Hello and welcome back to Art Ohenro!

In the previous article (Part 3), we explored van Gogh’s time in Arles, where his art reached full maturity. It was a period filled with both creative breakthroughs and emotional turmoil — especially his dramatic fallout with Gauguin.

Now, in this final chapter, let’s follow van Gogh through his Saint-Rémy and Auvers periods, the closing years of his remarkable life.

(If you missed the previous part, check it out first!)

What Were van Gogh’s “Saint-Rémy and Auvers Periods”?

This stage marks the final chapter of Van Gogh’s life.

After suffering a mental breakdown in Arles, Van Gogh entered the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole Asylum in southern France, located in the quiet town of Saint-Rémy. There, he spent his days painting and reflecting deeply on his own emotions while living in isolation.

After leaving the asylum, he moved north to the small village of Auvers-sur-Oise, just outside Paris, to continue his recovery. Surrounded by new scenery, Van Gogh created some of his most powerful works — but also faced the final days of his life.

Let’s trace his journey together.

Saint-Rémy – Deep Thoughts in Silence

Saint-Paul-de-Mausole Asylum

The Saint-Paul-de-Mausole Asylum, where Vincent van Gogh stayed, was originally a monastery before being converted into a psychiatric hospital in the early 19th century.

On May 8, 1889, at the age of 36, van Gogh voluntarily admitted himself to the asylum.

Before his admission, his brother Theo was deeply worried, fearing that “life in such a place could never be comfortable.” But once inside, Vincent seemed surprisingly calm and quickly adapted to the new environment. Soon after arriving, he wrote to Theo:

“I wanted to tell you that I think I’ve done well to come here, first, in seeing the reality of the life of the diverse mad or cracked people in this menagerie, I’m losing the vague dread, the fear of the thing. And little by little I can come to consider madness as being an illness like any other.” 1

He also found emotional comfort in the warm letters he received from Johanna, Theo’s wife.

At first, Vincent feared that Theo’s marriage meant he would be “abandoned” by his brother, but Johanna’s kind and sincere letters gradually eased his heart.

Finding Beauty in Silence – Irises

Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum

During a calm period without major attacks, Van Gogh found inspiration in the blooming irises in the asylum garden.

The deep blue-violet flowers stood out beautifully against the pinkish soil and green leaves — a harmony that instantly drew his artistic attention.

He soon began painting what would become one of his most famous works, Irises.

The way he captured the flowers from the side suggests that he might have crouched down, quietly observing them at eye level.

Every petal is painted with care — soft folds, bold outlines, and subtle color shifts.

The entire canvas reflects Van Gogh’s deep affection and intense gaze toward the flowers.

Quiet Reflections and the Search for Meaning

In Arles, Van Gogh was surrounded by new artistic influences — Impressionism, Japanese prints, and Gauguin’s Cloisonnism — all of which fueled his creativity.

But in Saint-Rémy, the atmosphere was completely different.

Cut off from the outside world, he lived in stillness, turning his thoughts inward.

Through painting, he began to explore deeper questions: What is art? What does it mean to create?

His curiosity eventually reached ancient art, especially Egyptian art, which fascinated him with its simplicity and spiritual strength.

He once wrote to Theo:

“Now Egyptian art, for example, what makes it extraordinary, is it not that those calm, serene kings, wise and gentle, patient, good, seem unable to be other than they are; eternally farmers who worship the sun…

the Egyptian artists thus have a faith, working from feeling and instinct, they express all these intangible things: goodness, infinite patience, wisdom, serenity, with a few masterly curves and marvellous proportions.” 2

This quote shows how Van Gogh was drawn to the pure power of form and the spiritual act of painting itself.

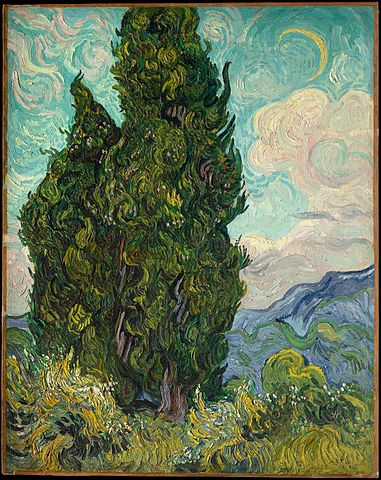

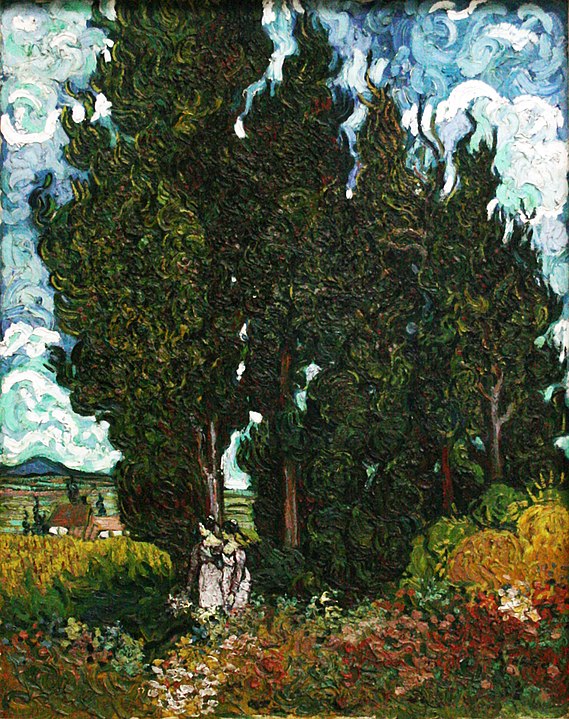

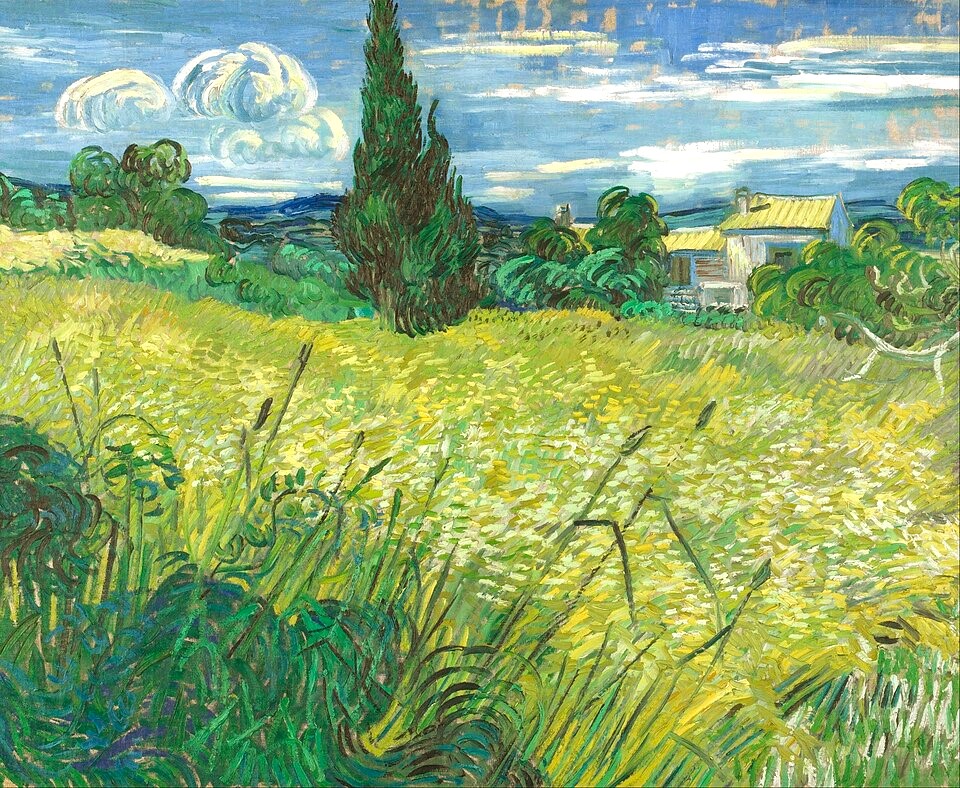

The next motif that caught his eye would become another of his great symbols — the cypress tree.

The Cypress Tree – A Symbol of Strength and Struggle

Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“The cypresses still preoccupy me, I’d like to do something with them like the canvases of the sunflowers because it astonishes me that no one has yet done them as I see them.

It’s beautiful as regards lines and proportions, like an Egyptian obelisk.“ 3

During his stay in Saint-Rémy, van Gogh was captivated by the tall cypress trees rising around the hospital grounds.

He was fascinated by their deep green tones, their dense texture, and their striking presence in the bright landscape — almost like “black flames” reaching toward the sky.

The painting above, Cypresses, was created around the time he was first allowed to leave the hospital grounds.

Against a vivid blue sky and bright fields, the swirling brushstrokes of the dark green trees stand powerfully, filling the scene with movement and energy.

When Van Gogh spoke of the “proportions” of the cypress, he likely meant its structural beauty — the flowing lines of its leaves, the rhythm of its curves, and its overall balance.

Perhaps he saw in it a reflection of nature’s harmony and order, where every small motion contributes to a living whole.

Even the sky and earth around it seem to pulse with the same rhythm, uniting everything into one vibrant organism.

In European culture, cypress trees are often associated with death and mourning, leading some to interpret his paintings as symbols of despair.

However, Van Gogh’s letters show little trace of negativity.

Instead, he wrote to Theo with enthusiasm, calling the trees “splendidly green” and “tall and solid.”

For Van Gogh, the cypress was not a symbol of death — it was a symbol of resilience and life.

Amid illness and solitude, he found in these trees a sense of strength and endurance, something that seemed to mirror his own determination to keep creating.

Collection of the Kröller-Müller Museum

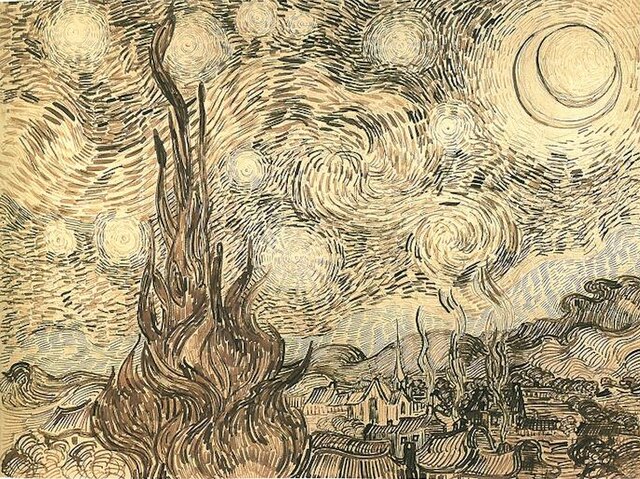

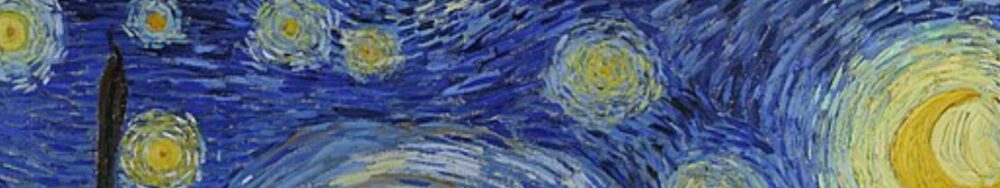

The Starry Night

Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Painted during his stay at the asylum in Saint-Rémy, The Starry Night is now one of the most famous paintings in the world.

But at the time, it might have felt to Van Gogh like a bold — even risky — experiment.

Because patients were not allowed to go out at night or bring paint into their rooms, Van Gogh could only sketch the view of the eastern sky from his window. He then completed the painting during the day, relying on his memory and imagination.

Collection of the Shchusev Museum of Architecture

The result is a dreamlike landscape — the Alpilles mountains in the background, a quiet village below, and a church steeple (inspired by the church of Saint-Martin) that he added from imagination.

The contrast between the vast swirling sky and the stillness of the village creates a dramatic, almost spiritual atmosphere.

In his earlier Cypresses, the trees seemed to move and twist.

But here, the sky itself seems alive — flowing, swirling, and breathing with energy.

The moon and stars pulse like living things.

This daring expression may have been Van Gogh’s small act of “revenge” on Gauguin, who once told him to “paint more from imagination.”

However, Theo’s reaction was not what Vincent hoped for.

“I quite understand what it is that attracts you in your recent paintings of moonlit villages and mountains {i.e., “The Starry Night”}. But I think that searching for a certain style takes away the true feeling of things.” 4

Normally, Van Gogh might have snapped back at such criticism.

But this time, he quietly admitted his frustration in a letter to his friend Émile Bernard:

“When Gauguin was in Arles, I once or twice allowed myself to be led into abstraction… But that’s enchanted ground, — my good fellow — and one soon finds oneself up against a wall…

However, once again I’m allowing myself to do stars too big, &c., new setback, and I’ve enough of that.” 5

Today, The Starry Night is the ultimate symbol of van Gogh’s genius.

But in his eyes, it was an overreaching, imperfect experiment.

He didn’t even submit it to the Indépendants Exhibition or the “Les Vingt” group show in Brussels in 1890.

Seizures and the Wheat Fields

The Recurrence of His Seizure

img: by Saint Rémy de Provence Tourisme at French Wikivoyage

At first, life in the asylum seemed to calm Van Gogh.

He was painting regularly again and even began to believe that his attacks would never return.

Yet, somewhere deep inside, he may have sensed that another storm was coming.

In early June, he went into the town of Saint-Rémy for the first time in months, accompanied by a hospital attendant.

Afterward, he wrote:

“I once went into the village — accompanied, at that. The mere sight of the people and things had an effect on me as if I was going to faint, and I felt very ill.” 6

It’s unclear whether his doctor fully understood how serious this was.

In early July, Van Gogh was granted permission to travel briefly to Arles — to collect his belongings and paintings left behind.

A few days after returning, the seizures came back.

Unlike the earlier episode in Arles, which lasted one or two weeks, this one was far more severe.

From mid-July to late August — for more than a month — Van Gogh was unable to paint or even write letters.

During the attacks, he was confused and reportedly drank lamp oil and paint, alarming the doctors.

Dr. Peyron considered this a suicide attempt and temporarily banned Van Gogh from entering his studio.

When he finally recovered in late August, he managed to send a letter to Theo.

Because sharp objects were forbidden, he wrote it in black chalk instead of ink.

“I’m very deeply distressed that the attacks have recurred when I was already beginning to hope that it wouldn’t recur…

For many days I’ve been absolutely distraught, as in Arles, just as much if not worse, and it’s to be presumed that these crises will recur in the future, it is ABOMINABLE.” 7

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

Wheat Fields and the Shadow of Death

After his seizures finally calmed down and he was allowed to return to his studio, Van Gogh began working on Wheatfield with Reaper.

It may not be one of his most famous paintings, but in fact, he painted three versions of this scene in a short period of time — a clear sign of how deeply it meant to him.

The first version, now in the Kröller-Müller Museum, was created in June 1889, before his seizure. Vincent described it as “the brightest of all the paintings I have done so far.”

But when he painted the same motif again after the seizure, his emotions had changed. In a letter to his brother Theo, he wrote:

“I then saw in this reaper – a vague figure struggling like a devil in the full heat of the day to reach the end of his toil – I then saw the image of death in it, in this sense that humanity would be the wheat being reaped.” 8

For Van Gogh, the wheat field was no longer just a landscape.

It had become a symbol of life’s fragility — of mortality itself — quietly woven into the rhythm of nature.

Over time, he began to see the life cycle of wheat as a mirror of human life. In a letter to his sister Willemien, he explained:

“Their {i.e.,wheat’s} story is ours, for we who live on bread, are we not ourselves wheat to a considerable extent, at least ought we not to submit to growing, powerless to move, like a plant, relative to what our imagination sometimes desires, and to be reaped when we are ripe, as it is?” 9

To live, to grow, and to be harvested one day.

Van Goght accepted this not as something tragic, but as a natural part of existence — a quiet, almost peaceful philosophy that emerged in his late works.

He also told Theo:

“I think it (i.e.,”Wheatfield with Reaper”) will be one that you’ll place in your home – it’s an image of death as the great book of nature speaks to us about it – but what I sought is the ‘almost smiling’.” 10

(Here, “the book of nature” refers to the idea that truth can be found in nature itself.

The phrase “almost smiling” comes from a French writer’s description of the death of the painter Delacroix.)

For Van Gogh, death was not something terrifying or final — he wanted it to be like a gentle smile, a peaceful ending to the story of life.

And to Van Gogh, nature was like family.

Just as people find comfort and strength from their loved ones, Van Gogh found the same in the earth, the grass, and the golden wheat fields around him.

“…what I hope for once I set myself to having some hope, it’s that the family will be for you what nature is for me, the mounds of earth, the grass, the yellow wheat, the peasant…” 11

Even painful things like illness or death seemed less frightening to him when seen as part of nature’s great cycle.

Through The Wheat Field with a Reaper, Van Gogh seemed to reflect deeply on himself — and as a result, he began to face his illness with new understanding.

Later, he began to notice a pattern in his illness:

“I consider a new crisis likely in the winter, i.e. in 3 months.” 12

Sadly, his prediction would turn out to be right.

A Time of Change

Recognition at the Salon des Indépendants and Les Vingt

In the fall of 1889, while still in the asylum at Saint-Rémy, Vincent van Gogh sent two paintings to the Salon des Indépendants in Paris — Irises, painted in the hospital garden, and Starry Night over the Rhône, from his days in Arles.

Both were submitted through his brother Theo and displayed alongside works by Seurat, Signac, and Toulouse-Lautrec.

The response from visitors was very positive. Theo wrote to Vincent:

” The Irises were seen by a lot of people who talk to me about them. “ 13

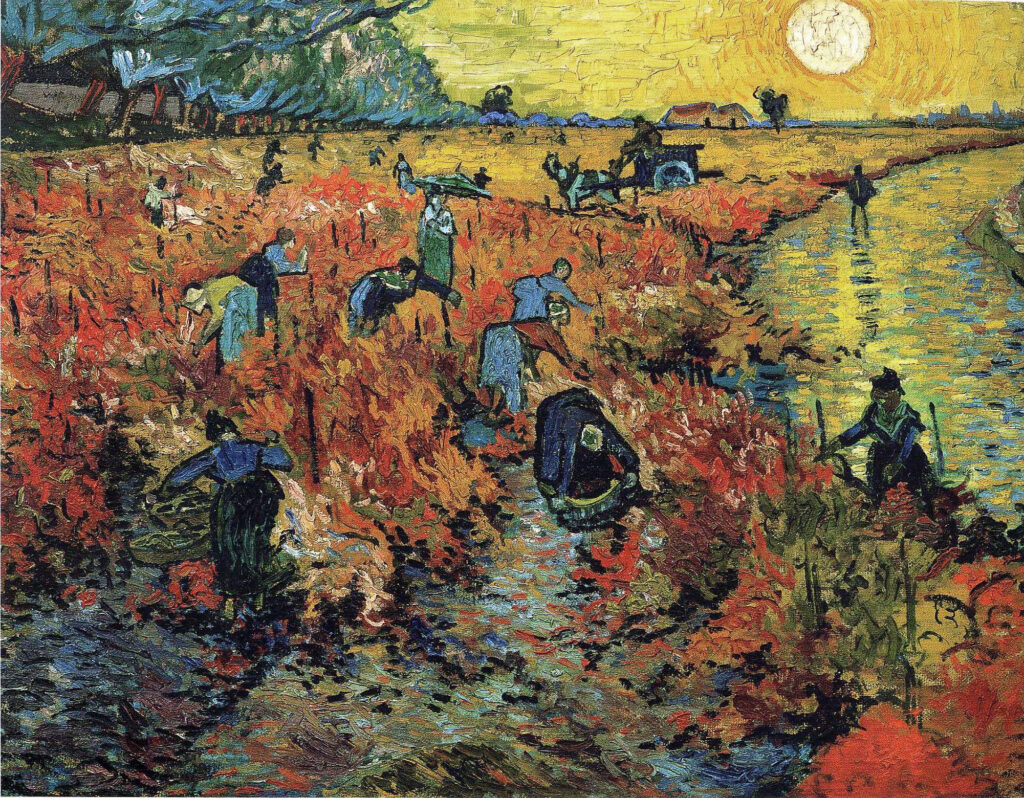

In January 1890, Van Gogh was also invited to exhibit six paintings at the avant-garde Belgian art group Les Vingt (The Twenty), including Sunflowers and The Red Vineyard.

Among works by Cézanne, Pissarro, Renoir, and Toulouse-Lautrec, his paintings drew attention — and The Red Vineyard sold for 400 francs, marking the first and only time Van Gogh sold a painting during his lifetime.

In a letter to his mother, he modestly wrote that the price was “too low,” but in truth, he must have been overjoyed.

The First Signs of Recognition

Around the same time, in August 1889, the Dutch art magazine De Portefeuille published an article introducing Van Gogh.

Written by Theo’s friend Joseph Isaacson, it harshly criticized the state of Dutch art as “factory-made products,” but praised Van Gogh as:

” I know one, a unique pioneer; he stands alone to struggle in the great night. His name, Vincent, is for posterity. ” 14

Van Gogh, however, seemed a bit embarrassed by the attention.

He asked that “only a few words” be written about him, feeling that his work was “still not much to speak of.”

Then, in January 1890, the French journal Mercure de France published a passionate review by art critic Albert Aurier.

He wrote:

” we are thus able to infer legitimately from Vincent van Gogh’s works themselves his temperament as a man… What characterizes his works as a whole is its excess . . . of strength, of nervousness, its violence of expression. In his categorical affirmation of character of things, in his often daring simplification of forms, in his insolence in confronting the sun head-on, in the vehement passion of his drawing and colour, even to the smallest details of his technique, a powerful figure is revealed . . . masculine, daring, very often brutal . . . yet sometimes ingeniously delicate . . . .” 15

Van Gogh thanked Aurier politely but replied humbly:

” I rediscover my canvases in your article, but better than they really are — richer, more significant…

For the share that falls or will fall to me will remain, I assure you, very secondary. ” 16

Although Van Gogh longed for recognition, he was careful not to lose sight of his true goal — to paint truthfully.

He wrote to Theo:

” Aurier’s article would encourage me, if I dared let myself go, to risk emerging from reality more and making a kind of tonal music with colour, as some Monticellis are. But the truth is so dear to me, trying to create something true also, anyway I think, I think I still prefer to be a shoemaker than to be a musician, with colours. “ 17

Praise from the Masters

In March 1890, the Salon des Indépendants opened again in Paris.

Van Gogh’s ten submitted works were widely admired — Claude Monet even called them “the best paintings in the entire exhibition.”

Paul Gauguin, who also visited the show, was so moved that he proposed exchanging one of his works for Van Gogh’s The Ravine of the Peyroulets.

He wrote:

” I’ve looked most attentively at your works since we parted; first at your brother’s place and at the Independents’ exhibition… I offer you my sincere compliments, and for many artists you are the most remarkable in the exhibition. With things from nature you’re the only one there who thinks...

I would like to exchange with you for a thing of your choice.

The one I’m talking about is a mountain landscape. Two tiny travellers seem to be climbing up there in search of the unknown. It contains an emotion à la Delacroix, with a very evocative colour. Here and there red notes like lights, the whole in a violet note. It’s beautiful and imposing.

I’ve talked at length about it with Aurier, Bernard and many others. “

Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Van Gogh’s reputation was finally beginning to rise.

The success he had dreamed of as an artist was slowly becoming real.

Theo, overjoyed, wrote to share the good news — but this time, the reply never came.

Van Gogh was once again struggling with another attack of illness.

At the End of the Battle with Illness

Recurring Seizures

By December 1889, one year had passed since Vincent van Gogh suffered his first attack at the Yellow House in Arles.

In a letter to his sister Wil, he quietly confessed:

” it’s exactly a year since I had that attack, I certainly have no reason to complain about it too much, as things are going better at present. But from time to time, though, it’s to be feared that it may return. And this leaves the mind in a latent state of sensitivity. ” 18

As Christmas approached, his anxiety deepened.

The season reminded him of the warm family gatherings of his childhood in Zundert — but now he was alone in the hospital, uncertain when the next attack might strike.

He also carried painful memories from Nuenen, where his harsh words toward his father had led to deep regret after his father’s sudden death.

In another letter to his mother, Van Gogh wrote:

” I often have terrible self-reproach about things in the past, my illness being pretty much my own fault, and in any event it’s doubtful whether I can make amends for faults in any way… You and Pa have been so much, so very much to me, possibly more even than to the others, and I don’t seem to have had a happy nature. ” 19

Perhaps burdened by guilt and self-reproach, Van Gogh suffered another attack — again on Christmas Day, exactly one year after the first.

It subsided after about a week, but by late January 1890, the illness returned.

Dr. Peyron informed Theo that Vincent was “unable to paint or respond coherently.”

Then, in late February, Van Gogh suffered yet another attack — this time outdoors in Arles.

He had just finished Madame Ginoux from the Café de la Gare, based on a drawing left by Gauguin, and was on his way to deliver it when the seizure struck.

Three attacks in just a few months — the February one being the most severe.

Despite the risk, Van Gogh had insisted on going out, hoping to test himself.

In a letter to Wil three days before the incident, he wrote:

“ I hope so at least – towards the end of March. I’m going to try to go to Arles once more tomorrow or the day after tomorrow to see if I can bear the journey and ordinary life without the attacks recurring. Perhaps in my case I must strengthen my resolve not to want to have a feeble mind…

But when I read the article (i.e., Aurier’s) it made me almost sad as I thought: should be like this and I feel so inferior. ” 20

He wanted to regain a normal life — to prove to himself that he could overcome his illness and live among people again.

But the strain was too much.

There was no attendant with him during the trip, so no one knows exactly how the seizure occurred.

When he was found wandering in a dazed state in Arles, hospital staff from Saint-Rémy rushed to bring him back by carriage.

Dr. Peyron initially believed he would recover in a few days, but this time, it was different.

The seizure lasted for nearly two months — the longest and most serious one of his life.

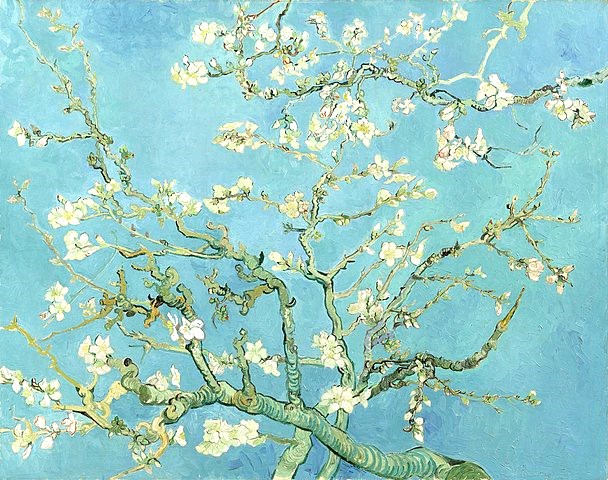

During this difficult time, a small ray of light appeared: on January 31, Theo and his wife Johanna welcomed a baby boy.

They named him Vincent after his uncle.

Just before the February attack, Van Gogh painted Almond Blossoms as a gift to celebrate his nephew’s birth — a painting filled with hope and tenderness.

Discharge from the Asylum

By late April 1890, Vincent van Gogh finally recovered from the long and painful series of attacks.

He began exchanging letters with Theo again, but his mood was still unstable. Some days, even reading a letter felt too heavy for him.

Still, he felt a strong desire to leave the hospital.

” I don’t know what to do or think. But I have a great desire to leave this place… Yes, I must try to leave here ” 21

He believed that moving to northern France would help him recover completely.

Theo didn’t oppose the idea. Instead, he left the decision up to Vincent, saying gently but realistically:

” you mustn’t think that you’ll find it (i.e., Understanding of Painting) otherwise anywhere, except as an exception… don’t have too many illusions about life in the north, after all every part of the world has its pros and cons. ” 22

Even so, Van Gogh’s determination was firm.

Theo wrote to Dr. Peyron, asking him to grant permission for Vincent’s discharge “unless there is serious risk.” The doctor agreed. On May 16, 1890, Van Gogh was officially released from the asylum.

In Dr. Peyron’s report, he described Van Gogh’s stay as follows:

“ The patient, though calm most of the time, has had several attacks during his stay in the establishment which lasted from two weeks to one month. During these attacks the patient was subjected to frightful terrors and tried several times to poison himself, either by swallowing the paints which he used for his work or by drinking kerosene which he managed to steal from the attendant while the latter refilled his lamps. His last fit broke out after a trip which he undertook to Arles, and lasted about two months. Between his attacks the patient was perfectly quiet and devoted himself with ardor to his painting. Today he is asking for his release to live in the North of France, hoping that its climate will be favorable. ” 23

Although less than a month had passed since his last attack, the doctor even wrote “Cured” in the medical notes.

Van Gogh soon began preparing for his departure.

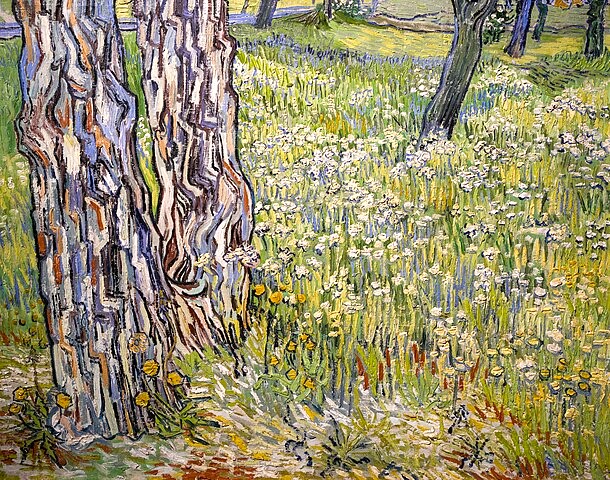

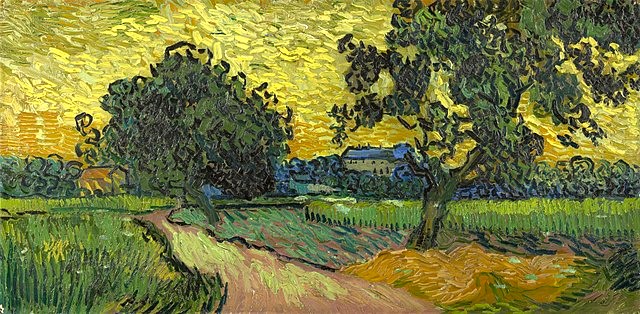

Before leaving, he painted several works—irises, cypresses, and spring landscapes—filled with the peaceful air of Saint-Rémy and his deep feelings for the place.

The Irises were soon exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants, receiving positive attention from critics.

Meanwhile, the Cypresses marked a new direction in his art, showing a boldness and clarity that would define his final works.

Life in Saint-Rémy had been a time of deep struggle, but also one of artistic growth and recognition.

Even as he longed to leave, Van Gogh felt a deep gratitude toward the land that had nurtured him.

“ I feel I have more confidence in my work than when I left (Paris), and it would be ungrateful of me to speak ill of the south, and I confess that it’s with great sorrow that I turn my back on it. ” 24

Such heartfelt words capture his sincerity.

And with thoughts of Theo, his sister-in-law Jo, and their newborn baby waiting in Paris, he began a new chapter of his journey.

” How much I want to see you again, and meet Jo and the baby. ” 25

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

Collection of the Kröller-Müller Museum

Collection of the Kröller-Müller Museum

To Auvers-sur-Oise

Warm Reunion in Paris

In May 1890, at the age of 37, Vincent van Gogh was finally discharged from the asylum in Saint-Rémy.

Theo worried about his brother’s condition and suggested hiring an attendant for the trip, but Vincent firmly refused.

He wanted to travel alone—so he boarded a night train bound for Paris.

Theo was so anxious that he couldn’t sleep all night, but Van Gogh arrived safely at his brother’s home.

Theo’s wife Johanna later recalled her first impression of him:

“ He looked healthy, smiled kindly, and appeared strong and determined—a broad-shouldered man. ” 26

She even said he looked much stronger than Theo, who was frail at the time.

The brothers joyfully reunited and went together to see the baby’s room.

Earlier that year, in January, Johanna had given birth to a son named Vincent, after his uncle.

This was Van Gogh’s first meeting with his newborn nephew.

He had already heard the news from Johanna’s letters, but seeing the baby in person deeply moved him.

As the two brothers looked quietly into the cradle, Johanna later wrote, “They both had tears in their eyes.”

It was a moment filled with silent emotion.

Van Gogh enjoyed his brief time with family, but soon he began to feel that the noise and tension of Paris were not good for his health.

Just three days later, he decided to leave the city and move somewhere more peaceful.

His destination was Auvers-sur-Oise, a quiet village northwest of Paris—

the place that would become the final chapter of his life.

The Final Stage: Auvers-sur-Oise

While still in the asylum, Van Gogh had written to Theo about where he might live after discharge.

Theo consulted their friend, the painter Camille Pissarro, who recommended a doctor living in Auvers—Dr. Paul Gachet.

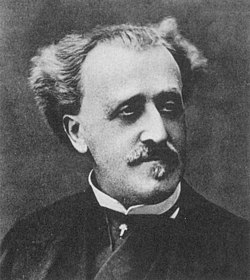

Dr. Gachet was not just any doctor.

He was a physician and amateur painter, and a friend to artists like Pissarro and Cézanne.

A man who loved art and understood the mind—he seemed the perfect person to care for Vincent.

Theo thought Auvers would be an ideal place for his brother:

close enough to Paris (about 30 kilometers away) yet calm and full of nature.

Auvers was a peaceful village surrounded by green hills and a small river.

Many artists—Charles-François Daubigny, Camille Corot, Cézanne, and Pissarro—had once painted its charming countryside.

Van Gogh immediately fell in love with the scenery:

” Auvers is really beautiful – among other things many old thatched roofs, which are becoming rare. ” 27

Collection of the Hermitage Museum

Portraits in Auvers

In Auvers, Vincent van Gogh met Dr. Paul Gachet—a man as eccentric as he was passionate about art.

At 61, Gachet had dyed blond hair, kept a house overflowing with cats, dogs, chickens, and rabbits, and even owned his own printing press. He was not only a physician but also an amateur painter and a close friend of artists like Pissarro and Cézanne. An art-loving doctor, immersed in the creative world.

At first, Van Gogh found him “rather eccentric”, calling him “as ill and confused as I” But gradually, the two developed a sense of trust and friendship.

Van Gogh wrote that Gachet “will remain a friend,” while Gachet reassured him, “Such attacks are highly improbable, they do not recur, and everything is going completely well.”

Two unusual men, bound by art and understanding.

As was often the case when Van Gogh grew close to someone, he painted Gachet’s portrait. The doctor was deeply moved by the result—his own image rendered with Van Gogh’s unmistakable brushwork and colors.

whereabouts unknown

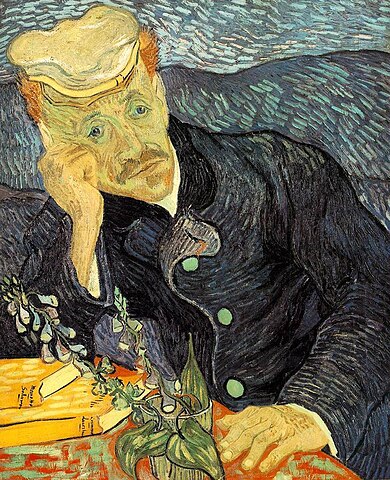

Van Gogh stayed at the Ravoux Inn, about one kilometer east of Gachet’s house. He also painted the innkeeper’s daughter, Adeline Ravoux.

During his time in Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh had mostly painted landscapes. But in Auvers, he turned again to portraiture. In a letter to his sister Wil, he wrote:

” What I’m most passionate about, much much more than all the rest in my profession – is the portrait, the modern portrait. I seek it by way of colour…

I would like to do portraits which would look like apparitions to people a century later. So I don’t try to do us by photographic resemblance but by our passionate expressions, using as a means of expression and intensification of the character our science and modern taste for colour. ” 28

Adeline herself thought the portrait didn’t look much like her.

Van Gogh was not aiming for photographic realism. Instead, he used color and emotion to express a person’s inner life.

In Auvers, he applied techniques he had learned from Japanese prints and cloisonnism—the use of clear outlines and bold color fields—along with the dynamic brushwork perfected in Saint-Rémy.

Sometimes his brushstrokes ignored smoothness or detail, but that boldness gave his portraits a sense of life—making them look like living apparitions.

After ten years of searching, Van Gogh’s pursuit of human expression finally reached a form of completion in Auvers.

Private Collection

A Letter from Paris

” We don’t know what we ought to do, there are questions…

when I work all day and still don’t manage to spare this good Jo from worries about money, since those rats Boussod & Valadon treat me as if I’d just started working for them and keep me on a leash. ” 29

In early July 1890, Vincent van Gogh received a heartbreaking letter from Theo.

His younger brother confessed that the family’s finances were tight, and that his job at the art firm Boussod & Valadon (formerly Goupil) had become unbearable.

Theo had been supporting Vincent for years, while also sending money to their mother and sisters—and now, with a wife and infant son, his expenses had grown. Under such pressure, he began thinking of leaving the company to open his own gallery.

But that was a risky dream, and the burden weighed heavily on him.

For Vincent, who had finally grown accustomed to life in Auvers, the letter came as a bolt from the blue. Unable to stand on his own as an artist, he had no choice but to rely on Theo— and that sense of guilt once again cast a shadow of anxiety over his heart.

Collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum

Visit to Paris — An Uneasy Apartment

Around the same time, Theo’s baby, Vincent Willem, fell ill, and Johanna, exhausted from caring for him, also became sick. With health and financial troubles piling up, Theo’s nerves were stretched thin.

Fortunately, both mother and child recovered, and Theo began to regain his calm. Wanting to make amends for his gloomy letter, he invited Vincent to visit Paris.

Van Gogh hesitated, writing, ” By coming straightaway I fear I would increase the confusion. ” 30

Still, concerned for his sister-in-law and nephew, he decided to go.

In Paris, critics such as Albert Aurier and the painter Toulouse-Lautrec came to see him. Aurier spoke with Vincent at length about his paintings, and Lautrec joined him for a friendly meal.

For a brief moment, it seemed like the world was bright again.

But tension soon returned.

A small argument broke out between Vincent and Johanna over where to hang one of his paintings. Johanna, though usually calm, was worn out from nursing her child and anxious about Theo’s plan to leave his job. Her patience snapped, and Vincent’s habit of fussing over details only added to the strain.

Later, Vincent van Gogh wrote (in a letter he never sent):

” Everyone seemed upset, struggling with their own burdens. I think it’s not so important to insist on having everything perfectly clear. I was surprised to see how hard you were trying to push through your disagreements. Can I do anything to help? Probably not… But if I’ve caused any trouble, or if there’s anything at all I can do, please tell me… ” 31

That unsent letter shows how deeply the encounter affected him.

There’s no evidence that Theo or Johanna criticized his dependence, but in the tense atmosphere of that apartment, Vincent must have felt the weight of being a burden once again.

His spirits sank.

Before meeting with the painter Guillemet as planned, Vincent quietly boarded the train back to Auvers.

The Final Works

Collection of the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

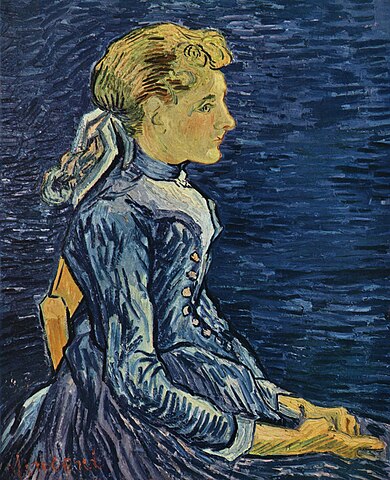

In May 1890, after leaving the asylum in Saint-Rémy, van Gogh arrived in Paris. Soon after, he visited the Salon du Champ-de-Mars, where he saw Pierre Puvis de Chavannes’s painting Between Art and Nature. Deeply impressed, he wrote to his sister Wil, enclosing a small sketch of the artwork and passionately describing what he felt.

” by seeing the painting, by looking at it for a long time one would think one was present at an inevitable but benevolent rebirth of all things that one might have believed in, that one might have desired, a strange and happy meeting of the very distant days of antiquity with raw modernity. ” 32

What caught Van Gogh’s attention was not only the spiritual message of the work but also its wide horizontal format, which created a strong sense of space.

He realized that such a composition could make the horizon in landscapes more dramatic and alive.

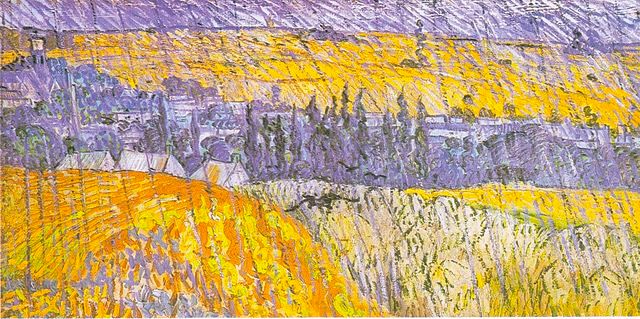

After moving to Auvers-sur-Oise, he began using this horizontal style in many of his works.

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

Collection of the Amgueddfa Cymru

Museum Wales

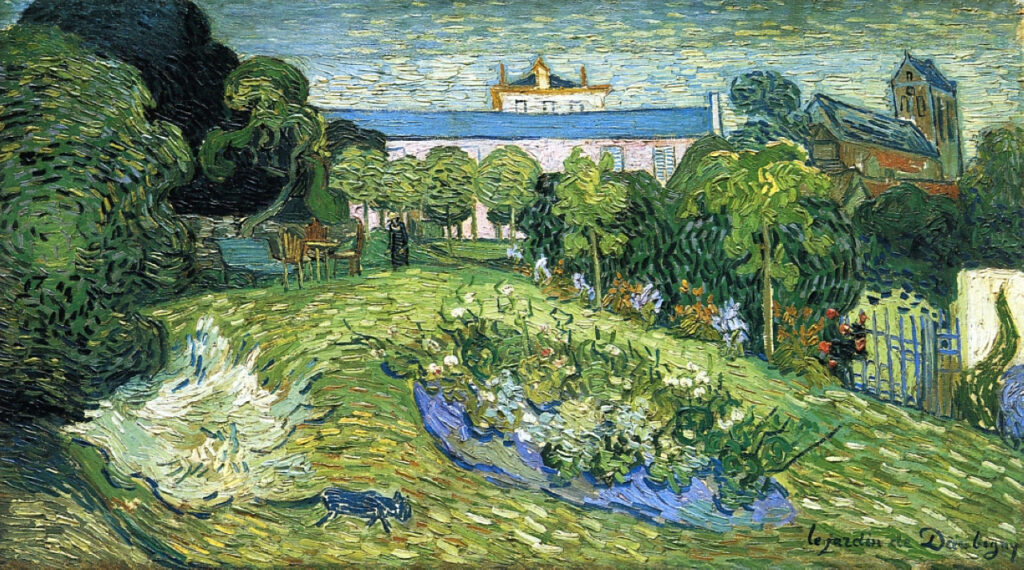

One of his last masterpieces, “Daubigny’s Garden,” was also painted on a long, horizontal canvas.

Charles-François Daubigny, a leading figure of the Barbizon School, was one of the artists Van Gogh admired most, along with Jean-François Millet.

Daubigny’s house was close to the Ravoux Inn, where Van Gogh was staying.

Although Daubigny had already passed away, his widow still lived there. Van Gogh often visited the garden and painted what deeply moved him.

He described the scene in detail in a letter:

” Foreground of green and pink grass, on the left a green and lilac bush and a stem of plants with whitish foliage. In the middle a bed of roses. To the right a hurdle, a wall, and above the wall a hazel tree with violet foliage.

Then a hedge of lilac, a row of rounded yellow lime trees. The house itself in the background, pink with a roof of bluish tiles. A bench and 3 chairs, a dark figure with a yellow hat, and in the foreground a black cat. Sky pale green. ” 33

Collection of the Kunstmuseum Basel

Van Gogh was also worried about Theo’s work and family life.

In the same letter, he wrote:

“I’d perhaps like to write to you about many things, but first the desire has passed to such a degree, then I sense the pointlessness of it.

I hope that you’ll have found those gentlemen (i.e., Theo’s employers at Boussod, Valadon & Cie.) favourably disposed towards you. ” 34

By this time, Theo had already decided to stay with Goupil & Cie, though he hadn’t told Vincent yet.

He probably wanted to wait—perhaps afraid that such news might upset his brother.

But no one could have imagined that this would be the last letter Vincent ever sent.

Death

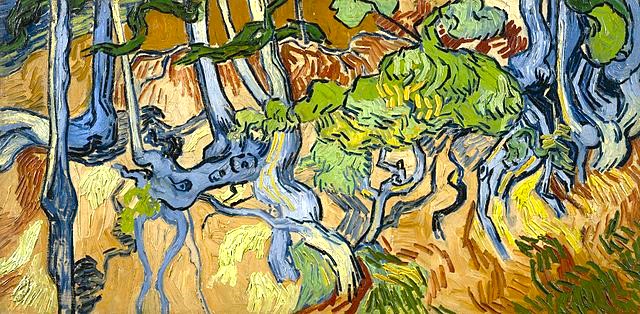

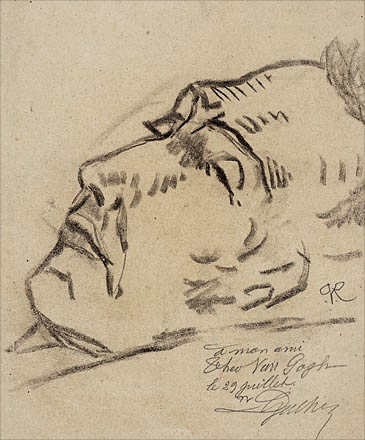

Believed to be Van Gogh’s final painting.

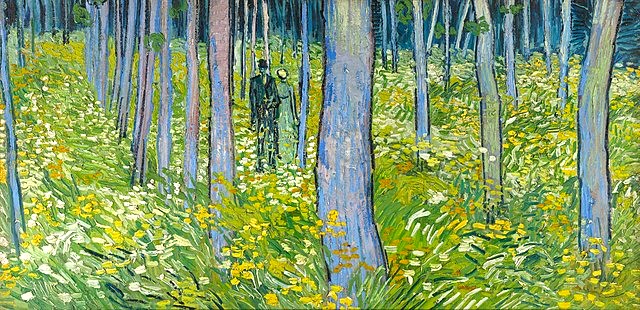

On July 27, 1890, at the age of 37, Vincent van Gogh finished his morning painting session and returned to the Ravoux Inn for lunch.

In the afternoon, he went out again with his painting tools, but that evening, he did not come back as usual.

As the sun set and the Ravoux family relaxed on the terrace after dinner, they suddenly saw Van Gogh emerge from the darkness.

He was bent over, holding his stomach, and went silently to his room.

Sensing something was terribly wrong, the innkeeper Gustave Ravoux went to check on him.

He found Van Gogh lying on the bed, moaning in pain. When asked what had happened, Vincent said:

” I wounded myself. “

Later, Adeline Ravoux, the innkeeper’s daughter, recalled the event in an interview published in Les Nouvelles littéraires (1954):

“Vincent had gone to the wheat field where he had painted previously, it was situated behind the Auvers chateau… The chateau was more than a half – kilometer from our house. It was reached by going up a steep hill, shaded by great trees. We do not know how far he got from the chateau. In the course of the afternoon, on the road that passes under the chateau wall – so my father understood – Vincent shot himself with a revolver and fainted. The freshness of the evening revived him. On all fours he sought the revolver to finish himself off, but could not find it (and it was not found the following day). Then Vincent gave up looking and came down the hill to regain our house. ” 35

Doctors Mazery and Paul Gachet were called to examine him.

The bullet had struck his left chest but had not passed through; it remained lodged inside.

The injury was serious and would normally have required surgery, but neither doctor was a surgeon, so little could be done.

Even so, Van Gogh remained conscious.

When Dr. Gachet asked for Theo’s address, Vincent refused at first, saying he didn’t want to trouble his brother.

The next morning, a young painter staying at the inn went to Paris to inform Theo in person.

Theo arrived in Auvers by noon on July 28.

He found Vincent sitting up in bed, calmly smoking his pipe.

They talked about Johanna and the baby, and Vincent even smiled a little.

But his condition soon worsened.

During that time, Theo wrote to Johanna:

” Poor fellow. He has had only a small share of happiness in life. There are no illusions left for him now. At times, the suffering becomes almost too heavy to bear, and he feels an overwhelming loneliness. ” 36

And at about 1:30 a.m. on July 29, 1890, Vincent van Gogh passed away peacefully, with Theo by his side.

It is said that Vincent’s final words were:

“This is how I would like to go.” 37

(by Dr. Paul Gachet)

Part 4 Summary: “At the End of the Journey”

Respect for the Masters of the Past

Inspired by Jean-François Millet, Van Gogh began painting for the poor and working people.

His ten years as a painter were a series of constant changes and challenges.

In Paris, he discovered Impressionism.

In Arles, he explored color and light.

And in Saint-Rémy, he developed a unique style that reflected his inner world.

Yet throughout these changing years, he always carried deep respect for the masters of the past—painters like Millet, Daubigny, and Delacroix of the Barbizon and Romantic schools.

In one of his letters from Saint-Rémy, he wrote:

” I mean by this that having reflected as time passed — I believe more than ever in the eternal youth of the school of Delacroix, Millet, Rousseau, Dupré, Daubigny, just as much as in the current one or even in artists to come. I scarcely believe that Impressionism will ever do more than the Romantics, for example…

This morning I saw the countryside from my window a long time before sunrise with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big. Daubigny and Rousseau did that, though, with the expression of all the intimacy and all the great peace and majesty that it has, adding to it a feeling so heartbreaking, so personal. These emotions I do not detest. ” 38

In the late 19th century, art styles changed rapidly—from Impressionism to Neo-Impressionism.

But Van Gogh’s heart always remained full of admiration for the masters who came before him.

That respect sustained him through illness and hardship and became the true source of his creative energy.

Collection of the Musée d’Orsay

His Attitude Toward Painting

Van Gogh’s sister-in-law, Johanna, said that his late works “gradually took on a sadder tone.”

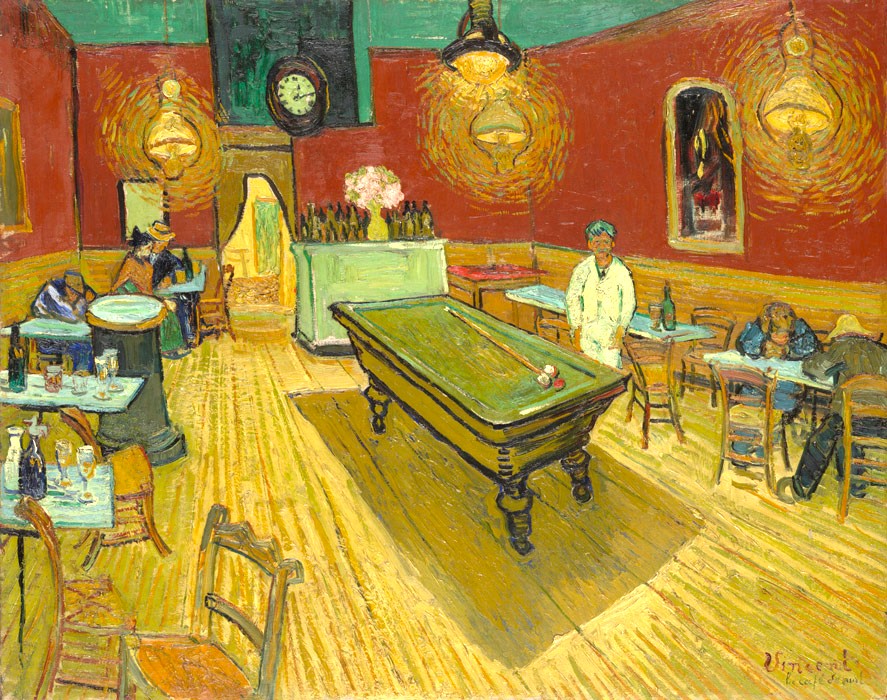

Indeed, compared to his Arles period—when he used bright complementary colors in works like The Night Café or Café Terrace at Night—his final paintings have a quieter palette.

Instead, his brushstrokes became more intense and swirling—full of power and life.

They reflect his overflowing passion.

He once wrote:

” I’d rather paint people’s eyes than cathedrals, for there’s something in the eyes that isn’t in the cathedral — although it’s solemn and although it’s impressive — to my mind the soul of a person, even if it’s a poor tramp or a girl from the streets, is more interesting. “ 39

No matter how his style evolved, painting was, for him, an act of expressing the soul.

Whether he painted people, trees, or landscapes, he was always seeking the invisible—the “spirit” within.

Color and brushwork were tools to communicate emotion.

That’s why he never followed trends or critics’ opinions.

He stayed true to his own sense of expression.

Although Van Gogh was almost unknown during his lifetime, the style he built in just ten years paved the way for later movements like Fauvism and Expressionism, opening a new chapter in modern art.

Collection of the Musée d’Orsay

A Life That Was Never Truly Lonely

Van Gogh is often remembered as an “unfortunate painter” who found fame only after death.

But his short life was shaped by the love and support of his family and friends.

Though his intense personality sometimes pushed people away, his brother Theo never abandoned him. Theo stayed by his side, emotionally and financially, until the very end.

In one of his last letters, written before leaving the hospital in Saint-Rémy, Vincent expressed his gratitude:

” yes – this journey is well and truly finished. Anyway, what consoles me is the great, the very great desire that I have to see you again, you, your wife and your child, and so many friends who have remembered me in my misfortune, as, for that matter, I don’t stop thinking of them either. ” 40

Despite his illness and struggles, Van Gogh spent his last years reflecting on his life and realizing what he had achieved as an artist.

His time in Saint-Rémy and Auvers may have been difficult, but there is a quiet sense of fulfillment in his final words and paintings.

From this letter, we can feel his peace—his sense that, at last, he was ready to rest.

Collection of the Národní galerie v Praze

Epilogue

With this, our “Van Gogh: A Closer Look ” series comes to an end.

When people hear the name Vincent van Gogh, they often imagine a “mad genius.”

But in truth, he was a deeply sensitive person who lived with constant inner struggles—very human ones.

Once you begin to see that side of him, the way you view his paintings may change completely.

To be honest, I wasn’t always a fan of Van Gogh’s bold, rough brushstrokes.

Yet, as I wrote this series, I found myself growing attached to his Cypresses.

Some say those cypress trees represent death or despair.

But during his time in Saint-Rémy, even as he faced illness, Van Gogh found hope through painting.

In those swirling strokes, I see not despair—but a strong will to live.

Which of his works left the deepest impression on you?

If this series has helped you feel a little closer to Van Gogh’s world, I couldn’t be happier.

Thank you so much for reading to the end!

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

Sources

- Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 772, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Thursday, 9 May 1889, in The Letters of Vincent van Gogh, ed. Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2009). ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 779. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let779/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 783. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let783/letter.html ↩︎

- Translated by the author from The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, vol. 6, translated by Shiro Futami, Misuzu Shobo, 1984, p.2042, Letter from Theo van Gogh to van Gogh, 4 October 1889. ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 822. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let822/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 779. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let779/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 797. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let797/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 800. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let800/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Willemien van Gogh, letter 785. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let785/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 800. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let800/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 800. ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 800. ↩︎

- Theo van Gogh to van Gogh, letter 819. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let819/letter.html ↩︎

- Isaacson, Joseph. “Letters from Paris.” De Portefeuille, 17 Aug. 1889. Via Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith., Van Gogh: The Life, Random House, 2011. https://vangoghbiography.com/. Accessed 5 Nov. 2025. ↩︎

- Albert Aurier, The Isolated Ones: Vincent van Gogh, Mercure de France, January, 1890, THE VINCENT VAN GOGH GALLERY. https://www.vggallery.com/misc/archives/aurier.htm. Accessed 5 Nov. 2025. ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Albert Aurier, letter 853. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let853/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 854. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let854/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Willemien van Gogh, letter 832. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let832/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Anna van Gogh-Carbentus, letter 831. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let831/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Willemien van Gogh, letter 856. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let856/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 863. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let863/letter.html ↩︎

- Theo van Gogh to van Gogh, letter 867. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let867/letter.html ↩︎

- John Rewald, Post-Impressionism from Van Gogh to Gauguin, p. 356, noted by Dr. Peyron in the asylum register. Via Naifeh and Smith (2011). Accessed 6 Nov. 2025. ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 870. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let870/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 870. ↩︎

- Translated by the author from Naifeh and Smith, Van Gogh: The Life. Translated by Kazuya Matsuda, vol. 2, Kokusho Kankokai, p.350 ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh and Jo van Gogh-Bonger, letter 873. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let873/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Willemien van Gogh, letter 879. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let879/letter.html ↩︎

- Theo van Gogh to van Gogh, letter 894. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let894/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 896. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let896/letter.html ↩︎

- Translated by the author from Shiro Futami, Detailed Biography of van Gogh (Tokyo: Misuzu Shobo, November 1, 2010), p.283. ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Willemien van Gogh, letter 879. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let879/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 902. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let902/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 902. ↩︎

- Adeline Ravoux, Memoirs of Vincent van Gogh’s stay in Auvers-sur-Oise, Via THE VINCENT VAN GOGH GALLERY. https://www.vggallery.com/misc/archives/a_ravoux.htm ↩︎

- Translated by the author from Naifeh and Smith, Van Gogh: The Life. Translated by Kazuya Matsuda, vol. 2, p.385. ↩︎

- Letter from Theo van Gogh to Anna van Gogh-Carbentus, 1 Aug. 1890. Via Naifeh and Smith. https://vangoghbiography.com/. Accessed 7 Nov. 2025. ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 777. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let777/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 549. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let549/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 865. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let865/letter.html ↩︎

Comments