in art history.

When you stand before this painting, imagine that dramatic scene — two masters pushing each other to greatness in the golden age of British landscape art.

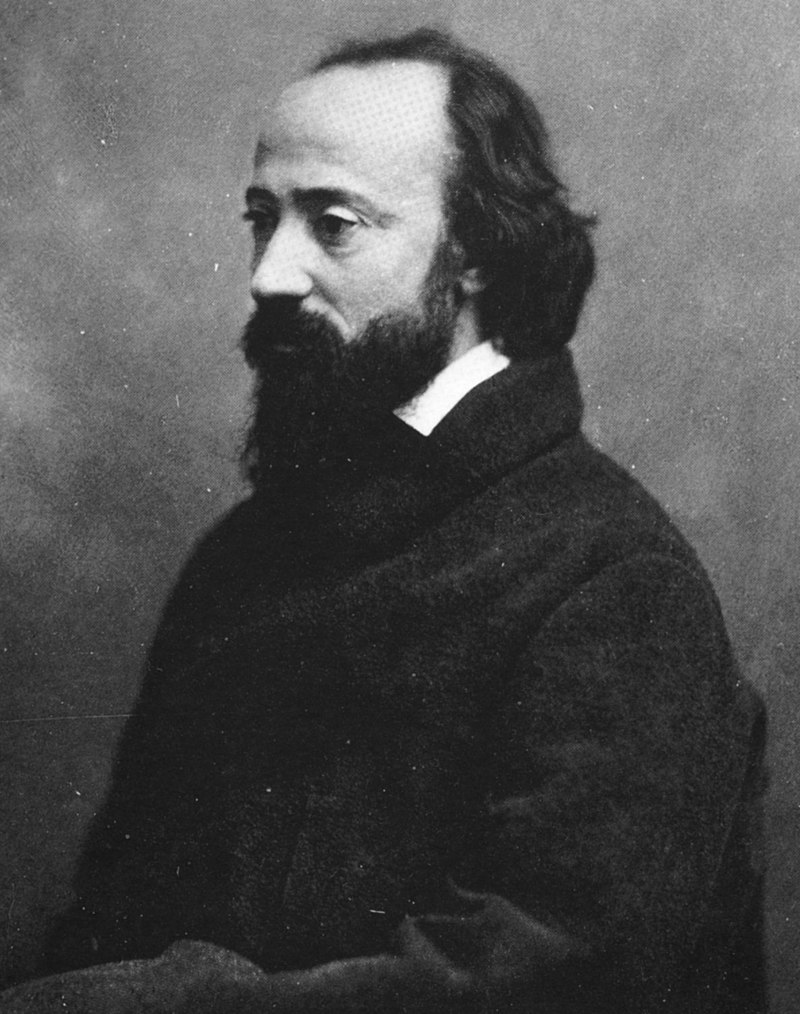

Charles-François Daubigny

“Seaside of Villerville” (1870)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Charles-François Daubigny was one of the leading landscape painters of 19th-century France and a key member of the Barbizon School. His practice of painting outdoors greatly influenced the later Impressionist artists. In 1868, he even served as a juror for the Paris Salon, where he supported and praised the innovative techniques of the emerging Impressionists.

Daubigny had a deep love for rivers and the sea. He converted his own boat into a floating studio, traveling along the waterways to paint directly from nature. “Seaside of Villerville” beautifully reflects that affection for the water.

The painting depicts the coast of Normandy in northwestern France. In the distance, you can see the wide estuary of the Seine River flowing into the English Channel. In the foreground, women gather shellfish on the tidal flats, creating a peaceful, lifelike scene where you can almost feel the salty sea breeze.

Interestingly, Daubigny painted this work in 1870—the same year the Franco-Prussian War broke out. To escape the turmoil, he left Paris and stayed in Villerville and later in London. Yet, this painting feels calm and serene, untouched by war. It reminds us that even during turbulent times, the quiet rhythms of everyday life continue.

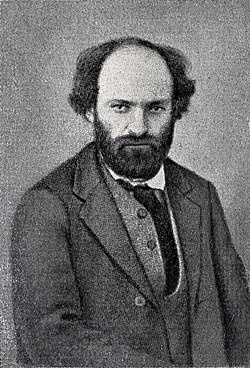

Paul Cézanne

“Detour in Auvers” (c.1873)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Known as the “father of modern painting,” Paul Cézanne also went through a long period of experimentation. In his early years, he was influenced by Eugène Delacroix and Gustave Courbet, creating works with dark tones and heavy brushstrokes. But around 1872, after moving to the quiet village of Auvers-sur-Oise northwest of Paris, his style began to change dramatically.

A key turning point came from his friendship with Camille Pissarro, who lived nearby in Pontoise. The two artists often painted outdoors together, and under Pissarro’s influence, Cézanne’s colors became brighter and his touch softer.

“Detour in Auvers” was created right in the midst of this transformation. The gentle sky, curving road, and simple houses are bathed in warm light, giving the work an open and peaceful feeling—very different from the darker tone of his earlier works.

If you look closely, you can see Cézanne’s signature diagonal brushstrokes in the grass and soil, an early sign of the “constructive brushwork” that would later define his mature style. The rooftops and walls already have a subtle geometric quality, hinting at his growing interest in simplifying nature’s forms—a direction that would eventually inspire Cubism.

Painted around the same time, “The Hanged Man’s House” shares similar traits. Perhaps Cézanne found in these rustic country houses the first “shapes” that would lead him toward a new way of seeing art.

A quiet village road, yet within it lies the seed of modern art’s great transformation.

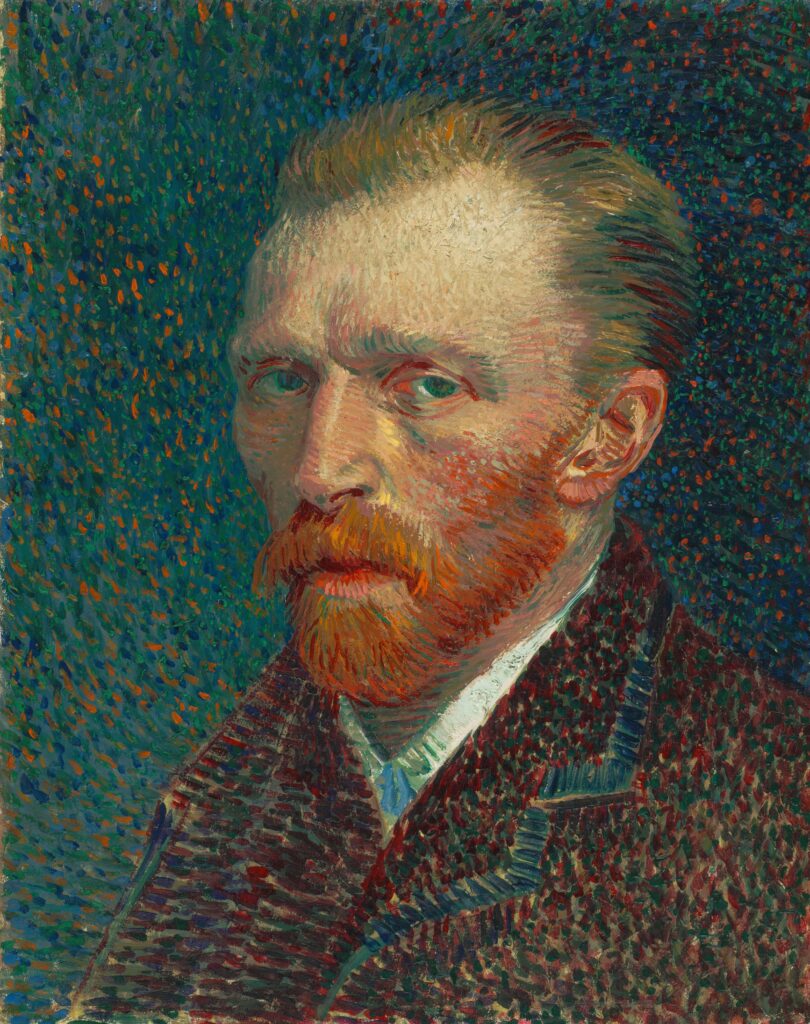

Vincent van Gogh

“Cottage with Peasant Woman Digging” (1885)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Although Vincent van Gogh is best known as a “painter of color,” his early works—especially those painted in his homeland, the Netherlands—were surprisingly dark and subdued.

This painting, “Cottage with Peasant Woman Digging”, in the collection of the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, belongs to that early period. It was created while Van Gogh was living in the small Dutch village of Nuenen and shows a peasant woman at work in the field, rendered in quiet, earthy tones.

Before becoming a painter, Van Gogh once aspired to be a preacher, and he deeply sympathized with the lives of poor farmers and laborers. In these early years, he tried to depict them “as they truly were,” without idealization.

However, these somber, heavy-toned works were hard for his younger brother Theo—who worked as an art dealer—to appreciate or sell. Even The Potato Eaters, considered the culmination of his Dutch period, was never exhibited and hung only on Theo’s apartment wall.

During his time in Nuenen, Van Gogh also became entangled in a local scandal involving a woman, which led him to leave the village—and he would never return to the Netherlands again.

Yet that departure marked the beginning of a new chapter. Through his journeys to Antwerp, Paris, and finally Arles, Van Gogh gradually transformed his palette, discovering the radiant colors and expressive brushwork we know so well today.

20th Century Works

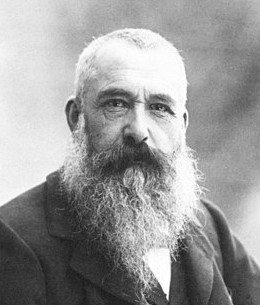

Claude Monet

“Water Lilies” (1908)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Claude Monet devoted his life to capturing the ever-changing effects of light. He painted the same subjects repeatedly—haystacks, poplar trees, and the Rouen Cathedral—to study how light transformed them at different times of day and in different weather conditions. Each series became a visual dialogue between nature and light.

Among these, Water Lilies stands as the crowning achievement of his late career and one of the most iconic subjects in modern art. Today, many versions of Water Lilies can be found in museums across Japan, beloved for their serene and timeless beauty.

This 1908 painting from the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum belongs to the second series of Water Lilies. Monet focused on the water’s surface, depicting both the floating blossoms and the reflections of light and surrounding trees. The large canvas, over one meter tall, immerses viewers in a tranquil world where water and air seem to merge into one.

In this still, meditative space, a few delicate pink lilies bloom quietly—small yet powerful symbols of life and renewal within nature’s calm embrace.

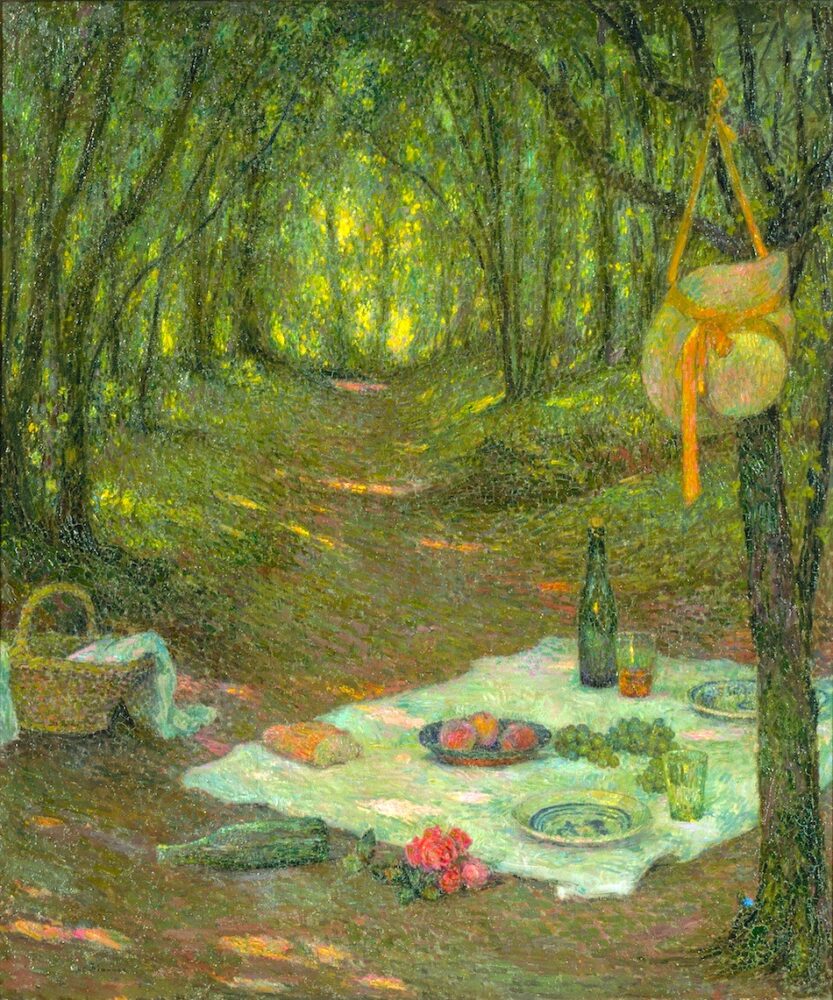

Henri Le Sidaner

“A Break in the Woods, Gerberoy” (1925)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Soft sunlight filters through the trees, illuminating a quiet clearing in the woods. On a white tablecloth, fruit, bread, and wine are gently arranged—as if someone has just paused here for a peaceful rest, or perhaps is about to arrive.

This poetic scene was painted by the French artist Henri Le Sidaner, whose style bridges Impressionism and Symbolism. While influenced by Monet and other Impressionists, Le Sidaner sought to capture not just light, but also emotion, memory, and stillness.

In “A Break in the Woods, Gerberoy”, the composition draws the viewer’s gaze into the depth of the forest, where everything is bathed in soft green light. Although no people appear in the painting, a quiet human presence seems to linger, as if time itself has paused.

Le Sidaner created this work in the beloved village of Gerberoy, where he spent much of his life. His art celebrates the beauty of simple moments and the harmony between nature and everyday life.

It’s a painting that makes you want to step inside, take a deep breath, and rest for a while in its gentle calm.

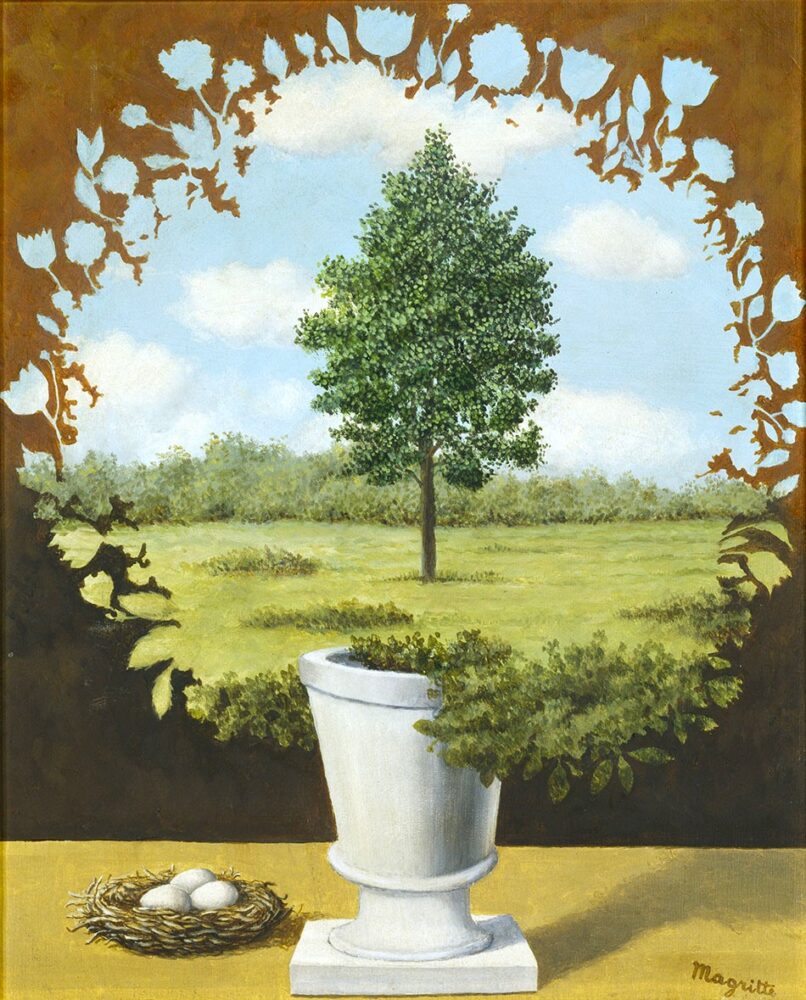

René Magritte

“The Resumption” (1965)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

René Magritte (1898–1967) was a Belgian Surrealist painter known for creating mysterious and thought-provoking images that challenge our sense of reality.

In “The Resumption”, one of his late works, the silhouette of a vase filled with flowers is cut out to reveal a landscape beyond—a grassy field stretching into the distance. This technique, called dépaysement, combines familiar objects in unexpected ways to produce a dreamlike and unsettling effect. It became one of the signature methods of Surrealism.

Before becoming a full-time painter, Magritte worked in graphic design and advertising, and that experience shaped his clean, striking compositions. In this painting, the precise outline of the vase and the central tree framed within it give the work a refined, almost Pop Art–like sense of design.

Everyday objects are reimagined here, urging us to question what we see—and reminding us that the boundary between reality and illusion is thinner than we think.

Tokyo Fuji Art Museum – Visitor Information

Location: 492-1 Yanomachi, Hachioji, Tokyo Prefecture

Comments