Introduction

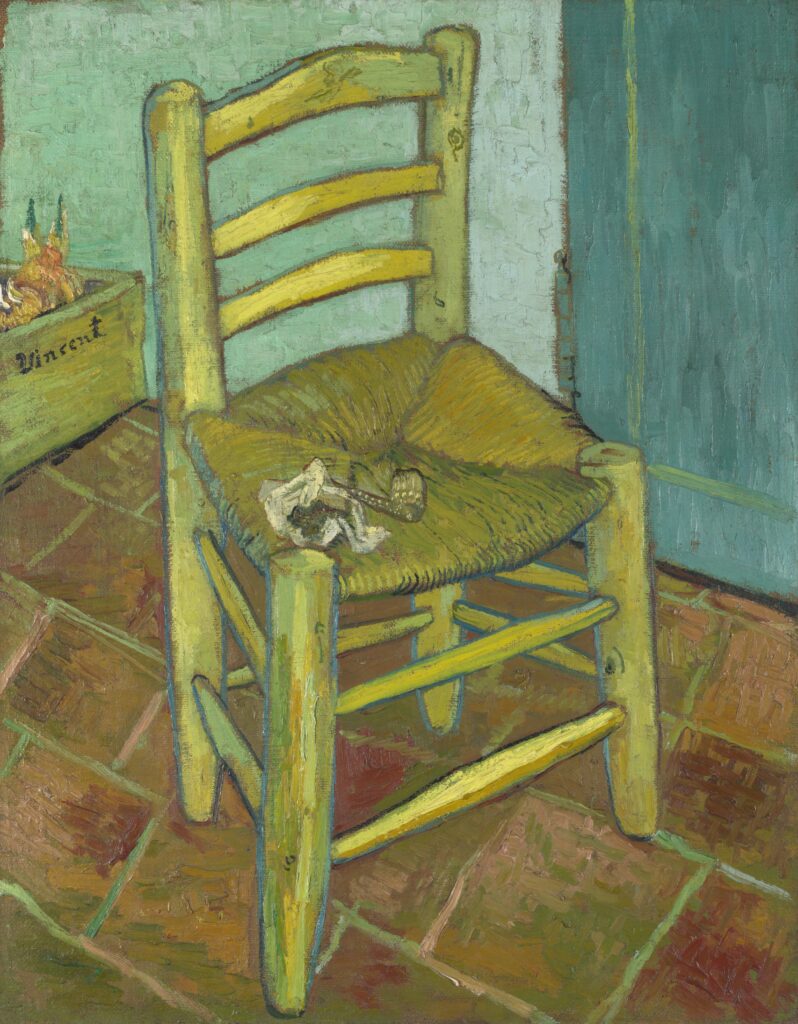

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

When it comes to famous artists, almost everyone knows the name Vincent van Gogh.

Which of his paintings comes to mind for you?

One of my favorites is Van Gogh’s Chair, painted in Arles, southern France.

This work was created during the time when Van Gogh’s use of bright, expressive colors truly blossomed.

At that time, he was living in the “Yellow House” with fellow artist Paul Gauguin.

However, their relationship eventually fell apart, leading to a painful separation.

Perhaps the painting of the chair reflects some of Van Gogh’s unspoken emotions from that difficult time.

Learning about Van Gogh’s life gives us a deeper understanding of his art.

Fortunately, he left behind many letters that reveal his struggles, hopes, and passion for painting in his own words.

In this four-part series, we’ll explore Van Gogh’s life through his letters and highlight the artworks that reflect key moments in his journey.

By the end, you might just discover your own favorite Van Gogh masterpiece.

The Early Years and Student Life

Vincent Willem van Gogh wasn’t interested in becoming an artist as a child.

He decided to pursue painting only at the age of 27 — a relatively late start compared to many other famous painters.

So what kind of life did he lead before that turning point?

In this first part, we’ll follow Van Gogh’s journey from his birth to the years just before he became an artist.

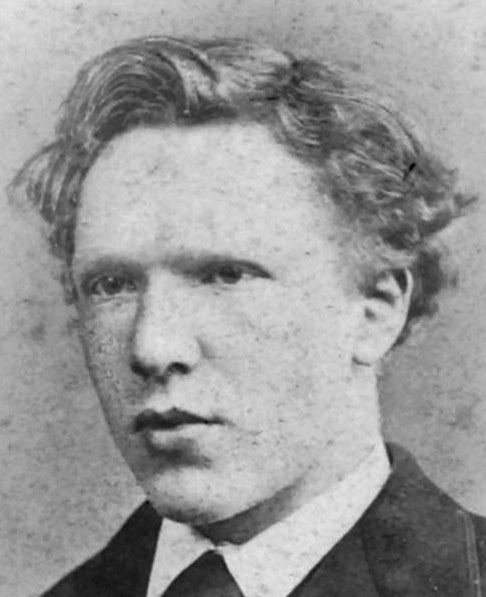

Van Gogh was born in 1853 in the small village of Zundert, in the Netherlands.

His father, Theodorus (known as Dorus), was a pastor, and his mother Anna was the daughter of a bookbinder.

Vincent was named after both his grandfather and an older brother who had been stillborn, carrying the same name.

img: by G.Lanting

As a child, Van Gogh was shy, introverted, and extremely sensitive.

According to the family’s maid, he was “troublesome, contrary, and the least pleasant” of the children.

In her words, he was a “peculiar boy” who often made others feel uneasy.

Instead of playing with other children, Vincent preferred long walks alone in the countryside.

He loved collecting wildflowers and beetles, carefully labeling them with their Latin names.

This early fascination with nature would later become the foundation of his artistic sensibility.

At the same time, his tendency to avoid social contact would also shape many of the difficulties he faced later in life.

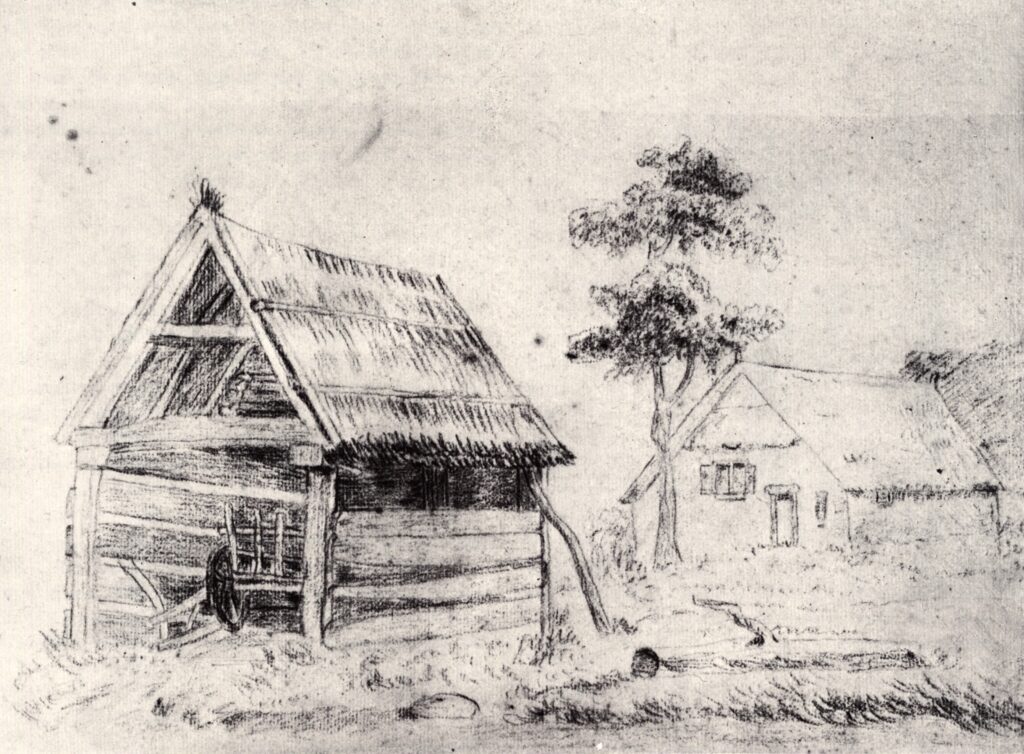

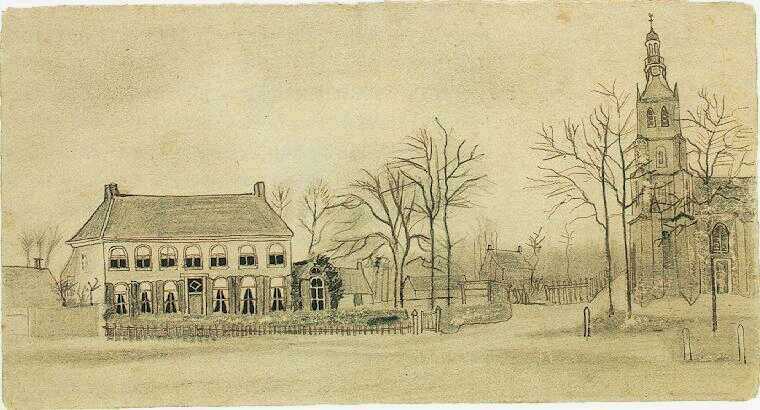

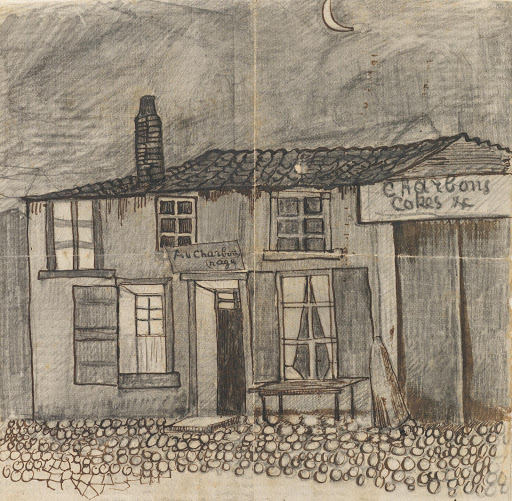

This small drawing was said to be a birthday gift for his father, Dorus.

At the time, Vincent had not yet received any formal art training, but his mother Anna—who had some knowledge of watercolor painting—gave him his first lessons.

Her influence can be seen in the many sketches that Van Gogh included in his letters throughout his life.

Because of his strong-willed and unconventional nature, Vincent became difficult for his parents to manage.

In 1864, at the age of 11, he was sent—almost forcibly—to a boarding school in Zevenbergen, about 20 kilometers from Zundert.

Two years later, in 1866, he transferred to the King William II secondary school in Tilburg.

However, in 1868, just one year before graduation, he suddenly left school and returned home without permission.

Despite being a diligent student—reportedly ranking fourth in his class—Vincent had reached his breaking point.

His parents were deeply disappointed, not only emotionally but also because of the financial cost of his education and lodging.

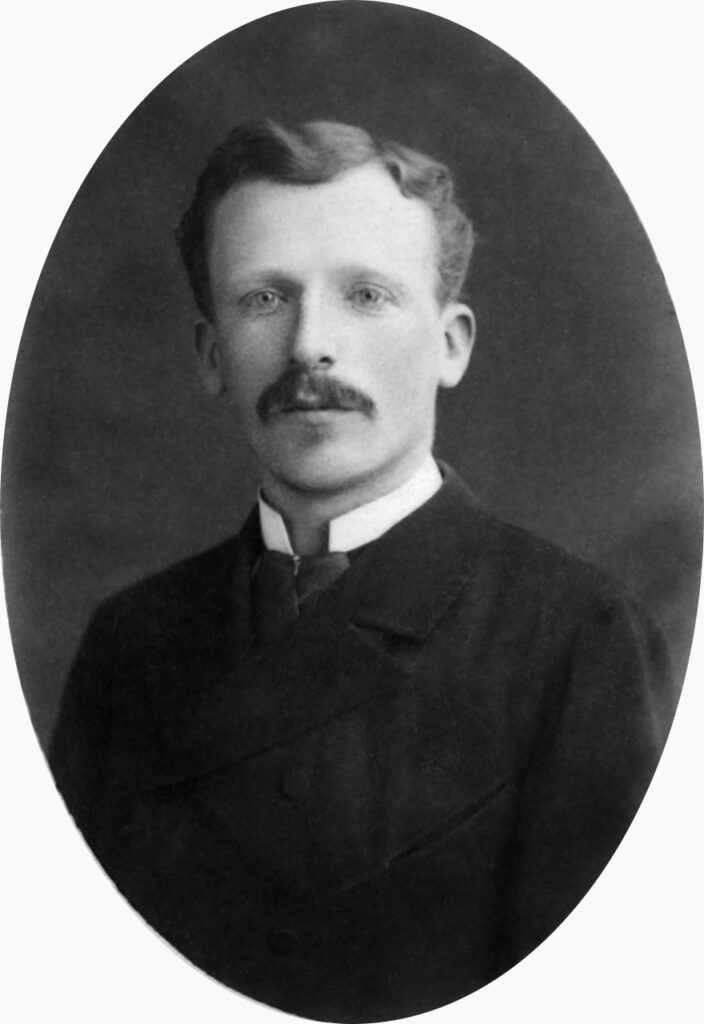

About Theo

Now let’s introduce someone who would become one of the most important people in Van Gogh’s life.

Among his three sisters and two brothers, it was his younger brother Theo, four years his junior, with whom Van Gogh shared a special bond.

They enjoyed playing marbles and skating together during childhood, and Theo’s friendly, cheerful personality balanced Van Gogh’s more serious nature.

Theo is best known for supporting Van Gogh financially during his career as an artist.

But just as important was his role in preserving Van Gogh’s letters.

Van Gogh himself didn’t keep most of the letters he received and often threw them away,

but Theo carefully saved the hundreds of letters written by his brother.

Thanks to these letters, we can trace Van Gogh’s thoughts and emotions in his own words,

and better understand how his life and art evolved.

In many ways, the story of Van Gogh the artist could not exist without Theo the brother.

Van Gogh’s Time at Goupil & Cie

Moving to The Hague: His First Encounter with Art

After leaving boarding school, Van Gogh enjoyed his newfound freedom. But this lifestyle couldn’t last forever.

With the help of his paternal uncle, also named Vincent (known as Uncle Cent), 16-year-old Van Gogh joined the art dealership Goupil & Cie in July 1869, starting as an apprentice at their The Hague branch.

Through this job, Van Gogh began to take a serious interest in art and painting.

Much like his childhood fascination with wildflowers and beetles in Zundert, he now immersed himself in art magazines, visited museums, explored royal collections, and attended galleries and antique markets—all to deepen his knowledge of painting.

Goupil & Cie was not limited to The Hague; it had branches in London, Paris, Brussels, and New York, handling artworks from across Europe and North America.

Although Van Gogh was not yet thinking about becoming a painter, this experience gave him a solid foundation in art knowledge.

Van Gogh’s extraordinary curiosity and passion for art quickly became apparent.

He was soon trusted, and at one point, was entrusted with handling business dealings with high-end clients, receiving high praise from his superiors. By early 1873, he was transferred to the London branch, a sign of his professional progress.

Life Outside Work

Vincent van Gogh seemed to be building a steady career as a young professional.

But behind his success, he struggled with deep loneliness.

During this time, he met a woman named Caroline Haanebeek.

Van Gogh fell in love with her, but sadly, she married another man.

Heartbroken, he started visiting brothels to fill the emotional void left by his loss.

“Enthusiasts, buyers and painters, and all who visited the business, enjoyed dealing with Vincent, and he will certainly go far.”

These were the words of Hermanus Tersteeg, Van Gogh’s supervisor at the Hague branch of Goupil & Cie, in a letter to Vincent’s parents.

However, in reality, Tersteeg found Van Gogh’s lack of social skills difficult to manage.

He kept to himself, never bonded with colleagues, and soon became an outsider at work.

When word spread about his visits to brothels, his reputation began to fall even further.

To spare the feelings of his influential Uncle Cent—one of the firm’s partners—and out of respect for Vincent’s family, the transfer to the London branch was presented as a promotion.

In reality, however, it was closer to a demotion, a polite way to move him out of sight.

An employee who had trouble dealing with people could no longer be trusted to handle clients.

Van Gogh’s passion for art was stronger than anyone’s, but his difficult personality was seen as a risk in the workplace.

Eventually, he was reassigned to the London office, where he handled mostly wholesale business with no direct contact with customers.

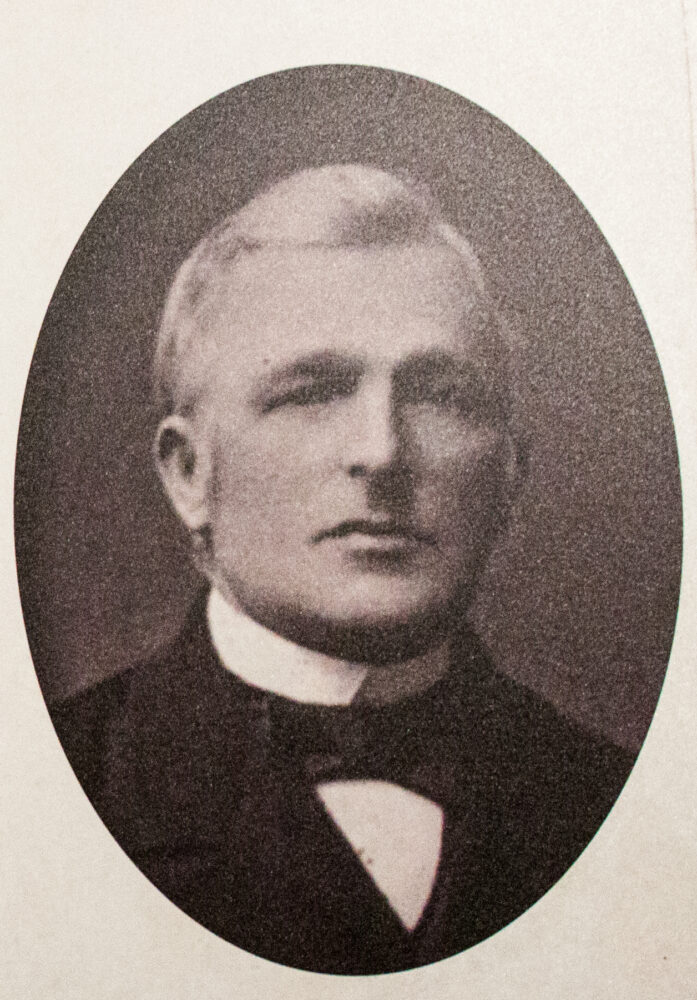

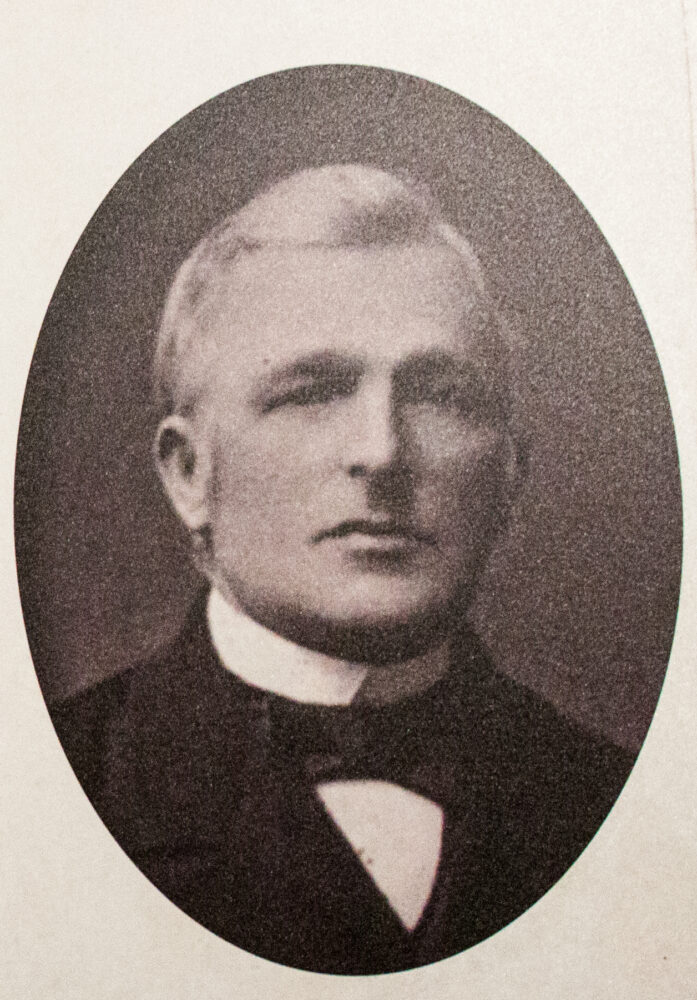

About Tersteeg

Vincent van Gogh often clashed with the people around him. His passionate and emotional nature made relationships difficult, and many friends eventually drifted away.

Yet, there were a few who truly cared for him over the years—and one of them was Hendrik Gerard Tersteeg, his former supervisor at Goupil & Cie in The Hague.

Tersteeg was a talented art dealer who became the manager of the Hague branch in his mid-twenties. Van Gogh deeply admired and respected him.

Even after Van Gogh left the company, Tersteeg continued to look out for him, sending him drawing manuals and watercolor paints to support his artistic efforts.

However, when Tersteeg learned that Van Gogh was pursuing an artist’s career with financial help from his younger brother Theo, he strongly disapproved and refused to recognize Vincent’s work as “art.”

Later, upon hearing that Van Gogh was living with a prostitute named Sien Hoornik while still depending on Theo’s support, Tersteeg was deeply disappointed and eventually cut all ties with him.

For Van Gogh, Tersteeg had been like an older brother. That is why he later came to resent him so intensely—yet he never stopped seeking Tersteeg’s approval.

He kept sending letters and paintings, hoping for some acknowledgment, but Tersteeg never responded. Van Gogh passed away without ever reconciling with him.

After Van Gogh’s death, Tersteeg reportedly burned all the letters he had received from him. Many believe he did this to hide the fact that he had been at odds with someone who was now being praised as a genius.

Still, the fact that Tersteeg had kept those 200–300 letters for many years suggests that his feelings toward Van Gogh were far more complicated than simple hatred.

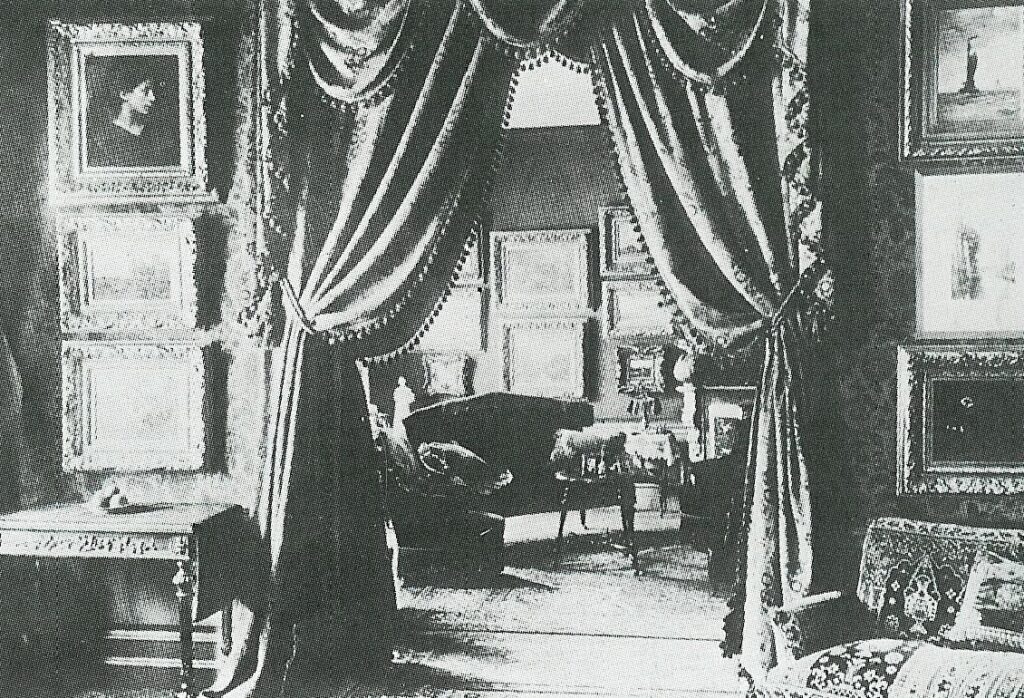

Life in London: Lodging with the Loyers

When Vincent van Gogh was transferred to London, he began exploring British art and culture with great curiosity.

In his letters to his brother Theo, he often mentioned artists such as John Everett Millais, George Henry Boughton, John Constable, and J.M.W. Turner.

“There are some good painters here, though, including Millais, who made ‘The Huguenot’, Ophelia, &c., engravings of which you probably know, they’re very beautiful.” 1

Collection of the New-York Historical Society

Collection of the Tate Britain

In August 1873, Van Gogh had to move out of his first lodging because the rent was too high for his salary.

He found a new place at 87 Hackford Road, where he lived with his landlady Ursula Loyer and her daughter Eugénie.

Although Van Gogh was shy by nature, he seemed to get along well with the Loyer family. For the lonely young man, this home became a rare source of comfort.

” I now have a room, as I’ve long been wishing, without sloping beams and without blue wallpaper with a green border. It’s a very diverting household where I am now, in which they run a school for little boys.”2

According to Johanna Bonger—who later became Theo’s wife and the editor of the Van Gogh Letters—Vincent may have fallen in love with Eugénie.

There is no direct mention of her in his surviving letters, so this remains speculation.

However, a sketch titled 87 Hackford Road, discovered years later in a candy box kept by Eugénie’s granddaughter, Kathleen Maynard, suggests a close and personal connection between Vincent and the family.

(Johanna Bonger, incidentally, played a crucial role in preserving and publishing the Van Gogh brothers’ correspondence. Without her, much of what we know about Van Gogh’s life might have been lost.)

Private collection

Johanna also wrote that Eugénie was already engaged to another man, and that Vincent unsuccessfully urged her to break off the engagement.

She believed this early heartbreak deeply affected him, writing:

“This first great sorrow changed his character profoundly.”

In late August 1874, Van Gogh suddenly left the Loyer home and moved to another lodging.

The reason remains unclear—it may have been due to the failed romance, or perhaps a misunderstanding between Eugénie and Van Gogh’s visiting sister Anna.3

Whatever the cause, leaving the Loyer family must have been painful for him.

Once again alone, Van Gogh became increasingly isolated at work.

His motivation faded, and his attitude toward his job began to deteriorate.

Hoping a change of scenery might help, his Uncle Cent sent him on a short assignment to the Paris branch, but the situation did not improve.

Transfer to Paris: A Growing Passion for Religion and Dismissal

In January 1875, after returning to London, Van Gogh’s attitude toward work still didn’t improve.

He became increasingly difficult for the management, especially with the opening of a new gallery at the London branch.

As a result, in May 1875, he was transferred once again—this time to the Paris branch of Goupil & Cie on Rue Chaptal.

Around the time he left the Loyer family’s boarding house, Van Gogh had grown deeply interested in religious books and began reading them with great devotion.

Even after moving to Paris, his enthusiasm for religion did not fade.

In his letters to his brother Theo, who had also joined Goupil & Cie, art-related topics began to disappear, replaced almost entirely by discussions about faith.

It was an extraordinary time in Paris—the Impressionists were changing the art world.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir was painting Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette (1876),

and Claude Monet was creating Woman with a Parasol (1875).

Collection of the Musée d’Orsay

Collection of the National Gallery of Art

During his earlier years at the Hague branch, Van Gogh might have been excited by these new artistic movements and studied them with passion.

But now, his heart was entirely taken over by religion.

He left no record of any interest in Impressionism.

Over time, Van Gogh became more ascetic and started to question the commercial values of Goupil & Cie.

His motivation for work declined, while his spiritual passion continued to grow.

On Christmas Day 1875, he left Paris without permission to visit his family in Etten, where his father Theodorus had been transferred.

This unauthorized trip ultimately led to his dismissal from Goupil & Cie on April 1, 1876.

It was the end of his career as an art dealer—and the beginning of his search for a deeper spiritual purpose.

Van Gogh Becomes a Teacher

Theo’s Success, Vincent’s Struggles

While Vincent van Gogh was struggling after being dismissed from Goupil & Cie, his younger brother Theo was steadily finding success.

In January 1873, Theo joined the Goupil branch in Brussels, the same branch where his brother had once worked. That November, he was transferred to the Hague branch, where Vincent had also been employed.

Unlike his older brother, Theo was sociable, calm, and well-liked. He quickly gained the trust of H.G. Tersteeg, the branch manager, and earned high praise from Uncle Cent, one of Goupil’s partners.

Uncle Cent, who had no children of his own, had once hoped that Vincent would take over the business.

But after seeing Vincent’s unstable career, his hopes gradually shifted to Theo.

A Second Chance in England

After losing his job at Goupil, Van Gogh was planning to return home to his family in Etten.

Just then, a letter arrived—from a school in Ramsgate, England, offering him a teaching position.

It felt like a message of salvation.

Finally, he could face his parents again with a sense of dignity.

After spending a few weeks at home, Van Gogh boarded a ship to England on April 14, 1876.

Collection of the Van Gogh Museum

Drawn Toward the Church

In Ramsgate, Van Gogh began working as a teacher at a boarding school run by William Port Stokes.

However, disagreements over salary soon led to another dismissal.

Determined to find work, he accepted another teaching position that July at Holme Court in Isleworth, West London.

This school was managed by Reverend Thomas Slade-Jones, and Van Gogh quickly became involved not only in classroom teaching but also in Sunday school and Thursday evening services.

He visited sick students and took part in various charitable activities, earning the trust and respect of Reverend Jones.

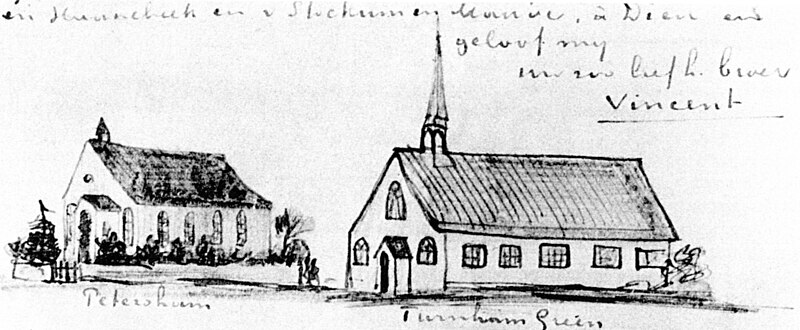

Before long, he was invited to lead services at the Methodist Chapel in Petersham, in southern England.

By October 1876, Van Gogh stood at the pulpit for the first time—an experience that deeply strengthened his desire to become a minister.

Van Gogh included a sketch of these churches in one of his letters to Theo.

Harsh Realities

In December 1876, Van Gogh returned home to Etten once again.

But his parents strongly opposed his plan to continue his teaching work.

His father Theodorus, through Uncle Cent, had already arranged a more stable position for him, and also advised Vincent that becoming a pastor would require several years of study.

Faced with this reality, Van Gogh reluctantly set aside his dream—at least for the moment.

Yet deep inside, the fire of faith still burned.

The Path Toward Becoming a Clergyman

To Dordrecht – Working at a Bookstore

The third building from the left is the Brusse & Van Braam bookstore where Van Gogh worked.

With the help of Uncle Cent once again, Van Gogh found employment in January 1877, at the age of 23, at the Brusse & Van Braam bookstore in Dordrecht.

Although he dutifully carried out his assigned tasks, he showed little interest in book sales and spent much of his time translating the Bible.

Unable to give up his dream of becoming a clergyman, Van Gogh sought advice from Reverend Keller van Hoorn in Dordrecht, but, much like his father Theodorus, the pastor discouraged him from pursuing this path.

He also spoke about his aspiration to become a minister with Braat, the son of the bookstore’s owner. When Braat remarked, “But look at your father: after so many years he’s only been given little places like Etten and De Leerdam. It’s not such a good story. “Van Gogh became visibly upset and replied,

“My father is absolutely in his rightful place, a true pastor.”4

Even when his dream of becoming a clergyman was dismissed, Van Gogh continued to hold deep respect for his father.

Although his growing religious fervor is often attributed to heartbreak and social isolation, at its core lay a genuine admiration for his father that had been present since childhood.

At the bookstore, Van Gogh remained rather isolated, yet he developed a close friendship with his roommate, Paulus Henricus, who was studying to become a teacher. The two often went on walks together.

Later, Henricus described Van Gogh as someone whose “religious feelings were broad and noble,” while also admitting that “he was utterly unsuited for the work at the bookstore.”

According to him, Van Gogh devoted all his free time to religion—reading the Bible and drafting sermons. Still, he concealed his struggles from his parents, writing that he was “satisfied” with his work at the shop.

When Henricus stayed at the Van Gogh family home in Etten, he spoke to Vincent’s mother, Anna, about the reality of his situation. Learning that her son was unhappy with his work and that his only wish was to become a minister deeply pained her.

Upon hearing Henricus’s report, Theodorus finally relented.

He agreed to let Van Gogh pursue the path of ministry—on the condition that he would take the entrance exam for the Faculty of Theology at the Royal University.

Van Gogh’s maternal uncle, Reverend Johannes Stricker, and his paternal uncle, Jan van Gogh, both promised to help with his studies and housing.

Only Uncle Cent, who knew Vincent’s temperament well, opposed the idea and refused financial support.

Reverence for His Father and Nostalgia for Zundert

Shortly before Henricus’s visit to the Van Gogh home in Etten, Theodorus had written to his son in Dordrecht, informing him that Aertsen, a farmer from his former parish in Zundert, was gravely ill.

This news stirred in Van Gogh both a deep sense of religious duty and nostalgia for his hometown.

Overcome with emotion, he borrowed travel expenses from Henricus, boarded the last train of the day, and set off for Zundert.

After reaching the final station, he walked nearly 20 kilometers through the night and waited until dawn for Aertsen’s family to awaken.

When morning came, he learned from the farmer’s children that their father had already passed away the night before.

Overwhelmed with sorrow, Van Gogh read passages from the Bible to the grieving family and stood beside the body.

He later recorded the scene with reverent intensity:

“I’ll never forget that noble head lying there on the pillow; one saw, besides the signs of suffering, an expression of peace and something holy. Oh, it was so beautiful, I’d say that it spoke of all the singularity this land has and the life of these Brabant folk.”5

Afterward, Van Gogh continued on foot to Etten to visit his parents unexpectedly—having walked a total of 25 to 30 kilometers without rest.

This extraordinary determination later became the driving force behind Van Gogh the painter, and his compassion for the poor would become a defining theme of his Dutch period.

However, upon hearing about the incident, Theodorus felt both pride and concern—admiring his son’s devotion to Zundert yet troubled by his impulsive nature.

He expressed his mixed feelings in a letter to Theo:

“Theo, what do you think about Vincent showing up out of the blue and surprising us again? I wish he’d been a bit more careful.”6

In May 1877, at the age of 24, Van Gogh moved into his Uncle Jan’s home in Amsterdam to prepare for the theology entrance exam.

Although his uncles provided generous support, Theodorus could not entirely dismiss his doubts about whether his son was truly suited for the clergy.

Before long, those doubts would prove to be justified.

To Amsterdam: Months of Study and Struggle

Uncle Jan and His Ties to Japan

While studying in Amsterdam, Vincent stayed at the home of his uncle, Johannes van Gogh, known in the family as Uncle Jan.

He was the elder brother of Vincent’s father, Theodorus, and at that time served as a naval commander and director of the Amsterdam Navy Yard—a man of high rank and great respect within the van Gogh family.

Interestingly, Uncle Jan also had a personal connection to Japan.

According to Shiro Futami’s A Detailed Biography of van Gogh, he spent about a year in Japan from November 1860 as the captain of a Dutch warship.

Historical records state that he accompanied Dutch Consul-General De Witt to meet Andō Tsushima-no-kami Nobumasa, a senior official of the Tokugawa shogunate.

When Henry Heusken, interpreter and secretary to U.S. Minister Townsend Harris, was fatally attacked by anti-foreign samurai, Uncle Jan even dispatched a detachment from his ship to attend Heusken’s funeral.

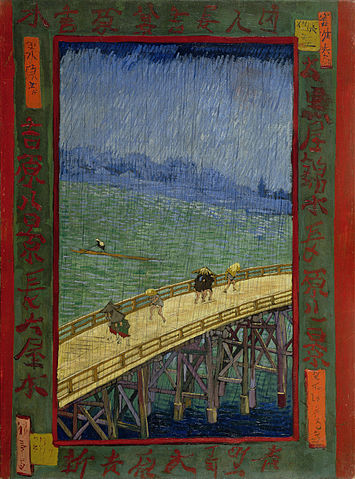

Years later, as an artist, van Gogh became deeply fascinated by Japanese ukiyo-e prints and dreamed of the landscapes of Japan.

He eventually set out for Arles in southern France, believing he might find there a light and beauty similar to that of Japan.

If Vincent had known about his uncle’s adventures in Japan, he would surely have listened with great curiosity and excitement.

However, none of his letters mention this connection, and Uncle Jan had already passed away before Vincent encountered Japanese art—so it seems he never learned of it.

In later years, van Gogh was inspired by Japanese prints and created his own version of Hiroshige’s “Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake.”

Toward the Seminary Entrance Exam

Through the introduction of Reverend Johannes Stricker, Vincent began preparing for the seminary entrance exam under the guidance of Mendes da Costa, a young scholar only two years older than himself. From their very first meeting, the two quickly became close.

Mendes lived with his younger brother, who was hearing-impaired, and Vincent showed deep compassion toward him, always treating him kindly. The family also cared for an aunt with intellectual disabilities. When she once greeted Vincent by mistake, calling him “Mr. Van Holt,” he simply smiled and replied,

“Mendes, no matter how much your aunt ruins my name, she’s a good person. I really like her.”

This anecdote was recalled by Mendes about thirty years later. He remembered Vincent with warmth and respect:

“There was nothing unpleasant about his appearance. […] I cannot understand why his sister once said he looked somewhat rough. […] His hands were strong, yes, and his face expressive—but it was all marked by simplicity. His expression revealed much, and concealed even more.”8

Under Mendes’s instruction, Vincent made steady progress in Latin and Greek. Before long, he was able to translate Latin texts and even read his beloved Thomas à Kempis in the original language.

But when he began struggling with Greek verbs, Vincent’s enthusiasm started to fade. He soon began to question the very purpose of his studies.

“Mendes, do you really believe such dreadful studies are necessary for someone like me—someone who only wants to bring peace to the poor and help them find comfort in this life?”9

Despite Mendes’s efforts to encourage him, Vincent’s progress stalled, and frustration grew. That frustration soon turned inward. Mendes later recalled that Vincent would sometimes beat his own back with a stick when his studies went poorly, or refuse to sleep in bed, instead lying on the hard wooden floor of a shed. Naturally, such behavior affected his studies during the day.

Vincent would even report these punishments to Mendes with a kind of grim sincerity:

“Mendes, I’ve used the stick again.”

“Mendes, last night I punished myself by staying outside.”

Looking back, Mendes said these actions seemed to stem from what he called a kind of spiritual masochism.

The study period, originally planned for two years, ended in less than one. Mendes, realizing that Vincent was unlikely to pass the entrance exam, decided to stop the lessons and advised Reverend Stricker to discontinue his preparation. Vincent, acknowledging the same, accepted the decision—and his brief period of study under Mendes came to an end.

The Catechist

Even before Mendes had officially suggested ending the exam preparation, Vincent often spent his free time visiting churches around the city. During one of these visits, he met Reverend Carl Adler, an English minister whose influence led Vincent to begin teaching Sunday school at the Zion Church.

As his motivation for the entrance exam faded, Vincent began to find a new sense of purpose in his work at the Zion Church. Gradually, he felt called to become a catechist—a person who teaches the principles of Christian faith.

However, in the church hierarchy, a catechist held one of the lowest positions and earned only a modest income. Naturally, Vincent’s father, Theodorus, strongly opposed the idea. After all the financial and emotional support the family had provided, it was difficult for them to accept that this humble role was the result. Theodorus repeatedly urged his son to continue studying for the seminary, but Vincent stubbornly refused.

Thus, his attempt to enter the Amsterdam seminary ultimately came to an end.

Although he had been told from the start that becoming a minister would require years of study, Vincent gave up the path after just one year, feeling that he could no longer continue.

To Belgium

The Missionary Training School in Brussels

On July 5, 1878, at the age of 25, van Gogh returned from Amsterdam to his family home in Etten.

Although van Gogh was eager to begin missionary work as soon as possible, his father, Theodorus, tried to find a way that would allow him to reach that goal more easily.

He discovered a school for evangelists in Brussels, Belgium. At the time, it was said to be easier to obtain a minister’s qualification in Belgium than in the Netherlands — what required six years of study in the Netherlands could be completed in only three years there. Theodorus believed that this would give his son a better chance of success.

In mid-July, Theodorus accompanied van Gogh to Brussels for the entrance interview at the missionary training school. Reverend Thomas Slade-Jones from Isleworth, who had previously supported Vincent, also joined them and brought a letter of recommendation.

After the interview, the school decided to admit van Gogh on a three-month trial basis. If there were no problems, he would be allowed to complete the full three-year course. Thus, in August 1878, van Gogh entered the missionary training school in Brussels as the oldest student in his class.

The curriculum included Latin, just as it had in Amsterdam. However, as he had once declared to Mendes da Costa, van Gogh believed “a preacher doesn’t need Latin” and showed no interest in the subject.

According to one classmate, when the teacher asked, “van Gogh, is this the dative or the accusative case?” Vincent replied provocatively, “Frankly, it doesn’t matter to me.”

He was also not particularly friendly with other students. One classmate recalled that when Vincent was mocked, he glared fiercely and struck the student in anger. During lessons, he refused to use a desk and instead placed his notebook on his knees. When the teacher told him to use the desk, he reportedly replied, “Don’t worry, this works perfectly for me.”

Because of this behavior, van Gogh failed the three-month trial.

Even under Belgium’s more lenient standards, his unwillingness to study and his constant defiance made the teachers conclude that he lacked “the qualities required of a minister.” The decision left van Gogh deeply discouraged.

Out of respect for his father, the school offered to let him remain as a student without pursuing ordination. But van Gogh declined. He instead asked to be sent south to the Borinage region, where he could do real missionary work among coal miners.

Painted after seeing a tavern along the Charleroi Canal in Brussels. The place was often frequented by coal miners.

To the Borinage — The End of His Path Toward the Ministry

In December 1878, van Gogh traveled to Petit-Wasmes, a mining district in the Borinage region of Belgium.

Although he lacked an official missionary qualification, his deep religious passion and a letter of recommendation from his father, Theodorus, earned him permission from the local missionary committee to work there for a six-month probationary period, with a modest salary of fifty francs per month.

Upon his arrival, van Gogh immediately began his missionary work with great zeal. He preached to the miners, visited the sick, and devoted himself entirely to the welfare of the people.

What most captured his heart were the miners themselves. He wrote to his brother Theo:

“These last few days, for instance, it was an extraordinary sight, with the white snow in the evening around the twilight hour, seeing the workers returning home from the mines. These people are completely black when they come out of the dark mines into the daylight again, they look just like chimney-sweeps. Their houses are usually small and could better be called huts, scattered along the sunken roads and in the wood and against the slopes of the hills. One sees moss-covered roofs here and there, and the light shines kindly in the evening through the small-paned windows.” 10

At that time, the miners’ wages had fallen to two-thirds of what they had been just a few years earlier. Explosions, cave-ins, and disease claimed many lives, and labor unions were beginning to form in protest against the mine owners.

Moved by the miners’ suffering, van Gogh shared his fifty-franc stipend with the poorest families, tore up his own clothes to make bandages for the sick, and eventually left his modest lodging to live among the miners themselves in a bare hut, sleeping in a corner by the fire.

This extreme self-sacrifice reflected the same self-punishing tendency that his former tutor, Mendes, had once described as “spiritual masochism.”

Once neatly dressed, van Gogh grew increasingly shabby, until even the miners were shocked by his appearance. Years later, local residents recalled:

“He looked even dirtier than the miners themselves.”

“He had not a single shirt or pair of socks, and I once saw him making a shirt out of a sack.”11

By then, his appearance had drifted far from the dignity expected of a man of the cloth.

When his father, Theodorus, heard of his son’s alarming condition, he traveled to the Borinage and found Vincent thin and weak, lying on a sack filled with straw. He urged him to return to a proper lodging and live in a manner befitting a missionary, but Vincent refused and went back to his hut.

The missionary committee, too, grew concerned about his “excessive devotion” and warned him to moderate his behavior — advice he stubbornly ignored.

His radical acts of self-denial were born of sincerity, a desire to stand beside the workers and share in their hardships. Yet to the eyes of others, his conduct seemed more like madness than faith.

When the six-month probation came to an end, the committee decided not to appoint him as an official missionary and stopped his salary.

Thus, van Gogh’s path toward the ministry was cut off completely.

Part 1 Summary: Did van Gogh Ever Find a Place to Call Home?

From childhood, Vincent van Gogh was known for his temper and difficulty getting along with others. He often found himself in conflict and isolation—a struggle that continued throughout his life.

Yet, there was one place where he seemed at peace: Isleworth, England, where he worked as a teacher under Reverend Thomas Slade Jones.

img: by Mark Percy

During his stay in Isleworth, van Gogh often visited nearby Hampton Court Palace. He admired its gardens and tree-lined paths and was deeply moved by paintings by Holbein, Rembrandt, Leonardo da Vinci, and Titian displayed inside the palace.

In his letters to his brother Theo, he wrote about how happy these visits made him.

Vincent cared deeply for his students. Every morning and evening, he read the Bible, sang hymns, and prayed with them. He once compared the children’s prayers to “the cry of the young ravens that the Lord hears,”12 expressing his gentle affection for them.

His relationship with Reverend Jones was also warm. Impressed by Vincent’s passion, Jones entrusted him with teaching duties and even allowed him to speak publicly in church. When Vincent requested leave to visit his ill brother Theo, Jones handled the situation calmly and with kindness. Later, when Vincent traveled to Brussels for his missionary school interview, Jones wrote a letter of recommendation and accompanied him personally.

Though rarely mentioned in biographies, Reverend Jones was one of the few people who truly understood Vincent—a rare source of comfort and support in his troubled life.

Vincent wished to stay in Isleworth and continue his teaching work.

However, his father, Theodorus van Gogh, did not allow it.

Theodorus was desperate to help his son fit into society and lead a respectable life. Yet, he opposed both Vincent’s work as a teacher in England and his plan to become a catechist in Amsterdam.

His insistence came from family expectations. The van Goghs were a respected, well-connected family: Theodorus was a pastor, his brother “Uncle Cent” a successful art dealer, and another uncle, Jan, a retired navy admiral.

Though Theodorus didn’t expect Vincent to achieve the same prestige, he wanted his eldest son to have a proper profession. That pressure, however, only pushed Vincent further into isolation.

Feeling misunderstood and increasingly alone, Vincent eventually went to the Borinage coal-mining region, where his intense devotion led him to take extreme actions.

The church authorities soon withdrew his missionary license.

When his dream of becoming a preacher was taken away, Vincent fell into despair.

What path would he choose next?

References

・Shiro Futami, trans., The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, vol. 1 (Tokyo: Misuzu Shobo, 1984)

・Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith. Van Gogh: The Life. Translated by Kazuya Matsuda, vol. 1, Kokusho Kankokai, 2016

・Takashi Yoshiya, Melancholy Under the Blue Sky (Tokyo: Hyoronsha, April 25, 2005)

・Shiro Futami, Detailed Biography of van Gogh (Tokyo: Misuzu Shobo, November 1, 2010)

Sources

- Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 11, London, Sunday, 20 July 1873, in The Letters of Vincent van Gogh, ed. Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2009), https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let011/letter.html ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo, Londo, 13 September 1873, letter 13.https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let013/letter.html ↩︎

- Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith. Van Gogh: The Life. Translated by Kazuya Matsuda, vol. 1, Kokusho Kankokai, 2016, p.115. ↩︎

- Translated by the author from Shiro Futami, trans., The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, vol. 1 (Tokyo: Misuzu Shobo, 1984), p.182, quoting M.S. Brussee’s interview with Dirk Braat, May 26 and June 2, 1914. ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 110. https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let110/letter.html ↩︎

- Gogh Letters, trans. Futami, p.174. ↩︎

- Gogh Letters, trans. Futami, p.251 ↩︎

- Gogh Letters, trans. Futami, p.249 ↩︎

- Gogh Letters, trans. Futami, pp.249-250 ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 149 ↩︎

- Gogh Letters, trans. Futami, pp.314-315 ↩︎

- Van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, letter 88 ↩︎

Comments