Blood-splattered art lit by candlelight—have you heard of the Ekin Festival?

Every year on the third Saturday and Sunday of July, the small town of Akaoka in Konan City, Kochi Prefecture, hosts the Tosa Akaoka Ekin Festival. Known simply as the Ekin Festival, it’s a beloved summer tradition in the area.

For just two days, the normally quiet shopping street transforms completely. Lined up along the storefronts are vivid painted folding screens from the Edo period. But these aren’t peaceful landscapes—they’re powerful scenes full of drama, violence, and splattering blood. These works are called Shibai-e Byobu, or kabuki-themed folding screens.

Adding to the surreal atmosphere, the displays are lit not by electric lights, but by real candles. The flickering flames make the images seem to move—creating an intense, almost otherworldly experience. Even better, it’s completely free to attend.

In this article, we’ll introduce this spine-chilling summer festival that Kochi is proud of. But first—who was the artist behind these dramatic paintings, known as “Ekin”?

Venue: Honmachi and Yokomachi Shopping Streets in Akaoka-cho, Konan City, Kochi Prefecture

Who Was Ekin (Hirose Kinzo), the Man Behind the Screens?

“Ekin” was the nickname of Hirose Kinzo, born in 1812 in Shinichi-machi, a town near Kochi Castle during the Edo period. His father was a humble hairdresser, but Kinzo’s artistic talent stood out from a young age.

At 16, he traveled to Edo (modern-day Tokyo) and became an apprentice to a master of the prestigious Kano School of painting. What normally took 10 years to master, Kinzo completed in just three—a testament to his skill.

When he returned to Kochi, he was immediately appointed as an official painter for the Tosa Domain, launching a successful career.

But then—disaster struck.

In his late twenties, Kinzo was caught up in a forgery scandal. Back then, art forgery was a serious crime punishable by death. Though he avoided execution, he was stripped of his official title and banished from the castle town.

Afterward, he continued working as a machieshi (town painter). He eventually moved to Akaoka, where he kept painting. It was during this time that he created many of the Shibai-e Byobu that are still carefully preserved by locals and shown during the Ekin Festival each year.

In his later years, he suffered a stroke that left his right hand paralyzed. Still, he kept painting with his left hand until he passed away in 1876 at the age of 65.

While Ekin also made votive paintings, scrolls, and hanging scrolls, he’s best known for his folding screens based on kabuki plays. These works often depict dramatic, even gruesome scenes with intense emotion and vivid color.

Terrifying yet beautiful. Creepy but captivating. This unique artistic style continues to fascinate viewers even today.

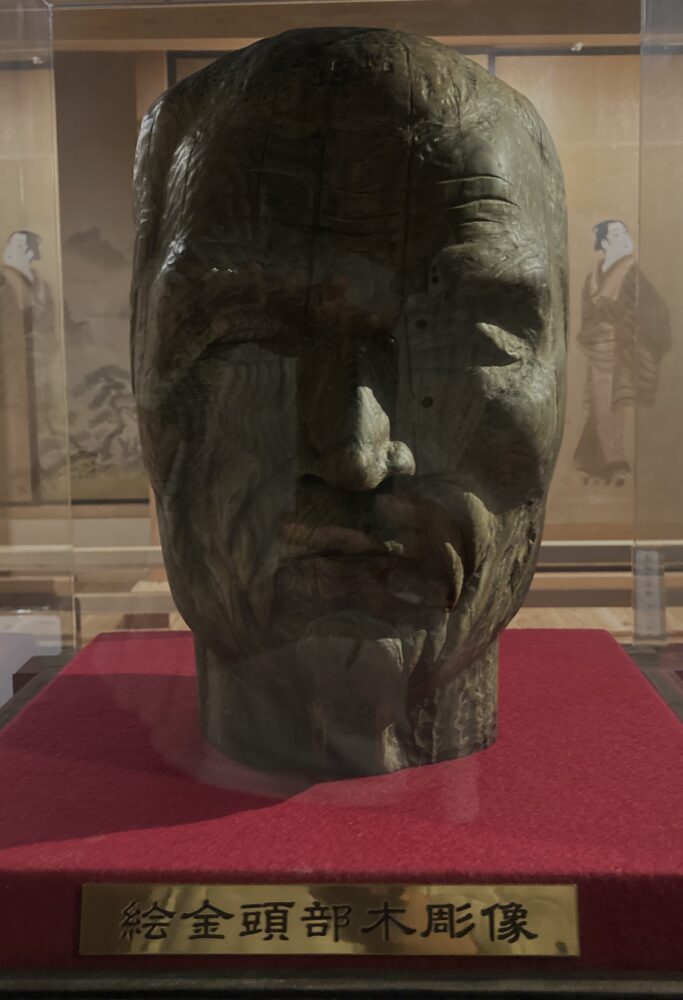

No portraits or photos of Ekin survive, but a wooden sculpture of his head is said to have been passed down in Kochi’s Aki District. According to local legend, a former village head once hosted Ekin while he was painting and asked a temple carpenter named Shimamura Kisaburo to carve a bust of the artist’s head.

Ekingura: Preserving the Story of the Ekin Festival

In Akaoka Town, 23 of Ekin’s original Shibai-e Byobu folding screens still remain. These rare artworks were lovingly passed down through generations in local households.

But Japanese paintings are fragile—they fade easily, they don’t handle humidity well, and they require special care. You might wonder: how did people manage to store such delicate pieces in ordinary homes?

In fact, according to a local wagashi (Japanese sweets) shop owner, there were times when kids set off fireworks in front of the screens or touched them with flour-covered hands during mochi making. These valuable works were treated just like any other family heirloom—casually, and sometimes carelessly. (Museum curators would probably faint hearing this!)

Things got even trickier on festival days. Even today, the Shibai-e Byobu are displayed outdoors during the Ekin Festival. If you’ve ever been to an art museum, you’ll know that Japanese paintings are never exhibited without protective cases. And curators are usually extremely cautious about even the tiniest bit of light exposure.

But at the Ekin Festival? They’re lit by candlelight—outside, in the middle of summer!

Yes, the way these works are displayed is pretty bold. That’s why, to continue this unique and powerful festival, a dedicated facility was needed to properly preserve these folding screens.

So in 2005, Ekingura (the Ekin Museum) was opened.

Ekingura is a specialized facility where all 23 folding screens are carefully stored and restored in a controlled environment. The goal is to protect these delicate artworks and pass them on in the best condition possible to future generations.

But Ekingura’s mission isn’t just about preservation. Above all, they are committed to protecting the tradition of the Ekin Festival itself.

A key part of that tradition? Letting visitors experience the folding screens in person, just as they were meant to be seen—illuminated by flickering candlelight, without a glass case in the way.

Thanks to the passion and dedication of the local community, this eerie yet beautiful world still comes to life every year during the festival.

Note: All artworks in the photo-friendly area are replicas. A few original pieces are displayed in the back room, but photography is not allowed there.

The location of Ekingura: 538 Akaoka-cho, Konan City, Kochi Prefecture

Step Into Ekin’s Dramatic World

Now, let’s take a closer look at some of the Shibai-e Byobu folding screens preserved in Ekingura.

Each one is bold, powerful, and soaked in blood and storytelling—a perfect showcase of Ekin’s dramatic style.

But there’s one thing we absolutely have to say:

Seeing them in person is nothing like seeing them on a screen.

During the Ekin Festival, these folding screens are displayed outdoors, illuminated only by candlelight.

In that dim, flickering glow, the kabuki scenes seem to come alive.

Characters frozen in time start to move, as if they’re stepping out of the artwork and into the summer night.

If these images catch your eye, you really should see them at the actual Ekin Festival.

We promise—it’ll change the way you see them completely.

Ukiyozuka Hiyoku no Inazuma

Scene: Suzugamori

169.0 × 182.0 cm

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

As mentioned earlier, Ekin’s Shibai-e Byobu are based on kabuki plays.

This screen depicts a scene from Act 2 of the play Ukiyozuka Hiyoku no Inazuma.

On the left side, we see Shirai Gonpachi, a samurai who has just been ambushed by bandits at Suzugamori.

He turns the tables and defeats them single-handedly.

Enter Banzuiin Chōbē, a legendary outlaw (shown on the right), who appears and, impressed by Gonpachi’s skill, approaches to speak with him.

The background is littered with the bloodied corpses of the bandits.

At the center of the action: Gonpachi, sword raised, ready to strike again—while Chōbē steps forward, holding out a lantern in an attempt to stop him.

The poses are straight out of kabuki:

Gonpachi twists his body to draw his blade, while Chōbē takes a wide stride and stretches his arm forward with the lantern.

It’s a dynamic and theatrical moment frozen in time.

The use of color is also striking.

A bold red dominates the scene, transforming the presence of blood into something oddly beautiful.

Their costumes are rich in detail, yet the composition remains perfectly balanced despite the visual complexity.

It’s a lavish crime scene, full of violence, drama, and style.

This piece reflects Ekin’s intense passion and dedication to the art of shibai-e—where every drop of blood is painted with love.

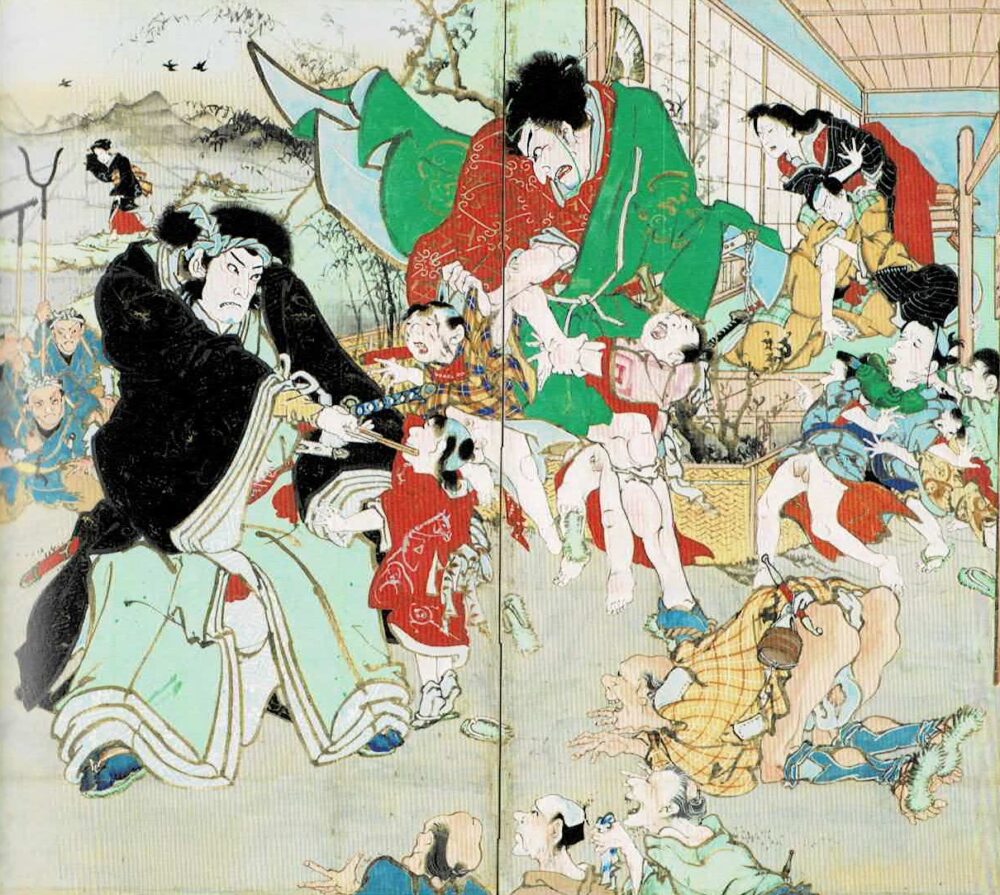

Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami

Scene: The Terakoya (Temple School)

153.2 × 171.3 cm

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Next, we introduce a powerful piece based on a famous kabuki play:

Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami — one of the most emotionally intense stories in classical Japanese theater.

This particular scene is from the well-known “Terakoya” (temple school) act.

In short, the play tells the story of Sugawara no Michizane, a nobleman who is falsely accused and exiled by the villain Fujiwara no Shihei. His young son, Kan Shusai, becomes a target and is hidden in a village temple school.

In this scene, two of Shihei’s retainers, Matsuōmaru (in black, on the left) and Shundō Genba (in the red and green outfit at center), arrive at the school to search for the boy.

On the right, in yellow, is Takebe Genzō, the schoolmaster who is secretly protecting Kan Shusai.

One by one, the men examine the children’s faces. Kan Shusai is moments away from being discovered. The tension is high—Ekin captures this exact moment of suspense.

Look at the top left of the screen: a woman in a kimono glances back toward the school.

Her name is Chiyo, and just moments earlier, she had left her son, Kotaro, in the care of the school with a vague excuse.

That glance? It’s a hint.

Who is she really? And what role does she play in this unfolding tragedy?

The answers—and the heart-wrenching twist—are revealed in the next scene.

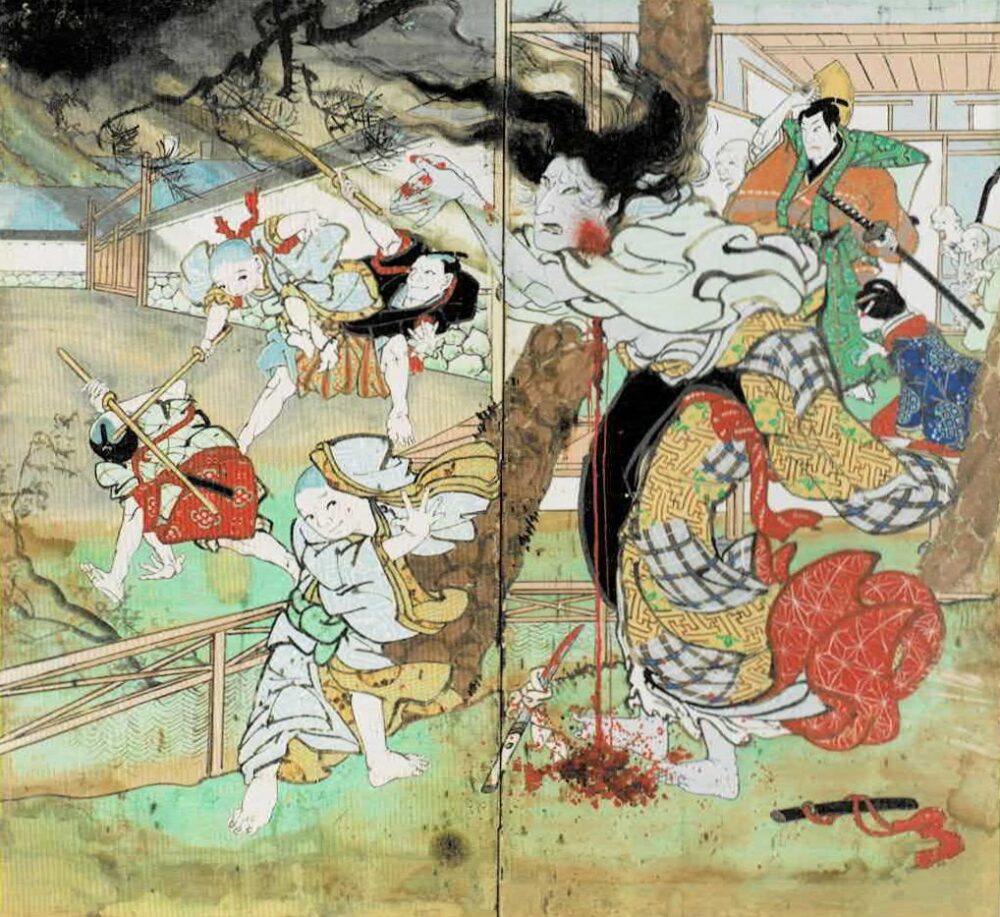

Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami

Scene: The Terakoya (Conclusion)

162.3 × 177.2 cm

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

This second screen continues the dramatic story of the Terakoya.

On the left, we see Genzō and his wife Tonami.

On the right are the searchers—Matsuōmaru and Genba.

And in the center… the severed head of a young boy.

But it’s not Kan Shusai.

To protect the real child, Genzō makes an impossible choice: he sacrifices Kotaro—the boy who was just left in his care that day.

There’s just one problem: Matsuōmaru knows Kan Shusai’s face.

If he recognizes the head as someone else’s, Genzō will surely be killed.

This is a moment of terrifying uncertainty.

Matsuōmaru leans in and stares at the head.

Meanwhile, Genzō clutches a sword, just out of sight, prepared for the worst.

Then something shifts.

Matsuōmaru’s face flushes. His eyes waver. This is no ordinary inspection.

Something inside him is clearly breaking.

He finally speaks:

“This is Kan Shusai’s head.”

With that, the search is declared over, and Matsuōmaru and Genba leave the school.

Genzō and Tonami breathe a sigh of relief—

but it doesn’t last long.

Moments later, Chiyo returns.

Guilt and confusion fill the room… and then—Matsuōmaru comes back.

To everyone’s shock, he tells them the truth:

The boy who was killed—Kotaro—was actually his own son.

Matsuōmaru and Chiyo were his parents.

Though he served the villain Shihei, Matsuōmaru still felt deep loyalty to his former master, Sugawara no Michizane.

To repay that debt, he made the ultimate sacrifice—his own child.

Even as he stood over his son’s body, Matsuōmaru tried to stay strong.

But when Genzō told him how Kotaro had smiled before dying…

Matsuōmaru’s voice trembled:

“Such courage…”

And at last, he wept.

This moment is more than just theatrical tragedy.

It’s a quiet explosion of honor, emotion, and loss.

With just a brush and pigment, Ekin captured the painful beauty of human sacrifice—

and the haunting loyalty that lives beyond blood.

Chōhanagata Meika no Shimadai

Scene: The Kosakabe Manor

162.3 × 177.0 cm

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Family Ties, Loyalty, and a Deadly Duel

This dramatic artwork is based on a kabuki play called Chōhanagata Meika no Shimadai. Inspired by real political conflicts involving the Chōsokabe clan of Tosa and the Toyotomi and Tokugawa families, the story is set in the Warring States period of Japan.

At the center is Kosakabe Otochika, an elderly samurai (seen on the right), who tries to remain neutral in the war between the Hashiba and Ōuchi clans.

Otochika has two daughters:

- Hasue (right side): Married into the Hashiba clan.

- Mayumi (left side): Married into the Ōuchi clan.

They both visit their father to celebrate his 60th birthday—but things quickly turn into a fierce argument. Each daughter tries to convince their father to support her side in the conflict.

Tired of the fight, Otochika proposes a shocking solution:

He will let their sons—Sasaichi (Hasue’s son) and Matsutarō (Mayumi’s son)—fight to the death. He promises to side with the winner.

Sasaichi wins. Matsutarō dies.

Otochika pledges allegiance to the Hashiba clan.

But then, in a tragic twist, Otochika stabs himself and reveals the truth:

- Hasue is actually his niece, not his daughter.

- Sasaichi (the winner) is his brother’s grandson.

- He gave a real sword to Sasaichi and a blunt blade to his true grandson, Matsutarō.

In the end, Otochika chose loyalty to his brother’s legacy over his own bloodline.

A warrior’s honor came before a father’s love.

Ekin’s Powerful Use of “Blood Red”

Look closely at Mayumi’s vivid red kimono. That striking red appears elsewhere too—on Hasue’s sleeve, Sasaichi’s outfit, and more.

This isn’t random. The red brings rhythm and unity to the painting.

It’s a signature shade known as “chi-aka” (blood red)—made from cinnabar found in Kochi’s local mines.

It’s intense, almost sacred, and often used in Ekin’s works.

img: by JJ Harrison

A Color That Protects

In Kochi folklore, red was believed to ward off evil spirits, especially during summer. That’s one reason why the Ekin Festival is held in July and why folding screen paintings were displayed outside homes—not just as art, but as protective charms.

This red is more than paint.

It’s about life, blood, protection, and honor.

That’s the red of Ekin.

Hananoe Homare no Ishibumi

Scene: Shido Temple

169.0 × 182.0 cm

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Mother’s Prayer, A Boy’s Vow for Revenge

This story is based on a real-life revenge case, first told in ningyō jōruri (puppet theater), not kabuki.

In the feudal domain of Marugame, samurai Tamiya Genpachi is assassinated out of jealousy by fencing master Moriguchi Genta Zaemon. Fearing for the safety of his son Bōtarō, Genpachi’s brother Tsuchiya Naiki hides the boy at Shido Temple and has him take religious vows.

Traumatized, Bōtarō becomes mute.

His loyal nursemaid Otsuji prays for both his recovery and revenge, eventually sacrificing her own life in a powerful act of devotion.

In this scene:

- Otsuji is shown at the center, bleeding but still praying with hands clasped.

- Bōtarō sits, head bowed, in front of her.

- Naiki rushes in from the right, realizing what’s happened.

Then comes the twist.

Naiki reveals that Bōtarō was never truly mute.

His silence was a ruse to keep him safe.

Otsuji despairs—were her prayers meaningless?

But Naiki assures her that Bōtarō’s skill in swordsmanship is thanks to her love and prayers.

To prove it, Bōtarō duels two students—and wins, showing incredible technique and strength.

With peace in her heart, Otsuji passes away, trusting the boy will complete his mission.

“Two Moments in One Painting”

Did you notice there are two Bōtarōs in the painting?

This visual technique is called “iji dōzu-hō”—the simultaneous depiction of different times in a single image.

In one scene, Bōtarō mourns Otsuji’s death.

In another, he’s shown fighting in the future.

It’s like a comic book split into panels—but all within a single painting.

This method adds dramatic storytelling power to the folding screen format, a signature of Ekin’s theatrical style.

Look for other examples of this technique in his work—you’ll be amazed!

The Ekin Festival and the Artist Behind the Blood-Red Paintings

What Makes Ekin’s Art So Striking?

One of the most striking features of Ekin’s painted folding screens is his intense use of bright red—known as chiaka, or “blood red.”

This powerful use of color has led some to call his works “bloody pictures.”

But while Ekin’s works are dramatic, they’re not the same as other so-called muzzan-e (gruesome prints), such as Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s Eimei Nijūhasshūku series, which featured graphic scenes of violence as the main subject.

In contrast, Ekin’s screens often include some blood, but in a more restrained way than Yoshitoshi’s intense woodblock prints. The shock isn’t in the gore—it’s in the story. The sense of violence is suggested, not always shown.

Many of his works don’t include any blood at all. Instead, the tension builds through facial expressions, composition, and dramatic storytelling. For Ekin, blood wasn’t the point—it was a tool to heighten the emotion and drama of the scene.

by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1867, woodblock print from the Eimei Nijūhasshūku series)

A Port Town and a Kabuki-Loving Painter

So what inspired Ekin to create such bold works?

The answer lies in his surroundings: the town of Akaoka and the people who lived there.

Akaoka was a thriving port town in Ekin’s day, a hub of trade and culture.

Theater culture from cities like Osaka would arrive quickly, and locals were true kabuki fans—with a sharp eye for quality.

That’s why Ekin started painting kabuki-themed screens.

And he wasn’t just any artist—he was a kabuki superfan himself.

He even named his own son after a kabuki character.

A talented painter with deep love for kabuki, creating for kabuki-loving townspeople—

this special relationship helped Ekin’s screens become more than just dramatic pictures.

They became living stories.

More Than Theater Portraits

In Ekin’s time, most theater art was like modern fan posters—portraits of famous actors in signature poses.

Ekin did something different.

He didn’t paint actors or performances—he painted the story itself.

Using bold compositions, expressive faces, and techniques like multi-time composition (where two moments appear in one image), he captured the drama, emotion, and turning points of kabuki scenes.

He brought together the precision he learned from the Kano school and the passion he felt for kabuki, all for the people of Akaoka.

The Meaning Behind the Red

Akaoka faces the Pacific Ocean.

In the old days, locals believed that during the summer Obon season, not only spirits of ancestors but also evil spirits and plague gods would come across the sea.

To protect their homes, people began placing Ekin’s dramatic folding screens at their doorways.

Over time, the displays became a way to pray for protection, good harvests, and family safety.

That tradition lives on today as the Ekin Festival, held every July on the third Saturday and Sunday.

No glass cases. No modern lighting.

Just candlelight and street displays—filling the town with eerie beauty.

Experience a Living Tradition

Imagine it: warm summer night, candle flames flickering, and vivid chiaka red glowing in the dark.

These screens aren’t just art. They’re part of the town’s soul.

If you’re free in July, don’t miss the Ekin Festival in Akaoka.

It’s not just an art event—it’s a one-of-a-kind encounter with a living tradition passed down through generations.

Explore More of Ekin’s World

After soaking in the energy of the Ekin Festival, why not take your visit a step further? The area around Akaoka offers several great spots where you can dive deeper into the world of Ekin and his art.

Benten Theater (Benten-za)

Located just across from the Ekingura, Benten Theater is a beautifully restored wooden playhouse modeled after a Meiji-era kabuki theater. With tatami seating and a traditional “hanamichi” stage runway, it’s full of nostalgic charm.

Throughout the year, it hosts performances like comedy shows and storytelling, but during the Ekin Festival, something special happens—real kabuki performances take place! You might even see a play that matches the dramatic scenes from Ekin’s painted screens.

Don’t miss the chance to experience live kabuki in a historical setting.

▶Visit Benten-za Website

ACT Land: Creative Fun for All Ages

Comments