What Are Water Lilies, Anyway?

When you think of the Impressionist master Claude Monet, you probably think of Water Lilies.

He painted the pond in his own garden over and over—more than 250 paintings in total. This is a series he carefully built over 30 years, a true labor of love.

The most famous work is the “Grand Décoration” at the Orangerie Museum in Paris.

It’s massive—2 meters high and 91 meters long—and it feels like stepping right into Monet’s world. This is one of his late masterpieces, a true culmination of his life’s work.

Definitely something to experience in person someday.

img: by Jason7825

Monet and Japan: An Unexpected Connection

Have you noticed that Japanese people really love Monet?

Exhibitions always have huge lines. So, why is he so popular?

The truth is, Monet himself was influenced by Japanese culture.

He decorated his dining room with Ukiyo-e prints and even added Japanese garden elements to his garden.

Maybe when Japanese people say, “I love Monet’s Water Lilies,” it’s partly because the paintings resonate with a Japanese sense of beauty.

img: by Globetrotteur17… Ici, là-bas ou ailleurs…

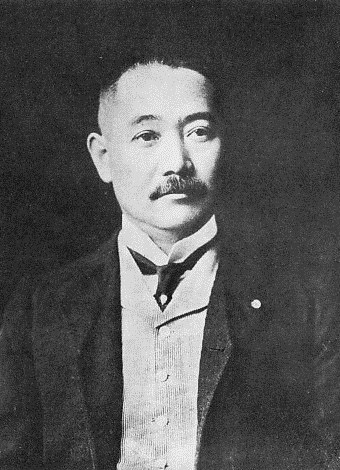

Here’s another interesting story: Monet never sold his “Grand Décoration” series during his lifetime. But one person did manage to acquire a part of it—Kojiro Matsukata, the businessman who later built the collection of today’s National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo.

We cover the story behind this in the article, so be sure to check it out!

See Water Lilies All Across Japan: Museums That Have Monet’s Works

Many people think, “I have to go to Paris to see Water Lilies,” but in fact, you can see many of Monet’s Water Lilies at museums throughout Japan. For example:

- Hakone, Pola Museum of Art – The first series, Water Lilies Pond

- Kagoshima City Museum of Art – Early, fresh Water Lilies

- Tokyo, National Museum of Western Art – A piece believed to be part of the Orangerie “Grand Décoration” series

You might be surprised how many Water Lilies you can see in Japan. Why not make it a fun challenge—a Water Lilies tour across Japan?

Next, let’s take a look at all the Water Lilies you can see at museums across Japan.

Water Lilies in the “Tohoku Region”

Yamagata Prefecture

Yamagata Museum of Art

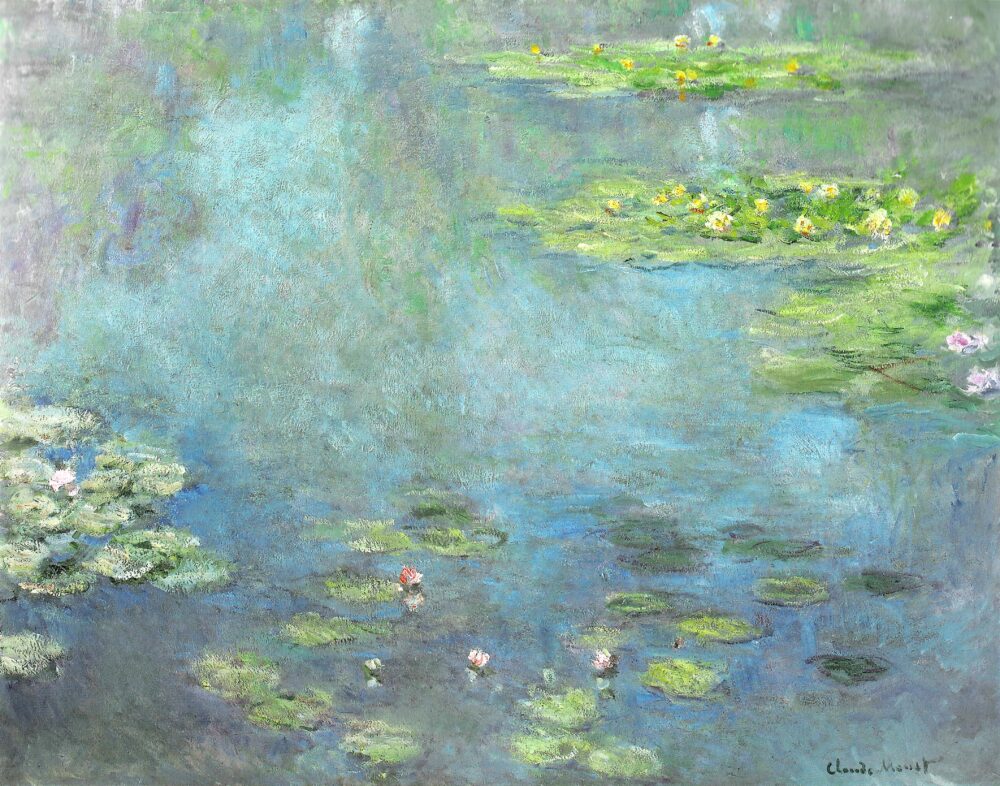

” Water Lilies ” (1906)

Oil on canvas, 81.0 × 92.0 cm

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

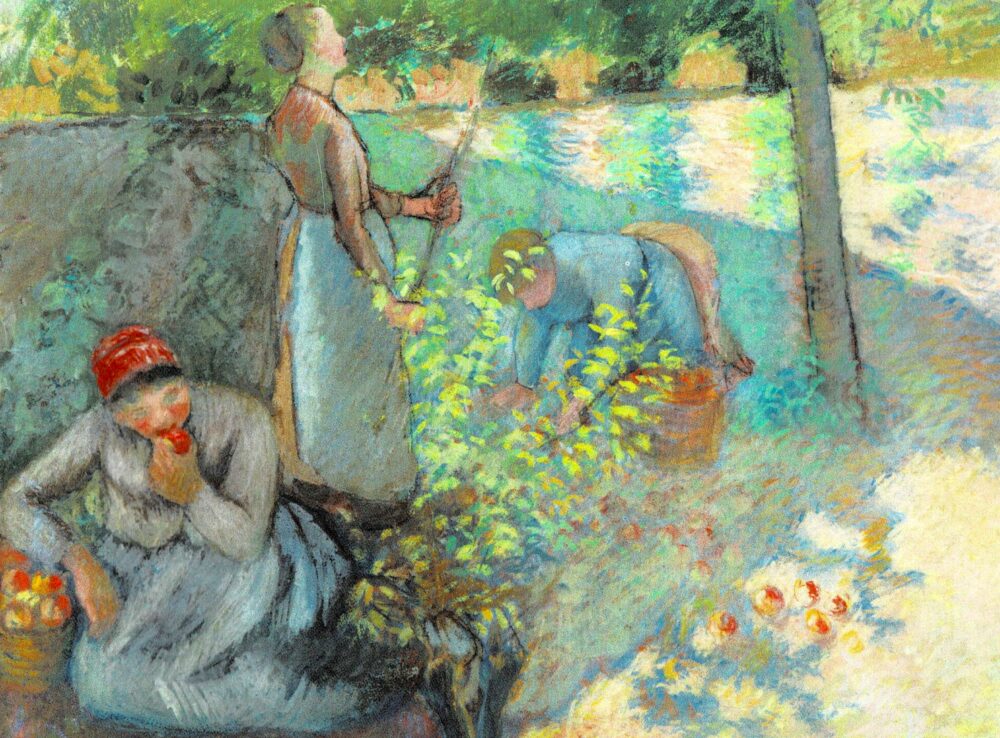

Monet painted an enormous number of Water Lilies, which can be roughly grouped into three series:

Early Series (1897–1900)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Second Series (1903–1908) – More Transparent Colors

Israel Museum

Late Series “Grand Décoration” (1914–1926)

Musée de l’Orangerie

The 1906 Water Lilies at Yamagata Museum of Art belongs to the Second Series.

During this period, Monet began painting not only the lilies in the pond but also the reflections of sky and clouds on the water surface. The background trees gradually disappear, showing how Monet’s attention increasingly focused on the water itself.

This particular painting is unique. The arrangement of the lilies creates depth, giving a different impression from the flatter “Grand Décoration” works that came later. Look closely, and you can see reddish clouds reflected in the water—perhaps an evening scene. Some flowers are beginning to close, creating a sense of peaceful twilight.

The work beautifully captures the coolness of a clear pond and the warm evening colors, freezing a moment of nature’s subtle changes in a single painting.

Kanto Region

Gunma Prefecture

Museum of Modern Art, Gunma

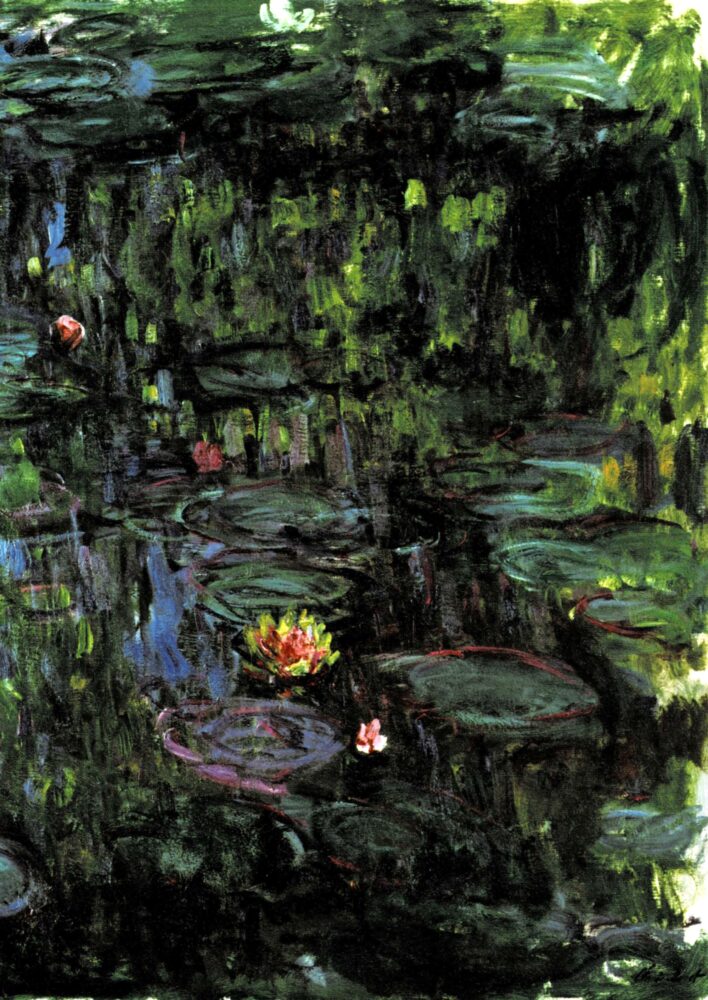

” Water Lilies ” (1914-1917)

Oil on canvas, 131.0 × 95.0 cm

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Here’s a surprising fact: Monet was barely appreciated immediately after his death.

After World War I, there was a trend of returning to order. People sought classical, stable paintings, and with modern art rising, Monet’s works were considered out of fashion, almost forgotten.

Monet’s home in Giverny also fell into disrepair. During the war, the roof was damaged by shells, left unrepaired, and some stored works were damaged. Some paintings even had damaged parts cut out during restoration.

The Museum of Modern Art, Gunma’s Water Lilies went through a similar fate—its top section is said to have been cut.

Yet, what comes through in the painting is strength and vitality. The lilies, painted in bright colors, stand out against the darker water, creating a clear, striking impression. Reflections of purple—perhaps wisteria flowers—add beautiful accents across the pond.

Painted around 1914–1917, this piece comes from the time when Monet started seriously working on the “Grand Décoration” series. He began using larger canvases and produced more powerful, immersive works. This painting is a glimpse into that period of his life.

Chiba Prefecture

Former Kawamura Memorial DIC Museum of Art

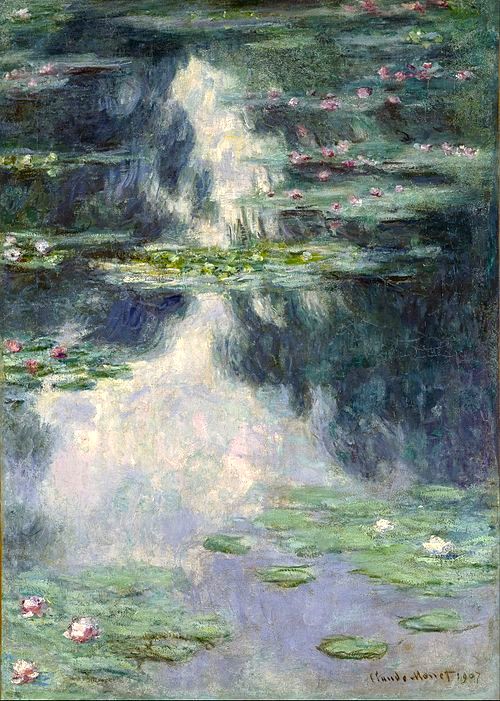

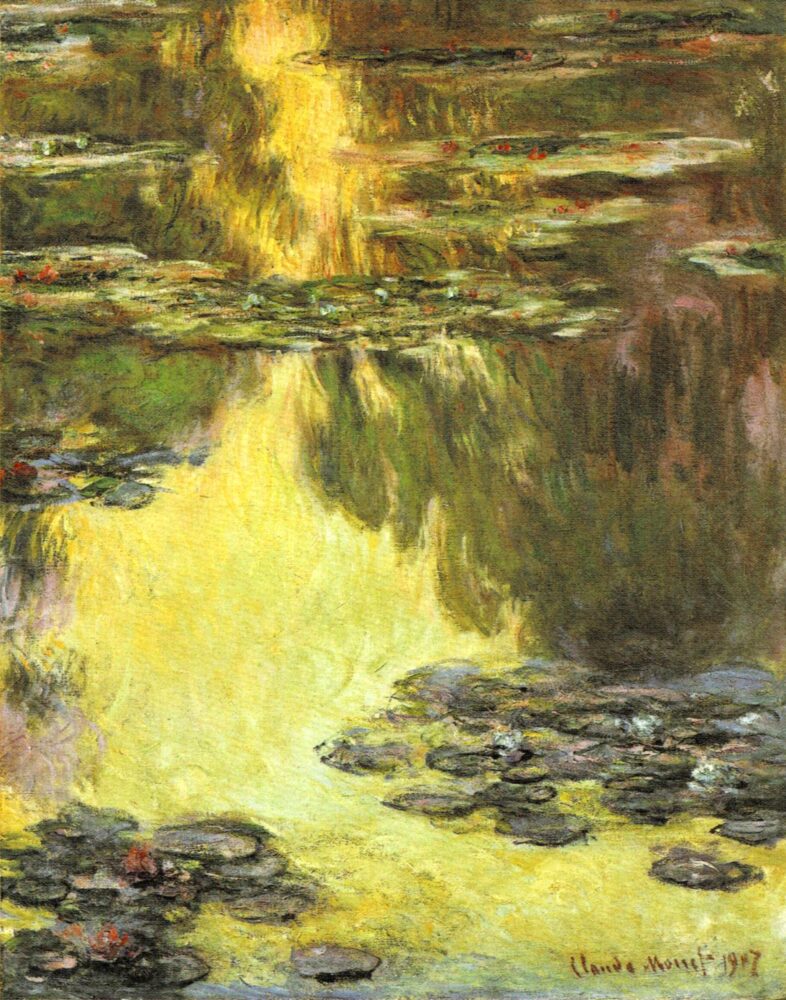

” Water Lilies ” (1907)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

This Water Lilies painting, once part of the collection at the former Kawamura Memorial DIC Museum of Art in Chiba, belongs to Monet’s Second Series—a period when he focused intensely on the water surface itself.

What makes this painting especially interesting is the reflected colors of the trees and sky. A warm, yellow glow—suggesting sunset—spreads across the surface, creating an upside-down world. The more you look, the more the entire painting starts to feel as if it has been flipped.

In fact, the French critic Louis Gillet described this work as “a painting turned upside down.” Viewers can’t quite tell whether they are looking at the pond or at the reflected scenery, and that gentle confusion creates a floating, dreamlike sensation. Gillet called this effect an early form of “abstraction.”

However, Monet himself had no intention of creating abstract art. He was committed to painting exactly what he saw. So while the work may look abstract, it is, for Monet, a faithful record of light and time.

This piece captures the enchanting glow of sunset on a quiet pond—an atmospheric moment preserved on canvas.

Tokyo Prefecture

The National Museum of Western Art

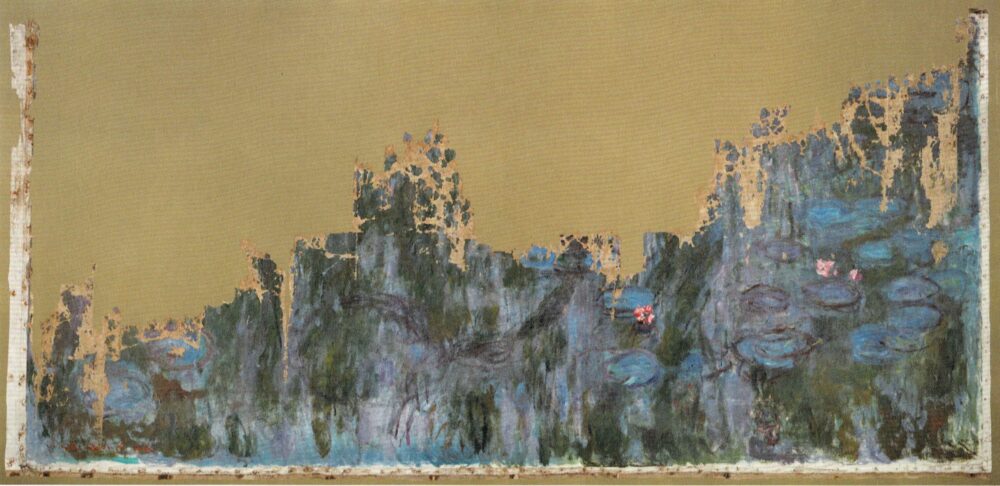

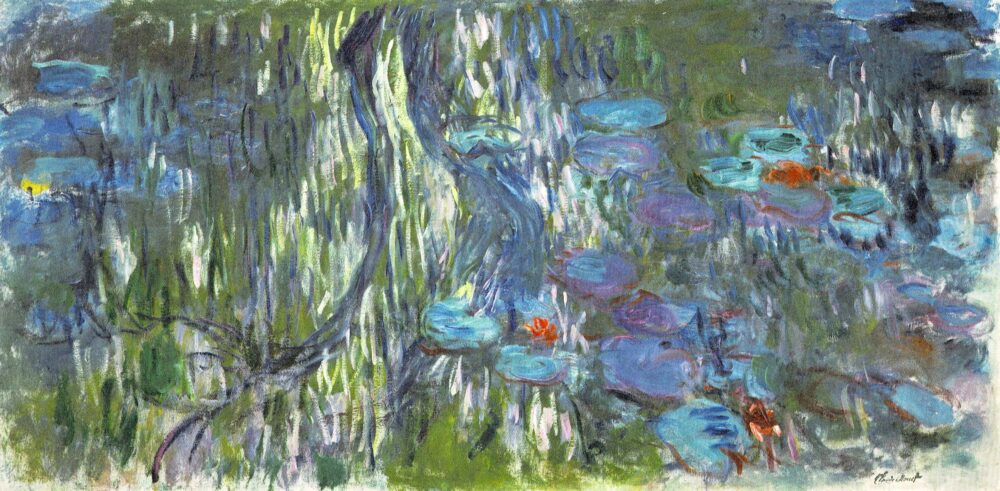

” Water Lilies, Reflections of Weeping Willows ” (1916)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

The National Museum of Western Art is famous for the Matsukata Collection, assembled by Japanese businessman Kōjirō Matsukata before World War II. Much of the collection, however, was lost due to financial crises, fires, war, and postwar confiscation. Many pieces never made it back to Japan.

This Water Lilies, Reflections of Weeping Willows is one of those works with a dramatic history.

Matsukata bought it directly from Monet, then stored it at the Rodin Museum in Paris. During the war, it was evacuated to a private home—but eventually forgotten and considered lost.

In 2016, the painting was miraculously rediscovered in France, and finally returned to Japan.

Sadly, the upper portion had been damaged during its long evacuation. Even so, the work is enormously significant: it is the only piece of Monet’s “Grand Décoration” that he sold during his lifetime.

Why did Monet sell this monumental work to Matsukata?

The answer lies in Monet’s tense relationship with the French government. He had planned to donate the “Grand Décoration” series to the nation, but he was deeply dissatisfied with the proposed exhibition spaces. His frustration grew so intense that he nearly withdrew the donation entirely.

It was during this turbulent time that Matsukata appeared. The timing of their negotiations—and Monet’s irritation—likely played a major role in why this one part of the “Grand Décoration” ended up in Matsukata’s hands.

Monet was also a devoted admirer of Japanese culture. He collected ukiyo-e prints and even built a “Japanese-style bridge” over his water garden in Giverny. His affection for Japan may have contributed to this extraordinary transaction.

img: by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra

Before the Orangerie Museum was selected, one proposed exhibition site for the “Grand Décoration” was Hôtel Biron. After many twists and turns—driven largely by Monet’s insistence on perfect display conditions—the series eventually found its permanent home at the Orangerie.

” Water Lilies ” (1916), The National Museum of Western Art

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

About a year after acquiring Water Lilies, Reflections of Weeping Willows, Kōjirō Matsukata returned to negotiate with Monet once again.

This time, he did something astonishing: he handed Monet a check for 800,000 francs—equivalent to roughly 150 million yen today—and asked him to choose one painting. The deal was so extraordinary that it was even reported in the local newspapers.

For reference, Matsukata had previously purchased 15 works, including Reflections of Weeping Willows, for 1 million francs total. In other words, he now offered almost the same amount of money for a single painting. Incredible, isn’t it?

Naturally, Monet could not hand over an unremarkable piece. It is believed that he selected this monumental work—measuring over 200 cm on each side—from the group related to the Grand Décoration.

To Monet, Matsukata was more than a client; he was a trusted patron. This painting was chosen especially for him—truly a “premium” work.

If you visit the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo, you can feel its overwhelming scale for yourself. No photograph or measurement can capture the sheer presence of this masterpiece.

” Water Lilies ” (1897-1899), The National Museum of Western Art

Oil on canvas, 73.3 × 101 cm

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

This early Water Lilies painting was recently added to the public display at the National Museum of Western Art.

Interestingly, it predates even Monet’s First Series of Water Lilies.

At first glance, the composition might look similar to the later Second Series, which focuses heavily on the water surface. But look closely: during this period, Monet still treated the water lilies themselves as the main subject.

The carefully painted outlines of the flowers and the delicate shifts of color reflected on the water show a quiet, observant Monet—very different from the bold, almost abstract works of his later years.

It’s a rare chance to see the serene beginnings of a series that would eventually become one of the most iconic bodies of work in art history.

▶ Read more about The National Museum of Western Art here.

Artizon Museum

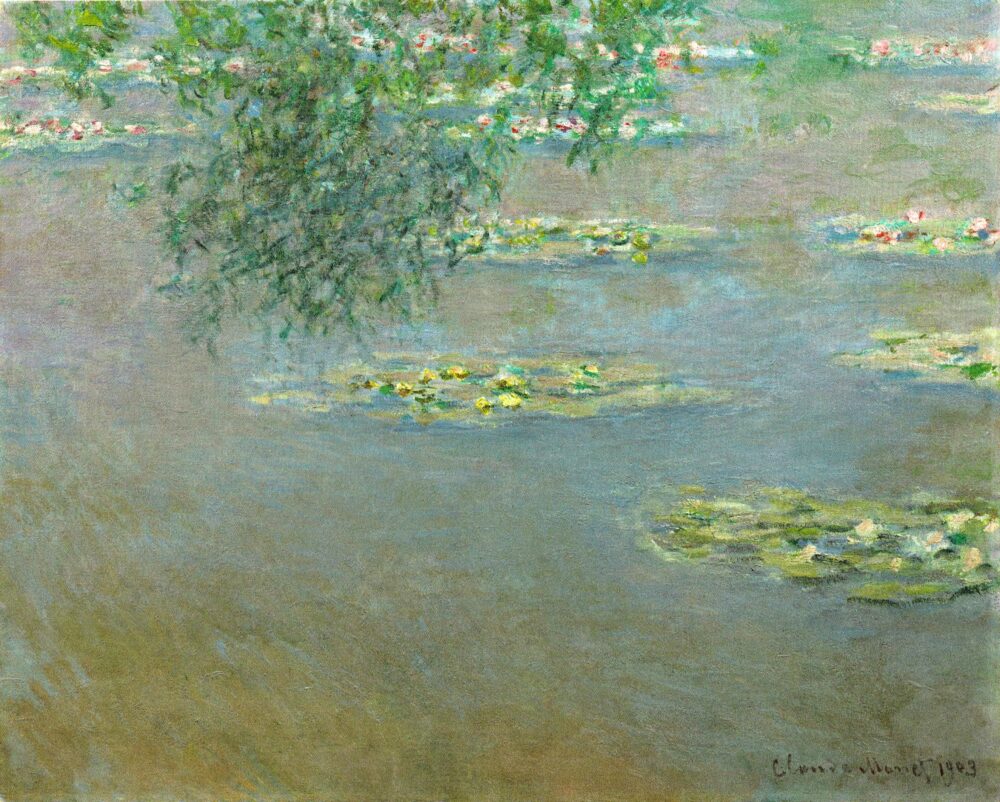

” Water Lilies ” (1903)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

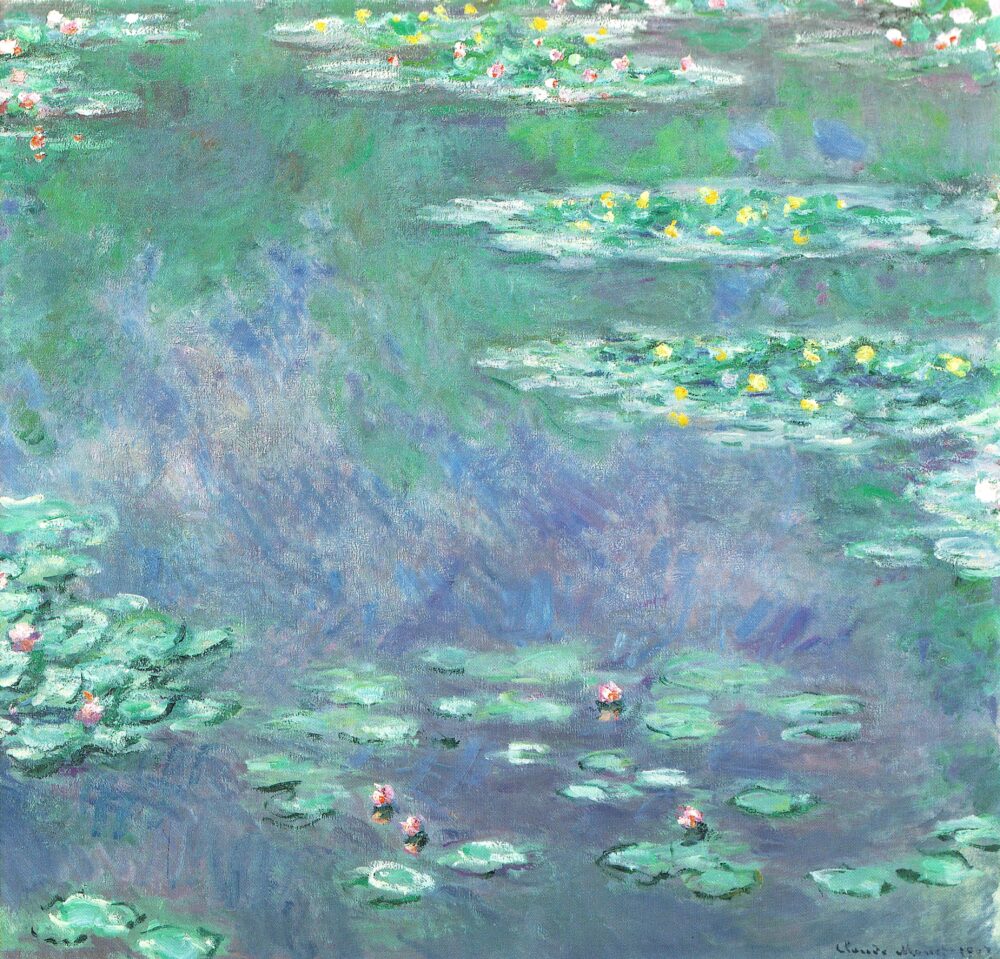

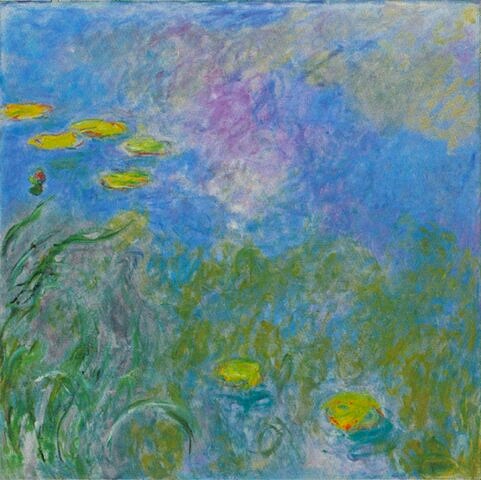

In 1901, Monet undertook major renovations to expand his “water garden,” enlarging the pond to nearly five times its original size. Once the newly redesigned garden settled in, he returned to painting Water Lilies in 1903 with renewed intensity.

From 1903 to around 1908, he created roughly 80 works, 48 of which were shown at the 1909 Paris exhibition Water Lilies: Series of Waterscapes. This group of paintings—later known as the “Second Series”—is now considered one of Monet’s most iconic achievements.

The Artizon Museum’s Water Lilies was painted early in this Second Series.

While Monet’s later works focus almost entirely on the surface of the water, this earlier canvas still includes elements like the drooping willow leaves in the foreground, letting us see the pond as part of a broader “landscape.”

img: by World3000

” Water Lilies ” (1907), Artizon Museum

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

This work belongs to Monet’s Second Series and was painted in 1907, the same year as the Water Lilies once held by the Kawamura Memorial DIC Museum of Art. The composition is almost identical, yet the overall impression is completely different. A slight shift in sunlight can transform the appearance of the pond—sometimes dramatically.

For Monet, this constant change in natural light was a major challenge.

The scene he observed just minutes earlier would already look different, making it nearly impossible to capture a single, consistent impression.

To solve this, Monet developed his “multiple canvas method.” He set up several canvases at once and switched between them as the light changed. In a way, it was like painting a “time-lapse of light,” all in real time.

This Water Lilies may have been one of the works created amid that lively back-and-forth.

It’s easy to imagine Monet quickly rotating canvases, trying to keep up with the shifting light—an image that feels almost endearing.

▶ Read more about the Artizon Museum here.

Tokyo Fuji Art Museum

” Water Lilies ” (1908)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

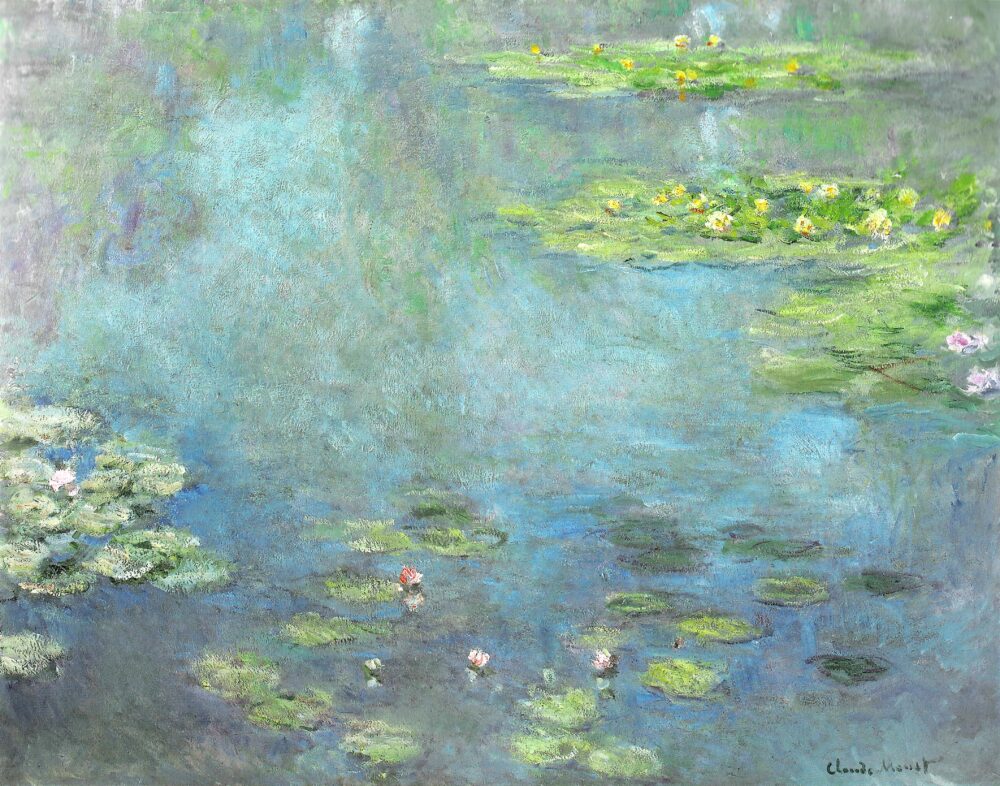

The 1909 exhibition Water Lilies: Series of Waterscapes at Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris was a major success.

But interestingly, the show was originally scheduled for 1907.

Just one month before the opening, Monet suddenly informed the gallery director that he had “destroyed 30 canvases” and requested to postpone the exhibition. The show didn’t open the following year either, and ultimately it was delayed by two years. For the gallery, which had already been preparing everything, this must have felt like a bolt from the blue.

Behind this last-minute cancellation was Monet’s relentless perfectionism. His wife Alice later recalled, “Monet pierced his canvases every day.” His determination was almost frightening, so the story of him destroying 30 works may not be much of an exaggeration after all.

This Water Lilies was painted during that intense period.

Yet the atmosphere we feel from the painting is surprisingly calm. The water surface is gently illuminated, with almost no sharp contrasts, and the entire scene is rendered in soft, pastel-like tones.

Even when the creative process was like a storm, the finished work radiates tranquility and harmony.

This painting captures that very “paradoxical charm” that is so typical of Monet.

▶ Read more about the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum here.

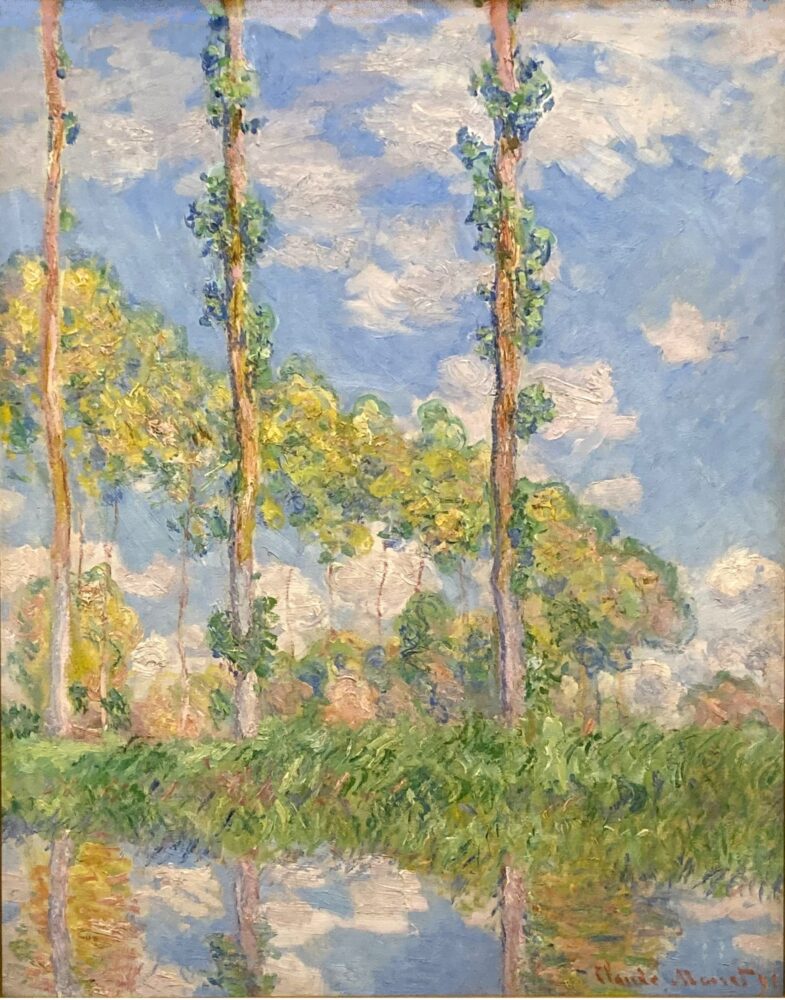

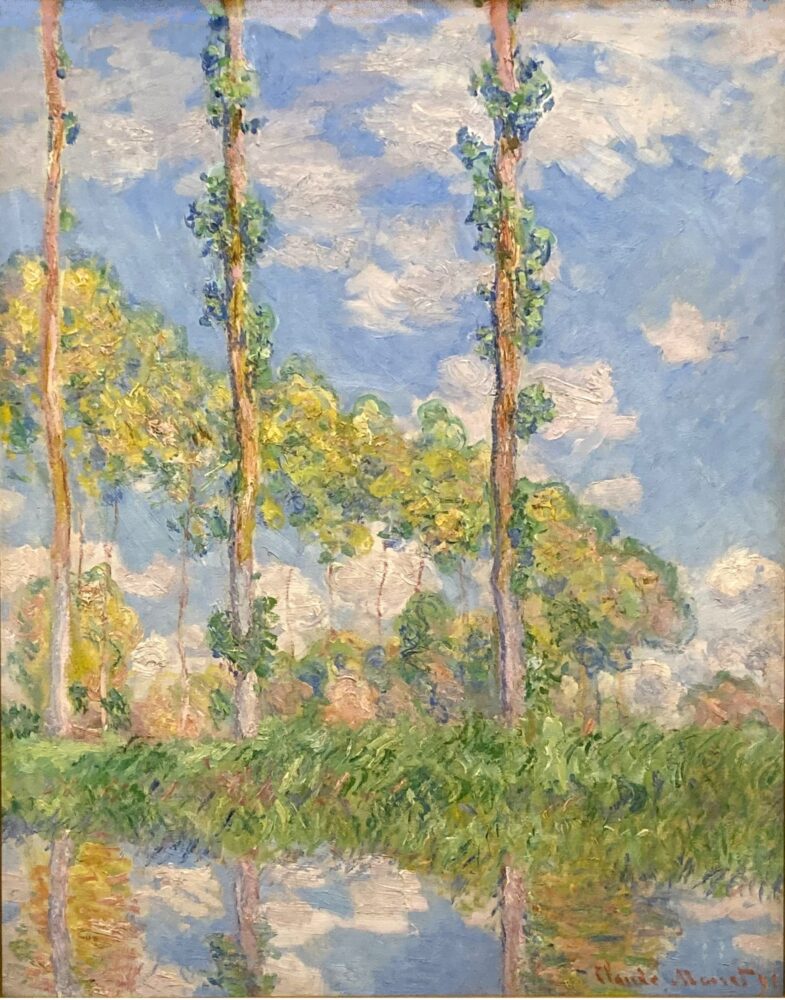

Kanagawa Prefecture

Pola Museum of Art

” The Water Lily Pond ” (1899)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

One of the highlights of the Pola Museum of Art is this The Water Lily Pond.

The arched bridge at the center is the signature motif of Monet’s Early Water Lilies Series.

The perfectly balanced, almost symmetrical composition gives it a decorative elegance.

During this period, Monet was still relatively realistic in his approach.

Even with the bright colors, you can clearly feel the depth of the pond.

The fresh yellow-green of the reflected trees and the water lilies floating above the surface create a scene that feels almost weightless. It’s a wonderful example of the charm of Impressionism.

By the way, this arched bridge was something Monet built himself in his “water garden.”

The idea actually came from his love of Japanese woodblock prints.

From the mid-19th century onward, Japanese culture spread across Europe through World Expos, inspiring many Impressionist painters. Monet was no exception—he collected prints by Hiroshige, Utamaro, and others with great enthusiasm.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

” Water Lilies ” (1907), Pola Museum of Art

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

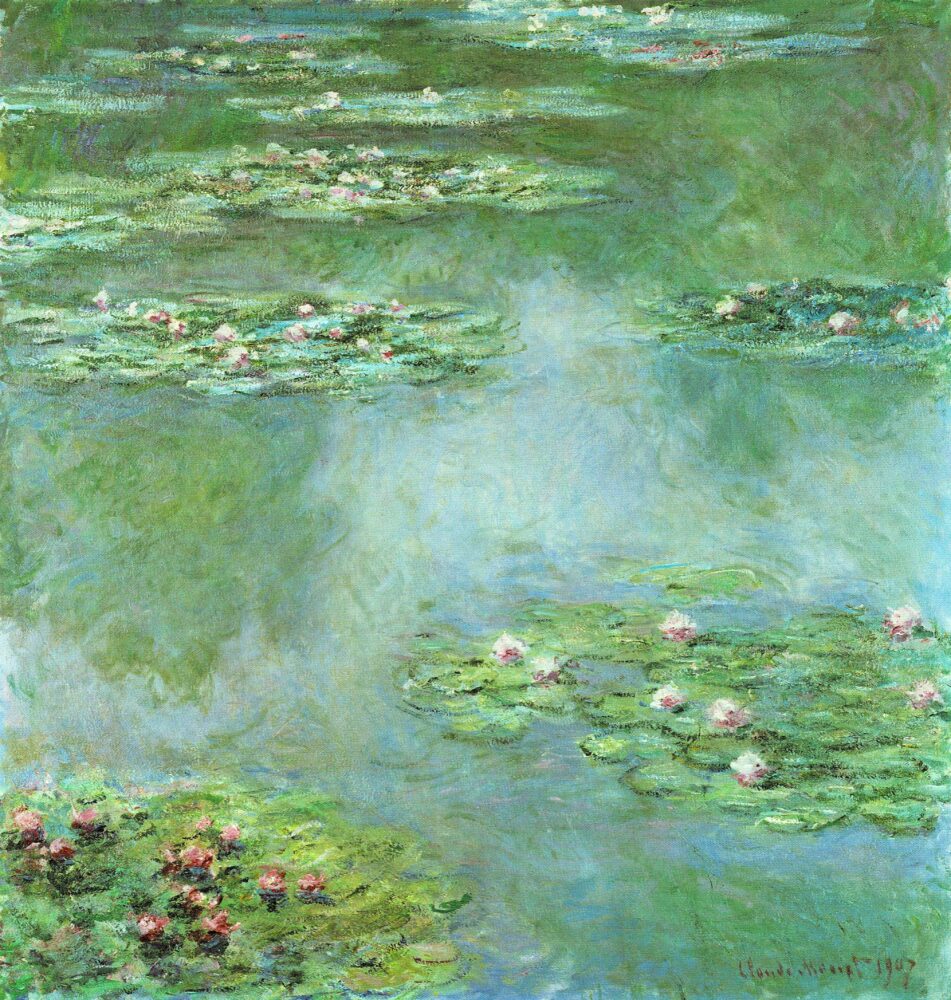

This painting belongs to Monet’s Second Water Lilies Series.

It was one of the 48 works exhibited at the landmark 1909 show Water Lilies: Series of Waterscapes in Paris.

When you compare it to the earlier The Water Lily Pond (1899), the stylistic shift becomes strikingly clear.

It’s not simply a difference in lighting. Monet’s interest had shifted toward capturing the delicate, ever-changing reflections on the water’s surface.

Monet himself expressed this idea beautifully:

” The essence of the motif is the mirror of water, whose appearance is altered at every moment by the fragments of sky reflected in it, spreading life and movement.

Source: Maison et jardins de Claude Monet, author’s translation

The passing cloud, the breeze that freshens, the squall that threatens and falls, the wind that blows and suddenly dies down, the light that fades and is reborn—so many causes, imperceptible to the eyes of the uninitiated, that transform the color and distort the surface of the water. “

Most painters would look for complex light effects in landscapes or still-life subjects.

But Monet chose something far simpler—the surface of water.

And in that simplicity, he found an “infinite canvas” that allowed him to capture the mysterious nature of light itself.

▶ Read more about the Pola Museum of Art here.

Chubu Region

Gifu Prefecture

Hikaru Museum

” Water Lilies ” (1903-1919)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

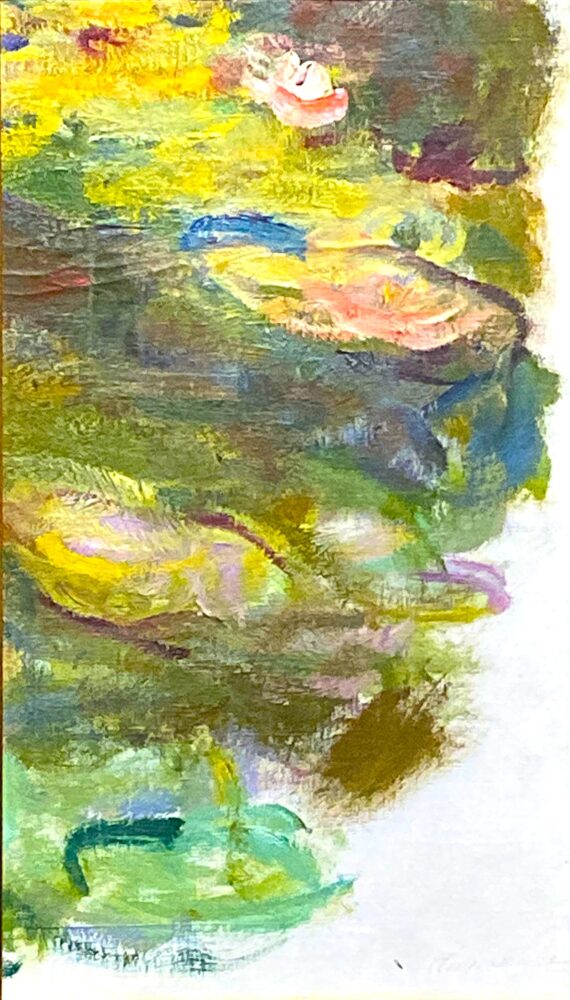

This Water Lilies painting from the Hikaru Museum in Takayama is quite unique.

Its date is uncertain—it could have been made anytime from the late “Second Series” to the period of the “Large Decorative Panels.” However, its flat and decorative style suggests it was painted after the later years of the Second Series.

What really stands out is the extremely vivid color.

Around 1908, Monet began experiencing serious eye problems, and he was diagnosed with cataracts in 1912. By 1915, he even wrote:

“ I no longer perceived colors with the same intensity… I no longer painted light with the same accuracy. Reds appeared muddy to me, pinks insipid, and the intermediate and lower tones escaped me. “

Source: Optometrists.org. “Claude Monet’s Art and the Impact of Cataracts.” Accessed November 16, 2025.

A good example is Irises (1914–1917), where the unusually harsh colors are often linked to Monet’s cataracts.

Private Collection

It’s important to remember that Monet was not the type of painter who exaggerated colors on purpose, like the Fauves or the Symbolists. He painted what he actually saw.

That means the striking colors from this period were not a stylistic choice—they were the direct result of how his vision had changed.

Even though illness affected his sight, this was still the “reality Monet saw.” In that sense, the Hikaru Museum’s Water Lilies is a precious work that reflects the artist’s late-life vision.

▶ Read more about Hikaru Museum here.

Kinki Region

Kyoto Prefecture

Asahi Group Oyamazaki Villa Museum of Art

” Water Lilies ” (1907)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

This painting is part of Monet’s “Second Series.”

In the winter of 1906, Monet’s wife Alice wanted to escape the cold of northern France and spend time somewhere warmer. But Monet refused—he wanted to stay in Giverny to observe the buds of his water lilies. His dedication to painting was incredible.

This work was created during that time.

You can almost imagine Monet saying “There it is!” as he captured the moment when the lilies slowly opened in the chilly air.

” Water Lilies ” (1914-1917), Oyamazaki Villa Museum of Art

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

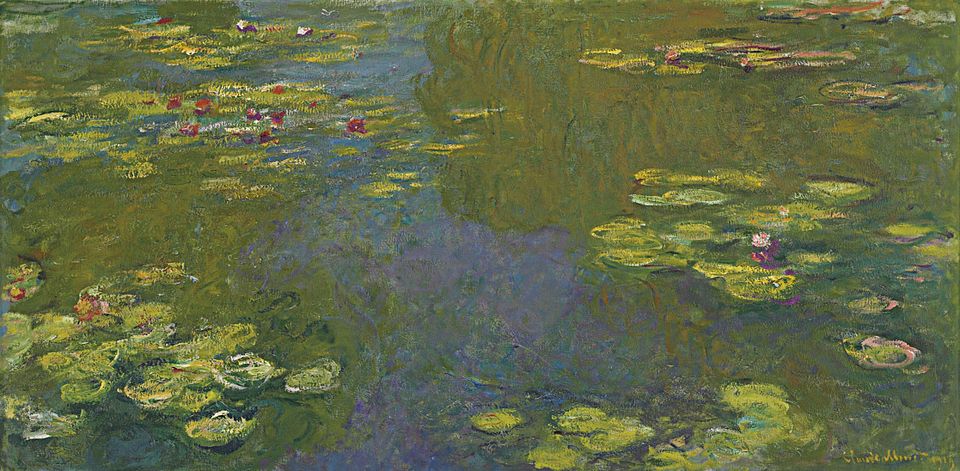

Starting in 1914, Monet fully committed himself to creating the Large Decorative Panels, called “Grand Décoration“.

The final version is now displayed in the famous “Water Lilies Rooms” at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris. The scale is massive—about 2 meters high and 91 meters long in total.

The works held at the Oyamazaki Villa Museum were painted right around the time Monet began enlarging his compositions.

Some measure nearly 200 cm on one side—four times larger than the smaller pieces he painted around 1907.

These were no longer “paintings for your living room.”

They were artworks designed for entire rooms. Monet’s ambition and sense of scale appear directly on the canvas.

▶ Read more about the Oyamazaki Villa Museum here.

Osaka Prefecture

Kuboso Memorial Museum of Arts, Izumi

” Water Lilies ” (1907)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

This Water Lilies belongs to the “Second Series” and shares almost the exact composition with works from the former DIC Kawamura Memorial Museum and the Artizon Museum. Monet often painted the same spot again and again under different light, and this piece clearly reflects that process.

Look closely at the contrast between the lower and upper parts of the painting.

The water surface at the bottom shows soft colors—orange, yellow-green, and pale blue—scattered like a prism, capturing the delicate flicker of light. Meanwhile, the upper area features bold strokes of red and orange from a sunset peeking through willow branches, giving the painting a dramatic energy.

Around this time, Monet began moving away from the deep spatial landscapes seen in the “First Series,” shifting toward a flatter and more abstract style. If you didn’t know it was a pond, you might even ask, “Is this really the water’s surface?”

But that sense of uncertainty is exactly the result of Monet exploring the depth and mystery of his “water mirror.”

▶ Read more about the Kuboso Memorial Museum of Arts, Izumi here.

Chugoku Region

Okayama Prefecture

Ohara Museum of Art

” Water Lilies ” (1906)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

The Ohara Museum of Art—known as the first Western art museum in Japan—also owns a Second Series painting from Monet’s Water Lilies.

This particular work was acquired through direct negotiation with Monet himself by the Western-style painter Torajirō Kojima, the key figure behind the museum’s collection. When the Ohara Museum of Art opened in 1930, the year after Kojima’s death, this painting went on display and has remained on view ever since—a truly historic piece.

For Japan at the time, opportunities to see original Western paintings were extremely limited. This Water Lilies must have made a strong impression. In fact, it’s considered one of the works that first shaped the Japanese public’s association of “Monet = Water Lilies.”

Monet found endless variety in the simple motif of a “water surface,” capturing the ever-changing play of light. Today, he is one of the most beloved artists in Japan—and perhaps part of that appeal comes from something that resonates with Japanese aesthetics, like the beauty of ma (negative space) and visual stillness.

▶ Read more about the Ohara Museum of Art here.

Shikoku Region

Kagawa Prefecture

Chichu Art Museum

” Water-Lily Pnd ” (1915-1926)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

One of Monet’s greatest late-life projects was the series of monumental Water Lilies installed in the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, called “Grand Décoration“.

This Water-Lily Pond at the Chichu Art Museum is one of the “candidate works” created during that ambitious project.

It was originally intended for the west wall of the first exhibition room in the Orangerie’s Water Lilies galleries—where Setting Sun now hangs. Although it was not selected in the end, the many layers of overpainting reveal how persistently Monet worked on it, making it a powerful and deeply considered piece.

” Water-Lily Pnd ” (1917-1919), Chichu Art Museum

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Monet began seriously developing his immersive Grand Décoration project in 1914, aiming to create large-scale paintings that would surround viewers completely.

Before reaching the final compositions now in the Orangerie, he produced a remarkable number of studies and experiments.

This work is one of them, and Monet created several pieces with the same composition during this period.

Comparing them is fascinating—the impressions differ so dramatically that they almost feel like entirely different paintings.

In the Chichu version, the contrast between the reflected trees and the sky is striking, and the water-lily blossoms blend with cool blue and violet tones to create an almost dreamlike atmosphere.

Even with the same motif, changes in light—and Monet’s shifting perspective—result in completely different expressions. That endless variety is one of the reasons the Water Lilies series feels so profound.

” Water-Lilies, Reflection of a Weeping Willow ” (1916-1919), Chichu Art Museum

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

This work is another study for the “Grand Décoration“.

The fiery brushstrokes forming the silhouette of the willow reflected on the water create a strong, memorable impression.

In the Orangerie’s Grand Décoration, there are several panels that show trees reflected on the water.

However, none of them emphasize the tree’s silhouette as clearly as this one.

In that sense, the strong, distinct reflection of the willow is a feature unique to this painting.

Monet painted it during World War I.

As he watched many young French men leave for the battlefield, he was deeply shaken—and during this time he created a series of Weeping Willows, symbols of mourning and renewal.

This Water-Lilies, Reflection of a Weeping Willow may also carry Monet’s hopes and prayers, embedded in the softly trembling willow reflections.

Musée Marmottan Monet

” Water-Lilies, Cluster of Grass ” (1914-1917), Chichu Art Museum

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

This painting is one of the early studies Monet created when he first began working on the “Grand Décoration”.

When we think of Water Lilies, we tend to focus on the water surface. But the Orangerie murals also include Weeping Willows.

Here, however, the central motif is not the lilies but the thick clumps of grass growing at the edge of the pond.

At this stage, Monet seemed eager to expand the canvas outward, embracing all forms of life in his garden. He may have been testing just how far the pictorial space could reach.

” Water Lilies ” (1914-1917), Chichu Art Museum

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

This work is another early study for the Grand Décoration.

The overall tone is gentle, with the contrast intentionally softened, giving the painting a calm and peaceful atmosphere.

The soft green shapes in the foreground may be leaves from trees reflected on the surface of the pond.

Blended with the blue of the sky, those delicate green hues evoke the quiet, refreshing air of an early-summer garden.

Kyushu Region

Fukuoka Prefecture

Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art

” Water-Lilies, Reflection of a Weeping Willow ” (1916-1919)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

The Water-Lilies, Reflection of a Weeping Willow at the Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art is a study for Monet’s Grand Décoration, painted around the same time as the work with the same title at the Chichu Art Museum.

A large painting of this same motif is also preserved at the Musée Marmottan Monet. Together, they show just how deeply Monet explored the theme of “a weeping willow reflected on the water,” experimenting again and again to capture the right expression.

Around the time this piece was created, Monet had initially planned to donate only two Grand Décoration panels to the French government.

But when the statesman Georges Clemenceau visited Giverny to select them, he was stunned by the sheer number of monumental canvases lining Monet’s studio.

Their conversation soon shifted from “choosing two works” to a much more ambitious idea: creating an entire room dedicated to the paintings themselves.

This moment became the starting point for what would later become the iconic Water Lilies Room at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.

Kagoshima Prefecture

Kagoshima City Museum of Art

” Water Lilies ” (1897-1898)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

The last work in this guide is an early Water-Lilies painting, housed at the Kagoshima City Museum of Art.

Before the “First Series,” Monet painted freshly opened water lilies with a sense of freedom and spontaneity. This early piece still carries that mood.

A pure white blossom floats on a dim, quiet pond. Blue-tinted leaves and petals surround it, giving the scene a cool, refreshing atmosphere.

Water lilies bloom in the morning and close in the early afternoon.

From this single canvas, you can almost feel the peaceful early-morning air of Monet’s garden in Giverny.

▶ Read more about the Kagoshima City Museum of Art here.

Conclusion

We’ve now explored 26 Water-Lilies paintings preserved in museums across Japan.

How was the journey?

Monet is said to have created around 250 Water-Lilies works in his lifetime.

When you realize that roughly one-tenth of them are here in Japan, it feels truly remarkable.

Another point worth noting is that several of the works introduced in this guide were once considered candidates for the Grand Décoration at the Musée de l’Orangerie.

Monet carefully selected the final murals to design the entire space as a unified artwork—but that does not mean the works left out of the final selection are in any way inferior.

If anything, they preserve the “living traces” of Monet’s creative process—the drafts, experiments, and hesitations that shaped one of the most ambitious projects in art history.

If you live near a museum that houses one of these Water-Lilies paintings, I truly recommend paying a visit.

You may find that, as the quiet water surface shimmers before you, your own thoughts and feelings settle into a calm, peaceful place.

References

- Ross King, Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies. Japanese translation by Nachiko Nagai. Aki Shobo, 2018.

- Hiroo Yasui, The World of Monet’s “Water-Lilies” (Illustrated Edition). Sogensha, 2024.

Related Articles

▶ Learn more about Monet’s Water-Lilies and the Grand Décoration

▶Read articles about the museums featured in this guide

▶The National Museum of Western Art

▶Artizon Museum

▶Tokyo Fuji Art Museum

▶Pola Museum of Art

▶Asahi Group Oyamazaki Villa Museum of Art

▶Kuboso Memorial Museum of Arts, Izumi

▶Ohara Museum of Art

▶Kagoshima City Museum of Art

Comments