Monet planned not only the canvases, but also how they would be shown: the shape of the room, the way light would fall, even how people move through the space. In recent years, the Grandes Décorations have drawn attention as an early form of what we now call installation art .

In this article we’ll trace why Monet kept returning to his pond and how he arrived at the Grandes Décorations — the background, the drama, and the meaning behind these works, explained clearly and carefully.

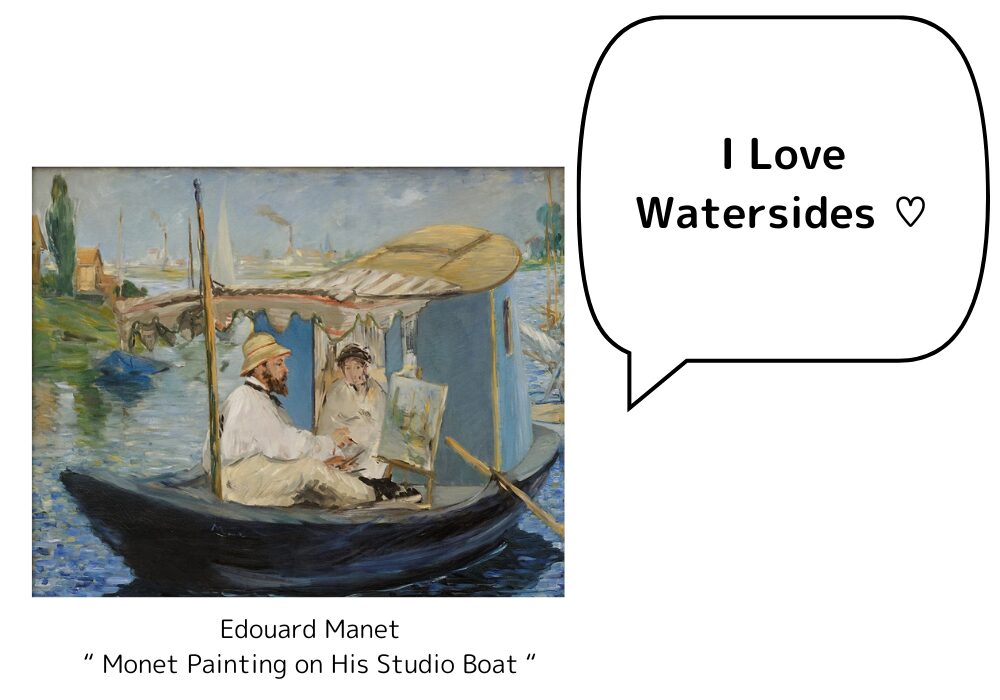

At one point, he even used a “floating studio” — a small boat where he set up his easel and painted while floating on the water.waterside scenery was especially meaningful to him .

Where the Seine meets the English Channel, the sky and water blend into one airy, atmospheric scene. Growing up in such a place, it’s no surprise Monet was drawn to the theme of water throughout his life.

In this sense, Le Havre was the true beginning of Monet’s career: a place filled with memories of water, light, and sky. You could say that Monet’s lifelong fascination with water — later seen in the Water Lilies series — first took root here.

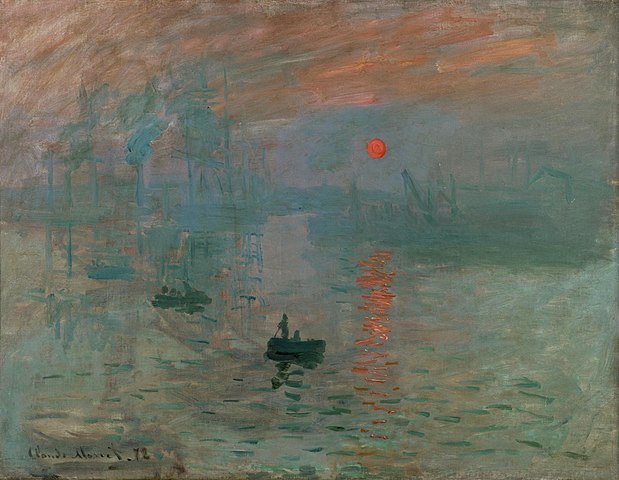

Before Impressionism, European painters usually worked indoors, in their studios.outdoors , capturing natural light as it changes from moment to moment.

The direct sunlight, the reflected light bouncing off surfaces, and the soft colors created by shadows — they pursued all of these fleeting effects.

The sky reflected on the pond, shadows distorted by wind, and the glowing shapes of bridges and trees drifting across the water — these were what truly fascinated Monet.

For him, the lilies and the garden were simply elements in the composition.the light shimmering on the water’s surface .

In 1883, Monet was searching for a new home after leaving Poissy.Giverny .

Monet was instantly captivated by its lush, green scenery.the place he would call home for the rest of his life .

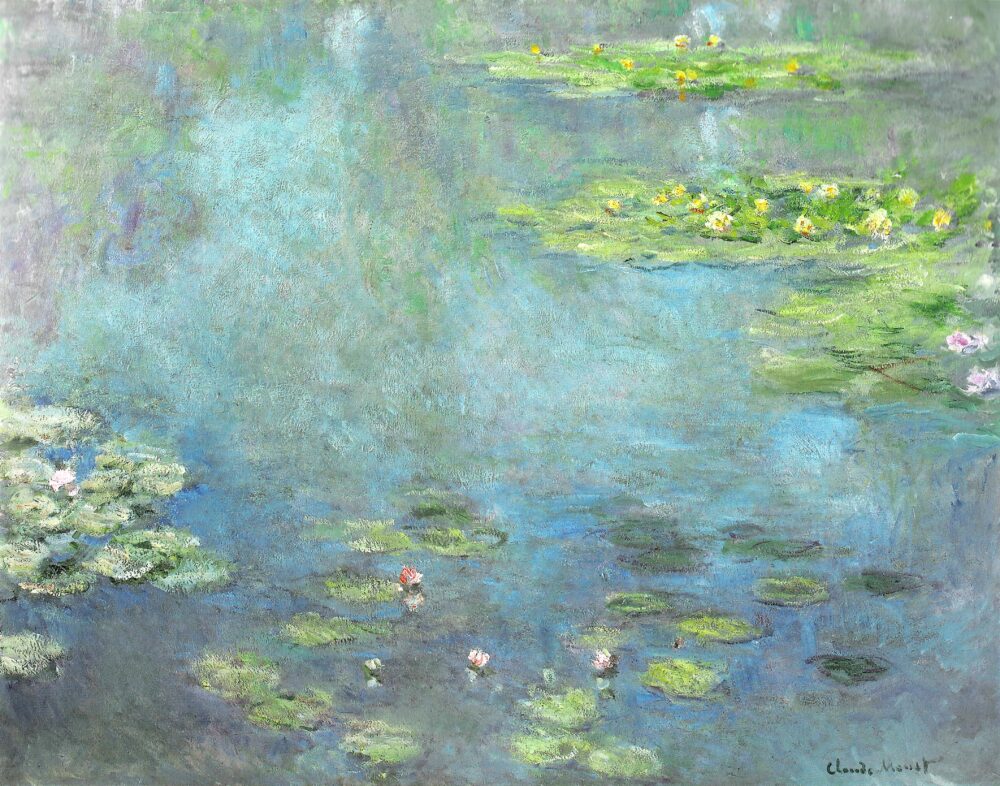

The Stage Monet Built for His Water Lilies The Water Lilies we see today were painted in a garden Monet designed himself .

But this garden didn’t exist when Monet first arrived in Giverny.

It wasn’t until ten years later, in 1893 , that he finally purchased that southern plot.bring in fresh water from a nearby river .

The Water Garden in GivernyPierre André Leclercq However, water use in France was strictly regulated at the time, and his first request was rejected immediately.Monet didn’t give up .

This was how Monet’s dream of a Water Garden slowly became reality.

The Japanese Bridge and the Influence of Japonisme Claude Monet ” La Japonaise ” (1870) In the mid-19th century, Japanese ukiyo-e prints and crafts swept across Europe, creating a major trend known as Japonisme .

Dining Room of Monet’s Houseby Globetrotteur17… Ici, là-bas ou ailleurs… If you visit Monet’s House in Giverny today, you’ll find the dining room walls completely covered with Japanese prints.Japanese art influenced Monet’s taste and imagination .

And this influence extended to the design of the Water Garden itself.arched bridge , often called a “Japanese bridge” or “drum bridge.”

This bridge appears frequently in Monet’s early Water Lilies paintings and became one of the key motifs of the entire series.

Utagawa Hiroshige, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo: Kameido Tenjin Shrine Summary of Chapter 2

Monet chose the small village of Giverny as his final home.

The setting of Water Lilies was the Water Garden he designed on his own property.

The Japanese-style arched bridge he built became a major motif in the early Water Lilies paintings.

Water Garden’s Japanese BridgeMichal Osmenda Chapter 3

The Earliest Water Lily Paintings Monet began painting his Water Lilies around 1895.

The first type features the Japanese-style footbridge as the main subject.

The second type focuses on the water-lily blossoms themselves .

Compared with Monet’s later paintings, these early Water Lilies are a bit more realistic.the bridge and the lily flowers .

国立西洋美術館蔵(寄託)《睡蓮》(1897-1899年頃)

The First Series Featuring the Footbridge Monet’s next major project was a large group of paintings centered on the Japanese bridge .the First Series , shows Monet exploring changes in light more deliberately than in his earliest works.

To capture different moments and different qualities of light, Monet painted the same view and same composition again and again.12 paintings from 1899 and 6 paintings from 1900 , for a total of 18 surviving works .

The 1899 paintings have an almost symmetrical composition, wrapped in brilliant shades of green .

In contrast, the 1900 paintings shift the viewpoint slightly to the left , adding a patch of brown earth in the lower-left corner.

These works are believed to have been painted from the west side of the garden, facing east .late-afternoon sun , making it easy to imagine Monet slowly brushing the canvas in the warm, slanting light.

monet Bassin aux nympheas et sentier au bord del’art

オルセー美術館蔵《睡蓮の池、バラ色のハーモニー》(1900年)

Summary of Chapter 3

Monet’s earliest Water Lilies are more realistic compared with his later works.

Clear motifs such as the Japanese bridge and water-lily blossoms play a central role.

In the First Series , Monet painted the Japanese bridge repeatedly to explore changing light .

Chapter 4

Monet Gains Real Fame Through His Water Lilies In 1901, Monet began enlarging his pond.

From 1903 to 1908, he painted what is known today as the Second Series of Water Lilies .“Water Lilies: Series of Waterscapes” at the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris.

The exhibition was a major success.“the greatest living painter.” The Second Series firmly established his reputation.

The Landscape Disappears — Monet Looks Down at the Water ” Water Lilies, The Clouds ” (1903, Private Collection) In early works of the Second Series , such as Water Lilies, The Clouds

But soon after, Monet’s attention shifts almost entirely to the water’s surface — especially to the reflections of light .

Impressionist painters had always tried to capture the complicated effects of natural light: shadows filtering through trees, shimmering highlights, and colors floating in the air.

Yet Monet went even further.He deliberately zoomed in on this quiet scene and painted it again and again.

Which Way Is Up? One of the most unique groups in the Second Series is the set of vertical compositions painted in 1907.

In several pieces, the reflections are so vivid that the paintings still make sense even when turned upside down .

Is the subject the landscape above the water?ambiguous world where top and bottom seem to switch places .

Monet’s Struggle Originally, Monet planned to present the Second Series in an exhibition in 1907 .he canceled it.

There was just one reason:He could not accept his own paintings.

When he disliked a canvas, he sometimes slashed it with a knife or kicked it.

Monet once said:

” Many people think I paint easily, but it is -not an easy thing to be an–artist. I often suffer tortures when I- paint. It is a-great joy and a great suffering.

Source: Anna Seaton Schmidt, “An Afternoon with Claude Monet”, in Modern Art , Winter, 1897, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Winter, 1897), p.33, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/25609962.pdf , Accessed Nov 16, 2025.

This period became a turning point toward the future Grandes Décorations .

” Water Lilies ” (1908) Summary of Chapter 4

Monet created the Second Series after expanding his pond.

His focus shifted to the surface of the water , and the distant landscape gradually disappeared from his paintings.

Works from this series were shown in the 1909 exhibition, which secured Monet’s reputation.

The Second Series became a major turning point leading toward the Grandes Décorations, and the process involved deep struggle for Monet.

Chapter 5

Today, Monet’s famous Water Lilies series is displayed at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.2 meters high and 91 meters wide

This is the project Monet devoted himself to at the end of his life: the Grand Decoration .Water Lilies he kept painting until his last years.

So, how did this ambitious idea begin?

The “Water Lily Rooms” at the Musée de l’OrangerieBrady Brenot The Idea for the Grand Decoration Began as Early as 1897 The bold idea of “filling an entire space with paintings” came surprisingly early.

In 1897, soon after Monet began painting water lilies, art critic Maurice Guillemot visited Giverny and interviewed him in his studio.

Among the works Guillemot saw was a large panel leaning against the wall. Monet described it as a study for a decorative painting , saying that he wanted to display works like this in a circular room someday.

The plan eventually stalled, but the idea clearly foreshadowed the Water Lily Rooms we see at the Orangerie today.immersive art space .

” Water Lilies ” (1887-1889) Trouble with His Eyes — and a Series of Heartbreaking Losses In 1909, Monet enjoyed major success with his exhibition Water Lilies: Series of Waterscapes .272,000 francs — an incredible amount considering the average Parisian earned about 1,000 francs per year .

His fame and career seemed more secure than ever.

But soon after, Monet’s public activity almost stopped .

One reason was the massive Seine River flood of 1910, which devastated his Water Garden. For a time, he could not paint water lilies at all.

Then came an even more painful challenge:cataracts .

The losses continued.Alice died in 1911.Jean passed away in 1914 at the age of 46.

Alice Hoschedé (1844-1911) Despite all his success, Monet was overwhelmed by grief.

Years of silence followed, and many assumed Monet had effectively retired.

Clemenceau — The Friend Who Brought Monet Back to His Art Monet was supported by his close friend, the politician Georges Clemenceau .

Clemenceau visited Giverny again and again, encouraging Monet:

Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) In April 1914, the two of them went down to a basement room in Monet’s home.decorative panel Monet had once shown to Guillemot.

Seeing it, Clemenceau remembered Monet’s old dream:a circular room filled with large water-lily paintings .

Realizing this was the seed of that dream, Clemenceau urged Monet to try once more .

Monet picked up his brushes again.Grand Decoration began to take shape.

Summary of Chapter 5

After 1909, Monet stepped away from painting for several years.

Behind this were his worsening eyesight , the flood damage, and the loss of his family members .

In 1914, he rediscovered his old “decorative painting. ”

This long-sleeping dream came back to life and eventually led to the Grand Decoration .

Chapter 6World War I and Cataracts — The Expanding “Water Lilies”

Larger Canvases and Blanche’s Support

” Water Lilies, Reflections of Tall Grass ” For the Impressionists, painting outdoors was the norm. Even after paint tubes made materials easier to carry, canvases still had to stay within a portable size.

Most of Monet’s works before 1909 were under 100 cm per side.Grand Decoration , Monet began tackling huge Water Lilies—150 cm per side, and sometimes more than 200 cm wide .

But the “Water Garden” was more than 100 meters from the studio.

This is where his stepdaughter, Blanche , became indispensable.

A painter herself, Blanche was the perfect assistant for the temperamental Monet.

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet (1865-1947, portrayed by Monet) War and the Grand Decoration

Newspaper illustration of the Sarajevo incident, July 12, 1914, by Achille Bertolame In 1914, World War I broke out.

People in Giverny began to flee as well—Monet refused to leave .

” I shall stay here regardless, and if those barbarians wish to kill me, I shall die among my canvases, in front of my life’s work.

Source: Christie’s , “Hidden Treasures: Monet’s Saule pleureur et bassin aux nymphéas” , Accessed Nov 16, 2025.

A photo of a French infantry company conducting exercises before the Battle of the Frontiers. During the First Battle of the Marne, the French and British forces counterattacked—famously sending 6,000 troops to the front using Paris taxis. The German advance was stopped, but the war dragged on.Many young artists left for the battlefield , including Fauvist painters André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck.

Monet struggled with the meaning of painting in such dark times.

He wrote to his friend Raymond Koechlin:

” Even if I sulk, nothing changes. I am aiming for the Grandes Décorations . “

(Author’s translation from the Japanese edition)

This is believed to be the first time Monet used the term Grande Décoration .

From this resolve came the Weeping Willow series—trees associated with mourning and healing in Western culture.

Claude_Monet_Saule_pleureur

Claude_Monet_Weeping_Willow

Monet even included the willow motif inside the Grand Decoration itself.quiet prayer for France’s recovery .

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_Clear_Morning_with_Willows3

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_Clear_Morning_with_Willows3 1

Cataracts and the Fear of Surgery

Monet had been diagnosed with cataracts in 1912. By 1915, he wrote:

“ I no longer perceived colors with the same intensity… I no longer painted light with the same accuracy. Reds appeared muddy to me, pinks insipid, and the intermediate and lower tones escaped me. “

Source: Optometrists.org. “Claude Monet’s Art and the Impact of Cataracts .” Accessed November 16, 2025.

Many works from this period burst with fiery colors reminiscent of van Gogh—very different from his earlier soft touch.

” Iris “ His friends, including Georges Clemenceau, urged him to undergo surgery, but Monet resisted .right eye was almost blind , and the vision in his left eye had fallen to 10% .

Finally, in January 1923, Monet agreed to surgery.

Monet’s glasses Summary of Chapter 6

After 1914, Monet’s Water Lilies grew into large-scale works over 150 cm wide .

His Grand Decoration expressed both mourning and hope for a country wounded by war .

From around 1915, cataracts worsened , and this drastic change in vision shaped the bold style seen in his works around 1920.

Willows in the Water gardenMichael Scaduto Chapter 7

The Armistice and Monet’s Big Decision ” A scene from the Armistice, November 11, 1918 “ On November 11, 1918, World War I finally came to an end.

” I am on the verge of finishing two decorative panels which I want to sign on Victory Day, and am writing to ask you if they could be offered to the State with you acting as intermediary .

Source: Musée de l’Orangerie. “History of the Water Lilies Cycle “, Accessed November 16, 2025.

On November 18, Clemenceau visited Giverny. Inside Monet’s studio, he saw a series of enormous canvases—Monet’s long-imagined dream: the “Grand Decorations.”

Instead of accepting just two paintings, Clemenceau proposed something much bigger:circular room entirely covered with Monet’s Water Lilies . For a monument commemorating victory , nothing could be more fitting.

The Dream of the “Wisteria Panels” Hôtel BironJean-Pierre Dalbéra The first proposed location for displaying the Grand Decorations was the Hôtel Biron, now known as the Rodin Museum. Monet agreed to donate his works, but only under strict conditions:

The gallery must be oval-shaped .

It must use natural light from skylights.

These features were essential to immerse visitors in a serene, endless landscape.

Monet also insisted on adding a second decorative cycle—the Wisteria Panels —fully encircling the upper walls of the room.

However, the cost of such specialized construction was enormous.French government rejected the plan .

” Wisteria “ To the Musée de l’Orangerie The next candidate was the Musée de l’Orangerie .

Due to structural limitations:

The Wisteria Panels could not be installed.

The exhibition space had to be divided into two rooms .

Frustrated, Monet even dismissed the architect—causing headaches for Clemenceau.

The contract with Paul Léon, Director of Fine Arts, stipulated that the Grand Decorations would be delivered to the Musée de l’Orangerie in April 1924—two years later .

Musée de l’OrangerieTraktorminze Monet’s Final Years Even so, Monet once again missed his deadline.

Clemenceau, who had spent years supporting Monet’s project, was furious.

In reality, many of the panels were nearly complete by the spring of 1922.Two Willows also appears almost finished in a studio photograph taken in 1917.

Lower-right area of ” Setting Sun The piece believed to be his final effort was Setting Sun not to finish the painting.

Why?chosen, intentionally, to leave the work unfinished .

On December 5, 1926, Monet passed away at the age of 86—without ever seeing the Grand Decorations installed.

“Completed in an unfinished state” —wanted to keep painting for as long as he lived .

Summary of Chapter 7

To celebrate the end of World War I, Monet’s Grand Decorations were chosen for a monumental installation .The original vision included a full cycle of Wisteria Panels above the Water Lilies.

Monet never fully let go of the works, and they were ultimately presented as “unfinished yet complete. ”

Monet’s House in GivernyAmadalvarez Chapter 8

A Dream Finally Realized After Monet’s death, twenty-two panels of the Grand Decorations were carefully removed from his studio in Giverny and brought to the Musée de l’Orangerie.

In May 1927, they were finally opened to the public.

Exhibition in The first room

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_Morning1

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_Morning2

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_Green_Reflections1

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_Green_Reflections2

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_The_Clouds1

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_The_Clouds

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_Setting_Sun

Exhibition in The second room

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_Clear_Morning_with_Willows3

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_Clear_Morning_with_Willows3 1

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_The_Two_Willows1

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_The_Two_Willows2

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_The_Two_Willows3

Claude Monet Morning with weeping Willows1

Claude Monet Morning with weeping Willows2

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_Tree_Reflections1

Claude_Monet_-_The_Water_Lilies_-_Tree_Reflections2

——It was the long-awaited opening.

But the reality was very different.

A Posthumous Backlash: The Return to Order World War I left Europe deeply scarred.stability, balance, and a return to tradition . classical styles .Return to Order

Andre Derain.” Harlequin and Pierrot ” (1924) It was in this atmosphere that Monet’s Grand Decorations were unveiled.

The softly blended light, the blurred outlines, and the almost abstract surfaces felt “too experimental ” and “too vague ” for many viewers.

If Monet had painted haystacks—symbols of labor—or the Seine River—scenes that stirred national pride—public opinion might have been very different.

Instead, the star of the Grand Decorations was an “exotic flower” with no ties to French tradition: the water lily.This was the complete opposite of the clarity and order that postwar France desperately wanted.

As a result, even though the Grand Decorations were Monet’s final masterpiece, they were out of step with the mood of the times—and were not immediately embraced by the public.

The Forgotten Monet and His “Water Lilies” In this climate, almost no one visited the Water Lilies rooms at the Musée de l’Orangerie.

Even after the Return to Order movement had passed and classical painting was no longer in vogue, Monet’s Grand Decorations still failed to gain recognition. moved toward modern art , the Impressionists’ interest in natural light and outdoor effects began to feel outdated .

Before long, the Water Lilies rooms were used for other temporary exhibitions—and eventually even as storage space.unrestored for twenty years .

It’s hard to imagine the Water Lilies rooms being treated this way.The fame of the great master had faded, and Monet himself became a forgotten figure.

Reevaluation by American Artists By the 1950s , Monet made an unexpected comeback. American artists .

When these American painters traveled to France, many of them headed straight to the Musée de l’Orangerie.Grand Decorations and were deeply moved.

Why were they so shocked?they themselves were abstract painters .

In Monet’s soft, blurry outlines and his bold strokes chasing the movement of light, they found the roots of abstract expressionism.

“ The Orangerie is the Sistine Chapel of Impressionism. “

Yet there’s an ironic twist here.

He rejected Neo-Impressionist pointillism, even when painters like Pissarro embraced it.

And still—ironically—it was abstract artists who brought Monet back into the spotlight.

Thanks to them, the Water Lily rooms regained attention, and Monet was rediscovered within the broader story of 20th-century art.

Renovating the Water Lily Rooms As Monet’s reputation grew again, the Orangerie decided to rethink how his Water Lilies should be displayed.

After the Renovation Jason7825 One major change was removing the large exhibition space that had been built directly above the Water Lilies rooms in the 1960s.

In the new design, architects restored the skylights.The entire space is gently illuminated—much closer to the atmosphere Monet originally imagined.

Skylight from OutsideTimothy Brown This lighting is not only for beauty but also for conservation.

Oil paintings are usually protected by varnish, but varnish yellows over time.Grand Decorations .

The renovated lighting system helps protect these fragile works while creating an immersive environment for visitors.

At last, the Grand Decorations were presented with the respect they deserved—

It took nearly 80 years after his death for that dream to come true.

Monet’s Grand Decorations: A Forerunner of Installation Art Maurice Denis, Mural for the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1908–1911)Sailko Painting murals inside public buildings is an ancient tradition.

But Monet’s Grand Decorations were completely different.

He didn’t just paint large panels—he imagined the entire viewing experience .

He designed:

Oval-shaped rooms Natural light from skylights A space where visitors feel surrounded by water

In other words, Monet wasn’t creating only paintings.immersive environment where viewers could step into the world of the water lilies.

This approach unintentionally foreshadowed what would later be called installation art , which became popular from the 1970s onward.entire room into an artwork.

Monet never used that term, of course.Water Lilies rooms was remarkably modern—and far ahead of its time .

Summary of Chapter 8

When the Grand Decorations were first shown, the reviews were terrible .Monet temporarily faded from public memory .

Surprisingly, it was American abstract painters who revived Monet’s reputation.

After a major renovation in 2006, the Water Lilies rooms at the Musée de l’Orangerie finally reached a form close to Monet’s original vision.

The Grand Decorations can be seen today as early examples of what would later become installation art.

Monet’s Grave in GivernyIbex73 Conclusion We’ve now explored Monet’s Water Lilies and their final form, the Grand Decorations .

I hope this article helped you feel Monet’s deep connection to water, the 30-year evolution of his Water Lilies , and the emotion he poured into the Grand Decorations .

One surprising fact is that this monumental project was actually unpopular when it was first shown. Today, more than a million visitors come to the Orangerie each year to see the Water Lily rooms—proof of just how dramatically opinions can change over time.

Even now, Water Lilies feels incredibly fresh for a work painted over a century ago. Every visit reveals something new. If you ever travel to France, make sure to stop by the Musée de l’Orangerie and experience this unique space for yourself.

And don’t forget—several of Monet’s Water Lilies can also be found in museums across Japan. These masterpieces may be closer than you think. If you’re curious, be sure to check out the related article below.

アートおへんろ

All 26 of Monet’s Water Lilies You Can See in Japan: Museums and Artwork Guide

What Are Water Lilies, Anyway? When you think of the Impressionist master Claude Monet, you probably think of Water Lili

Thank you so much for reading to the end.

References

Ross King, Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies .

Hiroo Yasui, The World of Monet’s “Water Lilies” .

スポンサードリンク ( Sponsored link )

Comments