If you want to explore modern art in the ancient city of Kyoto, visit The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto (MoMAK)!

Located in the Okazaki area—a cultural hub filled with museums, Heian Shrine, and libraries—MoMAK introduces a wide range of works focusing on Japanese art from the Meiji period onward.

Opened in 1963, the museum has over 13,000 pieces in its collection, including Japanese-style paintings (Nihonga), Western-style paintings, sculptures, and crafts.

Among them are masterpieces by Kyoto-associated artists such as Shoen Uemura, Tessai Tomioka, and Sotaro Yasui, making MoMAK an essential destination for understanding the development of modern art in the Kansai region.

A Blend of Culture and Modern Architecture

MoMAK also features international works by 19th-century European painters like Odilon Redon and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, as well as modern masters such as Pablo Picasso and Piet Mondrian.

Its diverse collection reflects the museum’s open-minded and global perspective—quite progressive for a city often seen as traditional.

The museum building was designed by Pritzker Prize–winning architect Fumihiko Maki.

With its glass façade and bright, naturally lit galleries, it offers a serene space to appreciate art at your own pace.

Elegant yet understated, the architecture itself captures the refined spirit of Kyoto.

Highlights from the MoMAK Collection

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto (MoMAK) holds five collection exhibitions each year, featuring works from its rich collection.

Because the displays are rotated regularly, it’s a good idea to check the museum’s website before your visit if there’s a specific piece you’d like to see.

▶ [Official Website of MoMAK]

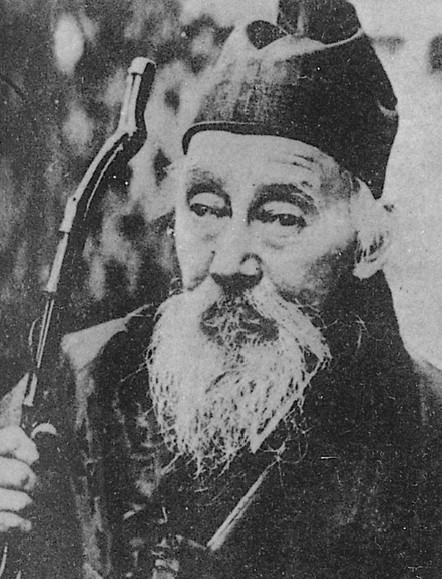

Tessai Tomioka

“View of Mount Fuji and Kankakei Gorge” (1905)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Scholar-Painter Who Captured the Spirit of Japan

Tessai Tomioka is often called “the last literati painter” of the Meiji and Taisho periods.

He was not only an artist but also a scholar, having studied Confucianism, Yangming philosophy, Japanese classics, Shinto, and Buddhism.

Tomioka mastered both Nanga (Southern School Chinese-style painting) and Yamato-e (traditional Japanese painting), making him a rare figure who combined intellect and artistry.

He often said, “My real profession is that of a scholar.”

His motto was, “Read ten thousand books and travel ten thousand miles.”

True to his words, he journeyed across Japan—from Hokkaido in the north to Kagoshima in the south—sketching landscapes that later became the subjects of his paintings.

Japan’s Breathtaking Scenery: Mount Fuji and Kankakei Gorge

“View of Mount Fuji and Kankakei Gorge” is one of Tomioka’s masterpieces, filled with his memories of travel and the keen observation of a literati artist.

This large-scale folding screen stands about 1.5 meters tall and over 7 meters wide, giving it the grandeur of a “panoramic journey across Japan.”

The left screen depicts Kankakei Gorge on Shodoshima Island in Kagawa Prefecture.

Through layers of rugged cliffs and oddly shaped rocks, the Seto Inland Sea unfolds in soft mist—a composition that shows Tomioka’s superb sense of structure.

The contrast between the solid, rocky foreground and the gentle, distant scenery is striking.

img: by 663highland

In the right screen, Mount Fuji rises in the distance, as seen from Jukkoku Pass in Izu.

The curving lines of Suruga Bay and Sagami Bay create a dynamic perspective, blending geography and artistic vision in a way unique to Tomioka.

The rhythm of mountains, sea, and sky gives the viewer the feeling of looking down on the Japanese archipelago from above.

Combining the erudition of a scholar with the compositional skill of an artist, Tomioka painted not just the beauty of nature but also the spirit and memory of each place.

This work is a true masterpiece that reflects both his intellect and his deep love for Japan’s landscapes.

Shoen Uemura

“Preparing to Dance” (1914)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

The Subtle Beauty of Everyday Gestures

Shoen Uemura was a Japanese painter active from the Meiji through the Showa periods.

She is best known for her bijin-ga (paintings of beautiful women), but her true artistry lies in her refined sense of composition, elegant use of color, and sharp eye for capturing delicate human gestures.

She lived during a time of dramatic cultural change, when Western influences flooded into Japan.

Artists across the world, including Van Gogh and Gauguin, were exploring new styles, while writers like Émile Zola were shaping the rise of naturalism and social realism.

In this atmosphere, many artists were expected to depict themes such as poverty, labor, and human rights.

Against this trend, Uemura’s art was sometimes dismissed by critics as “lacking content.”

But she never abandoned her own style.

For her, true realism did not lie in depicting society’s struggles—it was about observing the quiet, genuine moments of daily life.

She sought to reveal the inner dignity and subtle emotions of women through their gestures, posture, and presence.

A Quiet Moment Before the Dance

In “Preparing to Dance,” Uemura’s gentle gaze shines through.

A geisha is shown calmly getting ready to perform, while her companions chat beside her.

Her expression is serene, yet the slight distance in her stance and the still tension in the air convey the quiet focus before stepping onto the stage.

This painting does not depict a grand event or social issue.

Yet within its small, intimate space, there is a deep sense of “living time.”

The scene quietly invites viewers to imagine the emotions and stories behind it.

Uemura stayed true to her aesthetic ideals, refusing to follow artistic fads.

Through this work, her calm determination and belief in quiet beauty can still be deeply felt.

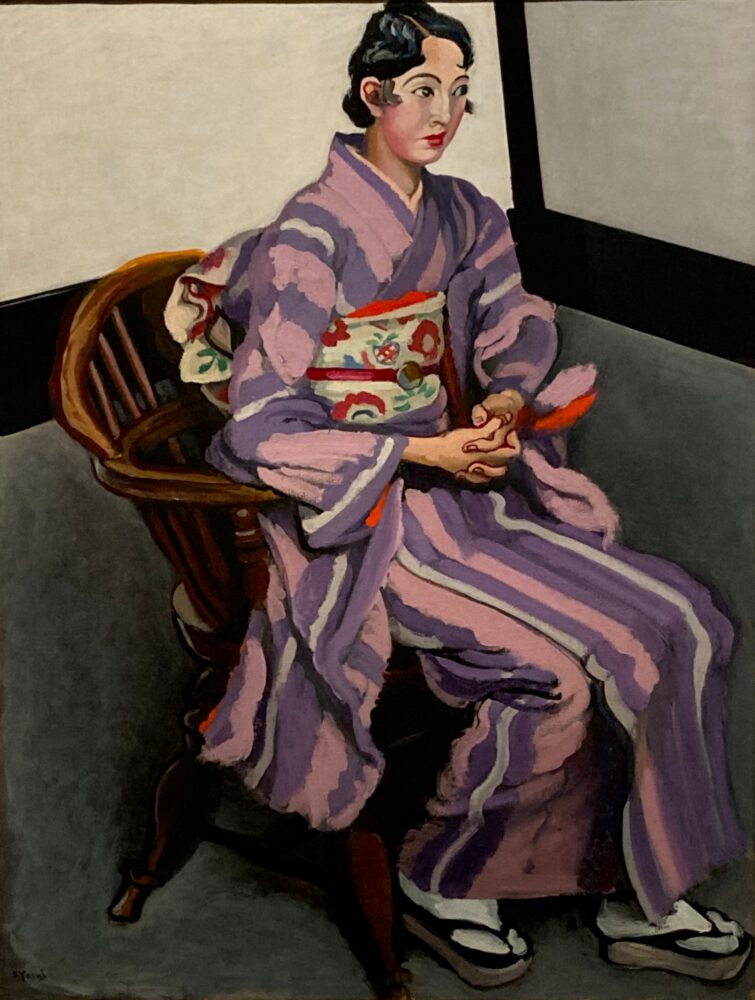

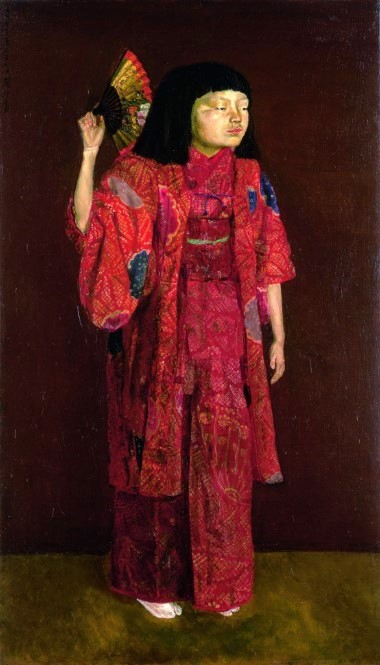

Sotaro Yasui

“Seated Woman” (1930)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Portrait of a Woman in the “Yasui Style”

Sotaro Yasui was a Western-style painter active from the Taisho to the Showa period.

He painted a wide range of subjects, from portraits to landscapes, but is especially known for his distinctive way of depicting figures.

His portraits are characterized by bold forms and a solid sense of structure, a style often called the “Yasui Style.”

He intentionally distorted shapes slightly, creating a sense of strength, volume, and rhythm that made his works instantly recognizable.

Yasui developed this mature style around 1930, more than ten years after returning from his studies in Europe.

“Seated Woman” was painted during this period, when Yasui began to establish his mature style.

A Figure with Powerful Presence

During his time in Europe, Yasui was deeply influenced by Paul Cézanne, and that influence can be seen here.

The figure’s form has a geometric feel, built with firm structure and balance.

Yet his brushstrokes are bold and direct, and the flowing patterns of the kimono are rendered with graceful ease

The thick layers of color give the canvas a sense of weight and presence.

One of the most striking aspects of the painting is the treatment of the face.

The soft, rounded cheeks connect smoothly like the planes of a sculpture, creating a beautiful balance between structure and femininity.

It’s a perfect example of Yasui’s ability to combine form and presence in a single image.

A Structured Space Beyond the Figure

The background also reveals Yasui’s structural approach.

The black-and-white walls and floor are arranged like overlapping planes, reminiscent of Cubism.

However, rather than adopting Cubism as a trend, Yasui expanded his own idea of “form emphasis”—a concept he had explored in his portraits—into the entire composition.

Here, the background is not just a setting; it’s an integral part of the painting’s structure.

The calculated arrangement of shapes creates both stillness and tension, reflecting Yasui’s precision and his deep fascination with form.

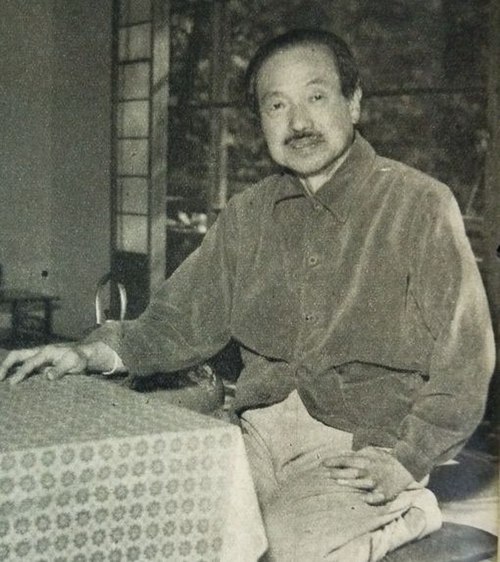

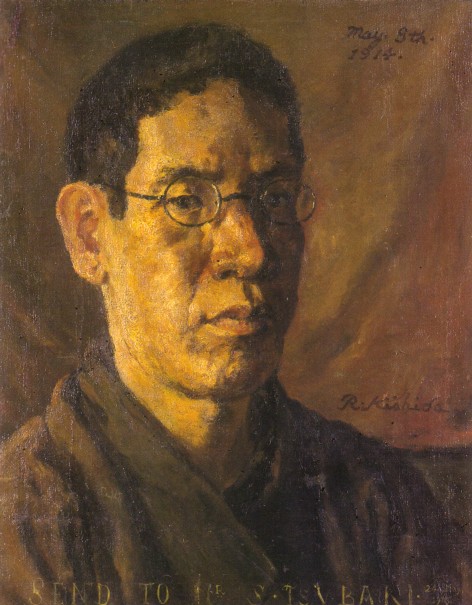

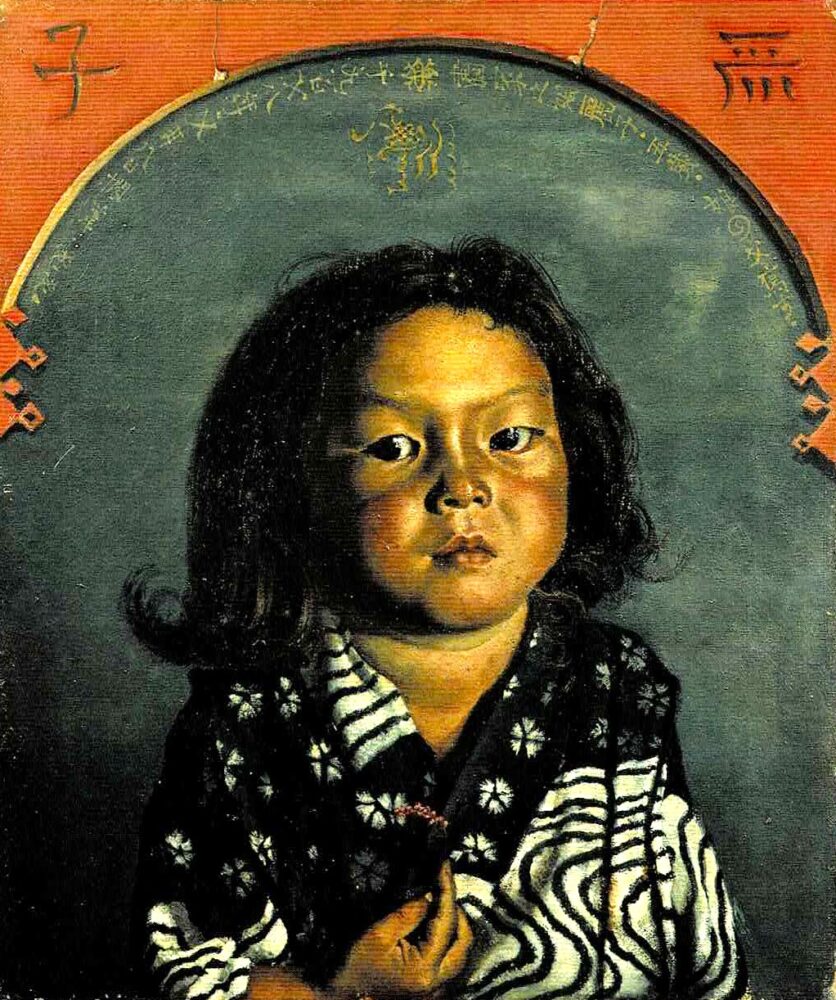

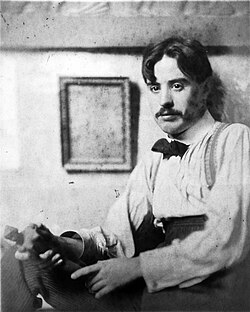

Ryusei Kishida

“Reiko Playing the Shamisen” (1923)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Quiet yet a little haunting — the mysterious gaze of Reiko

A young girl practices the shamisen, a traditional Japanese string instrument.

But her face is strikingly expressionless.

It looks as if she isn’t playing at all, just staring quietly into the empty air in front of her.

The atmosphere feels calm yet strangely unsettling.

The artist is Ryusei Kishida, a leading realist painter of modern Japan.

Early in his career, he was fascinated by classical Western art with its dark tones and solid forms.

But soon he began to ask himself, “What should a Japanese artist truly paint?”

This question led him to pursue a uniquely Eastern sense of realism.

Beyond simple beauty — the deep world of Reiko Portraits

This painting, “Reiko Playing the Shamisen”, was part of that search.

The model is his beloved daughter Reiko, known from the famous Portraits of Reiko series.

An early portrait of Reiko.

In his early works, Reiko appeared soft and innocent.

Here, however, the mood changes completely.

Her faint smile feels stiff, almost mature for a child.

She seems to look not at her instrument, but at something invisible beyond it — creating a subtle, haunting tension.

This is the essence of Kishida’s Eastern realism:

realistic, yet not photographic; quiet, yet deeply psychological.

The stillness of the scene slowly seeps into the viewer’s mind.

It’s a painting that’s hard to describe — unsettling, but unforgettable.

Once you’ve seen Reiko’s gaze, it stays with you.

Kijiro Ota

“Girls” (1915)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

A Japanese Painter Who Studied the Light of Belgium

Kijiro Ota was one of Japan’s early modern Western-style painters.

Unlike many artists of his time, he chose to study in Belgium, where he learned the style known as Luminism.

His teacher was Emile Claus, a leading figure of Belgian Luminism.

Claus’s works combined the brightness of French Impressionism with clear shapes and detailed brushwork similar to Neo-Impressionism. These qualities had a major influence on Ota’s painting style.

Soft Afternoon Light and Quiet Harmony

“Girl” was painted after Ota returned to Japan.

It shows young girls relaxing in the shade of a garden tree, surrounded by the warm glow of afternoon light.

The orange and green kimonos shine softly in the sunlight, blending beautifully with the delicate colors of the trees and ground. The entire scene feels peaceful and full of gentle air.

Western painting techniques and Japanese sensitivity come together naturally here, creating a calm and timeless mood that invites you to keep looking.

Around the same time, another Japanese painter, Torajiro Kojima, also studied under Emile Claus in Belgium.

When you compare their works, you can see how each artist developed a different way of expressing light—another fascinating story in Japan’s art history.

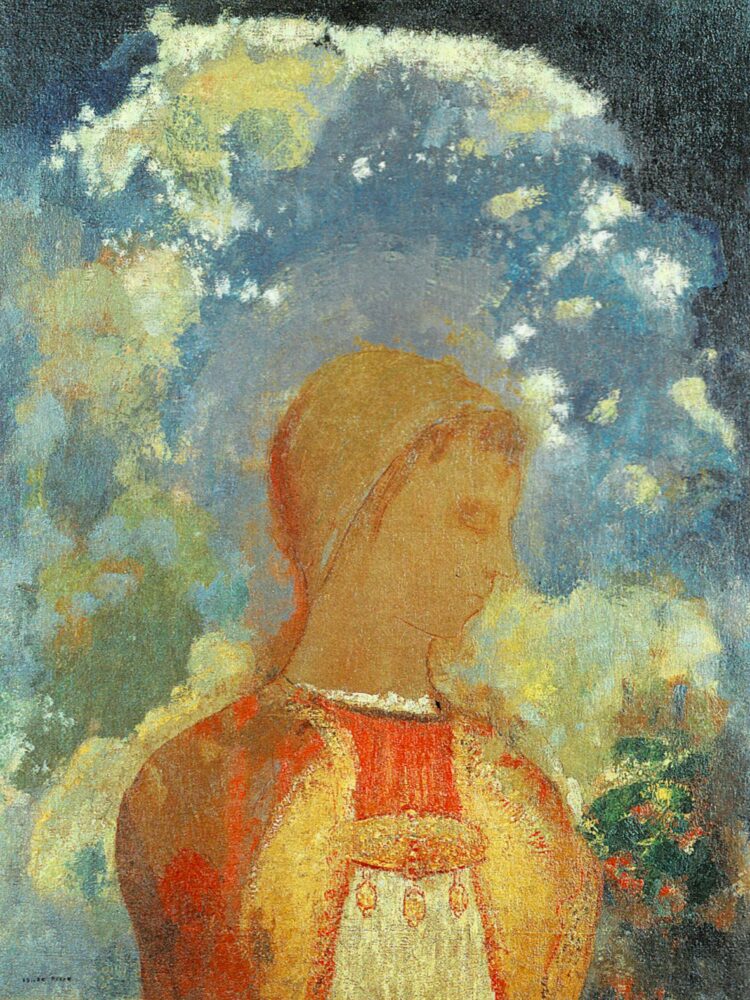

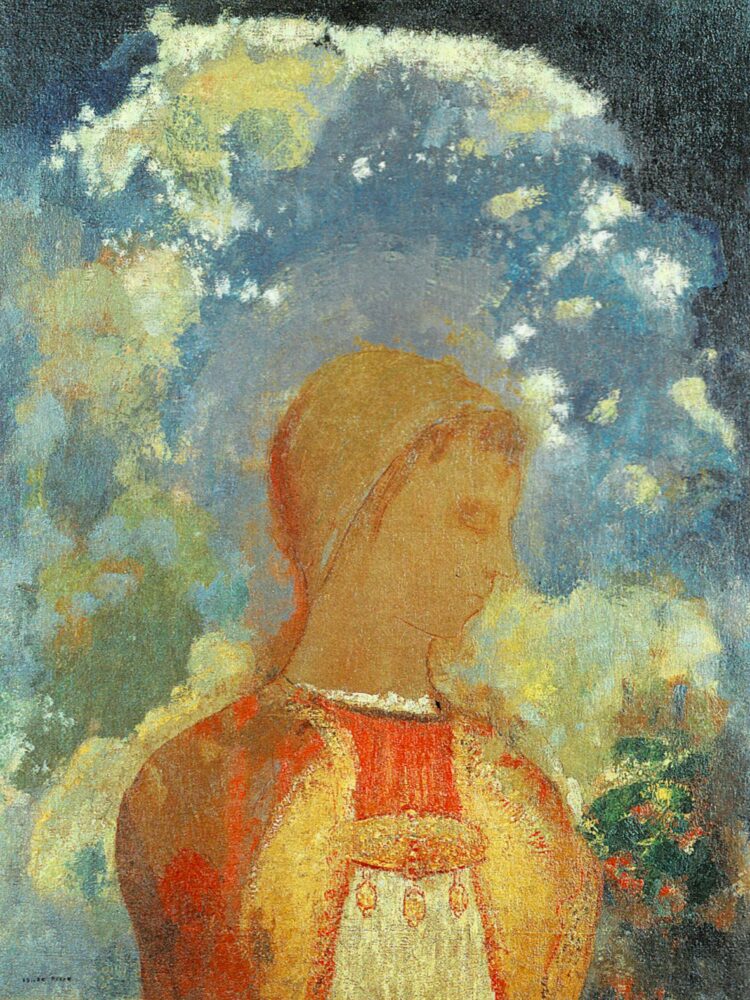

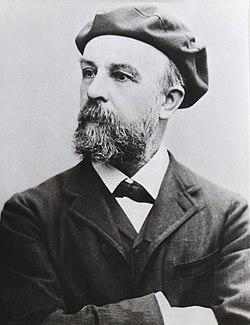

Odilon Redon

“Buddha in His Youth“ (1905)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

Redon’s Buddha — The Light of Imagination

Odilon Redon was one of the leading artists of French Symbolism.

Although he worked during the same period as the Impressionists, his focus was completely different.

Rather than painting the outer light of nature, Redon explored the inner light of the mind—dreams, imagination, and mystery expressed through color.

“Buddha in His Youth” beautifully captures this poetic vision.

Soft layers of color gently surround the young Buddha, creating a quiet, glowing presence.

While Redon is best known for his pastel works, this painting is done in oil.

Yet it still has the same delicate softness, with overlapping pigments that give the surface a deep, dreamlike texture—as if the image were floating between reality and imagination.

The Eastern Mystery in Redon’s Art

The subject, of course, is Buddha—the founder of Buddhism.

We don’t know exactly why Redon chose to depict him, but in late 19th-century Europe, there was a growing fascination with Asian culture, known as Japonisme.

Redon, like many other artists of his time, was inspired by Japanese art and Eastern philosophy, especially the spiritual calm and mystery of Buddhism.

The gentle radiance that fills this painting seems to symbolize Buddha’s inner light.

As you gaze at the figure, a sense of peace slowly takes over—inviting you to pause, breathe, and feel the quiet stillness within.

Auguste Renoir

“Mother and Child” (1916)

About This Work (Tap or Click to View)

One of Renoir’s Few Sculptures from His Later Years

Auguste Renoir, the Impressionist master known for painting people bathed in soft light, also created a few remarkable sculptures.

Did you know that “Mother and Child” is one of them?

This sculpture was made late in Renoir’s life and was inspired by his painting Motherhood (1885), which portrayed his beloved wife Aline.

“Motherhood” (1885)

A Collaboration Born from Love and Trust

By this time, Renoir was suffering from severe rheumatism and could barely hold a brush.

To bring his vision to life, the young sculptor Richard Guino assisted him, working closely under Renoir’s direction.

The result is a sculpture that seems to translate Renoir’s gentle brushstrokes into three dimensions — soft, warm, and full of tenderness.

More than technique, it reflects the deep trust and affection between the two artists.

Renoir passed away three years after this work was completed.

Mother and Child embodies his enduring love for his wife, his final creative passion, and the friendship that made it all possible.

It’s not only a beautiful sculpture — it’s a touching story of collaboration and devotion.

img: by Gervais Bougourd

Summary: “Seeing Art in Kyoto”

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto is not just a place to view famous masterpieces.

Here, you can experience the quiet presence of artists deeply connected to Kyoto and its unique culture.

The painters introduced in this article—Tomioka Tessai, Uemura Shoen, Yasui Sotaro, and Ohta Kijiro—were all born in Kyoto.

Each has a distinct style, yet you can feel a shared “Kyoto sensibility” in their works — whether in Shoen’s graceful gestures or the quiet spirituality in Tessai’s landscapes. These qualities are inseparable from the spirit of this ancient city.

Kishida Ryusei also lived in Kyoto for a time after the Great Kanto Earthquake.

During his stay, he became passionate about collecting antique art, which influenced his artistic concept of finding “beauty in the ordinary.”

Kyoto’s atmosphere and aesthetics played no small role in shaping his vision.

A masterpiece from his Reiko series, painted during his stay in Kyoto.

To look at a painting is to see the world through an artist’s eyes.

As you explore this museum, imagine how these painters observed Kyoto — a city with over a thousand years of history — and how they wove its essence into their art.

It’s a deeply rewarding way to experience both art and the spirit of Kyoto.

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto – Visitor Information

Location: 26-1 Enshoji-cho, Okazaki, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto Prefecture

Comments