Hello and welcome back to Art Ohenro!

In the previous chapter, we explored van Gogh’s early years as a painter and the works he created in his home country, the Netherlands.

This time, we’ll continue with the next chapter of his journey — the Arles Period!

(If you haven’t read the previous part yet, check it out here!)

What Was van Gogh’s “Arles Period”?

It was during his time in Arles, in southern France, that van Gogh developed his bright, colorful style.

Many of his most famous paintings — including Sunflowers and Café Terrace at Night — were created during this period.

In short, Arles was the golden era of van Gogh’s artistic life.

But before he arrived there, van Gogh spent time in Antwerp and Paris, where he met inspiring people and encountered new artistic ideas.

Who did he meet, and what moved him so deeply that it transformed his art forever?

Let’s find out together.

Moving to Antwerp

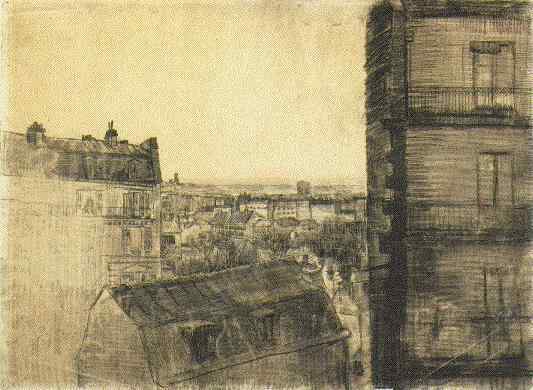

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

Antwerp, Belgium’s largest port city

In November 1885, at the age of 32, Vincent van Gogh left the rural Dutch village of Nuenen and moved to Antwerp, Belgium’s largest port city.

After years in the countryside, he was thrilled to experience city life again.

In his letters to his brother Theo, you can clearly sense his excitement:

“I can’t tell you how delighted I still am that I came to Antwerp. And how much there is to observe here for me, who has been out of things for so long.

How much good it does me — much as I love the peasants and countryside — to observe a city again.” 1

Life in the City and the Search for Models

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

In Antwerp, Van Gogh continued to focus on portrait painting, just as he had in the Netherlands.

But this time, he had a clever idea:

“I don’t consider it impossible that I might be able to come by some good models by painting portraits… Perhaps the idea of painting portraits and getting the sitters to pay for them by posing is a safer way.” 2

“My best chance is in figures… I feel a power to do something within me. I see that my work holds its own against other work” 3

His plan was to offer portraits as payment instead of cash.

However, things didn’t go as smoothly as he hoped.

Soon, Van Gogh began visiting brothels, paying dancers and prostitutes to pose for him.

Ironically, his “money-saving idea” ended up costing him even more.

Frustrated, Theo urged his brother to return to the countryside, but Van Gogh refused firmly:

“I don’t think that you can reasonably ask me to go back to the country for the sake of perhaps 50 francs a month less… Be fair enough to let me go on, because I tell you, I’m not looking for a row and I don’t want a row, but I won’t allow my career to be blocked.” 4

That stubbornness — the same trait that had once driven him away from Nuenen — was still there, stronger than ever.

The Royal Academy of Fine Arts

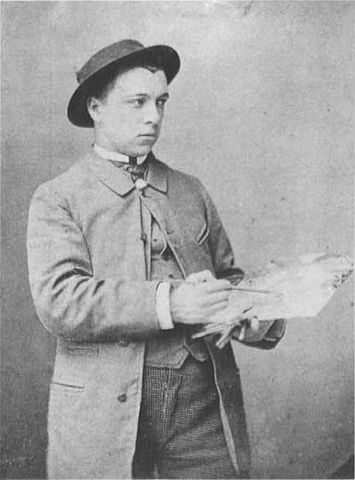

img: by Friedrich Tellberg

Van Gogh couldn’t accept Theo’s request to return to the countryside.

Determined to stay in Antwerp, he argued that he wanted to attend an art school — where he could use models at a low cost and meet new people.

Soon after, he enrolled in the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp.

He threw himself into his studies, using his strong drawing skills developed during the Dutch years.

When two wrestlers posed as models, Van Gogh captured them with incredible speed and energy.

But then—

The school’s principal, Charles Verlat, took one look at van Gogh’s drawing and reportedly said:

“I won’t fix this rotten dog of a drawing. Now, go back to the drawing class!”5

Clash in the Drawing Class

Although he’d just been called a “rotten dog,” Van Gogh followed instructions and went to the drawing class.

However, more trouble was waiting for him there.

One day, the students were asked to draw the Venus de Milo.

Van Gogh’s version, however, featured an unusually large waist and hips.

When the teacher, Eugène Siberdt, corrected it with his crayon, van Gogh lost his temper and shouted:

“That’s exactly why you don’t understand what a young woman really is! A woman must have hips, thighs, and a womb to carry children!” 6

This bold remark shocked everyone at the academy.

Siberdt focused on perfect lines and shapes — a precise academic drawing style.

But Van Gogh rejected that approach, insisting that such drawings lacked “life.”

After this incident, Van Gogh stopped attending classes altogether.

It wasn’t the first time.

Back when he trained to become a preacher, he also quit his theological school halfway through.

Clearly, Van Gogh’s stubborn and passionate nature didn’t fit well with structured institutions.

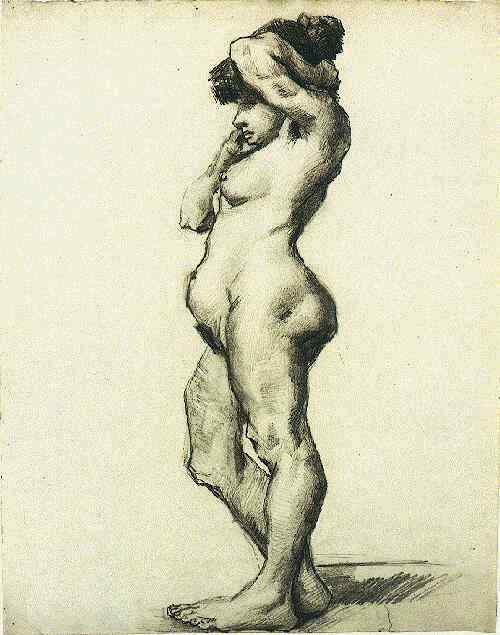

The “Large-Hipped Venus”

One of van Gogh’s classmates, Victor Hageman, later recalled the event with a mix of humor and awe:

“The beautiful Greek goddess had turned into a strong Flemish housewife…

I can still picture her—this short, heavy Venus with enormous hips, born from van Gogh’s charcoal.” 7

Since nude studies of women were forbidden at the Academy, this drawing was likely made at a private “sketch club” formed by students outside the school.

Illness and Possible Syphilis

Around the time Van Gogh began visiting brothels in Antwerp, his health started to decline rapidly.

In a letter to Theo, he described his condition in alarming detail:

“I have no fewer than 10 teeth that I’ve either lost or am losing. And that’s too many and too disagreeable, and besides it makes me look as though I’m over 40…

I was told at the same time that I ought to look after my stomach…

It was the last month that I’ve had a lot of trouble with it — I also started to cough all the time, bring up phlegm &c., so that I became worried.” 8

Van Gogh’s body was clearly in terrible shape — his teeth were falling out, his stomach hurt, and he was constantly coughing.

Heavy smoking and poor nutrition likely played a role, but that alone couldn’t explain everything.

It’s known that Van Gogh had visited brothels since his younger days.

During his time in The Hague, while living with Sien, he was even hospitalized with gonorrhea.

Given this history, many researchers believe Van Gogh may have contracted syphilis.

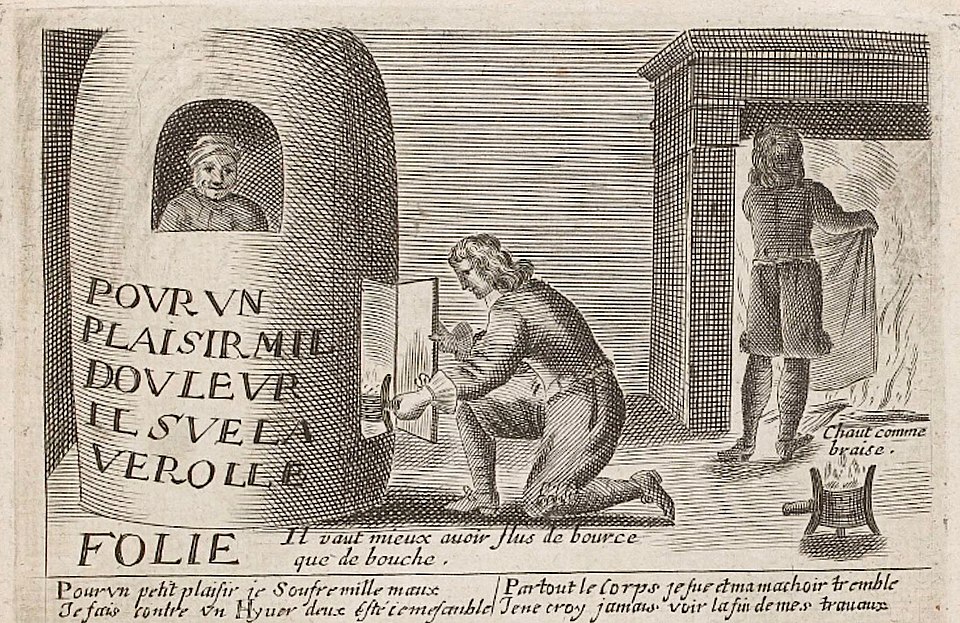

Syphilis and Its “Terrifying Treatment”

At that time, the common treatment for syphilis involved mercury — not only taken orally, but also applied to the skin as an ointment or inhaled as vapor.

One particularly shocking belief of the day was that mercury poisoning symptoms — such as excessive drooling — were seen as “proof” that the disease was leaving the body.

From a modern point of view, this was completely the opposite of true healing.

Today we know that mercury causes severe damage: it leads to gum disease, tooth loss, and serious harm to the brain and internal organs.

It was an extremely dangerous treatment that would never be used in modern medicine.

Signs of Mercury Poisoning?

Van Gogh’s descriptions — tooth loss, grayish phlegm, and sudden physical weakness — all match the known symptoms of mercury poisoning.

It’s very possible that he underwent mercury treatment for syphilis, meaning he was suffering not only from the illness itself but also from its toxic “cure.”

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

Escape from Antwerp

As his health declined and his time at the art academy ended in frustration, Van Gogh’s dreams in Antwerp began to crumble.

He felt cornered, anxious, and unable to make the progress he had hoped for.

In a letter to Theo, he confessed:

“It’s true, for instance, that wanting to progress too quickly here, I may actually have progressed less, but what would you? My health is also behind it” 9

The mood was similar to the hopelessness he once felt in Drenthe.

This time, however, Van Gogh decided to escape the situation entirely — he planned to move to Paris and live with his brother Theo.

But Theo refused. He urged Vincent to return to Nuenen and rest instead.

Yet once Van Gogh had made up his mind, there was no turning back.

“But where the issue is — to take better care of oneself — well in Brabant I’d wear myself out again taking models, the same old story would start all over again, and it doesn’t seem to me that any good could come of it. That way — we’d be straying from the path. So please give me permission to come sooner if need be. In fact I’d say right away, if need be.” 10

Vincent argued that living together would save them both money on rent and food. But Theo’s concern lay much deeper than finances.

He couldn’t help but recall his brother’s past troubles in Nuenen — the scandal with Margot, the falling-out with his gentle friend Rappard, and even his expulsion from the family home. It was clear that Vincent’s presence could easily stir up more problems in Paris.

Theo loved his brother, but as the manager of Goupil’s Paris branch, the last thing he wanted was to be dragged into another of Vincent’s misfortunes. He had his own position to protect — and getting entangled in his brother’s chaos was, quite frankly, the last thing he needed.

He tried to persuade Vincent to stay put and recover for a while longer. But just when Theo thought the matter had been settled, a letter arrived in familiar handwriting:

“Don’t be cross with me that I’ve come all of a sudden… Will be at the Louvre from midday…

So get there as soon as possible.” 11

Yes — before Theo could give his permission, Vincent had already arrived in Paris.

In Paris

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

Life with Theo Begins

In March 1886, at the age of 32, Vincent van Gogh suddenly showed up in Paris and began living with his brother Theo.

Theo gave up his old apartment in Montmartre and moved to a larger one on Rue Lepic so that Vincent could have a studio space.

At first, things went relatively smoothly. But before long, Vincent’s life in Paris became chaotic. Paints and brushes were scattered everywhere, turning the entire apartment into what one visitor described as “more like a paint shop than a home.”

“The place was in complete disorder. He seemed to prefer living in a mess.” 12

“One morning, as I stepped out of bed, I accidentally put my foot into one of Vincent’s paint pots.” 13

Soon, the maid fled, unable to stand the chaos. Theo, already in poor health, fell ill for unknown reasons. Vincent even started arguing with guests who came to visit.

Theo had expected that living with his brother would be difficult—but not this difficult. Reaching his breaking point, he confessed in a letter to their sister:

“It’s impossible to live with him… because he spares nothing and no one.”14

“Everyone who meets him says the same thing: ‘He’s insane.’” 15

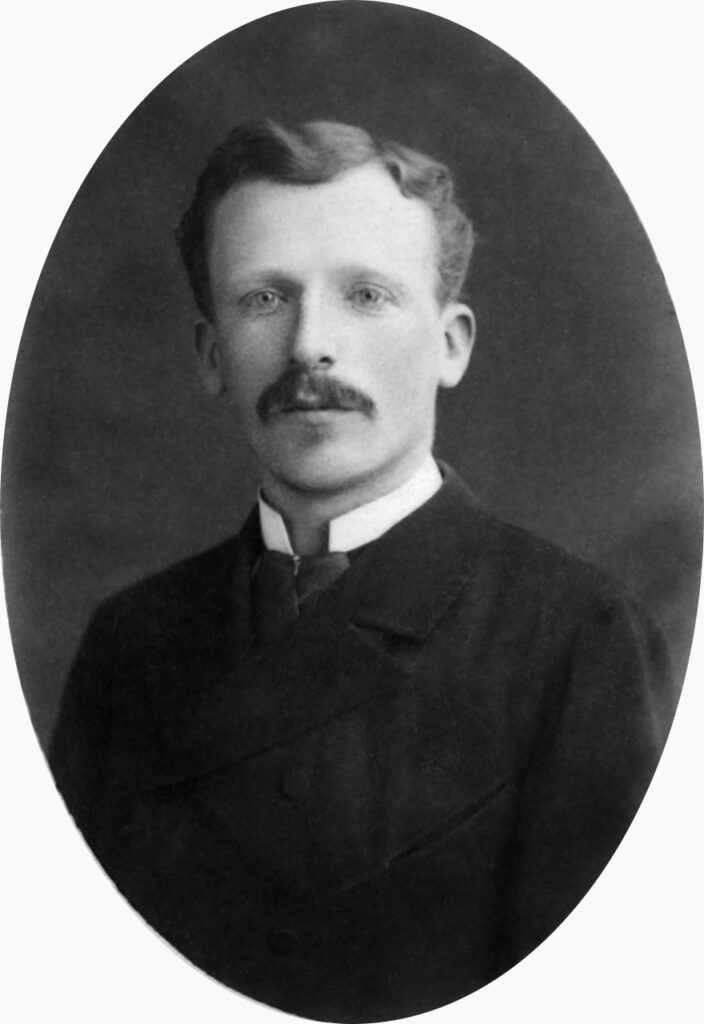

The Cormon Studio

Once settled in Paris, Van Gogh began studying at the studio of Fernand Cormon, thanks to Theo’s introduction.

Although Cormon was known for his academic style, he was surprisingly open-minded as a teacher and did not force his students to follow his own methods.

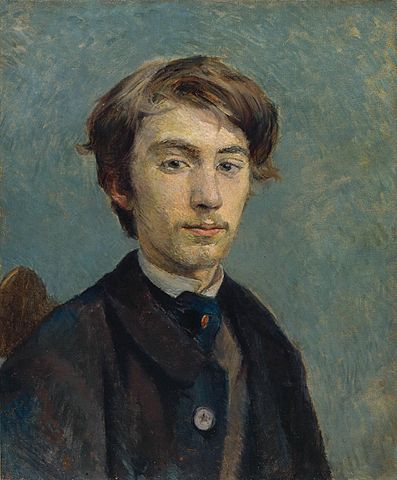

At that time, Cormon’s studio attracted many young talents who would later become famous—Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Émile Bernard, Louis Anquetin, and John Peter Russell, among others.

Cormon demonstrates before his students; Lautrec is seen in the foreground, with his back to the viewer.

But once again, Van Gogh failed to fit in. Just like at the art academy in Antwerp, he struggled to connect with his classmates and gradually became isolated.

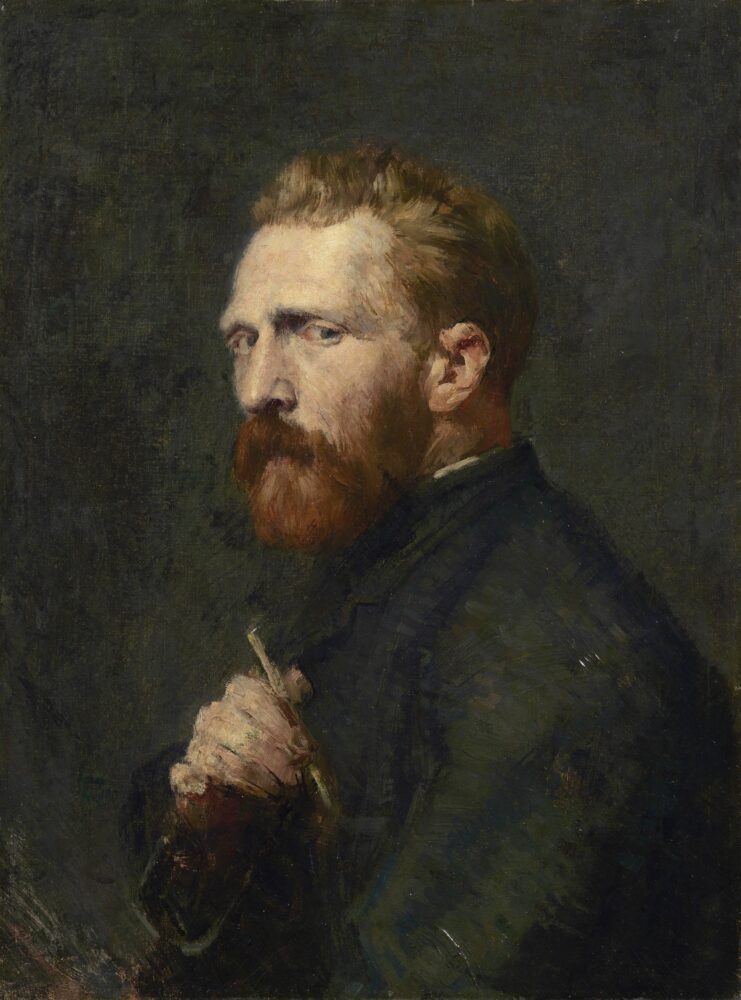

There was, however, one exception—John Peter Russell, a painter from Australia. Vincent often visited Russell’s studio, and the two became close friends. During this time, Russell painted a striking portrait of Van Gogh.

Russell painted Vincent with slightly fuller cheeks—perhaps a friendly bit of idealization.

Vincent cherished the portrait deeply and kept it with him for the rest of his life. Yet, aside from Russell, he couldn’t form any close friendships.

Within just three or four months, he decided to leave Cormon’s studio.

Later, in a letter to his acquaintance Horace Mann Livens, he reflected on the experience:

“I have been in Cormons studio for three or four months but did not find that as useful as I had expected it to be. It may be my fault however, any how I left there too as I left Antwerp and since I worked alone, and fancy that since I feel my own self more.” 16

Van Gogh and Monticelli — The Search for Color and Emotion

In May 1886, the 8th Impressionist Exhibition opened in Paris.

The star of the show was Georges Seurat’s masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

Using a new method called Divisionism (painting with tiny dots of color), Seurat based his technique on the science of optics and color theory.

This “scientific painting” shocked the Paris art world with its bold and innovative approach.

Soon, Seurat and his followers became known as the Neo-Impressionists, and art in Paris began moving toward theory and precision.

But what about Van Gogh?

He was aware of this new movement, and in a letter to his friend Livens, he wrote:

“I have much admired certain Impressionist pictures” 17

However, the only names he mentioned were Degas’s nudes and Monet’s landscapes.

He did not say a single word about Seurat.

In the same letter, he also wrote:

“since I saw the Impressionists I assure you that neither your colour nor mine as it is developping itself, is exactly the same as their theories” 18

In other words, Van Gogh seemed to feel a certain distance from the Impressionists—especially from the Neo-Impressionists, whose approach analyzed and divided color in a logical way.

He believed in a more intuitive and emotional use of color, inspired by Eugène Delacroix.

Among Delacroix’s artistic heirs, one painter captured Van Gogh’s imagination more than anyone else—Adolphe Monticelli.

Monticelli’s works were full of thick paint, rich tones, and overflowing emotion.

The colors seemed to rise from the canvas itself, and van Gogh was deeply drawn to that expressive power.

When Monticelli passed away in June 1886, Van Gogh saw him as a “hero of color.”

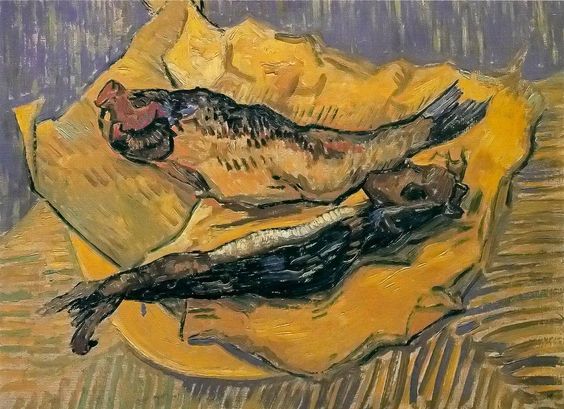

He began painting still lifes in Monticelli’s style, trying to capture that same passionate intensity.

For Van Gogh, who didn’t fully belong to Impressionism or Neo-Impressionism, Monticelli became a guiding light in his search for his own vision of color.

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

Collection of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Light, Landscape, and the Signs of Change

After leaving the Cormon studio, van Gogh shut himself away in his room and painted tirelessly.

But reality was harsh—none of his works sold.

His frustration grew, and it began to spill over onto his brother Theo.

Theo’s friend Andries Bonger later recalled:

“He would blame Theo for everything, even for things that were not his fault.” 19

The atmosphere at home was stormy.

Exhausted by the endless tension, Theo finally confessed his feelings in a letter to their younger sister Willemien in March 1887:

“There was a time when I loved Vincent, and when he was my best friend…

But those days are gone now. I want him to leave and stand on his own, and I’ll do everything I can to make that happen.” 20

Around this time, Van Gogh sensed that Theo was reaching his limit.

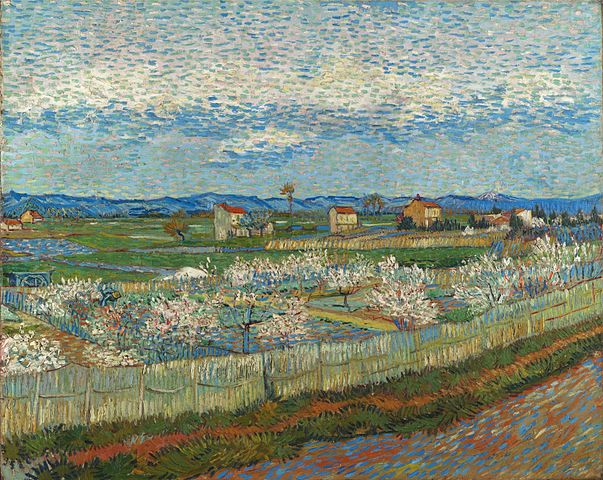

Perhaps to ease the tension—or perhaps to rediscover himself—he began stepping outside again to paint landscapes under natural light.

At first, it might have been just to calm his brother.

But once he experienced the bright light of Paris, his art began to change completely.

Brighter Colors and the Study of Impressionism

In Paris, Van Gogh began to focus deeply on landscapes—views along the Seine River, the streets of Paris, and the nature around the suburbs.

Unlike before, when landscapes were just a background for his figure paintings, you can now see that he was truly pouring his heart into the scenery itself.

Building on the color theories of Charles Blanc, Eugène Delacroix, and Adolphe Monticelli that he had studied, Van Gogh now began to explore plein air painting for the first time.

By painting outdoors, his colors became brighter and more vibrant.

He also experimented with the broken brushstrokes used by the Impressionists, and eventually adopted techniques from Neo-Impressionism—placing small touches of color side by side to create shimmering effects of light.

Through this process, we can see Van Gogh’s constant search for his own unique style.

These experiments with Impressionist color and brushwork would later grow into the signature style that defines his most famous works.

The Encounter with Japanese Woodblock Prints — A Door to Color

To sustain his life in Paris—and to mend his strained relationship with his brother Theo—Van Gogh devoted himself completely to painting landscapes.

Thanks to his effort, peace slowly returned between the brothers.

Theo wrote to their sister Wilhelmina:

“We’ve made up. I hope things will keep going well… Vincent is working hard and improving. His paintings are getting brighter—he’s trying to capture sunlight.” 21

Around this time, the Goupil & Cie gallery, where Theo worked, began shifting its focus toward Impressionist art.

Theo was put in charge of discovering new talent.

He organized an exhibition of twelve works by Claude Monet in the mezzanine of the Paris branch, which gained attention and boosted his reputation as an art dealer.

Soon, ambitious young painters hoping to be discovered started showing up at Theo’s door—one of them was Émile Bernard.

At first, Bernard befriended Van Gogh mainly to attract Theo’s interest (most artists found Vincent too difficult to approach).

But that calculated connection gradually turned into a genuine and inspiring friendship.

Collection: The National Gallery, London

Bernard was only eighteen at the time, but already fiercely ambitious about art.

He believed that “the future of painting lies in simple color planes and bold outlines.”

And as inspiration for this new direction in modern painting, Bernard pointed to Japanese woodblock prints (ukiyo-e).

Van Gogh was instantly fascinated.

He had already shown interest in Japanese art during his time in Antwerp, but now he began to study it seriously—as a true artistic model.

He visited the shop of Siegfried Bing, a dealer in Asian art, and bought several prints.

By copying and analyzing them, he discovered a new way to see and compose pictures:

instead of creating traditional Western depth, he focused on flat color areas, treating shapes as vivid “surfaces.”

This approach made his colors more distinct, added rhythm to the composition, and gave his paintings clarity and decorative beauty through strong outlines.

The light of Paris and the color of Japan—

When these two influences came together in van Gogh’s mind, it was like a spark igniting.

His sense of color evolved rapidly, bursting into the brilliant palette we recognize today.

Leaving Paris

In February 1888, Vincent van Gogh left Paris at the age of 34.

By this time, his relationship with Theo had calmed down considerably—no longer filled with the fierce arguments that once defined their life together.

Even so, Vincent decided to end their cohabitation and set off for the South of France.

The true reason for his departure remains unclear, but one widely accepted theory is that he left out of concern for Theo’s health.

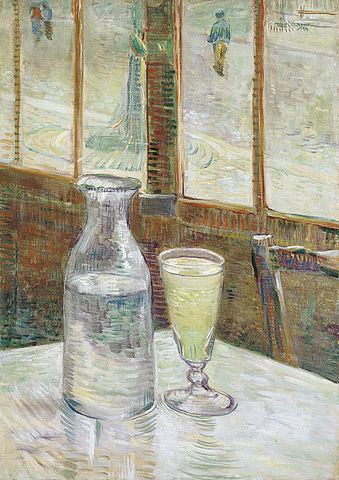

Vincent was living a rough, alcohol-soaked life—drinking absinthe, wine, beer, and cognac almost daily, and visiting brothels frequently. Instead of stopping him, Theo was being pulled into the same unhealthy routine.

Theo had always been physically fragile, and his health was declining further under stress. The previous year, he had even been rejected by Johanna Bonger, leaving him emotionally and physically drained.

Vincent saw all this up close.

He may have felt that his own presence was only making things worse for Theo.

So perhaps, by leaving Paris, Van Gogh was choosing distance—for Theo’s sake as much as his own.

Absinthe, an herbal liqueur, was inexpensive and widely consumed at the time, leading to many cases of addiction. Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec were both known to drink it often.

To Arles

Van Gogh attended one during his stay.

img: by Rolf Süssbrich

Finding “Japan” in the South of France

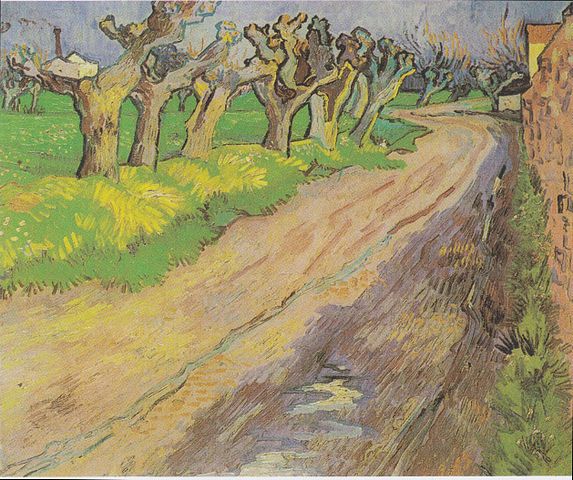

In 1888, Van Gogh moved to Arles, a small town in southern France.

Why he chose this place is still uncertain, but his letters to Theo and Émile Bernard offer clues.

“the landscape under the snow with the white peaks against a sky as bright as the snow was just like the winter landscapes the Japanese did.” 22

“But, my dear brother — you know, I feel I’m in Japan.” 23

“this part of the world seems to me as beautiful as Japan for the clearness of the atmosphere and the gay colour effects. The stretches of water make patches of a beautiful emerald and a rich blue in the landscapes, as we see it in the Japanese prints.“ 24

To Van Gogh, the bright light and colors of Arles looked exactly like the Japan he had always dreamed of.

The world of ukiyo-e woodblock prints—the art he had admired for years—seemed to come alive before his eyes in the southern sunlight.

In that sense, Arles was his “Japan within Europe.”

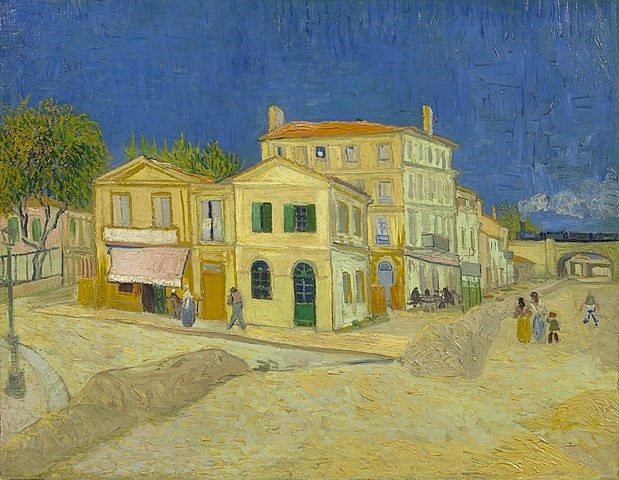

The Yellow House — A Dream Atelier in the South

After a few months in Arles, van Gogh first lived in a small room at the Carrel Restaurant.

But after disagreements over rent, he decided to move. The next place he chose was a bright building with yellow walls—the Yellow House.

Inside, however, it was far from comfortable: no electricity, no gas, and even the toilet was in a neighboring inn.

Still, Vincent fell completely in love with it.

“It’s painted yellow outside, whitewashed inside — in the full sunshine… right out in the sun, at last I’ll see my canvases in a really bright interior.” 25

“Inside, I can live and breathe, and think and paint. And it seems to me that I should go further into the south rather than going back up north, because I have too great a need of the strong heat so that my blood circulates normally. I’m in really much better health here than in Paris.” 26

The actual Yellow House was destroyed during World War II bombings.

“I’d like to be able to create a pied-à-terre which, when people were exhausted, could be used to provide a rest in the country for poor Paris cab-horses like yourself and several of our friends, the poor Impressionists.“ 27

For van Gogh, the Yellow House was not just a place to live—it was the foundation of a dream community for artists.

He imagined a shared atelier where struggling painters, not the successful ones of the Paris boulevards, could create freely together.

Theo, who supported avant-garde artists through his work as a dealer, found the idea appealing as well.

Vincent passionately wrote to him about the plan, hoping for his help in making it real.

But behind this artistic dream lay something more personal—a longing to fill his loneliness.

Alone again after leaving Paris, Van Gogh often thought back to the days in Etten, when he painted and laughed with his friend Anthon van Rappard.

He dreamed of recreating that time—of living and working side by side with another artist once more.

“If necessary, I could live at the new studio with someone else, and I’d very much like to.” 28

The Colors of the Night

During his time in Arles, Van Gogh created many paintings — some of them capturing the magic of the night.

To paint these night scenes, he often went outside even at night, drawing vivid colors out of the darkness.

“It often seems to me that the night is even more richly coloured than the day, coloured in the most intense violets, blues and greens…

I enormously enjoy painting on the spot at night. In the past they used to draw, and paint the picture from the drawing in the daytime. But I find that it suits me to paint the thing straightaway.” 29

Collection of the Musée d’Orsay

Another masterpiece, Café Terrace at Night, was also painted during this period.

Van Gogh closely observed the light of the night and captured its subtle color shifts on his canvas.

“I was interrupted precisely by the work that a new painting of the outside of a café in the evening has been giving me these past few days…

Now there’s a painting of night without black. With nothing but beautiful blue, violet and green, and in these surroundings the lighted square is coloured pale sulphur, lemon green…” 30

Collection of the Kröller-Müller Museum

Van Gogh tried to bring out the hidden colors of darkness and use them to express emotion.

By emphasizing the way colors change, he sought to make viewers feel the intensity of the scene.

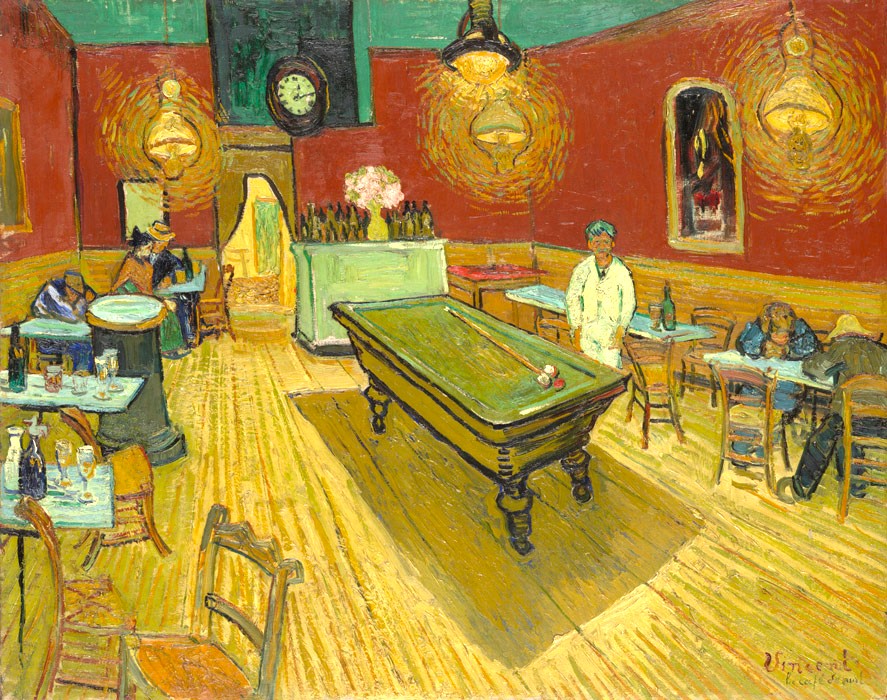

One striking example of this approach is “The Night Café“, painted in the same month, September 1888.

The setting was the Café de la Gare, a place where he stayed before moving into the Yellow House.

It was open all night and often filled with people who had nowhere else to go.

To capture its tense and uneasy atmosphere, Van Gogh reportedly stayed up for three nights painting.

“In my painting of the night café I’ve tried to express the idea that the café is a place where you can ruin yourself, go mad, commit crimes. Anyway, I tried with contrasts of delicate pink and blood-red and wine-red. Soft Louis XV and Veronese green contrasting with yellow greens and hard blue greens.

All of that in an ambience of a hellish furnace, in pale sulphur.

To express something of the power of the dark corners of a grog-shop.” 31

Collection of the Yale University Art Gallery

Using the complementary colors of red and green, Van Gogh revealed “the terrible passions of humanity.”

This attempt to portray anxiety and madness through color would later inspire Fauvism and Expressionism.

Unlike the Impressionists, who focused on the natural light of the world, Van Gogh sought something deeper.

He wasn’t painting what the eye sees — he was painting what the soul feels.

“I’d rather paint people’s eyes than cathedrals, for there’s something in the eyes that isn’t in the cathedral — although it’s solemn and although it’s impressive — to my mind the soul of a person, even if it’s a poor tramp or a girl from the streets, is more interesting.“ 32

Even before he became a painter, Van Gogh cared deeply about people.

Whether he was preaching in a mining village or painting peasants and laborers, his attention was always on the human spirit.

In Arles, this perspective evolved into a unique style — one that could express “the soul of humanity” even through landscapes and still lifes.

Life Together in the “Yellow House”

Gauguin and the Sunflowers

When Van Gogh heard that his old friend Paul Gauguin was struggling financially, he proposed a plan to his brother Theo.

The idea was simple but bold: Gauguin would live with him in the Yellow House in Arles, while Theo would send 250 francs per month to support their living expenses.

In return, Gauguin — who was more famous than Van Gogh at the time — would send Theo at least one painting each month.

It seemed like the perfect arrangement for everyone.

Gauguin could focus on painting without worrying about money, Theo would receive new works to sell, and Vincent would finally have a companion to ease his loneliness.

While waiting for Gauguin’s arrival, van Gogh eagerly prepared the Yellow House.

Using the extra money Theo sent, he bought furniture and began creating paintings to decorate the rooms.

The centerpiece of this decoration would become his most iconic subject — the sunflower.

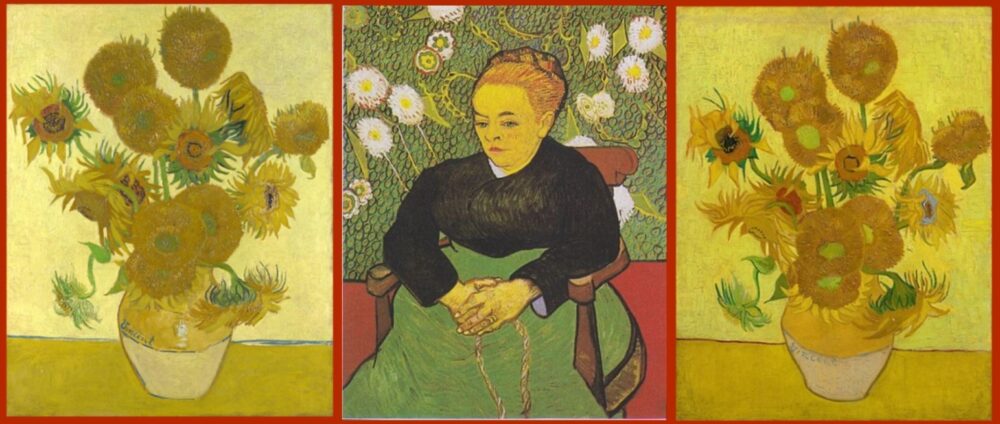

When Van Gogh and Gauguin first met in Paris in December 1887, they exchanged paintings as a gesture of friendship.

Gauguin gave Van Gogh a work from his time in Martinique, while Van Gogh offered two Sunflower paintings from his Paris period — now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Kunstmuseum Bern.

Gauguin loved Van Gogh’s Sunflowers so much that he hung them in his own studio (though he later sold them to fund a trip to Panama).

Remembering this, Van Gogh thought the Yellow House should be filled with the warmth of sunflowers.

Collection of the Metropolitan Museum

Collection of the Kunstmuseum Bern

In August 1888, before Gauguin arrived in Arles, van Gogh painted four new Sunflower canvases as decorations for his friend’s room.

Later, during their brief time living together, Van Gogh created three more versions based on those first paintings — even continuing the series in winter, when real flowers were no longer available.

Why did he paint so many?

The answer appears in one of his letters to Theo:

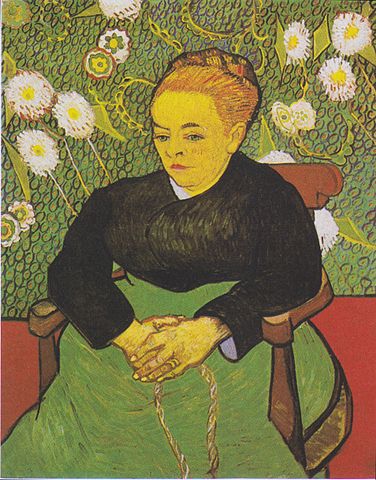

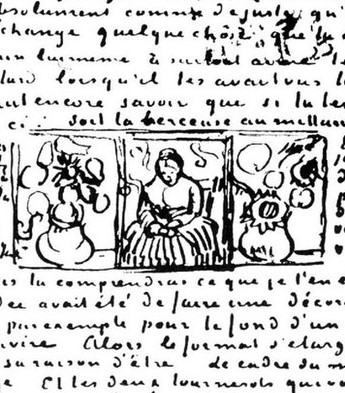

“the Berceuse in the middle and the two canvases of the sunflowers to the right and the left, this forms a sort of triptych. And then the yellow and orange tones of the head take on more brilliance through the proximity of the yellow shutters.” 33

In his letter sketch, Vincent placed La Berceuse in the middle, flanked by two Sunflowers — almost like an altar piece.

Since he painted several versions of La Berceuse, it’s possible he imagined displaying them all in similar triptych arrangements.

One of the sunflower replicas, it seems, was also meant as a gift.

After leaving Arles, Gauguin asked Van Gogh if they could exchange the Sunflowers for one of his own studies left in the Yellow House.

Van Gogh refused at first, still hurt by Gauguin’s sudden departure.

Yet his feelings softened, knowing how deeply Gauguin loved the work.

“Gauguin would be pleased to have one of them, and I very much enjoy doing Gauguin quite a big favour. So, he wants one of those two canvases, well I’ll do one of them over again, the one he wants.” 34

Thus, one of the most famous Sunflowers was painted for Gauguin.

Whether he actually received it remains uncertain — Vincent soon suffered another breakdown and was hospitalized shortly after completing it.

The Beginning of Their Shared Life

On October 23, 1888, Paul Gauguin finally arrived at the Yellow House in Arles.

For Vincent van Gogh, it was the start of a dream come true — the beginning of their artistic community.

But for Gauguin, things were different.

Although he had agreed to the plan, he had delayed his departure many times, citing poor health.

In truth, he was nervous about living with Van Gogh, whose mood swings and intensity were well known among the Paris art circle.

Even so, Gauguin decided to go — partly for practical reasons.

By living in Arles, he could save money and strengthen his connection with Theo, a respected art dealer.

In a letter to his friend Émile Schuffenecker, Gauguin wrote:

“At the end of this month, I’ll leave for Arles. The purpose of this stay is to work in peace, without worrying about money. I expect to live there for quite some time, at least until I can reestablish myself in the art world.” 35

Van Gogh dreamed of making the Yellow House a kind of “refuge for artists.”

He imagined fellow painters gathering there to share ideas, inspire one another, and live together while supporting each other through art.

Gauguin, however, saw the stay as a temporary base — a stepping stone toward future success.

And indeed, his pragmatic view soon proved right.

Just a few days after he arrived in Arles, Theo began to sell Gauguin’s paintings in Paris — five works sold within two months.

Gauguin’s success was good news for Theo as an art dealer — and it should have been cause for joy for Vincent, too, both as a brother and as a friend.

But deep down, Van Gogh couldn’t hide his frustration.

“I can do nothing about it if my paintings don’t sell... I believe that the day will come when I’ll sell too, but I’m so far behind with you, and while I spend I bring nothing in.

That feeling sometimes makes me sad.” 36

Gauguin had begun his career as a painter in his thirties, and his rapid rise brought van Gogh not only admiration but also a growing sense of anxiety and self-doubt.

Conflict

After moving into the Yellow House, Vincent van Gogh began painting alongside Gauguin.

They often painted the same subjects—like the “vineyards” or the local café owner, Madame Ginoux—and showed their works to each other for feedback.

But behind those seemingly peaceful days, cracks slowly began to appear between them.

Their ideas about art were completely different.

Gauguin believed in Synthetism, rejecting the Impressionist idea of painting what one sees directly.

He wanted to paint from the imagination—to express what was inside the mind rather than what appeared before the eyes.

To him, Van Gogh’s habit of painting everything spontaneously and on the spot seemed completely “nonsensical.”

He advised Van Gogh to paint more from imagination.

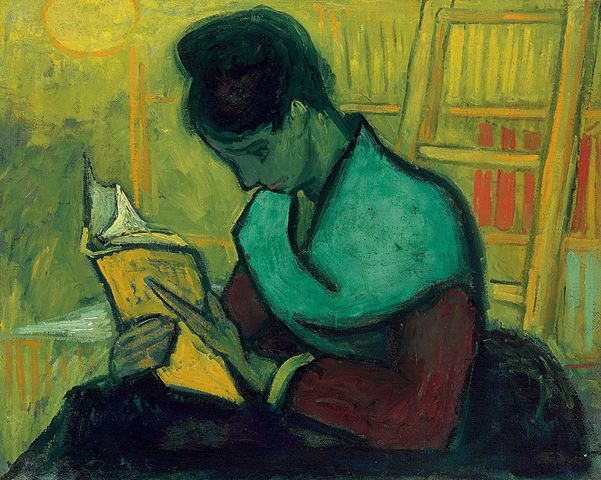

In response, Van Gogh tried works such as Memory of the Garden at Etten and The Novel Reader, both painted from memory rather than direct observation.

But he quickly realized this approach didn’t suit him.

“I’ve spoiled that thing I did of the garden at Nuenen (i.e.,Memory of the Garden at Etten)“ 37

Hermitage Museum

Private Collection

At the same time, Van Gogh often criticized Gauguin’s paintings in detail and pushed his own opinions too strongly.

Gauguin, growing frustrated, wrote to their mutual friend Émile Bernard:

“Vincent and I rarely agree—especially when it comes to painting.” 38

The tension soon extended beyond art.

Their daily life together became increasingly strained.

The studio was always messy, and Van Gogh was poor at managing money.

Having once worked as a sailor and stockbroker, Gauguin was used to a more orderly lifestyle.

He took care of cooking and bookkeeping, trying to support Vincent, who lacked such practical skills.

But even when Gauguin taught him how to cook, Vincent’s meals were, as Gauguin put it, “almost impossible to eat.”

In the end, shopping was about the only household chore Van Gogh could manage.

Van Gogh deeply respected Gauguin—as both an artist and a person.

But his own sense of failure, their constant disagreements, and Gauguin’s control over their shared life slowly agitated him.

His frustration turned into outbursts—this time directed at Gauguin.

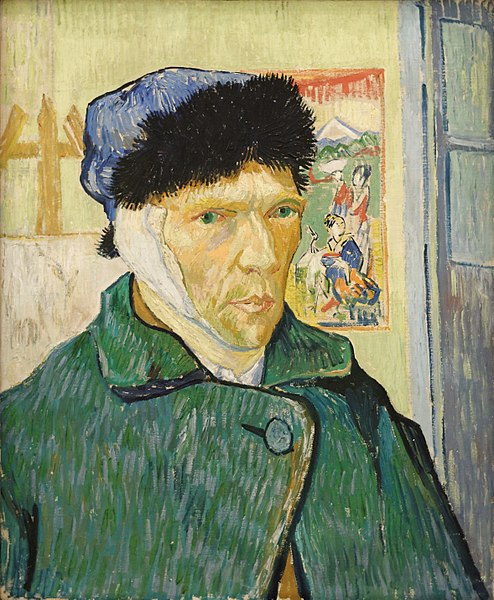

The Ear Incident

Break with Gauguin and Theo’s Marriage

As the tension grew, Gauguin began to feel he could no longer live with Van Gogh.

He even moved his easel into the kitchen to keep distance, but he still had to pass through Vincent’s bedroom to reach his own.

Finally, Gauguin wrote to Theo:

“Please send part of the payment from my sold paintings. Once the accounts are settled, I must return to Paris.

Vincent and I are too different in temperament to live together without constant quarrels.

We both need peace to work.” 39

Vincent probably never heard Gauguin say “I’m leaving” directly—but he sensed it clearly.

“I myself think that Gauguin had become a little disheartened by the good town of Arles, by the little yellow house where we work, and above all by me.” 40

Around the same time, another piece of news reached him—Theo was getting married to Johanna Bonger, the sister of his friend Andries.

As an older brother, Vincent truly wished him happiness.

Yet deep down, he couldn’t help feeling uneasy.

He had secretly hoped that someday Theo might leave Paris and live with him in Arles.

Now, with Theo’s heart turning toward his new wife, Vincent feared he might be abandoned.

Theo had no such intention, of course—but Vincent’s mind sank deeper into doubt and loneliness.

Over the years, everyone Van Gogh cared for—Rappard, Tersteeg, Sien, and even his father—had drifted away from him.

Until now, he always thought, They didn’t understand me, or The environment was wrong.

But during this painful separation from Gauguin, he began to wonder:

Maybe the problem lies within me.

And now, even Theo—the one person who had always stood by him—seemed to be slipping away.

The fear of being abandoned by Theo, mixed with guilt for not being able to fully celebrate his brother’s happiness, tore Vincent apart.

These conflicting emotions quietly pushed him toward the edge—setting the stage for one of the most tragic moments in art history.

The Tragedy Before Christmas

On the night of December 23, 1888, the rain that had long soaked the town of Arles finally stopped.

Gauguin went out alone — perhaps to a café, perhaps to a brothel.

Maybe he simply wanted to get away from the Yellow House, even for a short while.

As he walked, he suddenly felt someone behind him.

Turning around, he saw Van Gogh.

Sensing something strange in Vincent’s recent behavior, Gauguin tensed up and spoke to him.

Van Gogh quietly asked:

“Are you leaving?”

Caught off guard, Gauguin hesitated for a moment before answering,

“…Yes.”

Then Van Gogh took a newspaper clipping from his pocket and handed it to him in silence.

The headline read: “Murderer on the Run.”

Without another word, Van Gogh turned away and disappeared into the darkness.

Uneasy and alarmed, Gauguin decided not to return to the Yellow House that night.

The Ear and the Message

Back at home, Van Gogh fell into a manic frenzy.

In that state, he cut off his own left ear with a razor.

Bleeding heavily, he wrapped the ear in newspaper and set out toward a familiar place —

the brothel that both he and Gauguin often visited.

He handed the small package to a guard at the entrance, asking that it be delivered to Rachel, Gauguin’s favorite woman there.

But it wasn’t truly meant for her.

The message — desperate and wordless — was clearly meant for Gauguin himself.

Vincent probably believed, “He’s here tonight.”

When giving the package, Van Gogh said just one thing:

“Remember me.”

It was not anger, not a threat —

but a painful message carved from his own body,

a final attempt to reach his friend.

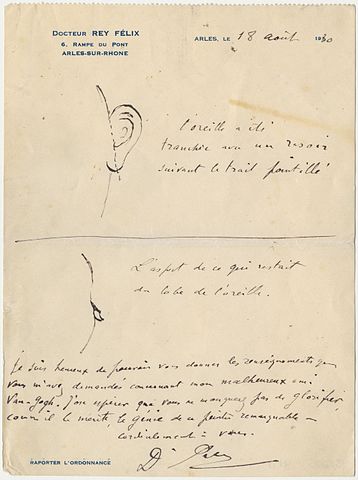

For years, people believed Van Gogh had only cut off part of his earlobe.

But the drawing in Dr. Rey’s letter to writer Irving Stone reveals that he had, in fact, removed almost the entire ear — leaving only a small piece of the lobe.

After the Incident: Days in the Hospital

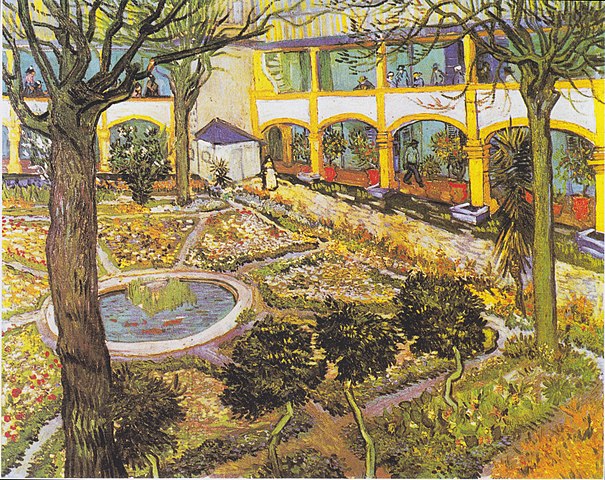

Arles Hospital

Oskar Reinhart Collection

On the morning of December 24, 1888, Vincent van Gogh was found unconscious in his bed at the Yellow House and taken to the hospital in Arles.

After receiving treatment for his ear, he slowly regained consciousness.

However, his mental condition remained unstable. He suffered from delirium and repeated confused speech and behavior.

On December 25, Theo rushed to Arles after receiving a telegram from Gauguin.

He visited his brother in the hospital and later described the meeting in a letter to his wife, Johanna:

“There were moments when he seemed slightly better, but soon he began talking again about theology and philosophy. It was heartbreaking to witness. At times he realized he was ill and wanted to cry, but he couldn’t.” 41

Before returning to Paris with Gauguin that same day, Theo asked Joseph Roulin, the local postman, and Pastor Frédéric Salles to keep an eye on Vincent and report on his condition.

Collection of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Roulin, who lived near the Yellow House, was one of van Gogh’s few close friends.

According to him, Vincent sometimes suffered from “terrible fits” and was once kept in solitary confinement.

Fortunately, his condition gradually improved, and by December 29, he was allowed to return to a shared ward.

At the start of the new year, Vincent wrote to Theo:

“Now I ask just one thing of you, not to worry, for that would cause me one worry too many.” 42

“I expect to start work again soon.” 43

Dr. Félix Rey, his attending physician, also added in the same letter:

“I am happy to tell you that my predictions have been borne out, and that this over-excitement was only fleeting. I strongly believe that he will have recovered in a few days’ time.”44

On January 7, Van Gogh was discharged and returned to the Yellow House.

That month, he painted masterpieces such as Van Gogh’s Chair and Gauguin’s Armchair, along with two new sunflower versions.

He also created and gifted a portrait of Dr. Rey, to whom he was deeply grateful.

In early February, Vincent’s condition worsened again.

At first, he thought he was fine—but gradually, he began to realize something was wrong.

He started to believe that someone was poisoning him.

On February 7, a neighbor, alarmed by his behavior, called the police.

Van Gogh was taken back to the hospital in Arles.

Fear and the Third Hospital Stay

By February 17, 1889, his condition had stabilized enough for a temporary discharge.

But in the small town of Arles, the atmosphere had changed.

The ear-cutting incident had shocked the community, and many residents now saw him as a dangerous man.

His eccentric behavior only fueled their fear and prejudice.

Vincent himself sensed the change: “People are afraid of me,” he admitted in a letter.

Still, he tried to stay optimistic, telling himself that his illness might just be a “local fever” and that he could return to painting soon.

But while he was regaining hope, the townspeople secretly began organizing to have him removed.

Only nine days after his release, on February 26, about 30 residents signed a petition to the mayor demanding his isolation.

The document listed exaggerated accusations — that he harassed women, chased children, and insulted customers in shops.

These claims made his reputation in Arles even worse.

As a result, Van Gogh was sent back to the hospital once again.

He poured his despair and anger into a letter to Theo:

“you can imagine how much of a hammer-blow full in the chest it was when I found out that there were so many people here who were cowardly enough to band themselves together against one man, and a sick one at that…

What misery – and all of it, so to speak, for nothing.I won’t hide from you that I would have preferred to die than to cause and bear so much trouble.” 45

Signac’s Visit — and the Return of the “Attacks”

On March 23, 1889, Theo was busy preparing for his wedding and couldn’t go to Arles himself.

So he asked his friend, the painter Paul Signac, to visit Vincent and check on him.

Paul Signac (1863–1935) was a French Neo-Impressionist known for his pointillist technique.

On his way to Cassis, near Marseille, he stopped in Arles to see Van Gogh.

For Van Gogh, this visit brought a ray of light after a long period of darkness.

Thanks to Signac’s support, Dr. Rey allowed him to go out, and for the first time in about a month, Van Gogh returned to the Yellow House.

Van Gogh’s impression of Signac was very positive.

He later wrote to Theo:

“He [i.e., Signac] was very nice and very straight and very simple…

I find Signac very calm, whereas people say he’s so violent, he gives me the impression of someone who has his self-confidence and balance, that’s all. Rarely or never have I had a conversation with an Impressionist that was so free of disagreements or annoying shocks on either side.” 46

As a token of gratitude, Vincent gave him Still Life with Herrings.

Private Collection

Signac, in turn, admired Van Gogh’s work deeply.

He wrote to Theo:

“I saw his paintings — many of them are excellent, all very interesting…

From what I observed, he seemed perfectly healthy.

His only wish is to work peacefully. Please help him stay in that good state.” 47

However, Vincent’s mental state was not as stable as it seemed.

During Signac’s stay, they spent peaceful days talking about art and literature —

until suddenly, Vincent became agitated and tried to drink turpentine.

Signac was shocked and stopped him just in time, taking him back to the hospital and reporting the incident to Dr. Rey.

But out of compassion, Signac didn’t tell Theo what really happened.

He didn’t want to cause more worry, so he simply reported that Vincent was “in good condition.”

From this time onward, Van Gogh’s attacks became more frequent and cyclical, casting a long shadow over both his mind and body.

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

Collection of the Courtauld Institute of Art

Leaving Arles

Vincent van Gogh couldn’t stay in the hospital forever, yet he also couldn’t return to the Yellow House.

Caught between these two impossible choices, he rented two small rooms in Dr. Rey’s house and tried to live quietly.

But soon, even living alone began to frighten him.

“I feel decidedly incapable of starting to take a new studio again and living there alone, here in Arles or elsewhere” 48

He had once dreamed of turning Arles — “the Japan of the South” — into a community of artists,

a place where “painters of the backstreets” could work together in harmony.

But that dream was now gone.

Worse still, he began to lose confidence in his own future and even in painting itself.

“continuing to spend money on this painting when things could come to the point where there was a lack of money for housekeeping, that’s atrocious, and you’re sufficiently aware that the chance of succeeding is abominable.” 49

“Now, myself as a painter, I’ll never signify anything important” 50

If he couldn’t live alone, he would have to live with someone else.

In the past, he might have gone straight to Paris to stay with Theo.

But now, that option was no longer possible.

There was only one road left:

to admit himself voluntarily to an asylum.

Ironically, it was the very path his late father, Theodorus, had once urged him to take —

a path Vincent had rejected so strongly.

Now, he was choosing it himself.

In early May 1889, Van Gogh quietly left Arles

and traveled northeast to the Saint-Rémy Asylum in Provence.

Niarchos Collection

Part 3 Summary: On van Gogh’s Mental Illness

After leaving the Netherlands, Van Gogh encountered Impressionism and Japanese prints in Paris—experiences that transformed his artistic style.

In the southern town of Arles, he created a remarkable series of works filled with bright, vivid colors—paintings that truly define what we now call “Van Gogh-like.”

Yet in his private life, darkness began to spread.

His friendship with Gauguin collapsed, and soon after, his brother Theo got married.

Mentally unstable and deeply anxious, van Gogh committed a shocking act—he cut off his own ear.

From this time onward, he began to suffer repeated attacks.

He feared the next seizure, never knowing when it would strike.

Collection of The Courtauld Institute of Art

Even today, the true nature of Van Gogh’s mental illness remains unknown.

Many theories have been proposed, but no single diagnosis has been confirmed.

At the time, doctors at the Arles Hospital diagnosed him with “a form of epilepsy.”

It was likely what we now call latent epilepsy—a type that does not cause convulsions but can trigger anxiety, hallucinations, and delusional behavior.

This description matches Van Gogh’s symptoms closely and remains one of the most persuasive explanations.

His lifestyle may also have worsened his condition.

Since his Paris years, Van Gogh had been drinking heavily—especially absinthe, a highly alcoholic spirit.

Combined with poor nutrition, this lifestyle likely strained his brain and may have contributed to his mental decline.

Some researchers suggest that when he abruptly stopped drinking, he suffered withdrawal symptoms such as delirium, possibly triggering his first seizure.

In short, Van Gogh’s illness has never been definitively identified.

It is also possible that several disorders occurred together rather than a single cause.

Even today, mental and neurological illnesses can be difficult to treat—let alone in the late 19th century, when medical imaging such as MRI or X-ray did not yet exist.

Despite living with such a difficult condition, Van Gogh continued to fight through the seizures and kept painting.

How did he live and what did he create in Saint-Rémy and Auvers?

The story continues in Part 4…

Further Reading

・Food Safety Commission, “Hazard Summary Sheet (Draft) (Mercury),” Symptoms of Poisoning, https://www.fsc.go.jp/sonota/hazard/osen_1.pdf, Accessed May 3, 2024

・Wikipedia “梅毒の歴史 (history of syphilis)” https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%A2%85%E6%AF%92%E3%81%AE%E6%AD%B4%E5%8F%B2, Accessed May 3, 2024

・Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, “Workplace Safety Site,” Safety Data Sheet: Mercury, https://anzeninfo.mhlw.go.jp/anzen/gmsds/7439-97-6.html#:~:text=%E4%B8%AD%E6%9E%A2%E7%A5%9E%E7%B5%8C%E7%B3%BB%E3%80%81%E8%85%8E%E8%87%93%E3%81%AB%E5%BD%B1%E9%9F%BF%E3%82%92%E4%B8%8E%E3%81%88%E3%80%81%E8%A2%AB%E5%88%BA%E6%BF%80,%E3%81%8C%E7%A4%BA%E3%81%95%E3%82%8C%E3%81%A6%E3%81%84%E3%82%8B%E3%80%82, Accessed May 4, 2024

・”On the Banks of the River, Martinique”, contemporaries of van gogh, Van Gogh Museum https://catalogues.vangoghmuseum.com/contemporaries-of-van-gogh-1/cat53, Accessed May 25, 2024

・Willem A. Nolen et al.(2020) New vision on the mental problems of Vincent van Gogh; results from a bottom-up approach using (semi-)structured diagnostic interviews.

Sources

- Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 551, Antwerp, on or about Saturday, 2 January 1886, in The Letters of Vincent van Gogh, ed. Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2009). https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let551/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 545. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let545/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 546. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let546/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 552. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let552/letter.html ↩︎

- Translated by the author from The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, vol. 4, translated by Shiro Futami, Misuzu Shobo, 1984, p.1316, quoting Louis Piérard, La vie tragique de Vincent Van Gogh (1939), Editions Correa & Cie. ↩︎

- Gogh Letters, trans. Futami, p.1316. ↩︎

- Gogh Letters, trans. Futami, p.1317. ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 557. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let557/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 559. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let559/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 561. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let561/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 567. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let567/letter.html ↩︎

- Translated by the author from Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith. Van Gogh: The Life. Translated by Kazuya Matsuda, vol. 2, Kokusho Kankokai, 2016, p.55, quoting Coquiot, Gustave. Vincent van Gogh. Paris: Ollendorff, 1923, p.138. ↩︎

- Naifeh and Smith (2016), p.56, quoting Wilkie, Ken. In Search of Van Gogh. Rocklin, Calif.: Prima, 1991, p.30. ↩︎

- Naifeh and Smith (2016), p.56, quoting Rewald, John, Post-Impressionism from Van Gogh to Gauguin, p. 69 ↩︎

- Naifeh and Smith (2016), p.56, quoting van Gogh, Theo, and Johanna van Gogh-Bonger. Brief Happiness: The Correspondence of Theo van Gogh and Jo Bonger. Edited and translated by Leo Jansen and Jan Robert with introduction and commentary by Han van Crimpen. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Muse…, p.160. ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Horace Mann Livens, letter 569. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let569/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Horace Mann Livens, letter 569. ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Horace Mann Livens, letter 569. ↩︎

- Naifeh and Smith (2016), pp.59-60, quoting “Bonger, Andries” to “Bonger, H.C. en H.L.”, June 23, 1886, in Nagera, Humberto. Vincent van Gogh: A Psychological Study. Madison, Conn.: International Universities Press, 1967, p.103 ↩︎

- Naifeh and Smith (2016), p.61, quoting “Gogh, Theo van” to “Gogh, Willemina van”, March 14, 1887. ↩︎

- Translated by the author from Marie-Angélique Ozanne and Frédérique de Jode, Theo: The Other Van Gogh, translated by Hideko Ise and Kyoko Ise, Heibonsha, 2007, p.123, quoting Unpublished letters from Theo to Willemien van Gogh (April 25 and May 15, 1887) ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 577. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let577/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 585. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let585/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Emile Bernard, letter 587. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let587/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 602. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let602/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Willemien van Gogh, letter 678. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let678/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 585. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let585/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 602. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let602/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Willemien van Gogh, letter 678. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let678/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Willemien van Gogh, letter 678. ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 677. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let677/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 549. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let549/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 776. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let776/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 741. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let741/letter.html ↩︎

- Translated by the author from The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, vol. 5, translated by Shiro Futami, Misuzu Shobo, 1984, p.1540, quoting Letter from Gauguin to Émile Schuffenecker ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 712. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let712/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 723. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let723/letter.html ↩︎

- Futami, trans., Complete Letters, vol. 5, p.1540 ↩︎

- Futami, trans., Complete Letters, vol. 5, p.1560 ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 724. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let724/letter.html ↩︎

- Ozanne and Jode (2007), p.152, quoting Unpublished letters from Theo to Johanna (December 28, 1888) ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 728. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let728/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 729. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let729/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 728. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let728/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 750. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let750/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 752. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let752/letter.html ↩︎

- Futami, trans., Complete Letters, vol. 5, p.1598, quoting Letter from Signac to Theo van Gogh ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 760. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let760/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 767. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let767/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 768. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let768/letter.html ↩︎

Comments